Transcription

Person-centredcare in 2017Evidence from service users

Primary full colourThis is the primary logoto use. This is your maingo-to version of the logo,except for limitedexceptions below.Primary single colourThis is the single colourversion, and can be used inenvironments that mightrequire a cleaner aesthetic.Full tone greyscaleThe greyscale version canbe used for higher quality,but still B/W printhalftone screen is used.Solid blackThe solid black version is onlyto be used for Fax, and someforms of black/whitecommercial printingapplications, such as localnewspapers etc,where course halftonesscreens are used.National Voices is the coalition of charities thatstands for people being in control of their healthand care.We want person-centred care: people havingas much control and influence as possible overdecisions that affect their own health and care —as patients, carers and members of communities.We want people to be partners in the design ofservices and partners in research, innovation andimprovement.We help people and organisations to improve theknowledge, understanding, skills and confidencethey need to engage more effectively, and tomake their approaches more person-centred.We have expertise in what matters to peoplerelating to health and care, how to involve people,and how to work with the Voluntary Communityand Social Enterprise sector.Social mediaThere two versions of theEach are saved withtransparent backgrounds.destinations, such as: Google ,such as: Twitter, Facebook etc, and isInstagram, avatars etc and as suchplaced within Saraha container(shown asPolicy Adviser,Researcher:Hutchinson,doesNationalnot come inside a container.cyan and magenta key-lines).VoicesEditor: Don Redding, Director of Policy, National VoicesContent and production support: Andrew McCracken,Jeremy Taylor, Laura Bell, Michael Bourke, Hannah West,and the Tin Can Collective.This project was generously supported by The HealthFoundation. National Voices, September 2017

IntroductionResearch scopePolicy makers have been aspiring to a‘patient-centred NHS’ in England for atleast 20 yearsi.This report attempts to create a snapshotof the extent of person-centred carein the English health and care system,based on how people report theirexperience of treatment, care andsupport.In 2008, patient experience becamea key part of the national definition ofquality in healthcareii; and in 2012 thatwas codified in lawiii.Person-centred care has become anincreasingly prominent stated ambitionboth of national policy and localpractice. In 2013, the Department ofHealth and all the system leading bodiesacross health and social care in Englanddeclared a shared commitment tomaking ‘person-centred coordinatedcare’ the normiv.What difference, if any, have these statedambitions made to the experiences ofpeople who need and use services andsupport? We wanted to know.National Voices stands for people beingin control of their health and carev. From2011 we have been at the forefront ofmaking the case for person-centred care.There is a growing body of evidencethat person-centred approaches areimportant for ensuring the overall qualityof care and for improving health andwellbeing outcomes.This data can be found — in patches —in surveys of patients and service users.There have been previous attempts atthis task, in reports from Picker InstituteEurope [2007]vi, The King’s Fund/PickerInstitute Europe [2015]vii and The HealthFoundation [2015]viii. These looked justat the NHS, through the lens of nationalpatient surveys. We have examined bothhealth and social care, in a contextwhere integrated care has assumedgreater importance. And while thenational survey data remain our keysource, we have drawn on additionalevidence.We found that, while we can report withconfidence on some key aspects ofperson-centred care, on others the datais severely inadequate or absolutelylacking. Our conclusions about whatshould be measured are therefore atleast as important as our findings onwhat people experience.3

