Transcription

TECHNICAL EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:Socio-economic Importanceof Ecosystem Services inthe Nordic Countries1

Synthesis in the context of The Economics ofEcosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB)Financed by the Nordic Council of Ministers (NCM) andthe Finnish NCM Presidency in 2011The synthesis of the Socio-economic Importance of Ecosystem Services in the Nordic Countries (TEEBNordic) has been developed by the Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP) and FinnishEnvironment Institute (SYKE) with contributions and support from a range of Nordic experts. Thestudy has been carried out in the context of The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB)(www.teebweb.org) and funded by the Nordic Council of Ministers in the context of the FinnishPresidency 2011 (www.norden.org).Citation:Kettunen, M., Vihervaara, P., Kinnunen, S., D’Amato, D., Badura, T., Argimon, M. and ten Brink, P.(2013) Socio-economic importance of ecosystem services in the Nordic Countries – Synthesis in thecontext of The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), Technical executive summary,Nordic Council of Ministers, CopenhagenFull report:Kettunen, M., Vihervaara, P., Kinnunen, S., D’Amato, D., Badura, T., Argimon, M. and ten Brink, P.(2013) Socio-economic importance of ecosystem services in the Nordic Countries – Synthesis in thecontext of The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), Nordic Council of Ministers,Copenhagen2

Background and contextin 2007. The objective of TEEB was to drawattention to the global economic benefitsof nature and to highlight the growingcosts of biodiversity loss and ecosystemdegradationwhilehighlightingopportunities arising from sustainablemanagement, restoration and otherappropriate conservation responses. Theultimate aim was to draw togetherexpertise from the fields of science,economics and policy to enable concreteactions for raising awareness about the“true” value of nature and integratingthese insights into decision-makingprocesses at all levels.Nature - while considered to be intrinsicallyvaluable - provides a range of benefits(ecosystem services), that fuel the globaleconomy and underpin human and societalwell-being. For example, healthy naturalsystems regulate our climate, pollinate ourcrops, prevent soil erosion and protectagainst natural hazards. They also help tomeet our energy needs and offeropportunities for recreation, culturalinspiration and spiritual fulfilment. Naturealso underpins our economies, witheconomic sectors such as cals, and food and beveragesectors directly depending on biodiversityand ecosystem services. In addition, arange of other sectors, including health andsecurity, depend indirectly on nature.However, many of the benefits provided bynature – and the associated economicvalues – are not recognised by the marketsand remain unacknowledged in decisionmaking by a range of sinesses, communities and individuals. Inother words, nature is almost invisible inthe political and individual choices wemake, resulting in us steadily drawingdown our natural capital.Since the launch of the TEEB in 2010several high level policy commitments havebeen made to integrate the value of natureinto decision-making processes at global,national and local levels. For example, boththe Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 20112020 to implement the UN Convention onBiological Diversity (CBD) and the EUBiodiversity Strategy to 2020 urgecountries to assess the socio-economicvalue of ecosystem services and integratethese values into national accounting andreporting systems. The fundamental role ofnature's capital - ecosystems, geneticresources and species - in maintaininghuman well-being is also gaining moreground in the context of broadersustainable development, e.g. as agreed inthe UN Conference on SustainableDevelopment (Rio 20) in June 2012.Nature underlines the very functioning ofour socio-economic systems, creates arange of business opportunities andprovides cost-effective solutions fordifferent sectors. The recognition thatnatural capital is fundamental for our well-The Economics of Ecosystems andBiodiversity (TEEB)A major international undertaking called‘The Economics of Ecosystems andBiodiversity’ (TEEB)1 was initiated by theEnvironment Ministers of G8 52 countries1www.teebweb.orgThe Group of Eight Five (G8 5) an internationalgroup that consists of the leaders of the heads ofgovernment from the G8 nations (Canada, France,Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom,2and the United States), plus the heads ofgovernment of the five leading emerging economies(Brazil, China, India, Mexico, and South Africa).3

