Transcription

economic & COnsumer credit Analy ticsANALYSIS Housing Finance Reform Steps ForwardMarch 2014Housing Finance Reform Steps ForwardPrepared byMark ZandiMark.Zandi@moodys.comChief EconomistCristian deRitisCristian.deRitis@moodys.comSenior DirectorConsumer Credit AnalyticsContact UsEmailhelp@economy.comU.S./Canada 1.866.275.3266EMEA (London) 44.20.7772.5454(Prague) 420.224.222.929Asia/Pacific 852.3551.3077All Others 1.610.235.5299Webwww.economy.comAbstractHousing finance reform took a big step forward with the recent release of the HousingFinance Reform and Taxpayer Protection Act of 2014. The legislation sponsored bySenators Tim Johnson (D-SD) and Mike Crapo (R-ID) represents a serious bipartisanplan to wind down Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and fix the nation’s dysfunctionalhousing finance system.1

ANALYSISHousing Finance Reform Steps ForwardBy Mark Zandi AND cRISTIAN DERITISHousing finance reform took a big step forward with the recent release of the Housing Finance Reform andTaxpayer Protection Act of 2014. The legislation sponsored by Senators Tim Johnson (D-SD) and MikeCrapo (R-ID) represents a serious bipartisan plan to wind down Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and fix thenation’s dysfunctional housing finance system.1The Johnson-Crapo bill would allow foran explicit government backstop of the U.S.mortgage market, which would kick in onlyafter a financial catastrophe much worsethan the Great Recession (see “Key Provisions of Johnson-Crapo Bill” below). A significant amount of private capital would takethe risk ahead of taxpayers.With the government’s role made clear,private mortgage lenders would be able tocontinue offering 30-year fixed-rate mortgages to a broad range of creditworthyAmerican households. These popular homeloans would be available at reasonable ratesin both good times and bad. Without thegovernment backstop, 30-year fixed-ratemortgages would essentially disappear, becoming as rare in the U.S. as they are in therest of the world.2To reduce the cost of mortgage credit andto ensure that credit is available at all times,the legislation promotes the use of privatecapital from a wide range of sources. Bondguarantors, private mortgage insurers, reinsurers, and the capital markets could providecapital. The only requirement is that combined they provide the required amount ofcapital to protect taxpayers. The legislationalso works to provide a level playing fieldacross sources of capital.The legislation encourages competition,standardization and transparency to keepcosts down. Key to this is the development ofa common securitization platform that wouldoperate as a cooperative, easing the entry ofMOODY’S ANALYTICS / Copyright 2014 new bond guarantors into the system. Theplatform would establish standards for guaranteed mortgage securities that would greatlysimplify the securitization process.To make sure everyone plays by the rulesand to protect taxpayers, a new independentgovernment agency, the Federal MortgageInsurance Corp., would oversee the housingfinance system. The FMIC would resemblethe Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., whichinsures bank deposits. As the founding of theFDIC ended the cataclysmic bank runs of the1930s, the new agency would prevent similarruns on the mortgage market.The legislation deals constructively withother contentious issues in housing finance. Itwould give small lenders such as communitybanks and credit unions access to the secondary mortgage market without having to gothrough big financial institutions, which coulduse their size to their advantage.3 Small lenders would continue to be able to readily selltheir mortgage loans for cash.The legislation would also replace Fannieand Freddie’s ineffective affordable housingrules, with explicit and targeted funds to promote affordability and homeownership. Inaddition, the multifamily mortgage marketwould receive a catastrophic governmentbackstop in the legislation, which, as thefinancial crisis showed, is especially critical tothe flow of credit to low-income rental properties during bad times.The Johnson-Crapo bill is also sensitiveto transition concerns: that is, how to getfrom the current to the future one withoutdisruptions. This is critical given how important the U.S. housing and mortgage marketsare to the