Transcription

Bridging theCultural Dividein Health CareSettings TheEssentialRole ofCulturalBrokerProgramsDEVELOPED FOR:National Health Service CorpsBureau of Health ProfessionsHealth Resources and Services AdministrationU.S. Department of Health and Human ServicesDEVELOPED BY:National Center for Cultural CompetenceGeorgetown University Centerfor Child and Human DevelopmentGeorgetown University Medical Center

Bridging theCultural Dividein Health CareEssentialSettings TheRole of CulturalBroker ProgramsDEVELOPED FOR:National Health Service CorpsBureau of Health ProfessionsHealth Resources and Services AdministrationU.S. Department of Health and Human Services5600 Fishers LaneRockville, MD 20857DEVELOPED BY:National Center for Cultural CompetenceGeorgetown University Center for Childand Human DevelopmentGeorgetown University Medical CenterSPRING/SUMMER 2004

Acknowledgments This guide was developed by the National Center for Cultural Competence(NCCC) in collaboration with a work group comprising experts on a broadarray of health issues for culturally diverse and underserved populations. TheNCCC thanks the work group for its inspiring, knowledgeable, insightful, andcaring input into the process.National Work Group Members:Mirna Amaya, M.S.Counselor/Early InterventionCoordinatorMary’s Center for Maternaland Child CareWashington, DCRay Michael BridgewaterExecutive DirectorThe Assemblies of PetworthWashington, DCRosa Chaviano-Moran, D.M.D.Instructor & Admissions SpecialistUniversity of Medicine and Dentistryof New JerseyNew Jersey Dental SchoolNewark, NJJason PatnoshAssistant Director, CommunityHealthCorpsNational Association of CommunityHealth Centers, Inc.Bethesda, MDKyu Rhee, M.D.Unity Health Care, Inc.Washington, DCShadi Sahami, M.P.A./H.S.A.Research AnalystThe University of UtahSocial Research InstituteSalt Lake City, UTIra SenGuptaManager, Cultural CompetencyTraining ProgramCross Cultural Health Care ProgramSeattle, WADinah Surh, M.P.H.Vice President/AdministratorLutheran Medical Center/Sunset ParkFamily Health Center NetworkBrooklyn, NYEmma TorresCampesinos sin FronterasYuma, AZ Bridging the Cultural Divide in Health Care Settings: The Essential Role ofCultural Broker Programs reflects the contributions of the National Work Groupmembers, led by Toni Brathwaite-Fisher, BHPr Project Director, NationalCenter for Cultural Competence (NCCC), Georgetown University Center forChild and Human Development. The guide was written collaboratively byTawara Goode, Center Director, Suganya Sockalingam, Associate Director, andLisa Lopez Snyder, NCCC Consultant Writer. Additional contributions to thedocument were provided by Clare Dunne, NCCC Research Associate, andIsabella Lorenzo Hubert, NCCC Senior Policy Associate.The Essential Role of Cultural Broker Programsiii

AcknowledgmentsThis guide was developed by the NCCC for the National Health Service Corps (NHSC),Bureau of Health Professions (BHPr), Health Resources and Services Administration(HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). This project wasfunded by the BHPr. The NCCC operates under the auspices of Cooperative Agreement#U93-MC-00145-08 and is supported in part by the Maternal and Child Health Program(Title V, Social Security Act), HRSA, DHHS.Bureau of Health Professions Project Officer:David Rutstein, M.D.Chief Medical OfficerNational Health Service CorpsBureau of Health ProfessionsHealth Resources and Services AdministrationU.S. Department of Health and Human ServicesivBridging the Cultural Divide in Health Care Settings