being and should be appreciated for itsmany values suggests that sustainable use,protection and restoration of natureshould form a foundation for a greeneconomy, i.e. an economy that results inimproved human well-being and socialequity, while significantly reducingenvironmental risks and ecologicalscarcities.nature into decision-making processes,including possible areas for Nordiccooperation. An overarching aim of TEEBNordic was also to complement the globalTEEB initiative with interesting insights andconcrete evidence from the Nordiccountries. For this purpose six stand-alonecase studies were developed together withrelevant Nordic experts. In addition, arange of illustrative case examples wereidentified and documented.Synthesis of the socio-economicimportance of ecosystem services in theNordic countries - TEEB NordicFinally, it is to be noted that TEEB Nordichas been an independent synthesis,separate from the national ecosystemassessment currently taking place in orbeing initiated by the individual Nordiccountries. It is hoped that TEEB Nordic willprovide a useful source of information forthese national in-depth assessments.Several Nordic countries and stakeholdershave taken a stance in increasing theknowledge base on the value of nature andintegrating these insights into policies anddecision-making. In 2011, following in thefootsteps of the global initiative, the NordicCouncil of Ministers (NCM) and the NCMFinnish Presidency decided to initiate aTEEB inspired synthesis in the Nordiccontext (TEEB Nordic). The aim of thissynthesis was to bring together existinginformation on the socio-economic roleand significance of biodiversity andecosystem services for the Nordic countries(i.e. Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway andSweden).Socio-economic importance and value ofNordic ecosystem servicesThe results of TEEB Nordic reveal that,while in many ways similar to the globallevel, the range of benefits provided byecosystem services in the Nordic countriesexhibits some characteristics distinct to theregion. While provisioning servicesprovided by agriculture, forestry andfisheries still remain essential in the Nordiccountries, a number of other regionallyimportant ecosystem services can also beidentified. These include reindeer herding(especially in the north), wood-basedbioenergy, non-timber forest products suchas berries, mushrooms and game, andrecreation and tourism. In addition, thereseem to be a range of existing and novelpossibilities related to different bioinnovations (so called “bioeconomy”).Given the area coverage of forests in theregion, it is not surprising that mitigation ofclimate changes (i.e. carbon storage andsequestration) is among one of the mostsignificant – or at least most frequentlyThis stand-alone executive summarydocument presents the key outcomes ofthe Nordic synthesis. Based on the existinginformation available, the TEEB Nordicidentified the range of ecosystem servicesmaintained by healthy, well-functioningecosystems and synthesised existinginformation on the present status, trendsand socio-economic importance of theseservices. Finally, the study explored keyopportunities and priorities for futurepolicy action to integrate the true value of4

discussed - regulating services provided byNordic ecosystems. In addition, theimportance of water purification, as seenwith the eutrophication of the Baltic Sea,and pollination are often highlighted.supporting the maintenance of servicescould be identified.Insights related to the value of some keyecosystem services are provided below.More comprehensive overview of theNordic ecosystem services and their socioeconomic importance (e.g. detailedreferences for sources of information) areavailable in the main report of the study.In terms of information available, existingbiophysical data on the capacity (statusand trends) of Nordic ecosystems toprovide services consists mainly ofinformation on stocks, flows or indirectsocio-economic proxies (i.e. the use and/ordemand of service). With the exception ofprovisioning services, most of theinformation available is based on individualcase studies with very little data availableat national and regional level. Availabledata on the socio-economic value of Nordicecosystem services consists mainly ofinformation on the quantity and marketvalue of stocks. In addition, a range ofstudies could be found that reflect theappreciation and public value of ecosystemservices (i.e. people’s willingness to pay forthe improvement of services), includingwaterpurificationandrecreation.Important concrete information gapsinclude, for example, lack of estimatesreflecting broader cultural and landscapevalues, lack of data on nature’s role inmaintaining health, and lack of informationon the indirect employment impacts ofnature. In terms of ecosystems, thereseems to be considerable gaps related tomarine ecosystem services (beyondfisheries). With the exception ofprovisioning services, most of theinformation available is based on individualcase studies with very little data availableat national and regional level. Also,surprisingly few estimates were foundassessing the costs of service foregone orcosts of replacing the service. Finally, nonational or regional assessment focusingon the socio-economic role of theecosystem processes and functionsMarine and freshwater fisheries andrecreational fishingFishing in the Nordic countries is importantboth as an industry and as a hobby, leadingto a high demand for sustainablemanagement of fisheries resources.Professional fishing happens mainly onmarine areas but freshwaters are popularamongst recreational fishermen. While thenumbers of professional fishermen arefairly low across the Nordic region, thefisheries industry is of high national and/orregional importance. For example, inGreenland and Iceland (and the FaroeIslands) fisheries and fish production makethe single most significant economiccontribution to the welfare of societies. Interms of size of catches, Norway is thebiggest fish producer of the Nordiccountries (Table 1 below).Fishing is a very popular recreational hobbyin Nordic countries, and there are over sixmillion recreational fishermen (EuropeanAnglers Alliance 2002). In Finland, Swedenand Norway, 44%, 30% and 50% of thepopulation, respectively, reported havingengaged in some kind of fishing activity in5

