Transcription

Captive insurancecompanies of noninsurance groups –key transfer pricingconsiderations

Captive insurance companies of non-insurance groups – key transfer pricing considerationsAuthorsSebastian Ma’ileiMatej CresnikJeremy BrownHannah SimkinDeloitte Financial Services Tax2

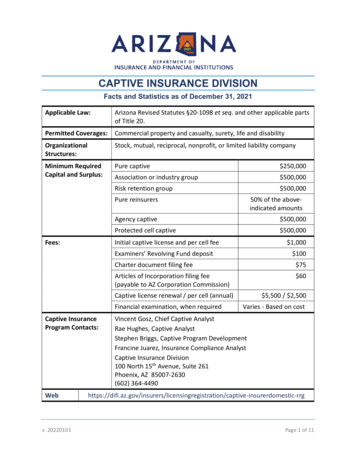

Captive insurance companies of non-insurance groups – key transfer pricing considerationsWhy now?The revised OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines issuedin July 2017 included an example on captives, and inJuly 2018, the OECD issued a Public Discussion Draftwith respect to Financial Transactions which included asection on captive insurance. In February 2020, a finalversion of this report, “Transfer Pricing Guidance onFinancial Transactions” was released, which continued toinclude material on captives and will form a new sectionof the OECD Guidelines. Concurrently, there has beenan increasing number of tax audits of captives and, insome countries, these have resulted in the matter beingreferred to the courts.With this in mind, this article is focused on two particularareas; the February 2020 OECD material on captives aswell as recent US case law on “abusive” micro-captives.What is a captive insurancecompany?But first, what is a captive insurance company (“captive”)?A captive is an insurance company created and whollyowned by a non-insurance group to underwrite risks forthe operating subsidiaries and / or the parent companyitself. In general, captive insurers: Each operating company (“OpCo”) enters into aninsurance transaction with a third-party frontingcompany for regulatory reasons. In turn, the frontingcompany places the risk with a Group captive. Fortransfer pricing purposes, even though a third partyentity is involved in the chain, tax authorities could viewthe actual controlled transaction as between the OpCoand the captive. The captive retains the risk, or a proportion of the riskand seeks external reinsurance with a third / unrelatedparty for certain layers or proportions of the risks.Captives can provide a number of key commercialbenefits to multinational enterprise (“MNE”) groups.They can provide coverage for risks that may be difficultor impossible to obtain in the open market due to, forexample, the “low frequency” and “high severity” nature ofthe risk (e.g. oil spills, contingency business interruption,product liability risk, etc.). They can reduce volatility inthe profits at the OpCo level by ring fencing assets to payclaims rather than the OpCo bearing the full economiceffect of covered losses. They can stabilise premiumspaid by group members within the multinational group,and they can help the group obtain lower premiums inthird party insurance/reinsurance markets as a result ofpooling of risks in the captive and “bulk discounts”. Put their own capital at risk; Work outside the traditional commercial insurancemarket, instead forming part of the alternative risktransfer (“ART”) market; and Are subject to regulatory, actuarial, accounting andcapital requirements.The diagram below sets out one type of captive structureand the flow of transactions for a captive:Captive insurance: Section F of theOECD’s new guidance on financialtransactionsThe OECD’s new guidance covers background oncaptives, the commercial rationale for captive insurance/ reinsurance arrangements, accurate delineation of thetransaction, and pricing methods and issues. This articlefocuses on the last two matters as these are likely to be ofmost interest to taxpayers.OpCo 13rd Party ReinsurerCaptiveFronting companyOpCo 2OpCo 3Legends:033rd partyCaptiveOpCoInsurance provisionPremium payment

