Transcription

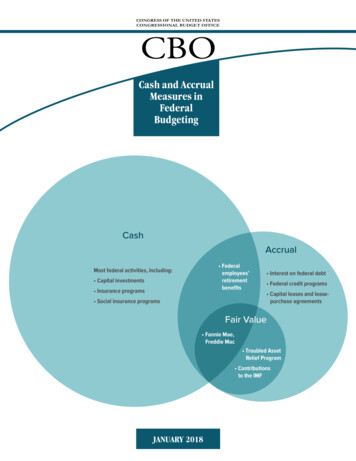

CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATESCONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICECash and AccrualMeasures inFederalBudgetingCashAccrual Federalemployees’retirementbenefitsMost federal activities, including: Capital investments Insurance programs Social insurance programs Interest on federal debt Federal credit programs Capital leases and leasepurchase agreementsFair Value Fannie Mae,Freddie Mac Troubled AssetRelief Program Contributionsto the IMFJanuary 2018

www.cbo.gov/publication/53461

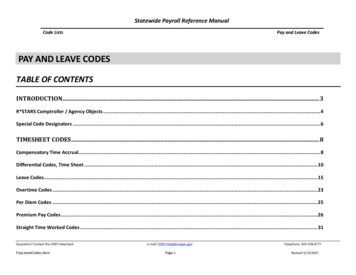

ContentsSummaryWhat Roles Do Cash and Accrual Measures Play in the Federal Budget Process?What Are the Advantages and Disadvantages of Cash and Accrual Measures?What Are the Criteria for Assessing Information Provided by Cash and Accrual Measures?What Are Potential Approaches for Selectively Expanding the Use of Accrualand Other Long-Term Measures in the Federal Budget Process?1122Overview of the Federal Budget Process34BOX 1. THE FEDERAL BUDGET PROCESS AND BUDGET ENFORCEMENT PROCEDURES2An Illustration of Cash Versus Accrual Measures5The Role of Cash and Accrual Measures in the Federal Budget ProcessAccrual-Based Budgetary Treatment66BOX 2. ILLUSTRATING ALTERNATIVE BUDGETARY TREATMENTS: ESTIMATING THESAVINGS FROM LIMITING FORGIVENESS OF GRADUATE STUDENT LOANSBOX 3. ACCOUNTING FOR MARKET RISK IN ACCRUAL-BASED ESTIMATESOther Measures Used in the Federal Budget ProcessAdvantages and Disadvantages of Cash and Accrual MeasuresBOX 4. INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCE WITH ACCRUAL BUDGETING: WHAT ARE THE LESSONS?1014161820Expanding the Use of Accrual Measures in the Federal Budget and Budget ProcessCriteria for Assessing Information Provided by Cash and Accrual MeasuresApproaches to Expanding the Use of Accrual and Other Long-TermMeasures in the Federal Budget Process2222About This Document29Tables1.2.3.4.26Estimates of the Costs of Legislation Authorizing IllustrativeSettlements Using Alternative Measures7Accrual and Long-Term Measures Used in the Federal Budget Process9Comparing Cash and Accrual Measures of Costs19Assessing 10-Year Cash and Accrual Measures of Selected Noncredit Federal Programs 23Figures1. Current Budgetary Treatment for Selected Federal Programs2. The Budgetary Treatment of Federal Credit Programs With Positive Subsidy Costs812