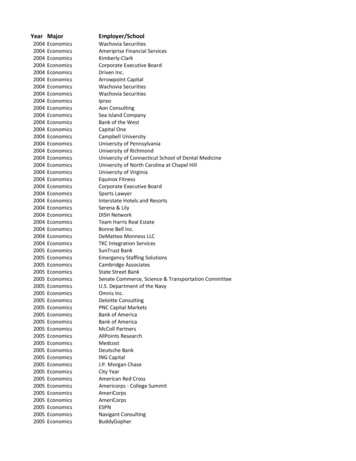

the past year. The size of catch byrecreational fishermen in Finland was 48million kg in 1998 and 79 million kg inSweden in 1995. In Sweden, the net valueof recreational fishing has been estimatedat almost 79.5 million EUR, exceeding thevalue of commercial fishing. (Sievänen andNeuvonen 2010, Statistics Sweden 2012band 2012c, Statistics Norway 2012,Toivonen et al. 2000, Garpe 2008).Table 1: Socio-economic importance and value of marine fishing in the Nordic countriesNumber ofprofessionalfishermen(incl. ,500 2,195200420052 heries 2012/StatisticIceland 2012RKTL20122,288,6231,066,428Havs ochvattenmyndigheten2012159,968132,979.2 milISK( 837 mil1EUR)201015,883.6 milNOK ( 2,1051mil EUR)3,435.5 milDKK( 462 mil1EUR)2010970.8 mil SEK1( 110 mil EUR)26.5mil EUR20112010StatisticsIceland 2012StatisticsNorway2012The DanishDirectorateof Fisheries2011StatisticsSweden 2012b,2012cRKTL2012Size of catch(tonnes)Value of thecatch (mil ofnat. currency)225,413ReferenceyearSource20051Not availableStatisticsGreenland20122011122,078Based on based on exchange rate in 2012Reindeer herdingAlthough the worldwide commercialproduction of reindeer meat is relativelysmall it is still a very significant source ofincome in Finland, Norway and Sweden. Innorth Finland, Norway and Sweden, i.e.Nordic areas where reindeer herdingremains a common source of livelihood,approximately 6,500 Sami people work asreindeer herders (Table 2 below). Reindeerhusbandry continues to be a greatimportance in the Sami region because theshipping, trading and processing of itsproducts provide numerous jobs. Althoughthe main business related to reindeerherding is meat production, reindeerherding is supported by policy action alsobecause of its cultural importance, whichgoes beyond being merely a source ofincome. As a supplement to their income,reindeer herders also engage with severalother sources of livelihood such as hunting,production of decorative items and tourism.Degrading of pastures due to overgrazing isone of the biggest challenges for reindeerherding in the future. In addition,competing land use with forestry andnatural predators might affect numbers.6

