Transcription

ImprovingFood Accessin CaliforniaReport to the California Legislature2012

Table of ContentsExecutive Summary . 2Food Access Advisory Group . 3Part 1: Food Access in California . 4Assembly Bill 581: The California Healthy Food Financing Initiative .4What is Food Access?.4The Problem of Limited Food Access: Under-consumption of Healthy Food in ManyCalifornia Communities.5Understanding Limited Food Access .7Available Resources to Improve Food Access .7Part 2: Recommendations for Improving Food Access . 11Distribution Barriers .11Distribution Recommendation: Support Regional Food Hubs .12Retail Barriers.16Retail Recommendation: Increase New Grocery Stores in Underserved Areas .17Retail Recommendation: Increase Healthy Food Sold at Existing Stores.20Barriers to Consumers .21Consumer Recommendation: Promote acceptance of EBT and WIC at farmers’ marketsand other food retailers .21Consumer Recommendation: Increase CalFresh Participation .23Consumer Recommendation: Support Farmers Market Nutrition Program Participation. 25Consumer Recommendation: Increase Healthy Food Incentive Programs .26Direct Distribution Recommendation: Support Healthy School Meals .27Direct Distribution Recommendation: Support Urban Agriculture .29Conclusion. 30Appendix 1: Federal Healthy Food Financing Initiative Grant & Loan Programs . 311

Executive SummaryCalifornia agriculture is incredibly productive and diverse. Whilefood from the state’s many ranchers and farmers is generallyeasily accessible, too many Californians do lack sufficient accessto healthy foods.To remedy this situation, in 2011 Governor Edmund G. Brown, Jr.signed AB 581, authored by Assembly Speaker John A. Pérez,which created the California Healthy Food Financing Initiative(CHFFI) to improve access to affordable, good-quality, healthyfood in communities that lack such access.CHFFI empowered the Secretary of the California Department ofFood and Agriculture to convene an advisory group to developrecommendations to be submitted to the Legislature on ways toincrease access to healthy foods. The recommendations in this report address how the infrastructure that movesfood from farmers to consumers disadvantages certain communities and propose strategies to reduce thosedisparities. The recommendations fit broadly into four categories and rely heavily upon resources and capabilitiesthat already exist here in California or are obtainable at the federal level: Improving the Distribution of Fresh ProduceExpanding Retail Options for Healthy FoodHelping Low-Income Consumers Purchase FoodSupporting Nutritious School MealsImproving the Distribution of Fresh ProduceThe report looks how food gets from farmers to retailers and consumers and recommends supporting regionalfood hubs, which can distribute healthy food to small stores and schools, as a way to provide fresh, Californiagrown produce to underserved communities. To help support regional food hubs California can facilitate access toexisting resources, including federal funding, for food hub development and to provide food hubs with technicalassistance such as using the information compiled by Occidental College on potential customers and producers anddirecting CDFA and the Department of General Services to explore opportunities at state fairgrounds.Expanding Retail Options for Healthy FoodThe report examines how California can encourage new and existing retailers to increase healthy food options inunderserved communities through a combination of facilitating access to existing federal and private resources aswell as philanthropic organizations, urging local governments to review regulations for new store development andcollaborate with organizations, such as the Healthy Corner Store Network, ending the moratorium on newCalifornia WIC vendors, and evaluating more frequent distribution of CalFresh benefits.Helping Low-Income Consumers Purchase FoodOnce healthy food becomes more available in underserved communities, many low-income consumers will stillstruggle to pay for it. To help increase consumers’ ability to pay for healthy food, California can make sure thatexisting nutrition assistance funds (primarily CalFresh and WIC) are accepted at all healthy food retailers bypromoting CalFresh acceptance in Certified Farmers’ Markets, allowing WIC Fruit and Vegetable Checks to beredeemed with a market manager (similar to CalFresh in farmers’ markets), and ensuring that the transition fromWIC to eWIC is compatible with all types of vendors.California can also increase low-income consumers’ access to nutrition assistance funds by removing barriers toCalFresh enrollment, increasing awareness of CalFresh and partnering with the Department of Health Care Servicesto reach out to CalFresh eligible Medi-Cal applicants. Federal funding should also be tapped for year-long incentiveprograms for CalFresh participants at Certified Farmers’ Markets.2