U.S. economy and global financial system. The legislation sets a five-yeartransition period, but there are provisions toextend this using various benchmarks. Thereis also a phase-in period for new guarantorsto be fully capitalized to FMIC standards. Thiswill help address worries that there will notbe enough private capital to support the newhousing finance system.4Winding down Fannie and FreddieIt is time to wind down Fannie and Freddie and reform the housing finance system.Since the government took over the two giant mortgage finance companies during thefinancial collapse more than five years ago,nothing has changed. The government is stillmaking nearly nine of every 10 U.S. mortgage loans, amounting to almost 1 trillionannually.5 And taxpayers are exposed to thecredit risk on two-thirds of the almost 10trillion in mortgage debt outstanding (seeChart 1).This is bad for taxpayers and home buyersand is not necessary: Private investors arewilling to take on much of this risk and, withsome safeguards, are capable of doing it.Private capital has poured into the privatemortgage insurance industry over the pastyear, and risk-sharing efforts by Fannieand Freddie with investors have been verysuccessful. With so much private capital1

ANALYSIS Housing Finance Reform Steps ForwardChart 1: Government Is on the Hook for a Lot of Riskto people who really cannot affordmortgages. Help0.72Agency MBSing disadvantaged0.82but creditworthyFannie/Freddie portfoliohouseholds become homeownersBank portfolios1.87is laudable, but5.95experience showsPrivate label securitiesthat politically0.52driven help canSecond liensbe misdirectedor abused.Sources: Federal Reserve, Moody’s AnalyticsDoing nothing and puntinginterested in participating in the mortgageon housing finance system reform meansmarket, it is an especially propitious time forthat taxpayers will ultimately bear thehousing finance reform.cost of mortgage credit risk, and not mortThe longer Fannie and Freddie stay ingage borrowers. This is not efficient, nor isgovernment hands, the more lawmakers willit appropriate.be tempted to use them for purposes unreMortgage rate impactlated to housing. This has already happened.Capitalizing the housing finance systemThe 2012 payroll tax holiday was partiallyto withstand a 10% loss is not necessary.paid for by raising the premiums Fannie andThe odds of losses this large are extremelyFreddie charge homebuyers for providing inremote—combined Fannie, Freddie, andsurance. Mortgage borrowers will be payingprivate mortgage insurers lost less than halfextra as a result over the next decade.that much in the housing crash and GreatThe housing market’s revival has allowedRecession. Yet a 10% loss level of capitalizaFannie and Freddie to again turn large proftion still has some significant benefits.7 Itits, amounting to tens of billions of dollarswould provide a fortress financial foundaeach year. Policymakers may begin to relytion, all but eliminating taxpayers’ exposureon these profits to fund future governmentto risk, and should allay any concern aboutspending, making it especially hard to letthe government charging too little for itsFannie and Freddie go.6Fannie and Freddie’s limbo status hasguarantee. Under most circumstances thefostered indecision at the two institutionsgovernment’s guarantee fee should beand their regulator, the Federal Housing Fivery small.nance Agency. Lenders who do business withA high capitalization level should alsoFannie and Freddie are unsure of the rulesdispel any moral hazard concerns that priand are thus being extra cautious, keepingvate financial institutions would lower theircredit overly tight for potential homebuyers.underwriting standards and take on tooThis can be seen in the average credit scoresmuch risk, assuming the government wouldon loans acquired by Fannie and Freddie,bail them out. It is hard to conceive that thiswhich today are in the top one-third of allwould be a problem in the Johnson-Crapocredit scores.housing finance system since private capitalLonger run, given the nation’s changingwould have so much skin in the game. Bedemographics, the concern should be thatfore the government guarantee would everFannie and Freddie under government aushave been needed, private investors wouldpices will not make the innovations neededhave suffered devastating losses.to extend loans