Cash and Accrual Measuresin Federal BudgetingSummaryThe federal budget serves many important functions,including tracking the government’s cash flows, serving as a key instrument in national policymaking,summarizing how fiscal policy changes over time, andcommunicating the nature and scope of governmentalactivities. The net costs of federal activities are estimatedthroughout the federal budget using two fundamentallydifferent accounting measures—cash accounting andaccrual accounting. The principal difference betweencash and accrual accounting lies in the timing of whenthe commitment (or collection) of budgetary resourcesis recognized. Transactions in cash-based accounting arerecorded when payments are actually made or receiptscollected. By contrast, accrual measures summarize in asingle number the anticipated net financial effects at aspecific point in time of a commitment that will affectfederal cash flows many years into the future. That is,accrual methods record the estimated value of expensesand related receipts when the legal obligation is firstmade rather than when subsequent cash transactionsoccur. Currently, most federal activities are recorded inthe budget on a cash basis, with the major exception offederal credit programs, which are recorded on an accrualbasis.Whether programs are accounted for on a cash or anaccrual basis can, in some cases, significantly affect thesize and timing of their estimated deficit effects. Cashbased estimates used in the budgeting process generally reflect costs over the 10-year period on which theprocess focuses, but that period may not be long enoughto capture the full extent of some activities’ effects.Accrual-based estimates that consider long-term effectsprovide more complete information about programs thatinvolve longer time frames. Such estimates could givelawmakers a tool to use in setting and enforcing targetsfor long-term deficit control because, for the purposes ofCongressional budget enforcement procedures, legislativeproposals would receive credit (or be charged) withinthe 10-year budget horizon for the ultimate effects ofprovisions that would save (or cost) money over a longerperiod. For example, accrual estimates might provideuseful information about the net costs of changes infederal retirement benefits and in a limited number offederal insurance programs. In addition, some analystsbelieve accrual-based estimates would provide particularly useful information about certain social insuranceprograms because of their long time frames and themagnitude of cash flows involved.This report discusses the relative merits of cash andaccrual measures and explores the implications ofexpanding the use of accrual measures for decisionmaking purposes. In subsequent reports, the CongressionalBudget Office will examine in greater detail how anaccrual treatment would differ from the current cashtreatment for specific types of programs.What Roles Do Cash and Accrual Measures Play in theFederal Budget Process?Measures of budgetary effects inform policymakers’decisions about how to allocate limited federal resources.Lawmakers rely on estimates of such effects to determinehow legislative proposals would affect the federal deficitand whether they would trigger statutory or legislative“budget enforcement” procedures that are designed tocontrol revenues, spending, and deficits.The federal budget currently reports the costs of nearlyall commitments on a cash basis. The rationale for thatapproach is that cash measures are simple, understandable, and can be used to reliably estimate most programs’fiscal effects. However, the costs of some commitmentswith long-term budgetary effects are reported on anaccrual basis. For instance, the Federal Credit ReformAct of 1990 (FCRA) requires federal direct loans andloan guarantees—for which cash flows typically extendwell beyond the 10-year budget horizon—to be recordedin the budget on an accrual rather than a cash basis. Forsuch programs, the budget records a single payment orreceipt that represents the net present value of expected

2 Cash and Accrual Measures in Federal Budgetingfuture cash flows. Policymakers made the switch to moreaccurately measure the full net cost of credit programsover the long term and to facilitate comparisons of thenet cost of direct loans, loan guarantees, and grants. Inaddition, certain transactions related to federal retirement benefits are reported on an accrual basis in agencies’ budgets (in order to measure some of the long-termcosts of current employees), but the overall budget totalsreflect current-year cash flows—the government’s payments to annuitants and employees’ contributions to theretirement funds.What Are the Advantages and Disadvantages of Cashand Accrual Measures?Cash and accrual measures have competing advantagesand disadvantages in the budget: Cash measures are transparent, verifiable, and trackchanges in debt held by the public. They also workwell for programs with short timing lags. However, the cash measures used in the federalbudget process may provide incomplete informationabout some programs that involve futurecommitments because the 10-year window truncatesthe budgetary effects. For example, cash measuresfail to show the liability that taxpayers incur in agiven year for federal employees’ accrued retirementbenefits and the long-term costs or savings that wouldresult from changes in those benefits. In such cases,cash projections that extend farther into the futurecan highlight long-term trends, even if they are notan integral part of the budget process. In combination with truncated time horizons, cashaccounting introduces opportunities for policymakersto adjust budgetary outcomes through timingshifts—that is, by instituting nonsubstantive policiesthat simply delay payments or accelerate receiptswithout materially changing their underlying value. Accrual measures succinctly convey whether policychanges are expected to increase or decrease the deficitover the long term, thereby facilitating comparisonsof the net cost of programs with cash flows that differin timing (or exposure to market risk) and potentiallyimproving lawmakers’ opportunity to control longterm costs when commitments are initially made.11. Market risk is a component of financial risk that remainseven with a well-diversified portfolio and is correlated withmacroeconomic conditions.January 2018 Accrual estimates, however, are methodologicallycomplex, sensitive to technical assumptions, subjectto the uncertainties of projecting program activityfar into the future, and therefore more volatile andharder to explain and understand than cash measures. Increasing the use of accrual measures in the budgetwould require new account structures and reestimatesto reconcile present-value estimates with actual cashflows.What Are the Criteria for Assessing InformationProvided by Cash and Accrual Measures?CBO has identified three criteria to assess the trade-offsbetween the 10-year cash measures now used in thefederal budget process and accrual measures that reflectbudgetary effects over longer periods: Do the measures convey complete information aboutbudgetary effects? That is, do they correctly indicatewhether programs have net costs or savings andprovide a reasonable sense of the magnitude of sucheffects? Is the government’s commitment of future resourcesfirm enough to record future cash flows before theyoccur? Budget projections generally reflect anticipatedcash flows stemming from future commitments aslong as they are probable under current laws andpolicies; but the case for accrual measures may bestronger for commitments that are legally bindingor otherwise firm and that require no furtherCongressional action to ensure that agencies havesufficient resources to pay for them. Can underlying long-term cash flows be projectedand discounted with sufficient accuracy so thataccrual measures can be reliably used in the budgetprocess?What Are Potential Approaches for SelectivelyExpanding the Use of Accrual and Other Long-TermMeasures in the Federal Budget Process?For programs where accrual measures are judged to beuseful, the Congress could require such measures for allaspects of budgetary treatment and accounting; expandthe use of accrual measures only for the Congressionalbudget process; or use those measures as supplementalinformation.