Supporting Nutritious School MealsChildren, many of whom often eat the majority of their food at school, benefit from healthier school meals. Stateagencies can increase food access for children by promoting healthy school meals through a statewide Farm-toFork office administered by CDFA and the use of federal funds to support implementation of Farm-to-Schoolprograms.Through an amazing combination of factors, including geography and geology, good weather and hard work,California is blessed with an abundance of nutritious, healthy food. The recommendations in this report,generated under the California Healthy Food Financing Initiative, creatively match existing resources withinnovative solutions, and can help ensure that all Californians have the opportunity to share in that bounty.Food Access Advisory GroupAB 581 Food Access Advisory GroupNameKeri Askew BaileyNoelle CremersPaula DanielsGail DelihantAnn EvansMichael FloodCornelius GallagherJohn HandleyJohn HewittGenoveva Islas-HookerMary KaemsJudi LarsenMary LeeJustin MalanSarah MercerAllen MoySantinia PasquiniDavid RunstenDavid ShabazianYelena ZeltserOrganizationCalifornia Grocers AssociationCalifornia Farm Bureau FederationLos Angeles Mayor’s OfficeWestern GrowersEvans and Brennan ConsultingLos Angeles Regional Food BankBank of AmericaCalifornia Independent Grocer AssociationGrocery Manufacturers AssociationCentral California Regional Obesity Prevention ProgramOffice of Assembly Speaker John PérezThe California EndowmentPolicyLinkCalifornia Conference of Directors of Environmental HealthCalifornia Pan-Ethnic Health NetworkPacific Coast Farmers’ Market AssociationRegional Council of Rural CountiesCommunity Alliance of Family FarmersSacramento Area Council of GovernmentsUrban & Environmental Policy Institute at Occidental College3

Part 1: Food Access in CaliforniaCDFA recognizes that the recommendations contained in thisreport do not enter a vacuum, but are the result of the tirelessefforts of many impassioned community members, businessleaders and policy makers. To better understand this context,the report begins with a brief history of the legislative contextand the national and statewide momentum that have providedthis opportunity. The report then defines food access and looksat the consequences of these limitations in many Californiacommunities. Next it describes the resources available withinCalifornia that can be used to increase food access forunderserved communities. These include resources from local,state, and federal government, including the federal nutrition programs that make up an important component offood access in underserved communities. Because California has limited new resources, the report emphasizesrecommendations that can be implemented with existing state, federal, and private resources.Assembly Bill 581: The California Healthy Food Financing InitiativeIn October 2011, Governor Brown signed Assembly Bill 581 (AB 581), the California Healthy Food FinancingInitiative. Authored by Assembly Speaker John A. Pérez, AB 581 creates the California Healthy Food FinancingFund, which consists of federal, state and private dollars to be used for increasing access to healthy foods inunderserved communities. The legislation also creates the California Healthy Food Financing Council, led by theTreasurer or his designee and includes the Secretary of Food and Agriculture or her designee, the Secretary ofHealth and Human Services or her designee, and the Secretary of Labor or his designee.AB 581 is modeled on the federal Healthy Food Financing Initiative. Announced in 2010, the federal Healthy FoodFinancing Initiative (HFFI) directs the federal departments of Agriculture, Health and Human Services, and Treasuryto make funds available through existing grant programs to specifically combat the problem of food access.AB 581 also directs the Secretary of Food and Agriculture to submit recommendations to increase food accessthroughout California. This report contains those recommendations, which are meant to serve as a roadmap forthe state as it seeks to increase food access.What is Food Access?Access to healthy food means having a variety of affordable, good quality, healthy food within one’s community.For the purposes of this report, healthy food will primarily refer to fresh fruits and vegetables, with frozen, dried,and canned vegetables as viable alternatives. Sufficient food access requires all of the following components:ProximityThe distance residents have to travel to reach outlets that sell healthy foods can impact the amount of healthyfood they purchase. Travel costs (including both the time spent traveling and the cost of driving a private vehicleor taking public transportation) can increase the real cost of healthy food and keep people from purchasing it.VarietyAccess to a variety of healthy food choices is another important part of food access. Variety ensures sufficientchoice – beyond a single option or two – and supports a healthy diet.QualityAccessible, healthy food should also be of good quality.AffordabilityAccessible food needs to be affordable. This includes both an affordable sticker price as well as the ability to usenutrition program benefits (e.g. CalFresh or WIC) in addition to cash.4