Executive summaryWhy did we conduct thisresearch?Over the last 20 years person-centredcare has become an increasinglyprominent national ambition. We wantedto know what difference, if any, this hasmade to the experiences of people whoneed and use services and support.How did we conduct thisresearch?We focused on a small number of keyingredients of person–centred care:how people experienced information,communication, participation indecisions, care planning and carecoordination. We also looked at family,carers and the varying experiences ofparticular groups of patients and serviceusers.What did we conclude?People’s experiences can be highlyvariable depending which services theyuse, what their needs are, and who theyare.Some aspects of person-centredcare have improvedSome of the domains that enableperson-centred care are being achieved:information and communicationin healthcare have improved, andpersonalisation in adult social care isadvanced.Progress towards involvement indecisions and being in controlThere have been advances towardspeople being involved in decisions andbeing in control of their lives and theircare, especially for specific groups.In mainstream healthcare and someresidential settings the findings are worse,showing that there is still further to go oninvolvement.Progress at riskPerson-centred care isinadequately measuredCurrently, we cannot fully measure orassess person-centred care acrossservices.A mixed pictureFrom the patchy data available itappears some aspects of person-centredcare are being consistently achieved inmainstream services. Others are not, oraren’t even being measured.4Recently, there has been some small butsignificant deterioration in the indicatorsfor person-centred care in both generalpractice (2017) and hospital inpatientcare (2016).Little evidence of personalised careand support planningDespite it being central to person-centredcare, evidence about the extent andquality of personalised care planning isvery patchy, but suggests that in mostmainstream NHS settings — and in someresidential care — it is largely absent.

Coordination of care is notmeasuredNeither the NHS nor adult social carecan demonstrate, from people’s reportsof their experience, that they arecoordinating care around the person.Family involvement is not central,and most carers need bettersupportFamily involvement appears toremain marginal to the practice andmeasurement of person-centred care.Some carers have received additionalhelp, but the majority are not gettingsupport for their own needs.Some indications of inequalitiesThere is some evidence that certaingroups are less likely to report positivelyon the domains of person-centred care. Support a small number of superdemonstrator sites to develop theseapproaches at scale Commission a pool of VCSE partnersable to support local systems todevelop person-centred, communityfocused interventions.The need for a strategic overhaul ofmeasurementWhat matters is what gets measured.Person-centred care is not adequatelymeasured. If it is to become mainstreampractice, and be seen to be achieved,the current measures need to evolve.Our findings suggest it is time fora strategic review and overhaul ofperson-centred care measures acrosshealth and care, based on commonoutcomes, for the era of integrated andaccountable care systems.What are the implications?The need for person-centred care tobe given greater priorityThese very mixed findings are consistentwith person-centred care being anambition, but not yet a priority. Thereport to the Chief Executive of NHSEngland in January 2017 by the Peopleand Communities Boardix, chaired byNational Voices, included the followingrecommendations, among others: Make person-centred and communitybased approaches part of normalbusiness Make a clear commitment to developnew, simplified, cross sector outcomemeasures5

Key findings1.Person-centredcare is inadequatelymeasured.2.A mixed picture: people’sexperiences can be highlyvariable.?Currently, we cannot adequatelymeasure or assess personcentred care across services.“Our most cruel failure inhow we treat the sick andthe aged is the failure torecognise that they havepriorities beyond merelybeing safe and livinglonger.”Atul Gawande, surgeon, writer, andPublic Health Researcher6From the patchy data availableit appears some aspects ofperson-centred care are beingconsistently achieved, butpeople’s experiences can behighly variable.“If I am listened to, myhealth care becomes apartnership, I am no longeralone in my experience.”Lissa J Haycock, Senior Peer Trainer,Brighton & Hove Recovery College

3.Some aspects of personcentred care haveimproved.76%76% of inpatientswho had anoperation orprocedure saidthat what wouldhappen was‘completely’explained.78%78% of cancer patients weredefinitely as involved asmuch as they wanted to be indecisions about their treatment.87% of generalpractice patientssaid their GP wasgood at listeningto them.87%4.Progress towardsinvolvement in decisions andbeing in control.44%33%33% of people using adult socialcare said they had as muchcontrol over their daily lives asthey wanted; another 44% had‘adequate’ control.7

5.Steady progress is now deteriorating,both for general practice and inpatientcare.Areas of progress:Involvement indecisions(hospital inpatients)80%70%Getting enoughinformation whenleaving hospital(hospital inpatients)60%50%40%Giving enough time(GP patients)30%Listening (GP patients)20%Involving people indecisions about care(GP patients)20112012201320142015201620176.Little evidence of personalised care andsupport planning3%Only 3% ofpeople witha long-termcondition saidthey had awritten care plan.8