January 2018 Requiring accrual-based budgetary treatment andaccounting, as was done for federal credit programs,would change measures of how programs affectthe budget deficit and would require new accountstructures and periodic revisions to estimates. Becausethe basis of measurement would be consistentthroughout the federal budget process, lawmakerswould have a reasonable idea of how their decisionsabout resource allocation would ultimately affectthe Administration’s execution of statutory budgetenforcement mechanisms. Using accrual estimates only for purposes ofCongressional budget enforcement would changelegislative cost estimates and might affect decisionsabout the allocation of resources. That approachwould be less burdensome than reporting accrualestimates in the budget, which would remain cashbased. However, because the allocation of resourcesacross federal programs might ultimately dependon how the Administration executes statutoryrequirements related to budget enforcement, usingdifferent measures for Congressional and statutorybudget enforcement could cause confusion. Using accrual estimates as supplemental informationwould allow policymakers to judge their valuewithout changing the budget numbers or budgetenforcement procedures.Overview of the Federal Budget ProcessThe federal budget is a measure of the overall scope andmagnitude of federal activities that involve the spendingor collection of money under existing laws. It is also theprimary tool that lawmakers use to allocate the government’s resources among competing priorities and to promote economic growth and prosperity. The 1967 Reportof the President’s Commission on Budget Concepts concluded that, in addition to its role in national policymaking, the budget must be understandable to the public, aswell as to lawmakers.2 It should convey the overall size ofgovernment relative to the economy, as well as the relative size of different government programs. Estimates ofbudget totals should be useful for analyzing the impactof federal spending and tax revenues on the economy,2. See President’s Commission on Budget Concepts, Report of thePresident’s Commission on Budget Concepts (October 1967),pp. 11–23, http://tinyurl.com/y7lxv3gp.Cash and Accrual Measures in Federal Budgetinginforming the government’s borrowing needs, and measuring the public debt.The federal budget process is the mix of procedures thatthe President and the Congress use to consider, enact,and execute the laws that allocate those resources. Thatprocess is governed by various rules and procedures formeeting budgetary goals through the use of enforcementmechanisms that aim to control revenues, spending,and deficits on the basis of estimates prepared by boththe Congressional Budget Office and the Office ofManagement and Budget (OMB).3Most estimates of how federal activities would affect thefederal deficit reflect cash-based measures of costs overa 10-year period. That period begins with the budgetyear—the upcoming fiscal year for which the Congressmust enact new legislation to allow federal agencies tocontinue operating—and spans nine subsequent years.However, the costs of some federal commitments withlong-term budgetary effects—in particular, the government’s credit programs—are recorded in the budget (andin legislative cost estimates) on an accrual basis, showing net budgetary effects when commitments are maderather than when subsequent cash transactions occur.To aid in Congressional deliberations, CBO prepares10-year projections of federal cash flows and the resulting federal deficit. For the most part, CBO’s budgetprojections incorporate the assumption that current lawsgoverning taxes and spending in future years remainin place. CBO’s estimates of the budgetary effects ofproposed legislation are estimated relative to thoseprojections.4Whereas CBO provides estimates for use duringCongressional deliberations, OMB’s estimates are incorporated in the President’s budget proposals and are usedin implementing certain statutory requirements. Forexample, if newly enacted laws are estimated to causecertain limits to be breached, OMB must cancel3. The Office of Management and Budget in the executive branch—referred to in this report as the Administration—is responsible forprojecting cash flows related to enacted legislation in the federalbudget. Its budgetary treatment of activities may differ from thetreatment CBO uses in its cost estimates.4. The Joint Committee on Taxation is a nonpartisan Congressionalcommittee that assists Members with tax legislation. The staffof the Joint Committee on Taxation, not CBO, estimates therevenue effects of tax proposals.3