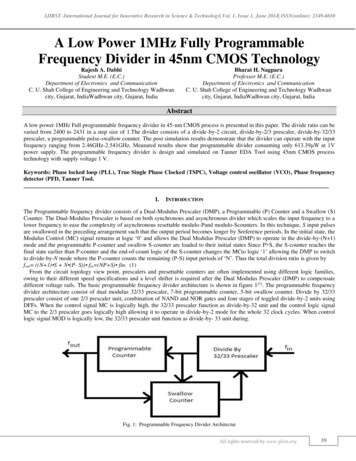

Table of ContentsAcknowledgments.iiiDefinition of Terms .viiI.Overview and Purpose of the Guide .1II.What Is the Role of Cultural Brokers in Health Care Delivery?.2III. Cultural Brokering: Benefits to Health Care Delivery Systems .6IV. Guiding Principles for Cultural Broker Programs in Health Care SettingsV.10Knowledge, Skills, and Awareness for Cultural Brokers.14VI. Implementing and Sustaining a Cultural Broker Program.15VII. Summary .17VIII. Appendix A: Impact of the Cultural Broker Program.18Empowering Girls to Take Control of TheirBodies Through Breast Cancer Detection Skills .18Low Rider Bike Club: The TeenAlternative to Drugs and Violence .19Shaman and Physicians Partner forImproving Health for Hmong Refugees.20Community Health Center’s Outreach Program to Homeless Population.21NHSC Providers Link Appalachian Communities and Care .22Native American Women Bring DateRape Education to the Classroom .23IX. Appendix B: Mission of the National Center for Cultural Competence .24X.Appendix C: Cultural Broker Contacts .25XI. References .26XII. Additional Resources.28The Essential Role of Cultural Broker Programsv

Definition of Terms acculturation: Cultural modification of an individual, group, or people byadapting to, or borrowing traits from, another culture; a merging of culturesas a result of prolonged contact. It should be noted that individuals fromculturally diverse groups may desire varying degrees of acculturation intothe dominant culture. assimilation: Assuming the cultural traditions of a given people or group. culture: An integrated pattern of human behavior that includes thoughts,communications, languages, practices, beliefs, values, customs, courtesies,rituals, manners of interacting, roles, relationships, and expected behaviors of aracial, ethnic, religious or social group; the ability to transmit the above tosucceeding generations; is dynamic in nature. cultural brokering: This term has multiple definitions. Cultural brokering isdefined as the act of bridging, linking, or mediating between groups or personsof differing cultural backgrounds for the purpose of reducing conflict orproducing change (Jezewski, 1990). A cultural broker acts as a go-between, onewho advocates on behalf of another individual or group (Jezewski & Sotnik,2001). A health care intervention through which the professional increasinglyuses cultural and health science knowledge and skills to negotiate with theclient and the health care system for an effective, beneficial health care plan(Wenger, 1995). cultural awareness: Being cognizant, observant, and conscious ofsimilarities and differences among cultural groups. cultural competence: The NCCC embraces a conceptual framework anddefinition of cultural competence that requires organizations to: have a defined set of values and principles, and demonstrate behaviors,attitudes, policies, and structures that enable them to work effectivelycross-culturally. have the capacity to (1) value diversity, (2) conduct self-assessment,(3) manage the dynamics of difference, (4) institutionalization of culturalknowledge, and (5) adapt to diversity and the cultural contexts of thecommunities they serve. incorporate the requirements above in all aspects of policy development,administration, and practice/service delivery and involve consumerssystematically (modified from Cross, Bazron, Dennis, & Isaacs, 1989). cultural sensitivity: Understanding the needs and emotions of your ownculture and the culture of others.The Essential Role of Cultural Broker Programsvii