7.Coordinationof care is notmeasured.64%64% rise in delayed transfers outof hospital in last five years.8.Family involvement is notcentral, and most carersneed better support.68% of carers saidthat their GP knewthey were a carerbut did not doanything differentlyas a result.68%46%23%46% of inpatients said they didnot get enough further supportto recover or manage theircondition after leaving hospital.23% of carers said they’d hada social care assessment.9

9.Some indicators of inequality.People who said “my GP was verygood at involving me” by ethnicity:41%32%Parents of children and youngpeople who said that hospital staffdefinitely knew how to care fortheir individual or special iginThe NHS pledges to: provide you with the informationand support you need toinfluence and scrutinise theplanning and delivery of NHSservices work in partnership withyou, your family, carers andrepresentatives10Childrenwith physicaldisabilitiesChildrenwithoutdisabilities involve you in discussions aboutplanning your care and to offeryou a written record of what isagreed if you want one encourage and welcomefeedback on your health andcare experiences and use this toimprove services.NHS Constitution, 2012

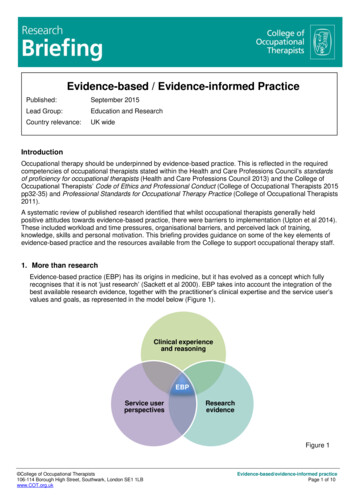

About this researchMethodologyWhat is person-centred care?There is no single definition of personcentred care, and we have notattempted to create one. Person-centredcare is generally understood to meanan approach which is holistic, meets theperson’s needs and priorities before thoseof the system or its professionals, engagespeople in their care as fully as possible,and attempts to support people to takedecisions and to be as much in controlas possible.In adult social care, partly in responseto the advocacy of service users,‘personalisation’ has developed over thelast two decades to be recognised asformal mainstream practice.In healthcare, over the same period,advocates initially emphasised ‘patientcentred care’. In the last six years this hasevolved into ‘person-centred care’ for anumber of reasons: The recognition that staff are peopletoo, and need equally to be engagedin more personalised approaches; The word ‘patient’ symbolises thedependency that personalisation aimsto overcome; and In an era of increasing integration,‘patient’ is the wrong word to describeusers of some of these services, suchas social care.There are definitions of personcentred care available. Some aimfor comprehensive status by trying toenclose ‘all’ the features that might berelevant. Among these are:The Picker PrinciplesThese are eight principles set out bythe Picker Institutex, based on empiricalresearch into what is important topatients. These have formed the basisfor further derived definitions, as well asfor patient experience measurementsystems in the US, UK and parts of Europe.Dating from the ‘patient-centred’ period,they focus on the receipt of healthcare informal settings.The Narrative for person-centredcoordinated careIn 2013 the Department of Health andall system leading bodies in health andcare in England adopted a ‘SharedCommitment’ to pursue integrated carexi.This included a shared ‘Narrative’ —produced by National Voices and ThinkLocal Act Personal (TLAP) -- describingthe goal of integration as being ‘personcentred coordinated care’; and listingmany of the things people wouldexperience if it was achievedxii. Thiscovered health, social care and othersupport, but was produced to define‘integrated care’, not to define ‘personcentred care’, and would be incompletefor the latter objective.11