4 Cash and Accrual Measures in Federal BudgetingJanuary 2018Box 1 .The Federal Budget Process and Budget Enforcement ProceduresThe federal budget process is an amalgam of procedures,developed over time, that policymakers in the legislative andexecutive branches use to plan, establish, control, and accountfor spending and revenue policies. It involves three mainphases: the formulation of the President’s budget proposals bythe executive branch, the Congressional process for budgetarydecisionmaking, and the execution of enacted budget-relatedlegislation. The process is governed by various rules andprocedures for meeting budgetary goals and enforcementmechanisms that aim to control revenues, spending, anddeficits on the basis of estimates prepared by both theCongressional Budget Office and the Office of Managementand Budget (OMB). Those enforcement mechanisms—as wellas estimates of budgetary effects used to execute them—recognize the fundamental distinction between the threeprimary components of the federal budget: Discretionary spending—spending stemming from authorityprovided in annual appropriation acts; Mandatory (or direct) spending—spending controlled bylaws other than appropriation acts; and Revenues—tax receipts and other collections stemmingfrom the federal government’s use of sovereign power.Formulation of the President’s BudgetOMB generally handles the formulation of the President’sbudget, on the basis of proposals and estimates provided byother agencies. That budget is essentially a request to theCongress to enact new legislation as necessary to implementthe Administration’s policies regarding spending and revenues. The budget recommends overall levels of spending andrevenues for the coming fiscal year (the “budget year”) and,usually, nine subsequent years; specifies how resources shouldbe allocated among federal activities; and, in some cases,proposes changes to laws aimed at achieving those budgetarygoals. It also includes detailed information about spendingand revenues in the current year and the prior year. No budgetenforcement procedures apply to the President’s request. OMBusually transmits the budget to the Congress in February.The Congressional Budget ProcessThe Congressional budget process provides the means forlawmakers to establish their own fiscal and budgetary goalsand ensure that new legislation would comply with thosegoals. As envisioned in the Congressional Budget Act of 1974,Congressional consideration of budgetary issues centers ona budget resolution, which, like the President’s budget, setsforth an overall budget plan for the upcoming budget year (andusually nine subsequent years) and allocates resources amongfederal activities.1 The budget resolution is enforced in eachHouse of Congress—usually on the basis of estimates preparedby CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation—through procedural mechanisms that are set forth in law and in the rulesof each House.2 Lawmakers use two principal mechanismsto ensure that proposed legislation complies with budgetarygoals specified in a budget resolution: Points of order—parliamentary objections that lawmakerscan raise against proposed legislation that would violatecertain Congressional rules, particularly pay-as-you-gorules (described below) that prohibit the consideration oflegislation estimated to have certain budgetary effects. Reconciliation—a parliamentary process that the Congress sometimes uses to reconcile spending and revenueamounts determined by legislation for a given fiscal yearwith amounts set in the budget resolution. When used, thatprocess is triggered by reconciliation instructions in thebudget resolution, which direct Congressional committeesto propose changes in laws under their jurisdictions toachieve a specified budgetary result. Special rules governCongressional consideration of reconciliation legislation.Budget ExecutionOMB generally handles budget execution—that is, OMB apportions the budgetary resources to executive branch agencies.The budget execution process also involves periodic executionreports by agencies, the recording of actual spending in thebudget, preparation of accrual-based financial statements,and audits to verify that such financial statements track withunderlying cash flows. OMB also determines, usually on thebasis of its own estimates, whether new legislation enacted fora given fiscal year, in total, triggers statutorily prescribed mechanisms for budget enforcement and, if necessary, executes1. Congressional resolutions are not presented to the President and do nothave the force of law. In some years, the full Congress adopts a concurrentbudget resolution that governs budget enforcement in both the House andthe Senate. In other years, the chambers adopt separate resolutions or noneat all.2. See Congressional Budget Office, “Frequently Asked Questions About CBOCost Estimates,” www.cbo.gov/about/products/ce-faq.