to all creditworthy borrowers.The principal cost of requiring a 10%Politicians may also eventually becapitalization is a higher mortgage rate fortempted to force Fannie and Freddie to lendborrowers. How much higher depends onMortgage debt outstanding, trilMOODY’S ANALYTICS / Copyright 2014 many factors, but it probably would add lessthan a half percentage point to the average mortgage rate, or about 75 a monthin extra interest payments. This representsa roughly 10% increase for the typical newmortgage borrower. While meaningful, it isworth the price if it funds a rock-solid andaccessible mortgage and housing marketfor generations.Cost of capitalLimiting the mortgage-rate impact ofthe 10% capitalization in the Johnson-Crapobill is the flexibility the legislation gives theFMIC. Although capital can be provided either by the capital markets or by bond guarantors, this analysis assumes that guarantors provide the first-loss capital and sharethe risk with capital markets.The guarantors have two capital requirements. First, they must maintain sufficientequity to remain solvent in a stress test.8 TheFMIC will determine the appropriate stressscenario, but assuming they use a scenariosimilar to the severely adverse scenario inthe Federal Reserve’s Comprehensive CapitalAnalysis and Review for the nation’s largebanks, the guarantors will need to hold approximately 4% equity capital.9 It is likely nocoincidence that this is approximately equalto the combined losses suffered by Fannie,Freddie, and private mortgage insurers during the housing crash and Great Recession.It is also approximately equivalent to theamount of capital banks must hold againstthe mortgages they own under the Basel IIIcapital standards.Second, guarantors must maintain acapital ratio of 10%, although the FMIChas substantial discretion over what can beincluded in the numerator and denominator of the ratio. Capital in the numeratoris broadly defined to include “instrumentsand contracts that will absorb losses beforethe Mortgage Insurance Fund.”10 Examplesof such instruments and contracts includereinsurance, letters of credit, and futureguarantee fees to be earned by the guarantor after accounting for the stress scenario.The denominator of the capital ratio couldinclude total assets, total liabilities, risk-inforce, or unpaid principal balance.112

ANALYSIS Housing Finance Reform Steps ForwardKey Provisions of Johnson-Crapo BillThe Johnson-Crapo Housing Finance Reform and Taxpayer Protection Act of 2014 has six principal provisions:Private securitizationJohnson-Crapo requires private financial institutions put up10% in first-loss capital to qualify for a government guarantee. TheCorker-Warner plan also required a 10% private capital buffer, butJohnson-Crapo gives regulators more latitude to determine howthe capital buffer is met. Capital markets and mortgage guarantorswould provide capital with the stipulation that their loss-absorbingcapacity is equivalent.Creation of FMICJohnson-Crapo creates a new regulator, the Federal MortgageInsurance Corp., to oversee the process of insuring, securitizing andservicing mortgages and to provide an explicit government backstop for certain mortgage-backed securities.As a regulator, the FMIC would replace the FHFA, Fannie andFreddie’s current regulator, and oversee all aspects of the mortgagefinance market including the approval of loan originators and servicers. The agency would set securitization standards and underwriting requirements for any loans that end up in securities backedby the government. At a minimum, loans would have to meet thestandards for a qualified mortgage set up by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Under the legislation, the FMIC’s underwriting standards would include a down payment requirement of 3.5%for first-time homebuyers and 5% for other buyers.As a guarantor of mortgage default, the FMIC would insureapproved mortgage-backed securities through the creation of aMortgage Insurance Fund analogous to the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund. The MIF would protect investors’ losses beyond a 10%first-loss position held by private participants in the market. TheMIF would initially be capitalized through assessments charged toFannie and Freddie, but later that cost would be shifted to privatemarket participants as Fannie and