The World Health OrganisationFrameworkxiiiIn 2016 all member states agreed theWorld Health Organisation’s Frameworkfor Integrated, People-Centred HealthSystems. This includes a 135-wordparagraph which stretches the definitionbeyond both ‘patient’ and ‘person’centred care, to embrace participation inservice design, education and support,population health and communityresilience.The Health Foundationreith dignity,ion, respectis tEnablingcaressPertedinaord arecPersonatedwCosonca alisre edOther definitions aim to be concise,so as to provide a more useful tool forprofessionals. For example, The HealthFoundation has produced a summarydefinition which attempts to condenseperson-centred care into four principlesxiv:paco mThe four principles of person-centredcareFive domainsFor the purposes of this report, NationalVoices has focused on a short range ofthe most common features of personcentred care that are recognisable fromacross the 20 years of discussion — andfor which indicators might be available(though not in all cases).12We believe the following would berecognised as key aspects of personcentred care by most stakeholders inthe system, both at policy and practicelevels, and by people who need and useservices and support. Information is the foundation forpeople to be engaged in their health,care and support. Tailored information— that makes it useful for the individual— is the first step to ‘personalisation’.Information may come in many forms,but in care contexts Communication between peopleand staff is the principal way in whichinformation is conveyed, discussedand tailored. More than that, it is theopportunity for the person to surfacetheir own expertise, feelings, valuesand preferences. Communicationshould be two-way and as equal aspossible. This in turn makes possible Participation in decisions as amarker for care that is enabling andempowering, and where people’sown values and preferences can bebrought to bear. An advanced form ofdecision making is Care planning so that people canconsider the future course of their care,treatment and support, and direct it asmuch as possible. Personalised careand support planning can enablepeople to identify their goals (for theirlives, not just their treatment) anddevelop a sense of control. People’sability to achieve progress towardsthese goals is then helped by Care coordination so that care andsupport are built around the individualand their carer(s), with servicesworking together for the outcomesimportant to the person.

Support and education for selfmanagement is another key domain ofperson-centred care for people with longterm conditions. We found that there is alack of good indicators for this domainand therefore, with some reluctance,excluded it from our analysis.Main data sourcesThe National Health Service (NHS)Reports from people using NHS servicesare widely and systematically gatheredthrough the national surveys of patientexperience. These include a range ofsurveys — some annually, some at longerintervals — commissioned by governmentthrough the system regulator, the CareQuality Commission (CQC), with thestatus of official national statistics.These patient surveys are carriedout in single service settings (e.g.hospital inpatients). They are in effectmandatory, so that all such NHS servicesmust complete them. They have aperformance management function inthat the regulator makes use of them inI can plan my care withpeople who understand meand my carer(s), allow mecontrol, and bring togetherservices to achieve theoutcomes important to me.‘Narrative for person-centredcoordinated care: summarystatement’, National Voices andThink Local Act Personal, 20131assessments, and Boards are expected touse them for quality improvement.Other recognised national patientsurveys are commissioned by NHSEngland, including: a regular GeneralPractice Patient Survey commissionedvia Ipsos Mori; and occasional nationalsurveys of patients in hospital cancerdepartments and of bereaved relatives,responding to questions about their lovedones’ experience of end of life care (theVOICES survey).Adult social careReports from people using adult socialcare and support are gathered in aslightly different way. The Personal SocialServices Adult Social Care Survey1is carried out via local authoritiesresponsible for social care, andcoordinated by NHS Digital (The Healthand Social Care Information Centre).Other surveys of people’s experienceof social care are available, but usuallyprovide limited samples that do notrepresent all geographical areas or allauthorities.In general, the social care surveys areused to create a ‘consumer’ feedbackfunction but are not used in performancemanagement.For this report, we have looked beyondthese user surveys to see what otherindicators can help to fill out thesnapshot. These include: Thematic reviews by the CQC whichhave investigated some particulartypes of care across service settings(such as end of life care). Surveys by National Voices’ membercharities which touch on aspects ofperson-centred care for people withparticular conditions or groups ofconditions.To be referred to hereafter as the Adult Social Care Survey13