January 2018Cash and Accrual Measures in Federal BudgetingBox 1.ContinuedThe Federal Budget Process and Budget Enforcement Proceduressuch mechanisms. Statutory mechanisms for controlling discretionary spending differ from those used to control mandatoryspending and revenues.Discretionary spending is limited by caps on new discretionaryappropriations that were originally specified in the BudgetControl Act of 2011 (BCA) and modified by subsequent legislation. Under current law, separate caps exist for defense andnondefense spending through 2021. If OMB determines thatthe total amount of discretionary funding provided in appropriation acts for a given year exceeds the cap for either category,the President must cancel new budgetary authority (followingprocedures specified in the BCA) to eliminate the breach.Mandatory spending and changes to revenues are controlledthrough two enforcement mechanisms. First, pay-as-you-go(PAYGO) procedures (specified in the Statutory Pay-As-You-GoAct of 2010) require new legislation enacted during a givensession of Congress with effects on mandatory spending orrevenues to be deficit-neutral over specified periods of time.In other words, policy changes that would increase directspending or reduce revenues must be offset by other changesthat would reduce other direct spending or increase revenues.some new funding following statutorily specified procedures (a process called sequestration). To guard againsttriggering such reductions, lawmakers use certainprocedures—outlined both in law and in rules thatgovern parliamentary procedures—to ensure thatproposed legislation complies with budgetary goalsestablished by the Congress (see Box 1).An Illustration of Cash Versus AccrualMeasuresThe choice of whether to use cash or accrual measuresas the basis for decisions about how to allocate resourcesaffects both how costs are reported to the Congress andthe public and how policymakers apply budget enforcement mechanisms. The basis used to estimate the sizeand timing of programs’ budgetary effects has significant implications for how policymakers apply thosemechanisms.Cash and accrual measures differ when there are substantial lags between the time when budgetary commitmentsare made and the resulting cash flows occur. Whereastransactions in cash-based accounting are recorded(Introducing more accrual estimates to the budget would affectthe size of the changes and give policymakers an incentiveto pursue policies that would reduce costs far into the futureto offset near-term increases in other spending or reductionsin taxes.) That statutory PAYGO requirement applies not toindividual pieces of legislation but rather to the cumulative neteffect of all new laws enacted during a Congressional session.If, at the end of a session, OMB estimates that newly enactedlegislation would violate that requirement, the President mustorder a sequestration—or across-the-board cut—of certainmandatory spending programs to offset the net cost of the newlaws. In addition, under current law, automatic sequestrationsof mandatory spending are scheduled to occur each fiscal yearover the 2018–2025 period.33. Those automatic reductions were originally prescribed by the BCA, whichestablished the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction to proposelegislation to reduce federal deficits by a total of 1.2 trillion over a 10-yearperiod. The BCA specified that unless lawmakers enacted legislation thatachieved such savings, the automatic reductions would occur, withoutfurther legislation, through 2021. Those automatic reductions have sincebeen extended into later years by subsequent legislation, most recently theBipartisan Budget Act of 2015.when payments are made or receipts collected, accrualestimates translate expected future cash flows into apresent value that is comparable to a single equivalentamount at one point in time. Net present-value estimatesadjust future payments (or income) for the time value ofmoney—specifically, by discounting the value of futurecash flows. Discounting recognizes that a dollar in thefuture is worth less than a dollar today because of theinterest that could have been earned on that dollar inthe meantime. Analysts begin by projecting the streamof cash flows they expect will result from a particularactivity. To the extent practicable, such projections coverthe entire period over which such effects are expected tooccur. Analysts can then calculate the present value ofthat stream of cash flows by discounting each amountto current dollars and summing the resulting series. Thehigher the discount rate, the lower the present value offuture cash flows. As a result, present-value calculationsand other accrual measures depend on estimates of bothcash flows and discount rates.To illustrate the differences between the two approaches,suppose that lawmakers are considering legislation that5