Freddie are wound down. MIF’sreserves would start out at 1.25% of the unpaid principal balanceon covered securities with the reserve ratio rising to 2.5% as thefund matures.Organizationally, the FMIC would be structured similar to theFDIC with a five-member board of directors nominated by thepresident and confirmed by the Senate.Fannie, Freddie wind-downJohnson-Crapo would wind down Fannie and Freddie and significantly reduce the government’s role in the housing market. Thelegislation targets a five-year wind-down of the GSEs, but there areprovisions to extend this depending on the achievement of variousbenchmarks. The implementation of a new securitization platformMOODY’S ANALYTICS / Copyright 2014 is a vital benchmark, as is the establishment of a sufficient numberof private guarantors, aggregators, private mortgage insurers, andmultifamily guarantors.Given the complexities and sheer size of the mortgage marketand GSE portfolios, the five-year time frame is unlikely: A 10-yearhorizon seems more plausible. The FHFA has had difficulty gettingits common securitization platform project off the ground. Coordinating the thousands of players in the secondary mortgage marketand ensuring that processes are working smoothly will take time.Given how integrated the agency MBS market is with global financial markets, even the slightest hiccup in the process once it beginscould have significant consequences.Common securitization platformThe legislation calls for the establishment of a universal standardfor the MBS guaranteed by the FMIC. This standard would simplifythe securitization process and make it easier for investors to compare MBS pools. Standardization would be flexible enough to accommodate a variety of products but with an emphasis on preserving the liquidity of the 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage.The new securitization platform would operate as a cooperativeowned by its members and regulated by the FMIC. The FMIC wouldselect a five-member board to get the platform up and running.Subsequent boards would consist of nine elected directors representing members of the platform. To address concerns of smallermortgage lenders, the bill specifies that at least one of the directors must represent the interests of small mortgage lenders. Onedirector must be independent, with an eye toward ensuring that theplatform meets the public interest.Affordable housingThe bill removes the explicit housing goals now required forthe GSEs and creates a number of funds to address the issue ofaffordable housing and homeownership. A criticism of the GSEstructure is that its mandate to maintain mortgage liquiditythroughout the business cycle could conflict with its affordablehousing mandate.To avoid these conflicts in the future, the bill creates the Housing Trust Fund with a mandate to ensure that quality housing isample. In addition, the bill creates a Market Access Fund to overseethe creation of responsible lending products for underserved communities. Both of these programs would be funded by a 10-basispoint surcharge on subscribers to FMIC insurance.To address concerns of consumer advocates and mortgagebrokers, the Johnson-Crapo bill preserves the ability of consumers to lock in interest rates before closing on home purchases,and ensures that 30-year fixed-rate mortgages will be availablein the future.3

ANALYSIS Housing Finance Reform Steps ForwardSmall lendersThe legislation would establish a mutually owned cooperativeof small lenders to ensure that community banks and credit unionshave access to the secondary mortgage market. The cooperativewould provide members with access to the secondary mortgagemarket through a cash window as well as securitization services.Given that the guarantors must maintainequity of 4% to pass the solvency test, theycan satisfy the required 10% capital ratioby holding 6% in instruments and contractsthat protect the MIF against loss.The cost of providing this capital thusdepends on the FMIC’s interpretation of thelegislation. Under a liberal but reasonable interpretation, in which a guarantor holds 4%However, the rules for the cooperative would allow banks withup to 500 billion in assets to be members, while nonbank mortgage lenders would have to meet a 2.5 million net worth test. Federal Home Loan Banks could be members as well. The cooperativewould