The National Audit of IntermediateCare, organised by an alliance ofRoyal Colleges, the British GeriatricSociety and others, which includemeasures of service user experience. The Personal Budgets OutcomeEvaluation Tool (POET) survey ofpersonal budget holders in social care. The State of Caring 2017, a survey ofcarers by Carers UK. Other types of indicator (not personreported) that might show the extentof use of person-centred interventions,such as personal budgets.A full table of these sources is given atAppendix One.ReferencingWhere we quote from these sources wedo not include reference numbers asthese would clutter the report.Where we quote from other sources ofinformation such as previous reportsof this kind, they are included in thenumbered references.14‘People want to be treatedwith dignity and respect.They want their care andsupport to be coordinatedso they only have to telltheir story once. They wantto be treated as individuals— not as a bag of bodyparts or problems. Theywant to talk about theirpriorities; not necessarilyours. They want to knowabout their options andwhat is known of the risks,benefits and consequencesof all reasonable coursesof action that are open tothem. In short, they want tobe supported to feel as incontrol as they would wish.’xvAlf Collins, Clinical Director forPersonalised Care, NHS England

Person-centred careResearch findingsSummaryWe analysed people’s reports of theircare experiences in the followingdomains:1. Information2. Communication3. Involvement in decisions4. Care planning5. Care coordinationThe first three domains are known tocorrelate strongly with high levels ofpatient satisfactionxvi.Care planning and care coordinationhave been less well measured by surveysof people’s experiences. However, bothare known to be highly significant tothe people who make up the moderncaseload for health and social careservices: people with disabilities, longterm conditions (including mental healthconditions), and other forms of higherneed. These groups need care overtime and from multiple services. Wherecare planning and coordination areabsent, outcomes and experiences willbe worse. This was recognised by thecentral inclusion of these elements in thenational cross-system commitment tointegrated care, 2013.The CQC, in its thematic review ofpeople’s involvement in their care, citescare planning, coordination, and theinvolvement of family members (whichwe also examine later in the report) asthe three biggest enablers that requireimprovement.Note on the reporting of findingsNHS patient survey questions typicallyoffer people response options framed asa strong positive, a partial positive and anegative. For example:‘Yes, definitely’‘Yes, to some extent’‘No’In this report, we are interested in whetherperson-centred care is definitely beingachieved. This is more meaningful andoffers more definitional clarity than‘partial’ positive responses, and it isconsistent with the level of ambition setout in national policy. Hence, we look forthe ‘strong positive’ rather than the ‘partialpositive’ responses.15

1.InformationWhy it is importantPeople cannot act on their health, orhealth-related issues in their lives, withoutinformation. Health literacy — the abilityto use information for health-relateddecisions — is a key factor in populationhealth, since those with the lowest healthliteracy experience the greatest burdenof disease.Many people struggle to understandinformation they are given about theircondition or medications: between 43%and 61% of English adults do not routinelyunderstand information for healthxvii.National patient surveys ask peopleabout information they received whilein a particular service setting, andrelating to their condition, treatment orprocedures.National Health ServiceIn mainstream NHS settings, there arehigh scores for providing people withinformation about specific treatments,often with three quarters or more ofpatients responding positively. Forexample: 76% of inpatients who had anoperation or procedure (2016) saidthat what would happen duringtheir operation was ‘completely’explained; 59% said that they were toldabout how they could expect to feelafterwards. 75% of inpatients had the purposeof any medications to take at homecompletely explained to them. 81% of primary care patients (2017)said their GP was good at explainingtests and treatments.16However, in some services for specificgroups of patients, scores were lower: 62% of women using maternityservices (2015) said that they werealways given the information andexplanations they needed during theirpostnatal care; almost one in 10 saidthey did not receive information. 54% of people using communitymental health services (2016) andwho had started a new medicine inthe past 12 months said they couldcompletely understand the informationthey were given about it; with 12%saying they could not understand theinformation at all.And there is plenty of room forimprovement more generally. Forexample, among inpatients (2016): One quarter (24%) of those admittedvia A&E said they were given noinformation, or not enough, about theircondition or treatment. One third did not receive any writtenor printed information about what theyshould do after leaving hospital. Only 38% of those taking medicines24%One quarter (24%) of those admittedvia A&E said they were given noinformation, or not enough, about theircondition or treatment.