Table 2: Socio-economic importance of reindeer herding in Finland, Sweden and NorwaySource: Jernsletten and Klokov (2002)CountryHerdersReindeers(No)Finland5,600 Samiand non-Sami186,000Sweden3,500 Sami;1000 nonSami2,936 SamiNorway12Size 2160,000(34%)57 reindeerherdingcooperatives51 SamivillagesValue of production1(mil EUR)200420052006 10 1013Yes 5 57165,0002140,000(40%)80 reindeerherdingdistrictsYes 10 10 10Based on 2.5 – 2.8 (FI), 1.5 – 2.0 (SE) and 2.0 – 2.3 (NO) million kg / year production of meat in 2004-2006Data from 2000 in Finland, from 1998 in Sweden and 2001 in NorwayNon-timber forest products: berries andgameWhile there are no on-going annualstatistics on the amounts of berries andmushrooms picked and/or marketed acrossthe Nordic countries, a number ofindividual studies from Finland and Swedenprovide some estimates (Table 3 below). Ingeneral, the Nordic forests produce severaltonnes of wild berries annually with only asmall fraction of them being used, most atthe household level. The socio-economicimportance of hunting in the Nordiccountries is a combination of revenueproviding activity, household subsistencevalue, and cultural and recreationalsignificance.Table 3: Quantities and values of berries and mushrooms picked for markets in 2005 inFinland, Norway and Sweden. Source: Turtiainen and Nuutinen onnes / year)12,02713,790350Value (mil EUR)211.862132.4350.5241MushroomsQuantity(tonnes / year)426Not available500Value (mil EUR)21.019Not available1.873Value for mushrooms and berries togetherBased on the source, the estimated values for NO and FI are based on collector's price whereas in Swedishthe value is based on " weather conditions and newspaper information".27

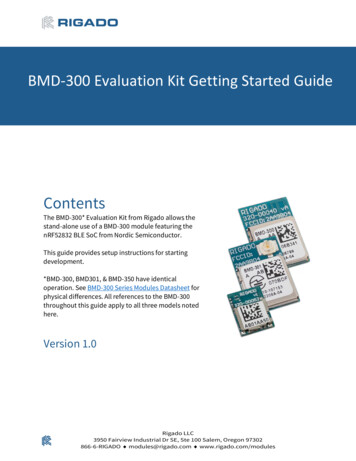

Around one million Nordic people go huntingevery year – almost 5% of the total Nordicpopulatin. Estimates for the value of gamemeat were obtained from Finland, Swedenand Norway ranging between 44 – 125million EUR (Table 4 below). In terms of thenational economy, game plays the mostsignificant role in Greenland where huntingand whaling remain an important parts ofpeople’s livelihoods. In particular, hunting isof high socio-economic importance to localcommunities in terms of cultural identity andit also remains an important means ofsupplying households with preferred meat.Table 4: Socio-economic significance of hunting in the Nordic 171,119Iceland12,227Greenland6,539Eurasian elk68,423179Eurasian elk80,974181Eurasian elk36,4003Roe ,400Woodpigeon232,100Black grouse170,000Roe deer119,000Mallard 91,500Wood n299,500Ref. yearSource2010RKTL 20122007-2008Naturvårdverket2012,StatisticsSweden 2009Willowgrouse127,850Woodpigeon56,900Red sonet al. 2010,StatisticsIceland 2012Reindeer15,092Polarbear124Guillemot84,412Harp seal84,223Ringed seal71,260Value ofgame meatRef. yearSource83 mil EUR1,119 mil SEK( 125 mil EUR)2005-2006Mattsson et al.200844 mil EURNA2010RKTL 20122001Lunnan et Greenland2012NA