The Problem of Limited Food Access:Under-consumption of Healthy Food in Many California CommunitiesMany communities in California lack sufficient access to healthy foods. These underserved communities, oftenreferred to as “food deserts,” include poor inner-city neighborhoods and rural communities where residents live1far from the closest grocery store or supermarket. USDA defines this distance as greater than a mile for urbancommunities and as greater than 10 miles for rural communities. However, depending on the composition ofthese communities, the distance to a store could be shorter and still constitute a significant barrier (for example, ifa store is located across a physical barrier, such as a major highway or large hill, residents on the opposing sidemay not be considered to have access to that store).Residents of underserved communities musteither travel to purchase healthy food orpurchase less healthy food from closersources, such as convenience stores and fastfood restaurants. Time spent traveling toreach stores with healthier food selections canbe a prohibitive barrier, costing both timespent in transit as well as fees for publictransportation or gasoline. Shoppers usingpublic transportation are also limited in theamount of food they are able to carry withthem. Infrequency or unreliability of busservice can be an additional barrier thatincreases travel time and inconvenience.Shoppers who travel by car often purchase food in large quantities to save themselves the costs of future trips,which means purchasing fewer perishable items.Small corner stores and fast-food outlets are the only sources of food within these communities and often do notcarry much healthy food. Limited by their size and inability to achieve economies of scale, small stores, if they docarry healthy food, carry a limited variety that is more expensive and can be of a lower quality than what larger,full service grocery stores offer.The limited healthy food available within underserved communities and higher costs associated with travelinglonger distances to reach full service stores can keep people in underserved communities from purchasing healthyfood, or from purchasing healthy food in the quantity and frequency necessary for good health. This lack of foodaccess results not only in health disparities but also means that low-income communities pay more for food.Diet-related DiseaseResidents of underserved communities face disproportionately high rates of diet-related disease. Low-incomecommunities with few grocery stores and many fast-food and convenience stores have the highest rates of obesity2and diabetes in California. One study found that residents with no supermarkets near their homes were 25-463percent less likely to have a healthy diet (adjusted for age, sex, race, and socioeconomic indicators).1USDA defines food deserts as both low-income areas and ones in which more than a third of the population (at the censustract level) lives over a mile from a grocery store/supermarket (10 miles for rural ut.html2California Center for Public Health Advocacy, PolicyLink, and the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, Designed for Disease:The Link Between Local Food Environments and Obesity and Diabetes, 2008 available b43-406d-a6d5-eca3bbf35af0%7D/DESIGNEDFORDISEASE FINAL.PDF(Accessed April 2012).3Moore, L. et al, “Associations of the Local Food Environment with Diet Quality – A Comparison of Assessments Based onSurveys and Geographic Information Systems: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis,” American Journal of Epidemiology167 (2008): 917–924. (Available online at: ll.pdf html (Accessed April 2012)5