Captive insurance companies of non-insurance groups – key transfer pricing considerationsAccurate delineation of transaction:A genuine insurance transaction?A significant emphasis of the new guidance is on accuratedelineation of the transaction. According to the guidance,this effectively means assessing whether the behaviourof the parties are aligned with the written terms of thelegal contract. Per paragraph 10.199 of the guidance, inorder for the transaction to be delineated as a genuinetransaction of insurance, the following criteria must bemet: There is diversification and pooling of risk in the captiveinsurance; The economic capital position of the entities within theMNE group has improved as a result of diversificationand there is therefore a real economic impact for theMNE group as a whole; Both the captive insurance and any reinsurer areregulated entities with broadly similar regulatoryregimes and regulators that require evidence of riskassumption and appropriate capital levels; The insured risk would otherwise be insurable outsidethe MNE group; The captive has the requisite skills, including investmentskills, and experience at its disposal; The captive has a real possibility of suffering losses.Whilst many of these criteria should be met bythe majority of captives, two in particular standout as potentially being at odds with some captivearrangements.The first challenge is around diversification. Theguidance stresses that this is key, as this is how thirdparty insurance companies are able to be profitable; thisharkens back to the seminal insurance industry conceptof the contributions of the many (premiums) covering thelosses of the few and the operation of the “law of largenumbers” to fairly accurately model expected losses.Third party insurance companies can quite easily achievethis through line of business (e.g. property versus liability)and geographic diversification. Even monoline insurerssuch as motor insurers can achieve diversificationthrough factors such as geography and types of driversand vehicles. For a captive insuring risks emanating only04from one MNE, however, this can be more difficult, unlessthe MNE is a conglomerate. Pharmaceutical companiesmay, for example, be most focused on insuring productliability risk in particular jurisdictions (e.g. the US),whereas a mining group might be concerned withbusiness interruption risk.The second challenge is around whether the insured riskwould otherwise be insurable outside the group. Captiveinsurance companies exist in some instances precisely toinsure risks that for all practical and commercial purposesare not insurable externally, whether because of cost, oron account of the challenges and administrative hurdles(e.g. extensive documentation required) associatedwith insuring unique or special risks with third parties.It may nevertheless be commercially rational and inthe best interests of the insured to purchase captiveinsurance coverage for risks that are not insurableexternally—which is explicitly acknowledged by theOECD in paragraph 10.194 of the new guidance in theFebruary 2020 report. Therefore, this criterion is atodds with paragraph 1.122 of the OECD Guidelines onnon-recognition, which states that “Importantly, themere fact that the transaction may not be seen betweenindependent parties does not mean that it should notbe recognised” and that only transactions that are notcommercially rational should be disregarded. In thisinstance, tax authorities could use the new guidance notto disregard a captive insurance transaction in full, as thenon-recognition criteria are not met, but rather to reprice the transaction as something other than insurance(e.g. provision of funding) under the principles of accuratedelineation.The new OECD guidance also briefly touch on substancerequirements, which fall under accurate delineationof insurance as well. In essence, the new concepts of“control over risk” and “financial capacity” in order toperform a proper risk allocation, based on actual conductrather than on contractual relationships, fully apply tocaptives. In particular, in situations in which part of theunderwriting function is outsourced to a third partyservice provider special consideration should be givento the retention of control functions. In this respect, thecompetency (educational background and professionalexperience) of the employed staff of the captive as wellas the level of information available to it needs to besufficient to exercise such control activities.

Captive insurance companies of non-insurance groups – key transfer pricing considerationsIt remains to be seen how tax authorities will interpretand apply the new rules in practice; that is, whether theytreat each of the six criteria listed above as absolutelyrequired to delineate the transaction as one of insurance,or whether achieving a majority of the six criteria issufficient to qualify as insurance. Regardless, taxpayersshould prepare and maintain evidenced transfer pricingdocumentation considering each of the above six criteriabased on the facts and circumstances of the captive inquestion.OECD Transfer Pricing approachesThe new OECD guidance also sets out which of thetransfer pricing methods may be appropriate to use forcaptive insurance transactions, including the comparableuncontrolled price method (“CUP”) as well as thetransactional net margin method (“TNMM”) where theprofit level indicators (“PLI”) are combined ratio andreturn on capital, benchmarked by reference to thirdparty insurance/reinsurance companies. However, thequality of these types of comparables vis-à-vis captiveinsurance may be in question, given the likely higher levelof diversification in third party carriers compared to acaptive. Furthermore, independent insurers/reinsurersmay have an incentive to hold additional capital (thedenominator in the return on capital calculation) overand above regulatory requirements given that additionalcapital can provide a third party insurer/reinsurer witha rating benefit from third party rating agencies such asA.M. Best. Captives generally have no such incentive tohold additional capital.The guidance also covers the concept of “groupsynergies” where the captive is used as a pooling vehicleto access the reinsurance market, e.g. by achievingeconomies of scale or by negotiating a bulk discounton premiums with a third party reinsurer, such thatthe reinsurer accepts a lower premium as a result of alarger, more diversified pool of risks in a captive. In thisinstance, the guidance stresses that any such benefitshould be passed on to the insured OpCos in the formof discounted premiums, and not retained in the captive.However, what is not considered here is that the captiveshould still be due some remuneration for whateveractivities it performs in line with basic transfer pricingprinciples, based on the functional analysis. For example,do personnel in the captive negotiate the discountedpremiums with the third party reinsurers, such that this05is an activity that should be compensated for, even if onlyon a cost plus basis?Given the challenges inherent to the above approaches,captive owners may wish to consider also performing anindependent actuarial analysis of premiums paid to thecaptive, assessing the reasonableness of key assumptionsand parameters (e.g. claims history and expenseloadings) to determine whether these assumptionsand parameters are in line with the methodologies(e.g. ‘severity’ and ‘frequency’ loss curves) used to priceinsurance premiums in the third party market. This is anapplication of an “other” transfer pricing method underthe OECD Guidelines.Conclusion: Important questions forcaptives from an OECD perspectiveFor MNEs with captives, bearing the new OECD guidancein mind, the following should be considered, evidenced,and documented: Is the transaction in question one of insurance? What is the commercial rationale for the controlledtransaction? Does the captive have the functional capability tomanage the risks ceded to it, e.g. does it employ staffwith relevant actuarial and underwriting experience? Does the captive have the capital to assume the risksceded to it? Would the controlled transaction have been agreed tobetween unrelated parties under comparable economiccircumstances? Is the premium priced on an arm’s length basis and howis this supported? Is there supporting documentation with regard to thenegotiation process and transfer pricing position?Other tax considerationsAlongside the transfer pricing treatment of captives,there are other direct tax considerations such as taxresidence and permanent establishment risks resulting