receive some of Fannie and Freddie’s existing securitizationtechnology to allow it to better compete with other large securitization firms.in common and preferred equity, risk-shareswith capital markets to provide 3% of lossabsorbing capacity, and uses future guarantee fees for the remaining 3%, the costwould currently be 69 basis points (see Table1). That is, given current interest rates andassumed return requirements, the guarantorwould have to charge mortgage borrowers69 basis points to cover their cost of capital.Table 1: Cost of Capital In Johnson-CrapoAssumptionsAfter-tax cost of common equityAfter-tax cost of preferred equityCost of debt or risk syndication (basis-point spread over Treasury)Pre-tax return on unlevered capitalTax rateJohnson-Crapo (Liberal Interpretation)Common equityPreferred equityDebt or risk syndicationPresent value of future G-feesLess: Return on cash reserves to pay for losses12%7%3002%37%Capitalization10%3%1%3%3%Cost of CapitalBps69571190-8Johnson-Crapo (Strict Interpretation)Common equityPreferred equityDebt or risk syndicationPresent value of future G-feesLess: Return on cash reserves to pay for losses10%4%0%6%0%86760180-8Bank Portfolio Under Basel IIICommon equityPreferred equityDebt or risk syndicationPresent value of future G-feesLess: Return on cash reserves to pay for losses5%4%1%0%0%77761100-10Note:These cost of capital estimates are for the typical 30-year fixed-rate mortgage borrower with an 80% loan-to-valueratio and 750 credit score.Source: Moody’s AnalyticsMOODY’S ANALYTICS / Copyright 2014 For reference, under a stricter interpretation of the capital rules by the FMIC, in whichguarantors are required to have 4% commonequity and are not permitted to use future gfees in their capital calculation, the guarantor’s cost of capital would be 86 basis points.Return assumptionsAn important assumption is that theafter-tax required return on equity capital willbe 12%. This would be consistent with largemoney center banks, which currently have a10% return on equity, and private mortgageinsurers, whose after-tax ROE is closer to 15%.More uncertain is the interest rate spreadover Treasuries that investors will requirefor the risk-sharing instruments issued bythe guarantors. The 300-basis point spreadassumed in the analysis compares with anaverage historical spread between yieldson Fannie Mae securities and Treasuriesof just over 100 basis points, a 250-basispoint spread on Baa corporate bonds (lowest, investment grade), and a 500-basispoint spread on below-investment gradecorporate bonds.The spread that will attract investors tothe new mortgage credit bonds under theJohnson-Crapo rules will depend on manyfactors, including: how much data will bemade available to investors to assess the risk;whether some average market risk is soldor whether the risk is sold bond by bond;the consistency and approach to originationstandards and representations and warranties; and even the strength of the underlyingissuer if the ultimate credit performance ofthe bond is affected by the repurchase ofindividual mortgages found to have beenunderwritten improperly.There will likely be an adjustment periodwith higher spreads until it is clear how thereforms are working out and that the liquid4

ANALYSIS Housing Finance Reform Steps ForwardChart 2: Mortgage Rates Under Housing Finance ReformCurrent mortgage rate, %PATHJohnson-CrapoNationalized systemCurrent systemPre-housing crash4.04.55.0Source: Moody’s Analyticsity for these bonds is fully established. Theguarantors need to be sufficiently capitalized, and the capital markets need to beopen so that the security can be placed.These factors are co-dependent: It is difficultfor the guarantor to price for risk that thesecurities markets will price appropriately,and vice versa.Half a percentage pointJohnson-Crapo’s impact on mortgagerates goes beyond the guarantors’ cost ofcapital. There is the 10-basis point chargeto fund the Market Access Fund and an assumed 10-basis point charge to pay for thegovernment catastrophic backstop.12 Partiallyoffsetting these higher fees will be the loweryield on government guaranteed mortgagesecurities. The explicit government guarantee should reduce the yield relative to thaton current Fannie Mae securities by 15 basispoints. The yield should be a bit lower thanGinnie Mae securities, which