Conversely, access to healthy food is correlated with positive healthoutcomes. The presence of supermarkets has been associated with4lower rates of obesity. One study found that African-Americans living incommunities with at least one supermarket were more likely to meetfruit and vegetable consumption guidelines than those living in5communities without supermarkets.Moreover, the inability to pay for healthy food is associated withobesity. According to the Food Research and Action center “householdswithout money to buy enough food often have to rely on cheaper, highcalorie foods to cope with limited money for food and stave off hunger. Families try to maximize caloric intake for6each dollar spent, which can lead to over consumption of calories and a less healthful diet.”The impact of this problem is magnified when the costs associated with treatment are considered. Medical costsof obesity in California are estimated to be above 7 billion, including more than 1.7 billion in Medicare and 1.77billion in Medi-Cal costs alone. Additional costs of obesity include many indirect costs as well, includingdecreased productivity and missed work and school days.Although increasing food access alone will not solve the obesity crisis, increasing access to healthy food is animportant part of the solution. Increased access can make the healthy choice the easy choice and support otherefforts to reduce obesity.Which California communities are most affected by limited food access?Although under-consumption of healthy food is a problem across California and the nation, it has a more strikingimpact on certain communities:Low-interest Communities and Communities of ColorUnderserved communities are predominately low-income communities of color. In California, low-income8communities have 20 percent fewer sources of healthy food when compared with higher-income communities.Nationally, low-income communities have 25 percent fewer chain supermarkets than middle-income9communities. Compared with predominately white neighborhoods, black neighborhoods have only 52 percent asmany chain supermarkets; Latino neighborhoods have only 32 percent as many chain supermarkets as non-Latino10neighborhoods. Although some neighborhoods have independent grocery stores, many low-income communitiesare not served by any type of grocery store and must rely on fast-food outlets and convenience stores.4Morland K, et al. “Supermarkets, other food stores, and obesity: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study.”Am J Prev Med. Apr 2006;30(4):333-339.5Zenk, S. et al., “Fruit and Vegetable Intake in African Americans Income and Store Characteristics,” AmericanJournal of Preventive Medicine 20:1 (2005).6Food and Research Action Center. “Hunger in the U.S.” Last updated November, 2009. Available online athttp://www.frac.org/html/hunger in the us/hunger index.html71998-200 estimates. See: Runge, C.F., “Economic Consequences of the Obese,” Perspectives in Diabetes, Vol 56, November2007, 2668-2672.8California Center for Public Health Advocacy, PolicyLink, and the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research,Designed for Disease: The Link Between Local Food Environments and Obesity and Diabetes, 2008 available b43-406d-a6d5-eca3bbf35af0%7D/DESIGNEDFORDISEASE FINAL.PDF(Accessed April 2012).9Powell, L. et al., “Food Store Availability and Neighborhood Characteristics in the United States,” American Journal ofPreventive Medicine 44 (2007): 189–195.10Powell, L. et al., “Food Store Availability and Neighborhood Characteristics in the United States,” American Journal ofPreventive Medicine 44 (2007): 189–195.6