Captive insurance companies of non-insurance groups – key transfer pricing considerationsfrom remote decision-making. For example, for groupswith risk management functions based outside thejurisdiction of the captive. The delineation of buy-sideand sell-side activities in respect of the insurance forpersonnel with dual roles is key such that effectivedecision making relating to the captive takes place inthe jurisdiction of the captive.Targeted measures, such as the UK’s diverted profits tax(“DPT”) which seeks to tax profits artificially diverted fromthe UK at a punitive rate, have also prompted enquiriesinto captive arrangements where the captive is based ina low tax jurisdiction. In line with the new OECD guidanceon determining whether a captive arrangement is agenuine insurance transaction, it is important to be ableto explain to the tax authorities why the captive is used,covering both the original set-up and its continued use.HMRC’s DPT guidance contains an example of a captiveinsurance arrangement where there are no commercialmotives for the transaction other than the tax saving,concluding that a DPT charge should arise.Controlled foreign company (“CFC”) rules have also nowbeen widely implemented across the European Unionas a result of the EU’s Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive. Theapplication of CFC rules both in the EU, and more widely,to the activities of the captive should be considered.U.S. perspectiveThe application of U.S. captive tax principles may providecontext for captive developments in the OECD andprovide live examples of how a tax authority is engagingwith some captive insurance arrangements.regulations under section 482 and the OECD TransferPricing Guidelines provide guidance for ensuring arm’slength pricing of services between affiliates, whereby:“arm’s length price [should be] determined by taking intoconsideration data available on companies performingfunctions, employing assets, and assuming risks that arecomparable to those of the captive subsidiary.”The stated goal of the compliance campaign is to ensurethat U.S. multinational companies pay their foreigncaptive service providers (including captive insurancecompanies) no more than arm’s-length prices in orderto prevent erosion of the U.S. tax base. Furthermore, inFebruary 2020, the IRS announced it has established 12new teams to audit what it has deemed to be “abusive”micro-captives. A micro-captive is a captive that takes inno more than 2.2 million in annual premiums and haveelected under Internal Revenue Code section 831(b) to betaxed only on investment income (but not underwritingincome).U.S. Case Law UpdateRecently, the IRS has challenged a number of captiveinsurance arrangements in court with favourableoutcomes for the IRS. The most recent U.S. Tax Courtopinion was issued in April 2019 in the case of SyzygyInsurance Co. Inc., v Commissioner,117 T.C.M. 1165 (10April 2019), where the Tax Court held that the coverageprovided to S-corporation affiliates through a frontingarrangement by Syzygy, a captive company domiciled inDelaware, did not constitute insurance for federal incometax purposes.Specifically, captive insurance arrangements have beensubject to particular scrutiny by the IRS in recent yearsand there have been captive tax court cases decided infavour of the IRS. Given this backdrop, a U.S. update isprovided below.The Court’s analysis considered all relevant facts andcircumstances, and focused on the four commonlaw criteria that must be met for an arrangement toconstitute “insurance”:LB&I Captive Services ProviderCampaign02. Risk transfer/risk shifting from the insured to theinsurance company;In April 2019, the IRS announced a compliance campaignfocused on the pricing of intercompany arrangementswith captive service providers, including insurancecoverage issued by foreign captive insurance companies.The release largely indicates that U.S. transfer pricing0601. Insurable risk;03. Risk distribution among the insureds; and04.Commonly accepted notions of insurance.