also receive thefull backing of the government, given theassumed liquidity benefits provided by thecommon securitization platform and singlesecurityOther aspects of the Johnson-Crapo billcut in different directions for mortgage rates.There is a possibility that despite efforts topromote entry and competition among guarantors, two or three large institutions willultimately dominate the market and becomesystemically important. There are provisionsin the legislation to establish “supplementalcapital requirements” and even to limit themarket share of too-big-to-fail institutions,MOODY’S ANALYTICS / Copyright 2014 but these wouldincrease costsand thus mortgage rates.13The commonsecuritizationplatform couldlower costsmore than anticipated throughincreased standardization,5.56.06.5better qualitydata, and theissuance of asingle security. On net, these and other factors appear to be a wash on mortgage rates,although this is a conservative assumption,and if mortgage rates under Johnson-Crapovary from levels determined by this analysis the odds favor them being lower ratherthan higher.The current interest rate on a 30-yearfixed-rate loan for a mortgage borrower witha 750 credit score and a 20% down paymentis close to 4.5%. Under Johnson-Crapo, usinga liberal but reasonable interpretation of thecapital rules, the mortgage rate for the sameborrower would be closer to 4.9%, some 40basis points higher (see Table 2). Even if theFMIC takes a somewhat tougher stance onthe capital rules, mortgage rates in JohnsonCrapo will be no more than half a percentagepoint higher than they are today.For context, under a nationalized housing finance system, in which Fannie andFreddie are permanently subsumed intothe federal government, the current fixedmortgage rate would be 4.6%. And underthe Protecting American Taxpayers andHomeowners reform legislation introducedby the House Financial Services Committee last summer, which effectively assumesa completely privatized housing financesystem with no government backstop, thefixed mortgage rate would be almost 6.3%(see Chart 2).14It is important to note that mortgagerates will be more variable throughout thebusiness cycle in Johnson-Crapo than in thecurrent system, given the more variable costof capital coming from the capital markets.Capital markets will provide cheaper capitalto the housing finance system in good times,but more costly capital in tough times.Depending on how private mortgage insurance is treated by the FMIC, this could beespecially true for borrowers with smallerdown payments, although still eligible for agovernment guarantee.Housing impactA 50-basis point increase in fixed mortgage rates under the Johnson-Crapo billwould have a measurable but very modestimpact on the housing market. To illustratethis, the Moody’s Analytics macroeconomicmodel was simulated under the assumptionthat fixed rates rise by half a percentagepoint at the start of this year.15 Three yearslater at the peak impact, home sales are lower by approximately 250,000 units, housingstarts are off by just over 100,000 units, andthe homeownership rate is almost 0.1 percentage point lower (see Table 3).Vertical integrationThere is a lot to like in the Johnson-Crapovision of the housing finance system, butit falls short in some important, yet readilyfixable respects.Significantly, the Johnson-Crapo bill allows for vertical integration in the housingfinance system. That is, financial institutionsare permitted to originate loans, aggregateloans, securitize them, and also guaranteethem. Not even Fannie and Freddie arepermitted to originate loans in the currentsystem, given the reasonable concern thiswould increase their dominance over themortgage market and exacerbate the toobig-to-fail risk they pose.While efforts to vertically integrate maybe stymied by other provisions in the legislation, such as the FMIC’s ability to raise capital standards for large institutions or evenlimit their market share, or by other regulatory requirements, Johnson-Crapo shouldmake a clear break between guarantors andoriginators: Financial institutions should beone or the other, not both.Separating originators from guarantorswould also ensure that more due diligencewould be applied to the mortgage loans and5