Inner CitiesMany inner city communities have limited food access. Food choices in these communities are often limited tofast food outlets and the offerings of small corner stores, which often do not stock perishable produce. Thehealthy food that is available within inner cities often costs more than food purchased elsewhere, because it is sold11through smaller stores, which tend to charge about 10 percent more than supermarkets.Rural CommunitiesResidents of rural areas often live miles from the nearest grocery store. Nationally, rural areas have 14 percent12fewer chain supermarkets than urban areas. As rural populations have decreased (as more residents movecloser to urban areas), the number of grocery stores in rural areas has also decreased, leaving remaining residentswith fewer stores to purchase food from and long distances to reach them.Understanding Limited Food AccessThe aforementioned disparities are not the result of deliberate design, but are, rather, the result of the evolutionof our food system. Understanding this evolution and the root causes of these disparities are essential toimplementing policy solutions that can actually create real change.Healthy food begins with growers and is then distributed to retailers and other entities providing food (such asschools and food banks) to the consumer. In underserved communities, one or multiple parts of this system donot function well, resulting in an under-provision of healthy ia farmers grow healthy food in abundance. The system begins tounderperform for underserved communities starting with the distribution ofhealthy food because certain buyers, such as schools and small stores, canface difficulties purchasing healthy food in sufficient quantity. Underservedcommunities also face a shortage of retail outlets where they can purchase avariety of healthy food. And, lastly, many consumers in underserved areasare not able to afford sufficient quantities of healthy food.To address the issue of food access – and bring a variety of affordable,quality healthy food nearby to residents of underserved communities – weneed to address these multiple points in the process of getting healthy foodto underserved communities. The recommendations in this report focus onthese three issues – distribution, retail outlets, and consumers’ ability to pay.These recommendations support one another and the successfulimplementation of one will promote the success of others.Available Resources to Improve Food AccessCalifornia currently has access to many resources that can be used toimplement these recommendations and increase food access. To increasefood access, the state can more effectively coordinate existing state andfederal resources to target them toward use in underserved communities.11Kaufman, P. et al., “Do the Poor Pay More for Food? Item Selection and Price Differences Affect Low-Income Household FoodCosts.” U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Economics Report No. 759; November, 1997.12Powell, L. et al., “Food Store Availability and Neighborhood Characteristics in the United States,” American Journal ofPreventive Medicine 44 (2007): 189–195.7

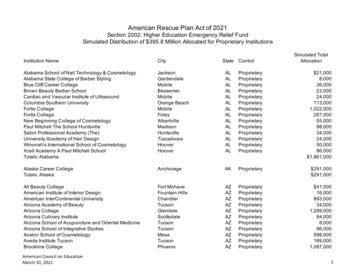

State ResourcesCalifornia will likely be unable to devote new funds toward increasing food access in the near future. However,there are existing state resources that can, if used in a more targeted way, increase food access. For example, thestate owns county fairgrounds, which often include cold storage and commercial kitchen facilities. Coordinationbetween different state agencies can avoid duplication and more efficiently coordinate state programs andresources to increase food access.Federal ResourcesCalifornia should maximize the use of existing federal funding. There are approximately 420 million availablefederal dollars through the federal Healthy Food Financing Initiative. Federal funds also support additionalprograms – such as CalFresh – that can be used to increase food access. (See the next section on federal nutritionprograms for how these programs support food access.)Community Partners: Businesses, Non-profits, Foundations, and FarmersThere are also numerous non-governmental resources available to address limited food access. These includebusinesses, non-profits, foundations, and farmers. Stores and food hubs can be sources of healthy food inunderserved communities and integral to innovative approaches to increasing healthy food access in underservedcommunities. Many non-profits have expertise in food access issues and can provide effective models andtechnical assistance and community-based organizations have relationships with residents in underservedcommunities and can ensure that communities are involved in decisions and implementation of solutions. Manyfoundations and community development financial institutions are also active in efforts to increase food accessand can provide funding for solutions across the state. Many farmers, in addition to growing healthy food, alsoparticipate in programs to increase access, such as the Farm-to-Family program.Coordinating EffortsGovernment and private efforts to increase food access are already underway at the federal, state, and local levels.In order to harmonize these efforts and avoid duplication, the state can take an active role in coordinating effortsand sharing information among the various entities working to increase food access. CHFFI can serve to facilitatethis coordination and make sure communities have partners at the table and that they are connected to theappropriate funding sources.Existing Resources: Background on Federal NutritionAssistance ProgramsMany residents of underserved communities are currently participating in, orare eligible to participate in, federal nutrition assistance programs. Althoughdramatically underutilized, these programs play an important role and have thepotential to further increase food access.Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program/CalFreshThe Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as theFood Stamp Program, provides participants with monthly benefits to be usedfor food purchases. In California, SNAP is called CalFresh. To be eligible forCalFresh, participants can have a maximum gross income of 130 percent of theFederal Poverty Level, with a net income of 100 percent FPL. Able-bodiedadults (ages 18 – 49) without dependents must meet work requirements (20hours/week of work or work activity/workfare) in order to receive CalFresh13benefits for more than three months in a 36-month period.13For detailed eligibility requirements, see California Department of Social Services, CalFresh Eligibility and IssuanceRequirements at http://www.calfresh.ca.gov/PG841.htm (Accessed April 2012)8