Definition of Terms ethnic: Of or relating to large groups of people classed according to common racial,national, tribal, religious, linguistic, or cultural origin or background. ethnicity: The Institute on Medicine (IOM), in a 1999 report edited by Haynes andSmedley, defines ethnicity as how one sees oneself and how one is “seen by others as partof a group on the basis of presumed ancestry and sharing a common destiny ” Commonthreads that may tie one to an ethnic group include skin color, religion, language, customs,ancestry, and occupational or regional features. In addition, persons belonging to the sameethnic group share a unique history different from that of other ethnic groups. Usually acombination of these features identifies an ethnic group. For example, physical appearancealone does not consistently identify one as belonging to a particular ethnic group. linguistic competence: Linguistic competence is the capacity of an organization and itspersonnel to communicate effectively and to convey information in a manner that is easilyunderstood by diverse audiences. Such audiences include persons of limited Englishproficiency, those who have low literacy skills or are not literate, and individuals withdisabilities. The organization must have policy, structures, practices, procedures, anddedicated resources to support this capacity (Goode & Jones, 2003). race: There is an array of different beliefs about the definition of race and what racemeans within social, political, and biological contexts. The following definitions arerepresentative of these perspectives: Race is a tribe, people, or nation belonging to the same stock; a division of humankindpossessing traits that are transmissible by descent and sufficient to characterize it as adistinctive human type; Race is a social construct used to separate the world’s peoples. There is only one race,the human race, comprising individuals with characteristics that are more or less similarto others. Evidence from the Human Genome project indicates that the genetic code for allhuman beings is 99.9% identical; more differences exist within groups (or races) thanacross groups. The IOM report (Haynes & Smedley, Eds., 1999) states that in all instances race isa social and cultural construct. Specifically a “construct of human variability based onperceived differences in biology, physical appearance, and behavior.” The IOM adds thatthe traditional conception of race rests on the false premise that natural distinctionsgrounded in significant biological and behavioral differences can bedrawn between groups.viiiBridging the Cultural Divide in Health Care Settings

I.Overview and Purposeof the Guide Through a Cooperative Agreement, the National Health Service Corps(NHSC), Bureau of Health Professions (BHPr), funded the National Centerfor Cultural Competence (NCCC) to conduct an exciting new effort, theCultural Broker Project. The goal of this collaborative project was to encouragethe use of cultural brokering as a key approach to increasing access to, andenhancing the delivery of, culturally competent care. Cultural brokering can bedefined in many ways. Cultural brokering has been defined as “ bridging,linking or mediating between groups or persons of different culturalbackgrounds to effect change” (Jezewski, 1990). The NHSC is embracing andpromoting this concept as a viable and much-needed approach in the effectivedelivery of health care to culturally diverse populations, particularly those whoare underserved and vulnerable.The goal of the Cultural Broker Project is in keeping with the NCCC’soverall mission to “increase the capacity of health care and mental healthprograms to design, implement and evaluate culturally and linguisticallycompetent service delivery systems.” Cultural and linguistic competence haveemerged as fundamental approaches to the goal of eliminating racial and ethnicdisparities in health. A major principle of cultural competence involves workingin conjunction with natural, informal supports and helping networks withindiverse communities (Cross et al., 1989). The concept of cultural brokeringexemplifies this principle and can bridge the gap between health care providersand the communities they serve. One aspect of the project is to develop a guideto implement cultural broker programs in health care settings, particularlythose that employ or serve as placement sites for NHSC scholars andclinicians in service.This guide is designed to assist health care organizations in planning, implementing,and sustaining cultural broker programs in ways including the following: Introduce the legitimacy of cultural brokering in health care delivery tounderserved populations. Promote cultural brokering as an essential approach to increase access to careand eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health. Define the values, characteristics, areas of awareness, knowledge, and skillsrequired of a cultural broker. Provide guidance on establishing and sustaining a cultural broker programfor health care settings that is tailored to the needs and preferences of thecommunities served.This guide can serve as a resource to organizations and agencies that areinterested in partnering with health care organizations to enhance the healthand well-being of communities.The Essential Role of Cultural Broker Programs1