Regulating services: climate regulation,water purification and pollination18 million EUR and that of wild berries(bilberries and lingonberries) would bearound 3.9 million EUR (Lehtonen 2012).In addition to pollination of commercialcrops, there are numerous home gardensin Nordic countries. An estimated value ofpollination (by honeybees) in homegardens was 39 million EUR in Finland(Yläoutinen 1994, cited in Lehtonen 2012).In Denmark the value of the general insectpollination service was calculated to beworth 421 to 690 million DKK ( 56.6 to 92.8 million EUR) a year (Axelsen et al.2011). In Sweden the value of honeybeepollination service was calculated to be189-325 million SEK ( 21.5- 37 millionEUR) (Rahbek Pedersen 2009a). Whenconsidering these values it must be notedthat insect pollination of greenhousecrops is often provided by commercialpollinators.While more research on status of andtrends in Nordic carbon storage andsequestration is required, some estimatesalready exist for the monetary value ofcarbon sequestration and storage. InFinland Matero et al (2007) estimated thevalue of carbon sequestration of Finnishforest trees to be 1 876 million EUR, andthe value of change in mineral soil carbonstock to be 136 million EUR. In SwedenGren and Svensson (2004) calculated theannual carbon sequestering value ofSwedish forest to be between 29-46billion SEK (2001 SEK) ( 3.3 – 5.2 billionEUR)basedontheestimatedconsumption value of 11-18 billion SEK( 1.2 – 2 billion EUR) and investmentvalue of 18-28 billion SEK ( 2 – 3.2 billionEUR) (See the main report for furtherdetails).While estimates are available for theglobal economic importance and value ofpollination, no such overall estimates yetexist for the Nordic countries. A recentstudy from Finland, however, assessedthat the value of honeybee pollinationservice of selected crops would be aroundFinally, in the Nordic countries manystudies have been carried out to revealthe public appreciation of cleaner surfacewaters. A summary of these is provided inTable below. In general, these studies canbe used as proxy indicators for the valueof water purification for the general public(i.e. water purification as a public good).These studies are mainly based onwillingness to pay (WTP) studies and donot, therefore, reflect market values orreal economic gains.9

Table 5: Examples of the estimated values for ecosystem’s ability to improve water quality (publicgood)ReferencesStudy areaMethodAppelblad,2001Sweden, River ByskeWTP for a day fishinglicense in the River ByskeSandstöm,1996Sweden, Laholm Bayand entire SwedishcoastRecreation benefits fromhypothetical 50% reductionof the nutrient loadSoutukorva,2001Sweden, Stockholmarchipelago,Stockholm andUppsalaSöderqvistet al, 2000Sweden, Stockholmarchipelago,Stockholm andUppsalaKosenius, AK, 2010Finland, Gulf ofFinlandRecreational benefits froma hypothetical 1-metreimprovement in waterclarity, 30% reduction ofthe nutrient concentrationsWTP (higher prices of tapwater and agriculturalproducts) for 1-metreimprovement in waterclarityWTP for three nutrientreduction scenarios ofdifferent intensities in theGulf of FinlandAtkins andBurdon2006Denmark, RandersFjord in ArhusCountyWTP for hypotheticalimprovement to obtaingood water quality in thefjord12.02 EUR / month / person over 10years, totalling 5.5 million EUR a monthover 10 yearsEggert andOlsson 2002Sweden, south-westSwedish coastWTP for preferred waterquality improvements (forbiodiversity bathing andfishing)Vesterinenet al. 2010Finland, inland andcoastal watersRecreational benefits froma hypothetical 1-metrereduction/improvement inwater clarityMean average WTP from 1,400 SEK (2002SEK) ( 159 EUR) / person for avoidingreduction in biodiversity to 600 SEK(2002 SEK) ( 68 EUR) / person forimproving biodiversity levels.Extrapolating the results over the wholeSwedish population leads to anaggregate estimate of 400 - 700 millionSEK ( 45.6 – 80 million EUR) for eitherimproving the cod stock or avoidingdeterioration of marine biodiversity.Swimming benefits loss underimpoverished environmental conditions:31-92 million EUR / year; fishing benefitsloss: 38 - 113 million EUR / year.Swimmers consumer surplus underimproved environmental conditions: 29–87 million EUR / year; fishers consumersurplus 43 - 129 million EUR / year.10Estimated impact on recreationalservicesWTP under unimproved environmentalconditions: 89 SEK ( 10 EUR); WTP underimproved conditions: 142 SEK ( 16 EUR);Consumer surplus: SEK 18 ( 2 EUR) / dayin 1996Consumer surplus: 12 - 32 million SEK( 1.3 – 3.6 million EUR) / year for theonly Laholm Bay;Consumer surplus: 240 - 540 million SEK( 27.3 – 61.6 million EUR) / year for theentire Swedish coastConsumer surplus 59 - 93 million SEK( 6.7 – 10.6 million EUR) in 1998 and70- 110 million SEK ( 8 – 12.5 millionEUR) in 1999.500 - 850 million SEK ( 57 – 97 millionEUR) / year in 199928,475 – 53,884 million EUR (total)