About 3.67 million low-income Californians14participated in CalFresh during 2011, which was only53 percent of the eligible population. Children accountfor 60 percent of CalFresh participants. CalFresh is anentitlement program, which means that all eligibleapplicants have a right to receive benefits.In 2011, the average monthly CalFresh benefit was15 147 per person. Electronic Benefits Transfer Cards(EBT cards) are used to distribute CalFresh benefits, inaddition to other benefits such as CalWORKS. CalFreshbenefits can be used to purchase food at authorized retailers. CalFresh benefits cannot be used to purchasealcohol, tobacco, foods meant to be eaten in the store, vitamins, and household items.Special Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)16WIC provides nutrition assistance to low-income pregnant, postpartum and breastfeeding women, infants andchildren under the age of five. WIC participants receive monthly paper coupons to purchase specific foods fromWIC food packages designed to provide nutrients necessary to healthy development, including Vitamins A and C,protein, calcium, and iron. WIC food packages include milk, cheese, eggs, cereal, juice, dry beans, peanut butter,infant formula, fresh fruits and vegetables, and whole grains. WIC checks can be redeemed statewide at over175,100 authorized stores, including some WIC-only stores. In additional to access to healthy foods, WIC alsoprovides nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and other services.18In 2010, the average benefit in California was 47 per month. That year, approximately 1.5 million Californiansparticipated in WIC: 23 percent were pregnant or postpartum women, 20 percent infants 0-11 months old and 5719percent children between 1 and 5 years of ages. Over 60 percent of Californian infants born in 2010 were20enrolled in WIC.Unlike SNAP, WIC is not an entitlement program. If there is not enough funding available to cover all eligible21applicants, local WIC agencies determine which eligible applicants will receive benefits.National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast ProgramThe National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and School Breakfast Program (SBP) provide daily meals toschoolchildren. Schools provide over 4.4 million meals to California children – many of them from underserved22communities – every day. For many children, school meals are their primary source of food. Because school14Food and Nutrition Services, USDA. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Average Monthly Participation, available at:http://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/15SNAPpartPP.htm (Accessed April 2012)15Food and Nutrition Services, USDA. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Average Monthly Benefit per person,available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/18SNAPavg PP.htm (Accessed April 2012)16“Low-income” is defined as at or below 185 percent of the Federal Poverty Level.17California WIC Program at a Glance, February 2012, available nts/WICProgramAaGlance.pdf (Accessed April 2012)18USDA Food & Nutrition Service, WIC Program: Average Monthly Benefit per Personhttp://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/25wifyavgfd .htm (Accessed April 2012)19California WIC Program at a Glance, February 2012, available nts/WICProgramAaGlance.pdf (Accessed April 2012)20California WIC Program at a Glance, February 2012, available nts/WICProgramAaGlance.pdf (Accessed April 2012)21For more information on the prioritization of WIC applicants, please lityprioritysystem.htm. (Accessed April 2012)22Nutrition Services Division, California Department of Education: Annual Child Nutrition Programs Participation Data. Availableat: htt

Access to healthy food means having a variety of affordable, good quality, healthy food within one’s community. For the purposes of this report, healthy food will primarily refer to fresh fruits and vegetables, with frozen, dried, and canned vegetables as viable alternatives. Sufficient food