II.What Is the Role of CulturalBrokers in Health Care Delivery? The Concept of Cultural Brokers: A Historical OverviewThe concept of cultural brokering is an ancient one that can be traced to theearliest recorded encounters between cultures. The term cultural broker wasfirst coined by anthropologists who observed that certain individuals acted asmiddlemen, negotiators, or brokers between colonial governments and thesocieties they ruled. Different definitions of cultural brokering have evolvedover time. One definition states that cultural brokering is the act of bridging,linking, or mediating between groups or persons of different culturalbackgrounds for the purpose of reducing conflict or producing change(Jezewski, 1990). A cultural broker is defined as a go-between, one whoadvocates on behalf of another individual or group (Jezewski & Sotnik, 2001). Rationales for Cultural Brokering in Health CareThe concept of cultural brokering has evolved and permeated many aspects ofthe U.S. society, including health care. A review of literature reveals that duringthe 1960s, researchers began to use the concept of cultural brokers within thecontext of health care delivery to diverse communities. Wenger (1995) definedcultural brokering as “a health care intervention through which theprofessional increasingly uses cultural and health science knowledge and skillsto negotiate with the client and the health care system for an effective,beneficial health care plan.” Numerous rationales exist for the use of culturalbrokers in the delivery of health care. They include, but are not limited to: emergent and projected demographic trends documented in the 2000 Census inwhich the diversity in the United States is more complex than ever measured; diverse belief systems related to health, healing, and wellness; cultural variations in the perception of illness and disease and their causes; cultural influences on help-seeking behaviors and attitudes toward healthcare providers; and the use of indigenous and traditional health practices among manycultural groups.In addition, formal education may not have provided many health carepractitioners with the knowledge and skills needed to address effectivelycultural differences in their practice. Last, the need for cultural and linguisticcompetence in health care delivery systems is emerging as a fundamentalapproach in the goal to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health. Theconcept of cultural brokering is integral to such a system of care.2Bridging the Cultural Divide in Health Care Settings

Who Is the Cultural Broker?The characteristics, roles, and skills of cultural brokers are highly variable. Currently, theterm cultural broker is used to denote a range of individuals from immigrant children whonegotiate two or more cultures daily (Phillips & Crowell, 1994) to leaders in organizationswho serve as catalysts for change (Heifetz & Laurie, 1997). The range and complexity ofroles are equally varied. Cultural brokers may serve as intermediaries at the most basiclevel—bridging the cultural gap by communicating differences and similarities betweencultures. They may also serve in more sophisticated roles—mediating and negotiatingcomplex processes within organizations, government, communities, and between interestgroups or countries.One cultural broker may have extensive training and experience; another may have justbeen appointed to this role—for example, a parent in the community, or a support personin the organization—and wish to learn what is involved. In a broader sense, many staffworking in health care settings or health education programs span the boundaries of theculture of health care and the cultures of the people they serve.1. Cultural broker as a liaisonCultural brokers are knowledgeable in two realms: (1) the health values, beliefs, andpractices within their cultural group or community and (2) the health care system thatthey have learned to navigate effectively for themselves and their families. They serve ascommunicators and liaisons between the patients/consumers and the providers in thehealth care agency.These personnel can play a critical and beneficial role—on a personal level, in thecommunity in which they live, and on a professional level, in their respective agenciesor practices. These personnel effectively bridge the two worlds. Similarly, NHSCscholars and clinicians in service, who come from diverse cultural backgrounds, alsomay be effective in assuming this role and function—particularly when housed inservice areas where they have an understanding of the values, beliefs, and practicesof the community.2. Cultural broker as a cultural guideCultural brokers may serve as guides for health care settings that are in the process ofincorporating culturally and linguistically competent principles, values, and practices.They not only understand the strengths and needs of the community, but also arecognizant of the structures and functions of the health care setting. These culturalbrokers can assist in developing educational materials that will help patients/consumersto learn more about the health care setting and its functions. They also can provideguidance on implementing workforce diversity initiatives.Some organizations that are well connected to the communities they serve use acommunity member as a cultural broker because of the member’s insight andexperiences. A critical requisite for the cultural broker is having the respect and trust ofthe community. Using a community member as a cultural broker is acknowledgmentthat this expertise resides within the community. This approach also allows the healthcare setting to provide support for community development.The Essential Role of Cultural Broker Programs3

