Transcription

ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS FORSUCCESSFUL CO-LEADERSHIPIN NON-PROFIT THEATREBY ARIN D. SULLIVANSPRING 2012

THESISPresented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements forThe Master of Science in Arts Administration Drexel UniversityByArin D. Sullivan, B.A.*****Drexel University2012ii

Copyright byArin Sullivan2012

ABSTRACTThe organizational charts of nonprofit professional regional theatres aredominated by a dual or co-leadership structure consisting of an artistic andadministrative leader. While conflict within this leadership couple can have farreaching effects on organizational performance, little guidance has been provided forthe artists and managers embarking on this arranged marriage.Through an examination organizational behavior and human resourcesliterature describing the dual leadership relationship in nonprofit theatre incombination with an examination of literature related to CEO/COO partnerships aswell as team or group leadership texts, Successful co-leadership teams have incommon four essential characteristics: a shared essential mission, a foundation ofrespect and trust, constant and meaningful communication, and an extendedengagement. These characteristics should be considered carefully in forming coleadership partnerships.DEDICATIONii

Dedicated to my co-leader for this lifetime, Andrea Taylor, to whom I send all of mylove, trust and respect.iii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThroughout my career, I have been very lucky to be surrounded by successfultheatre professionals who have been willing to take me under their wings. When thetime comes, I hope that I have the grace to demonstrate an equal generosity of spiritwhen an annoying know-it-all next sits in front of me with lots of questions and evenmore opinions.I would especially like to thank Marge Betley, my friend and mentor, whosuffered more interruptions than most, and who inspired this thesis during many latenight conversations about the world as we would run it.I would also like to thank Cecelia Fitzgibbon who gently, and then not sogently, nudged me to finally sit down and start writing.iv

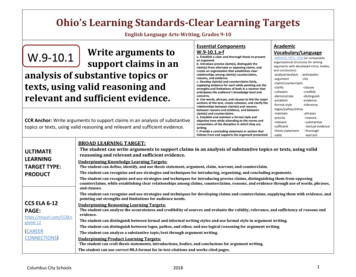

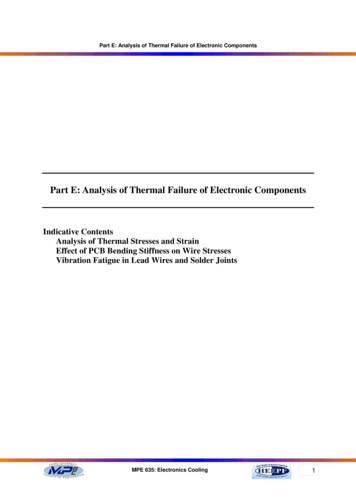

TABLE OF CONTENTSABSTRACT .iiACKNOWLEDGMENTS . ivTABLE OF CONTENTS . vLIST OF FIGURES . viINTRODUCTION . 1CO-LEADERSHIP IN NONPROFIT PROFESSIONAL THEATRE . 3FOR-PROFIT LEADERSHIP DUOS . 6LITERATURE REVIEW . 7CONFLICT . 10ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS FOR SUCCESSFUL SHARED LEADERSHIP . 13Shared Mission, Vision and Goals . 13Respect and Trust . 16Communication . 18An Extended Engagement . 20RECOMMENDATIONS . 22CONCLUSION . 23SOURCES CITED . 28v

