Transcription

Running header: COLLABORATIVE CURRICULUM“Collaborative Curriculum”Marc GoldWilliam Paterson University

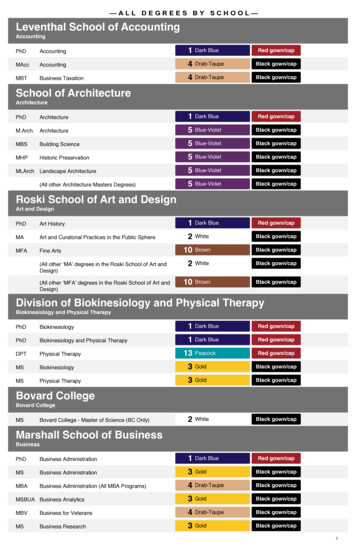

COLLABORATIVECURRICULUM2Collaborative CurriculumAccording to DuFour, DuFour, Eaker, and Many (2006), collaborative study of essentiallearning outcomes creates ownership of the curriculum among those who are asked to teach it.Within the George Washington School District (GWSD) some curricula are developedcollaboratively while supervisors within his/her selected field individually adjust the curriculum.This paper is going to explore the GWSD’s current curriculum development process bycomparing the effects of transformative curriculum process and independent curriculum process.According to Rachel Spalding, the GWSD’s Curriculum Assistant Superintendent, withinthe SOMSD, the district is on a five year curriculum cycle, in which, a specific content area isupdated (personal communication, October 19, 2010). Within these cycles, some content areas’curriculum are adjusted or written solely by the supervisor, and for other content areas thecurriculum is formed through the collaboration of the supervisor and teachers, alike. Accordingto R. Spalding, the reason she affirms a “laissez faire” approach is that she believes supervisors,within each content area, know what is most effective for his/her specific content area togenerate the curriculum (personal communication, October 19, 2010).The GWSD mathematics supervisor, Dr. Cheryl Reed utilizes the transformationalapproach in developing the curriculum for the Mathematics department. According to Dr. Reed,it is only right to break teachers up into grade levels tocollaborate and develop the curriculum. “The teachersare the ones who are most invested into the curriculumand dealing with the students on a daily basis- that it only

COLLABORATIVECURRICULUM3seems right that they have control over what they are teaching” (personal communication,October 20, 2010). According to Richardson (1997), Constructivist teachers build on learners’current understanding, interests, and needs; hence the GWSD mathematics supervisor hasallowed the teachers, who understand the students the best, to develop the curriculum. Theindividuals within the mathematics department feel a sense of empowerment to developcurriculum and are able to generate the benchmarks, objectives, and time frames on each subjectmatter.“Almost Every veteran educator would agree with the research on the huge discrepancybetween the intended curriculum and the implemented curriculum” (Marzano, 2003). Accordingto R. Spalding, about 85 percent of the staff within the GWSD teach the intended curriculum(personal communication, October 19, 2010).However, when comparing the mathematicsdepartment and the language arts department, the mathematics department has just about 100percent of the staff teaching the intended curriculum, while the language arts department hasindividuals, at times, throughout the school year implementing his/her own curriculum.According to Sallie Carson, an eighth-grade language arts teacher at Jefferson Middle School,last year, (2009-2010 school year), GWSD did not have a curriculum aligned with the schooldistrict’s goals; Therefore, some individuals within the language arts department would teachdifferent subject areas at any given time throughout the school year.Conversely, the mathematics department uses collaborative curriculum developmentaligned within the school to ensure that all students are encountering the same curriculum withthe same allotment of time. According to Rebecca Williams, a seventh grade mathematicsteacher at Jefferson Middle School, the curriculum allows for a only a specific allotment of time,or pacing guide, for each particular unit and that unit is followed with a district assessment. The