Recreation and tourismoutdoor life would result in 75,637 jobopportunities (Fredman et al. 2010).Nature tourism, i.e. overnight trips withactivities related to nature, is considered tobe one of the fastest growing sectors ofinternational tourism. For example inLapland, Finland nature tourism is alreadythe most important sector contributing theregional economy (Tyrväinen, 2006, citedin Bell 2007). No statistics specificallyrelated to nature tourism are available forthe Nordic counties. However, given therole nature plays in attracting tourism tothe Nordic countries, general informationon tourism can be used to indicate thesocio-economic role of nature insupporting tourism. Yearly some 100million nights are spent in different touristaccommodation establishments in Nordiccountries by domestic or foreign tourists.In addition, nature is mentioned mostoften as a main attraction of holidayhouses and there are perhaps more holidayhomes per capita in Nordic countries thananywhere else in the world (1.5 million intotal) (Müller 2007). Approximately 50% ofNordic people have access to holiday houseand in Finland the figure is over 60%(Sievänen and Neuvonen 2010). Foreigners(including Nordic visitors to other Nordiccountries) spend some 15 million nights atholiday houses.Recreation activities in nature, i.e. outdoorrecreation related to everyday life thatpeople do near their home, are extremelypopular in Nordic countries. For example,an average adult Finn does some kind ofoutdoor activity on average 170 times ayear (i.e. around three times a week, with1/3 of people doing such activity daily)(Sievänen and Neuvonen 2010). In Sweden,36-56% of people reportedly use forests forwalking at least 20 times a year (Romild etal. 2011). In Norway, hiking in forests ormountains is practised more than twice amonth by almost half of the population (i.e.around 2.4 million people) (StatisticsNorway 2012). Finally, in Denmarkapproximately 70% of Danes visited greenareas several times a week, with parks andother open natural areas being the mostpopular green areas, followed by beaches(Schipperijn et al. 2010). Outdoor life canhave significant impacts on regional andnational economies. In Sweden, the valueadded from outdoor life expenditure wascalculated to be 34,331 million SEK ( 3,918million EUR) and altogether spending onBioeconomy and bio-innovationsThere is increasing interest from Nordicand Arctic countries in researchingbiotechnological application based onNordic and Arctic genetic resources.Norway has the most developed andpromising marine biotechnology sectorfocused on Arctic genetic resources.pharmaceutical industry, e.g. cardiotoniccompounds from lily of the valley(Convallaria majalis L.) and foxglove(Digitalis purpurea L.) and enduranceincreasing compounds from roseroot(Rhodiola rosea L.) (Fabricant andFarnsworth 2001) (Box 1 below).Altogether 134 Nordic plant species havebeen identified that have medicinal oraromatic properties and that are ofFurthermore, a number of Nordic plantcompounds are currently used by the11