LIST OF FIGURESFIGURE 1: CURRENT LEADERSHIP AT LORT THEATRES . 24FIGURE 2: THE LEADERSHIP TRIANGLE . 27vi

"In my consulting experiences, I have heard many board members lament theconcerns of the ‘two-headed monster’ in reference to the artistic director andmanaging director.” – Jom Volz 1"Tensions are to be expected and worked through, always remembering that whiletheatre is a business, its business is art, not business." -- Zelda Fichandler 2INTRODUCTIONThe organizational charts of nonprofit professional regional theatres aredominated by a dual or co-leadership structure consisting of an artistic andadministrative leader (see Figure 1). While conflict within this leadership couple canhave far-reaching effects on organizational performance (Voss, Cable, and Voss2006), little guidance has been provided for the artists and managers embarking onthis arranged marriage (Gronn, P., 1999; Mehta, Z., 2003).In order to inform the formation and maintenance of successful co-leadershippartnerships in nonprofit professional theatre, it is helpful to examine of the availableliterature focusing on nonprofit theatre, previously documented interviews withartistic and managing directors, as well as to examine literature in the fields of1Jim Volz, How to Run a Theater: A Witty, Practical and Fun Guide to Arts Management (New York: BackStage Books, 2004).2Zelda Fichandler, "Whither (Or Wither) Art?" in American Theatre Reader: Essays and Conversations fromAmerican Theatre Magazine, ed. American Theatre Magazine Staff (New York, NY, USA: TheatreCommunications Group, 2009), 262.1

organizational behavior and human resources. This examination yields fourcharacteristics common to successful co-leadership relationships: shared mission,mutual trust and respect, constant communication, and an extended engagement.2

CO-LEADERSHIP IN NONPROFIT PROFESSIONAL THEATREIn the second half of the 20th Century, a series of financial incentives led to arapid growth in the number of theatres in the United States. In 1962 the FordFoundation began to provide major operating support for performing artsorganizations, including millions of dollars granted to fledgling resident theatrecompanies outside of New York City, much of it in the form of matching grants inorder to recruit new donors . Following Ford’s leadership, hundreds of foundationsand corporations became active supporters of the arts (McCarthy and others 2001).In 1965, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) was inaugurated and thefederal government began to provide direct support to the arts.McDaniel and Thorn (1992) liken this convergence of funding opportunitiesto a “cultural big bang” wherein a great number of organizations were formedrapidly and without the time to organically develop organizational structures.Instead, these new theatres borrowed the key elements of their structures from othernonprofit performing arts organizations such as symphony orchestras, thus becomingstructurally isomorphic (Peterson 1986; McNeil 2009; Meyer and Rowan 1977).Isomorphism brings with it language and labels, which are used to demonstratecommonality with other like organizations and to give the organization instantlegitimacy in its nascent stages (Meyer and Rowan 1977).3

The co-leadership structure was further reinforced by the 1965 RockefellerBrothers Fund report “The Performing Arts: Problems and Prospects” (1965). In thisreport, the panel strongly recommends that nonprofit performing arts organizationshave a business professional in a leadership role, writing “Indeed, there is no reasonwhy the business operations of a nonprofit organization should not be as expertlymanaged as those of any profit-seeking organization.”Co-leadership has been described as a balanced partnership, providing whatVolz calls “checks and balances” lending to the credibility of the institution (2004,pg. 25). Gronn (1999, pg. 2) describes formal and informal “leadership couples” as a“neglected substitute for the single handed leader” and Miles and Watkins (2007, pg.4) discuss an executive team in which the members exploit their distinct strengths –what they call “complementarity.” They describe a leadership team in which thecomplementary strengths of each member both compensate for the shortcomings ofthe other team member and “results in a team in which the whole is much greaterthan the sum of the parts." According to de Voogt (2006), arts organizations musthave two leaders as it is nearly impossible to combine the required artistic andbusiness skills required to lead an arts organization in one person.Finally, theatre is, at its very core, a collaborative art form. The artisticdirector/managing director partnership may also be an outgrowth of thatcollaborative spirit (Caust 2010).4

Whether as a form of isomorphism, in reaction to the recommendations of thefunding community, to position a complete and balanced skill-set at the top, or as anoutgrowth of the collaborative spirit inherent to the creation of theatre, anorganizational structure developed in nonprofit regional theatre headed by what hasbeen described as the leadership triangle (Langley 1990): an artistic director and amanaging director of equal status, both reporting directly to the board (see Figure 2).5