6Cash and Accrual Measures in Federal Budgetingwould authorize a settlement under which the federalgovernment agreed to make payments to the affectedparties equaling 3 million annually for 10 years. Acash-based estimate would project outlays of 3 millionannually—or 30 million over the 10-year budgetwindow—equal to the nominal amount paid to theparties over the 10-year period (see Table 1). By contrast,on an accrual basis, the cost estimate would report,up front in the year the commitment was made, apresent-value estimate equal to the discounted value ofthe annual payments to be made in future years. At a discount rate of 2 percent, the present value of payments tothe parties would total 26.9 million. Accrual estimatesmust ultimately be reconciled with the actual cash flows,which would still need to be tracked.5In the context of the 10-year federal budget horizon,projections of budgetary effects under cash and accrualmeasures diverge for activities in cases where budgetaryeffects are expected to continue in later years. For suchactivities, if a cash measure is used, the 10-year budgetwindow truncates the effects. The greater the magnitudeof budgetary effects projected beyond the first 10 years,the greater the divergence. For example, suppose insteadthat the settlement entered into by the governmentwould require payments to continue for 20 years. Acash-based estimate of costs used for the Congressionalbudget process would remain unchanged at 30 millionover 10 years (though CBO’s estimate would disclose,as supplemental information, additional spending of 30 million outside the projection period). By contrast,at a discount rate of 2 percent, an accrual-based costestimate would account for all of the projected spendingup front, reporting 49.1 million as the present value offederal commitments entered into in the first year of thesettlement.The Role of Cash and Accrual Measures inthe Federal Budget ProcessWith very few exceptions, the federal budget reports thecosts of its commitments on a cash basis. That budgetarytreatment applies to the government’s largest programs—including Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid—andthe bulk of defense and nondefense spending that is governed by the annual appropriation process (see Figure 1).5. In this case, the Treasury would pay 2 percent interestannually on the undistributed sums, which would be held innonbudgetary accounts, and those interest outlays together withthe original present-value amount would bring total outlays to 30 million over 10 years.January 2018However, the costs of some federal commitments withlong-term budgetary effects—primarily loans andloan guarantees to nonfederal entities—are reportedand reflected in the budget totals on an accrual basis.(Certain transactions related to federal retirement benefits are reported on an accrual basis in agencies’ budgets,but the overall budget totals reflect the government’spayments to annuitants and employees’ contributions tothe retirement funds on a cash basis.)Usually, CBO’s cost estimates are prepared using thesame basis of measurement that the Administrationuses to measure and report the net cost (or savings) oftransactions as it executes those activities. However, forthe purpose of applying Congressional rules related tobudget enforcement, lawmakers require CBO to preparecost estimates for certain types of legislative proposalson an accrual basis even though the budget accounts forthose affected activities on a cash basis. In other situations, CBO also provides information about long-termbudgetary effects on a supplemental basis (see Table 2on page 9).Accrual-Based Budgetary TreatmentCurrently, the use of accrual measures in the budget isgoverned by laws that specify such budgetary treatmentfor particular programs or activities, or particular typesof programs. Accrual-based budgeting is mostly confinedto activities that are financial in nature, including federalcredit programs, the Troubled Asset Relief Program,U.S. contributions to the International Monetary Fund,and certain kinds of leases involving capital assets (seeFigure 1).6 The budget also reports the federal government’s interest costs as outlays when they accrue, notwhen they are paid; however, the difference betweenthe cash and accrual measures is small for most of the6. The budget records the cost of capital leases and lease-purchaseagreements up front on a present-value basis but records annualpayments for operating leases on a cash basis. See Office ofManagement and Budget, Appendix B—Budgetary Treatmentof Lease-Purchases and Leases of Capital Assets, OMB CircularNo. A-11 (August 2017), www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circularsa11 current year a11 toc. In addition, see CongressionalBudget Office, Report on the Troubled Asset Relief Program—June 2017 (June 2017), www.cbo.gov/publication/52840;The Budgetary Effects of the United States’ Participation in theInter

SAVINGS FROM LIMITING FORGIVENESS OF GRADUATE STUDENT LOANS 10 BOX 3. ACCOUNTING FOR MARKET RISK IN ACCRUAL-BASED ESTIMATES 14 Other Measures Used in the Federal Budget Process 16 Advantages and Disadvantages of Cash and Accrual Measures 18 BOX 4. INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCE WITH ACCRUAL BUDGETING: WHAT ARE THE LESSONS? 20