current socio-economic interest and thatgrow wild in the Nordic and Baltic region(Asdal et al. 2006). Recent examples ofscientific screening of Nordic plantsinclude sage species tested for their effecton type-2-diabetes in Denmark andCorydalis species on Alzheimer’s disease(Christensen 2009, Adsersen et al. 2006).Box 1: examples of Nordic bioeconomy and bio-innovationsBioremediation and removal of undesired substance: The organic waste produced by papermills is also a potential resource. Following this principle, methods to use paper mills’ wastein protein biomass production have been developed. The pekilo process, for instance, hasbeen developed in Finland for the production of single-cell feed using the fungi Paecilomycesvariotii. The first commercial pekilo plant, built at the United Paper Mills pulp plant atJämsänkoski, Finland, had an annual capacity of 10 000 tonnes of single-cell protein.Similarly, the fungi Torula utilis is used by the Boise-Cascade Corp. as a high protein foodextender and animal feed. An industrial ethanol plant connected to a sulfite pulp mill is inoperation at Örnsköldsvik in Sweden (Scheper et al. 2007).Pharmaceutical and medical uses: The Armi Project co-ordinated by the Finnish ForestResearch Institute (Metla) ran from 2001 to 2004 and isolated some 600 strains of microbesfrom boreal and Arctic environments in soil sediment, stream water, snow, lichen and mossfrom Lapland in Northern Arctic Finland and Svalbard in the Norwegian Arctic. A Europeanpharmaceuticals company has subsequently bought the rights to start screening thecollection of bacterial strains collected as part of the Armi research for anti-cancer drugcandidates. In Norway, a total of 180 million NOK ( 23.8 million EUR) has been committed tothe MabCent initiative by the Norwegian Research Council, the University of Tromsø and theassociated biotechnology companies. Approximately 25% of this funding has been providedby the commercial partners. (Leary 2008)Nordic medicinal plants: One of the most interesting medicinal plants in the world isroseroot, Rhodiola rosea L., (which grows wild in Nordic mountainous areas and is rare intemperate regions). Roseroot is said to be the northern ginseng and there are severalroseroot products on the markets. In traditional medicine roseroot has been used forphysical endurance, resistance to altitude sickness and in treatment of fatigue anddepression. Worldwide there is high demand for roseroot, especially in the U.S, and thedemand is calculated to be approximately 20-30 tonnes / year. Due to high demand wildroseroot has become seriously threatened species in Russia and in central Europe. There isno current threat to wild roseroot populations in Nordic countries and also successfulcultivation trials of roseroot have been made in Nordic countries. (Asdal et al. 2006,Economo and Galambosi 2003)Blue mussel farming to improve water quality: In Sweden, several initiatives and pilotprojects are underway to use Blue mussel farming to improve water quality. In LysekilMunicipality, a payment mechanism has been set up whereby the polluter (the local wastewater plant) pays mussel farmers to remove nutrients from the coastal waters. Payments12

are based on the content of nitrogen and phosphorous in the harvested mussels. Projectresults show that 3,500 tonnes of blue mussels/year help to remove 100% of the nitrogenemissions of the Lysekil waste water treatment plant. The use of mussels to clean thenitrogen content of the waste water plant saves the municipality close to 100,000 EUR/yearcompared to using a traditional technique (Zandersen et al. 2009).Conclusions and recommendationsDespite the significant gaps in the existingknowledge base, it is evident that a rangeof ecosystem services are of high socioeconomic significance for the Nordiccountries, either based on their marketvalue or estimated value for the broaderpublic. Natural capital (biodiversity,ecosystems and related services) alsounderpin socio-economic well-being in theNordic countries. On the other hand, basedon the existing evidence based it is alsoclear that several of these ecosystemservices including, for example, marinefisheries,waterpurificationandpollination, have been seriously degradedand several others, such as carbon storage,are facing serious risks. In addition, ratheralarmingly the information available doesnot yet allow any conclusions to be drawnon the status of and trends in the majorityof services, including processes andfunctions supporting their maintenance.are needed to address the situation. Nordiccountries are already well on their waytowards a transition to a green economy.While the approaches taken towards“greening” the economy (or economies)are likely to differ between countries, theresults presented in this report clearlyindicate that future developments shouldbe based on a sound appreciation of thevalue and role of nature in underpinningsustainable socio-economic development.The outcomes of TEEB Nordic emphasisethat the first step towards integrating thevalue of ecosystem services into Nordicpolicies and decision-making processeswould be to identify and develop acommon set of indicators to assess andmonitor the status, trends and socioeconomic v

the Nordic synthesis. Based on the existing information available, the TEEB Nordic identified the range of ecosystem services maintained by healthy, well-functioning ecosystems and synthesised existing information on the present status, trends and socio-economic importance of these services. Finally, the study explored key