FOR-PROFIT LEADERSHIP DUOSDual or co-leadership has been thoroughly explored as it relates to the ChiefExecutive Officer/Chief Operations Officer (CEO/COO) relationship in for-profitbusinesses. Although there is much that we can learn from the CEO/COOrelationship, this leadership structure is distinct from the nonprofit co-leadershipmodel in three significant ways:1. The CEO/COO relationship is a hierarchical relationship in which theCOO reports to the CEO unlike the equal status structure being examinedhere.2. While the artistic director and managing director are hired independentlyby the board, the COO is often hired by the CEO.3. The roles of the artistic director and managing director areinstitutionalized and divided according to function, while the CEO andCOO roles have similar functions where responsibilities can be assignedorganically between the two.6

LITERATURE REVIEWWhile there is no shortage of theatre management texts which refer to theartistic director/managing director partnership as the common organizationalstructure in nonprofit theatre, very little attention has been paid to the characteristicsof the relationship between the two leaders.There are references to desirable personality traits or characteristics in thebusiness half of the co-leadership duo. The Rockefeller Brothers Fund’s (1965, pg.161) report on the performing arts describes the managing director as,“knowledgeable in the art with which he is concerned, an impresario, labornegotiator, diplomat, educator, publicity and public relations expert, politician,skilled businessman, a social sophisticate, a servant of the community, a tirelessleader - becomingly humble before authority - a teacher, a tyrant, and a continuingstudent of the arts.” Langley (1990, pg. 24) describes a good manager with “taste,sensitivity and erudition whose inclinations and education make that person able toseek, recognize, support and develop the genius of artistic originality in whateverguise it may appear. Notably, both descriptions include a knowledge of and respectfor the art.However, while Volz, (2004) Conte and Langley (2007) make references tothe job of the artistic director – to guide artistic vision and maintain artistic quality –desirable personality traits of artistic directors receive no attention. This implies that7

the most desirable quality in an artistic director is the ability to envision and produceexcellent art.The artistic and managing directors are often viewed as the embodiment ofthe dual motivations of nonprofit arts and cultural organizations, i.e. art versusbusiness. The dual goals of commerce and art have been described as a paradox,(Conte and Langley 2007; DeFillippi, Grabher, and Jones 2007; Langworthy 1995;Reid and Karambayya 2009) and the oftentimes paradoxical motivations of the duohave been discussed as a cause of potential conflict in the relationship (Reid andKarambayya 2009; Glynn 2000; Voss, Cable, and Voss 2006).Glynn (2000, pg. 287) posits that the identity of cultural institutions iscomposed of "contradictory identity elements - normative artistry and utilitarianeconomics" coexisting and being claimed by different "units" within theorganization. These contradictions are institutionalized in the form of theorganizational structure. Glynn goes on to describe conflict between the twoideologies as "almost inevitable.” In their journal article “Impact of dual executiveleadership dynamics in creative organizations,” Reid and Karambayya (2009)describe the relationship between the artistic and business leaders in creativeorganizations as “laden in conflict” and “paradoxical” due to the leaders’ differingorganizational priorities. These opposing imperatives or “polarities” are seen asintrinsic to cultural industries (Lampel, Lant, and Shamsie 2000) and the tension8

between artistic and financial sensibilities is referenced directly or obliquely in allrelated literature.Additionally, MacNeill and Tonks (2009) have studied the relationship of theduo as it relates to the in nonprofit arts organizations in Australia. It is important tonote the structure in each of the organizations studied was a hierarchical leadershipmodel c

theatre is a business, its business is art, not business." -- Zelda Fichandler2 INTRODUCTION The organizational charts of nonprofit professional regional theatres are dominated by a dual or co-leadership structure consisting of an artistic and administrative leader (see Figure 1). While conflict within this leadership couple can have far-reaching effects on organizational performance (Voss .