What Is the Role of Cultural Brokers in Health Care Delivery?3. Cultural broker as a mediatorCultural brokers can help to ease the historical and inherent distrust that many racially,ethnically, and culturally diverse communities have toward health care organizations.Two elements are essential to the delivery of effective services: (1) the ability to establishand maintain trust and (2) the capacity to devote sufficient time to build a meaningfulrelationship between the provider and the patient/consumer. Cultural brokers employthese skills and promote increased use of health care services within their respectivecommunities. For instance, cancer researchers have had to find ways to ease theconcerns of the African American community about participating in clinical trials. Formany African Americans, the Tuskegee study is a painful reminder of medical researchgone wrong. In that study, conducted from 1932 to 1972, poor Black men were notfully informed about their participation in medical research on syphilis. They also werenot given treatment for their disease, despite the eventual availability of drug treatment.Cultural brokers often can bridge this chasm of distrust that many cultural communitieshave toward researchers. Cultural brokers can be instrumental in reestablishing trustand reinforcing the importance of participating in research, particularly related to theelimination of racial and ethnic disparities in health.4. Cultural broker as a catalyst for changeIn many ways, cultural brokers are change agents because they can initiate thetransformation of a health care setting by creating an inclusive and collaborativeenvironment for providers and patients/consumers alike. They model and mentorbehavioral change, which can break down bias, prejudice, and other institutionalbarriers that exist in health care settings. They work toward changing intergroup andinterpersonal relationships, so that the organization can build capacity from within toadapt to the changing needs (Heifetz & Laurie, 1997) of the communities they serve.Whatever their position or roles, cultural brokers must have the capacity to: assess and understand their own cultural identities and value systems; recognize the values that guide and mold attitudes and behaviors; understand a community’s traditional health beliefs, values, and practices and changesthat occur through acculturation; understand and practice the tenets of effective cross-cultural communication,including the cultural nuances of both verbal and non-verbal communication; and advocate for the patient, to ensure the delivery of effective health services.4Bridging the Cultural Divide in Health Care Settings

Who can fulfill the role of cultural brokers in health care settings?Almost anyone can fulfill the role of a cultural broker. Most cultural brokers assumemultiple roles within health care and other settings and their respective communities.Although cultural brokers serve the same function, they come with different expectationsand have divergent experiences, yet aim to create a cultural connection.Cultural brokers may be anyof the following: outreach and lay health worker peer mentor community member (familymember, patient) administrative leader nurse, physician, physical therapist,or health care provider social worker interpreter program manager health educator board member program support personnelCultural brokers may workin these settings: community health centerscommunity-based organizationsgovernment officeschurches, mosque, kivas, plazas,temples, and other places of worshipschoolsuniversitieshospitalsfaith-based organizationsmigrant communitiesWhatever their position, cultural brokers aim to build an awareness and understanding ofthe cultural factors of the diverse communities they serve and of the ways in which suchfactors influence communities. Cultural brokers may not necessarily be members of aparticular cultural group or community. However, they must have a history and experiencewith cultural groups for which they serve as broker including: the trust and respect of the community; knowledge of values, beliefs, and health practices of cultural groups; an understanding of traditional and indigenous wellness and healing networks withindiverse communities; and experience navigating health care delivery and supportive systems within communities.The Essential Role of Cultural Broker Programs5