ANALYSIS Housing Finance Reform Steps ForwardTable 2: Mortgage Rates In Different Housing Finance SystemsBasis PointsPre-Crash GSE SystemG-feeMBS YieldServicing and Origination Compensation4202035050Current SystemG-feeCost of capitalAdministrative costsExpected lossPayroll tax surchargeYield on Mortgage SecuritiesServicing and Origination Compensation453532310101035050Johnson-Crapo (liberal interpretation)G-feeCost of capitalAdministrative costsExpected lossesMortgage Insurance FundMarket Access FundYield on Mortgage SecuritiesServicing and Origination Compensation494109691010101033550PATHG-feeCost of capitalAdministrative costsExpected lossesLiquidity Premium on mortgage securitiesFinancial Market Risk Premium on mortgage securitiesCost of FundsServicing and Origination Compensation627142123109102540050Nationalized SystemG-feeCost of capitalAdministrative costsExpected lossYield on Mortgage SecuritiesServicing and Origination Compensation4607050101034050Difference Between Johnson-Crapo and Current SystemDifference Between PATH and Current SystemDifference Between Johnson-Crapo and PATH41174133Note:Assumes current financial market conditions and servicer/orginator margins, but that the housing finance systemhas worked through any transition costs.Payroll tax g-fee surcharge expires in 2022 and is not included in the Corker Warner and PATH g-fee calculations.These mortgage rate estimates are for the typical 30-year fixed-rate mortgage borrower with an 80% loan-to-valueratio and 750 credit score.Source: Moody’s AnalyticsMOODY’S ANALYTICS / Copyright 2014 securities being originated. Independentguarantors would be especially careful intheir underwriting given how much skin inthe game they would have.Worries about regulatory overlap between the FMIC and banking regulatorswould also be addressed. Under any circumstance, the FMIC would need to coordinatewith the Federal Reserve, Securities andExchange Commission, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Consumer FinancialProtection Bureau and other agencies, butthe regulatory burden would be significantlyreduced if originators, who can be heavilyregulated depository institutions, are notpermitted to own guarantors.Then there is the issue of the small-lendermutual. Allowing lenders with up to 500billion in assets to join would open these alliances to more than small lenders. Limitingparticipation in the mutual to institutionswith no more than 100 billion in assetswould satisfy the needs of truly small lenders. This would also ensure that big lendershave an interest in ensuring a competitivenumber of viable bond guarantors.Guarantors vs. capital marketsA further concern with Johnson-Crapo isthat it allows capital markets to be in directcompetition with guarantors to providefirst-loss capital to the housing finance system. This seems sensible in theory, as thecompetition should keep costs down. But inreality this would likely be destabilizing, asguarantors could not compete with capitalmarkets when housing and financial marketconditions are good. And if guarantors cannot compete in good times, they will notbe around in bad times, when the capitalmarkets are no longer willing to providesufficient capital.The Johnson-Crapo bill recognizes this problem and works to preserve a balance betweencapital markets and guarantors. It authorizesthe FMIC “to ensure equivalent loss absorptioncapacity between approved credit risk-sharingmechanisms (capital markets) and capitalstandards for approved guarantors.”16This ostensibly gives guarantors an advantage. Since guarantors insure a diversifiedpool of mortgages over time (in good and6

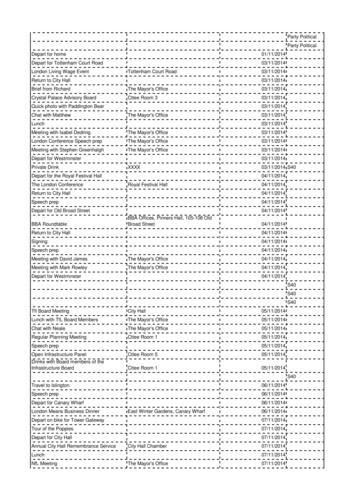

ANALYSIS Housing Finance Reform Steps ForwardTable 3: Housing Market Impact of 50-Basis Point Increase in Fixed Mortgage RatesHome sales, thsNew-home salesExisting-home salesHousing starts, thsSingle-familyMultifamilyHomeownership rate, bps2014Q1 2014Q2 2014Q3 2014Q4 2015Q1 2015Q2 2015Q3 2015Q4 2016Q1 2016Q2 2016Q3 2016Q4-84.3-88.2-81.8-77.2-81.3-91.8 -108.3 -130.6 -159.0 -189.8 -221.8 -252.8-10.9-20.0-15.7-14.0-15.2-

It is time to wind down Fannie and Fred-die and reform the housing finance system. Since the government took over the two gi-ant mortgage finance companies during the financial collapse more than five years ago, nothing has changed. The government is still making nearly nine of every 10 U.S. mort-gage loans, amounting to almost 1 trillion