COLLABORATIVECURRICULUM4district assessments allow all students to be assessed on a standardized level- the data from thedistrict assessments are reviewed by collaborative teams of teachers to refine the curriculumbased on the data-analysis (personal communication, October 6, 2010).Jonathon Saphier (2005) contends that excellent schools us a “crystal clear curriculum” tobring academic focus, coherence, rigor, precisions, alignment, and accountability to daily workof the classroom teacher. Dr. Reed, within theGWSD, has created teacher accountability andunity by giving teachers the opportunity towork collaboratively, fitting the pieces of thepuzzle together to create a “crystal clearcurriculum”.The teachers, collectively,choose the essential learning outcomes for thecurriculum; therefore, Dr. Reed has created a culture were the teachers are empowered but areexpected to teach the intended curriculum because the teachers are the individuals whom havedeveloped the curriculum collaboratively.If the teachers have not taught the intendedcurriculum, the teachers can only blame themselves for constructing an inadequate curriculum.According to DuFour, DuFour, Eaker, and Many (2006), collaborative study of essential learningoutcomes creates ownership of the curriculum amongst those who are asked to teach it.If teachers are not immersed within the development of the curriculum process; thedirectors and supervisors, whom create the curriculum, will not be aware of the instrumental,instructional needs of the students.Vygotsky’s (1978) argues that the zone of proximaldevelopment acts as the main drive for teachers’ curriculum development. The teachers’ role isto explore “the distance between the [students’] actual developmental level, as determined, by

COLLABORATIVECURRICULUM5independent problem-solving and the level of potential development as determined throughproblem-solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (p. 86).According Marzano (2003), it could take up to 23 years to adequately cover all thestandards that have been established at the state and national levels. Therefore, the question thatpresents itself is: What happens when struggling students are not given adequate time to masterthe curriculum? According to R. Williams, the curriculum is spaced out with the essentialobjectives and specific allocated time for students whom are proficient, or master it; however forthe struggling students, there is not enough time for them to digest/understand it. There are notenough hours in the school year /day for students to master the curriculum (personalcommunication, October 6, 2010). According to DuFour etc. (2006), a system of interventionmust be arranged for these struggling students, in order, to ensure they are given supplementalsupport and time to become proficient with the curriculum. Jared Blake, Principal of JeffersonMiddle School, incorporated an intervention system that involves a collaborative effort to ensurethat the individuals, whom are struggling, will receive attention from multiple individuals, acrossthe various content areas, to ensure his/her success. This model will provide more stakeholdersinvolved in the interest/success of the student and ensure that the student understands that thereare numerous individuals that he/she could reach out to receive help. This model that Dufouretc. (2006), recommends and that Mr. Blake incorporated in his own version into JeffersonMiddle School’s climate, eases the burden on the student’s predominate teacher through acollaborative effort to reach out to assist the struggling student.When administrators and supervisors incorporate the perspectives of teachers into thecurriculum process, it will empower the teachers to feel a sense of ownership of the curriculum,opposed to teachers being handed a curriculum and asked to implement it into his/her classroom.

COLLABORATIVECURRICULUM6In agreeing with Dufour’s etc. (2006) model of assisting struggling students, a collaborativeeffort will be more effective for students and teachers, opposed to an individual teacher dealingwith the struggling student one-on-one. Therefore, a transformational and collaborative schoolclimate will lead to success in multiple locations opposed to an independent entity.

COLLABORATIVECURRICULUM7ReferencesDuFour, R., DuFour, R., Eaker, R., & Many, T. (2006). Learning by doing: A handbook forprofessional learning communities at work. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.Marzano, R. (2003). What works in schools: Translatinarch into action. Alexandria, VA:Assocaiation for Supervision and Curriculum Development.Richardson,V . (1997). Constructivist teaching and teacher education: Theory and practice. In V.Richardson (Ed.), Constructivist teacher education: Building new understandings (pp.23- 35). London: Falmer.Saphier, J. (2005). John Adam’s promise: How to have goo schools for all our children, not justfor some. Action, MA: Research for Better Teaching.Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processesCambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

comparing the effects of transformative curriculum process and independent curriculum process. According to Rachel Spalding, the GWSD's Curriculum Assistant Superintendent, within the SOMSD, the district is on a five year curriculum cycle, in which, a specific content area is updated (personal communication, October 19, 2010).