III.Cultural Brokering: Benefits toHealth Care Delivery SystemsThe vast network of federally qualified health centers and agencies serving indesignated health professional shortage areas will greatly benefit from acultural broker program. A cultural broker program has the potential toenhance the capacity of individuals and organizations to deliver health careservices to culturally and linguistically diverse populations, specifically thosethat are underserved, living in poverty, and vulnerable. The Health CareGrowth initiative was launched in 2001 with the goal of adding 1,200 new andexpanded health center sites to the current network and increasing the numberof people served annually to 16 million by 2006. In support of the Health CareGrowth initiative, a complementary initiative is being implemented for theNational Health Service Corps (NHSC). This initiative is designed to reformand expand the NHSC by placing more of its clinicians in areas of greatestneed. The NHSC initiative can greatly benefit from a cultural brokeringprogram by supporting system expansion to meet the needs of largerproportions of populations that are underserved and uninsured.DC PHYSICIAN CREATES AN ENVIRONMENTOF TRUST FOR HIS PATIENTSKyu Rhee, M.D., an NHSC clinician and associate medical directorwith Unity Health Care, Inc., Upper Cardozo Clinic, inWashington, DC, cares for a diverse patient population—fromSpanish-speaking persons to Asians, Ethiopians, and individuals whoare homeless—in a busy urban setting. “Cultural brokering is not arecipe approach,” he says, rather, it is the process where listening isthe essential component, one that cuts across all cultures. Bycarefully listening to his patients, Rhee says, he benefits byunderstanding his patients holistically, and thus is able to better treattheir health care problems. This benefit became starkly evident whenhe saw a woman from Zimbabwe who had suffered from headachesfor 4 years and from back and chest pain for months. After talkingwith her, Rhee discovered she had been a rape victim, had witnesseddeath as a child in her war-torn country, had left her native home,and had just been divorced. Hearing these tragedies of life is anentrée into people’s lives, he says, that can benefit the provider byhelping him or her to recognize culturalfactors affecting patients’ health andbehaviors. Dr. Rhee, in his role asassociate medical director, is able to usethe information he elicits from patientsto enhance and improve care.Additionally, as a cultural broker, he isable to use this knowledge as a vehicleto support other providers throughmentoring and inservice training.6 Benefits to the NHSCMost of the health care settings that sponsorNHSC scholars and clinicians in service are ideallocations for housing cultural broker programs.These settings include, but are not limited to,rural clinics; health departments that providecomprehensive primary care; hospital-basedprograms that have ambulatory care; suchspecialty programs as mobile clinics, homelessshelters, school-based health programs, andHIV/AIDS clinics; community mental healthprograms; academic programs that have aprimary care community-based system ofservices; tribal and migrant health programs; andthose health care settings in U.S. territories. Acultural broker program in these health caresettings can:1. assess the values, beliefs, and practices relatedto health in the community being served;2. enhance communication betweenpatients/consumers and other providers;3. advocate for the use of culturally andlinguistically competent practices in thedelivery of services; and4. assist with efforts to increase access to care andeliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health.Bridging the Cultural Divide in Health Care Settings

NHSC PROVIDERS LINK APPALACHIAN COMMUNITIES AND CAREThe Southern Ohio Health Services Network, also called the Network, instituted policy and practicesto increase access to health care and mental health services and to recruit and retain a cadre ofNHSC clinicians committed to rural Appalachian communities. The Network required physiciansto live in the communities they serve, which fostered closer ties, mutual respect, and trust betweenproviders and families. The Network also created an array of supportive services including schoolbased health clinics, multidisciplinary teams, integrated mental health services, and community-basedsocial work services. All were responsive to the needs and preferences of the families andcommunities. Such policy and practices promoted cultural brokering as an essential component in thedelivery of health care and mental health services within this Network. Kim Patton, the Network’sexecutive director, states that the physicians are more attuned to their patients’ life—from the foodsthey eat to their values, beliefs, and perceptions about health and illness. Of the 43 physicians in theNetwork’s system, 15 are NHSC providers, and many stay on with the Network after their serviceperiod expires. Providing health care using a community-focused, culturally competent approach hashelped create this continuum and improve access to services within these Appalachian communities.Another important benefit of cultural brokering is the potential to increase retention ofNHSC providers. They make a career commitment to serve vulnerable populations becauseit is a positive experience that gives them a sense of fulfillment. Benefits to the Patient/Consumer1. Patients/consumers who have positiveexperiences with cultural brokers will be morelikely to continue to access services, whichpotentially improves health outcomes andreduces health disparities.2. Patients/consumers will recognize the healthcare setting’s commitment to

National Health Service Corps Bureau of Health Professions Health Resources and Services Administration U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 DEVELOPED BY: National Center for Cultural Competence Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development Georgetown University Medical Center SPRING .