Captive insurance companies of non-insurance groups – key transfer pricing considerationsIt is worth flagging that these four criteria overlap with theOECD’s requirements for a transaction to be accuratelydelineated as one of insurance.The Court held that Syzygy did not qualify as an insurancecompany, making it ineligible to make a section 831(b)election to exclude its underwriting income from taxableincome. The Court’s analysis specifically touched on thelast two criteria: (i) risk distribution among insureds and(ii) insurance in the “commonly accepted” sense. Theseare considered below.Distribution of RiskThe Court noted the fronting arrangement was notactuarially validated and lacked terms and rates that anarm’s-length buyer would require. As such, the Tax Courtfound that the fronting arrangement did not constitutebona fide insurance. In light of this finding, the Court heldthat the arrangement did not achieve risk distributionunder the common law test.Insurance in its commonly acceptedsenseIn analysing whether the arrangement was insurancein its commonly accepted sense, the Court identified anumber of unfavourable facts pertaining to this commonlaw criteria, including: no claims were made althoughmultiple claims could have been made, Syzygy had noestablished claims management process, more than 50percent of the asset value in the captive consisted ofinterests in two life insurance policies that had ambiguouscontractual terms, and premiums were unreasonablyhigh.Therefore, the Tax Court found that while Syzygywas adequately capitalised the arrangement was notinsurance in its commonly accepted sense.While the Court’s opinion did not specifically address(1) presence of insurable risk, and (2) risk transfer/riskshifting, it ultimately both disallowed the deductionfor premiums paid by the related party insureds andrequired Syzygy to include the insurance premiums intaxable income.The decision in this case extends the run of Tax Courtopinions unfavourable to certain types of captives,following Avrahami v. Commissioner,149 T.C. 144 (2017)07(section 831(b) “micro-captive”) and Reserve Mech. Corp.v. Commissioner,115 T.C. M. 1475 (18 June 2018)(section501(c)(15) tax exempt captive). This is also the first casein which the IRS both denied the purported insured’sdeduction for insurance premiums and the captive wasrequired to include the “premium” income in its taxableincome.U.S. Takeaways: The CaptiveEnvironmentThe decision in Syzygy and the announcement of theLB&I transfer pricing campaign for captive services,taken together with other developments, includingdesignation by the IRS of certain section 831(b) captivesas a “Dirty Dozen” tax scam, the other Tax Court decisionsnoted above, and required information reporting as a“transaction of interest” as prescribed in Notice 2016-66,evidence a trend of substantial increased scrutiny ofcaptive insurance companies by the IRS and disapprovalof certain captive insurance arrangements, based on allthe facts and circumstances of each captive, by U.S. TaxCourt.These recent developments highlight the importanceof preparing premium pricing and risk transfer (FAS113-type) analyses for all material captive transactions;this analysis should be completed by an independentand reputable actuarial firm. The reasonableness ofthe calculations should be closely reviewed. In addition,risk transfer testing associated with the captivetransactions ought to be completed and documentedcontemporaneously, particularly for transactionsinvolving loss portfolio transfers (i.e., a financialreinsurance transaction in which loss obligations that arealready incurred and will ultimately be paid are ceded to areinsurer.)In all captive cases, complete and accurate taxdocumentation of an entity’s qualification as an insurancecompany under the relevant local country rules andappropriate pricing of insurance premiums paid to acaptive are essential self-defence mechanisms for MNEsand should go a long way in the event of an audit by thetaxing authority.

Captive insurance companies of non-insurance groups – key transfer pricing considerationsContacts08Seb Ma’ileiMatej CresnikPartner – Deloitte UKUK Insurance Tax Leadsmailei@deloitte.co.uk 44 (0) 20 7007 1596Principal – Deloitte Tax LLP (US)Americas Insurance Transfer Pricing Leadmcresnik@deloitte.com (1) 212-436-7760Jeremy BrownHannah SimkinDirector – Deloitte UKFinancial Services Transfer Pricingjerebrown@deloitte.co.uk 44 (0) 20 7007 5350Associate Director – Deloitte UKFinancial Services Corporation Taxhsimkin@deloitte.co.uk 44 (0) 20 7303 4472

This publication has been written in general terms and we recommend thatyou obtain professional advice before acting or refraining from action on anyof the contents of this publication. Deloitte LLP accepts no liability for any lossoccasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of anymaterial in this publication.Deloitte LLP is a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales withregistered number OC303675 and its registered office at 1 New Street Square,London EC4A 3HQ, United Kingdom.Deloitte LLP is the United Kingdom affiliate of Deloitte NWE LLP, a member firmof Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, a UK private company limited by guarantee(“DTTL”). DTTL and each of its member firms are legally separate and independententities. DTTL and Deloitte NWE LLP do not provide services to clients. Pleasesee www.deloitte.com/ about to learn more about our global network of memberfirms. 2020 Deloitte LLP. All rights reserved.Designed by CoRe Creative Services. RITM0550574

Captive insurance companies of non-insurance groups - key transfer pricing considerations Why now? The revised OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines issued in July 2017 included an example on captives, and in July 2018, the OECD issued a Public Discussion Draft with respect to Financial Transactions which included a section on captive insurance.