home said they were given a completeexplanation of any side effects towatch out for.Adult social careIn adult social care the focus is more onhow people discover information aboutservices that might be useful to them. Only 20% of respondents to the AdultSocial Care Survey (2015-16) said itwas easy to find information aboutsupport services or benefits, withanother 33% saying it was ‘fairly easy’. Only around a quarter of peopleusing personal budgets said thatthe information they had to makedecisions about their support was ‘verygood’.2.CommunicationWhy it is importantThe most important way in whichinformation is transmitted and tailored tothe individual is often in communicationwith staff and professionals.In many respects, and from the point ofview of service users, healthcare is thiscommunication. We do not talk about‘using primary care services’, but about‘seeing the doctor’.The national patient surveys ask variousquestions on communication, not all ofwhich can be incorporated in this report.We have focused on active listening andexplaining things clearly, as these areparticularly indicative of professionalshaving the right skills and behaviours forperson-centred care.2.aActive listeningIn a number of settings, more than threequarters of respondents said that theirhealthcare professionals demonstratedgood listening skills. For example: 78% of children and young people feltthat staff in hospital listened to them(2015). 80% of women who had usedmaternity services (2015) felt thatmidwives always listened to them inantenatal consultations, and 77% inpostnatal consultations. 77% of A&E patients (2014) said thatdoctors and nurses definitely listenedto what they said. 70% of people who used communitymental health services (2016) said theperson they had seen most recentlyhad listened carefully to them. 87% of general practice patients(2017) said their GP was good atlistening to them.However, these overall reports can masksome anxieties and deficiencies. Withinthe general practice figure, for example,only around half of patients said the GPwas ‘very good’ at listening as opposedto ‘fairly good’.Healthwatch England’s report on people’sexperiences of primary care (2015) foundthat communication was a key area ofconcern, with people reporting that theirGP does not always listen fully, or believewhat they have to say. This can lead tosome groups not reporting symptoms orissues such as depression.Although these scores for listeningonce the person is in contact witha staff member are relatively high, arelated question is the extent to whichpatients have the opportunity and time17

for discussions about things that areworrying them.Among adult hospital inpatients (2016),for example:Here, the scores are weaker: 70% said that if they had an importantquestion to ask a doctor, this wasanswered in a way they couldunderstand. 46% of primary care patients (2017)said the GP was ‘very good’ at makingenough time for them. 24% of inpatients (2016) said that staffwere not always available to them ifthey had worries or fears. 59% of inpatients said they ‘always’received enough emotional supportfrom staff. 28% of A&E patients (2014) could notanswer ‘yes, definitely’ when asked ifthey had enough time to discuss ahealth or medical problem. 55% of A&E patients said ‘yes,completely’ when asked whether, ifthey had anxieties or fears about theircondition or treatment, a doctor ornurse discussed them (with 15% sayingno). 63% of people who used communitymental health services (2016) saidthey definitely had enough time todiscuss their needs and treatment(with 11% saying no). 29% of bereaved relatives in theVOICES survey (2015) strongly agreedthat their loved one’s emotional needswere met near the end of life.2.b Explaining in a way that peoplecan understandPatients treated in hospital report thattheir health and care professionals arevery good at explaining their condition,treatment, or medications in a way theycan understand.18 76% said that what would happenduring their operation was ‘completely’explained. 83% said they had been given acomplete explanation of the risksand benefits of their operation orprocedure in a way they couldunderstand.Among children treated in hospital(2014): 82% said they were spoken to in a waythey could understand.Strong results are reported in specifichospital departments: 83% of cancer patients (2015) whoreceived more than one treatmentsaid that these were explainedcompletely before they started; 73%said that side effects were explained ina way they could understand. 78% of people who had been inA&E departments (2014) said that amember of staff explained any teststhey needed in a way they understood. 89% of women who had usedmaternity services (2015) reportedthat they were always spoken to in away they could understand duringantenatal appointments.For those surveys that are repeatedregularly over time, trend data suggeststhat many of the results for informationprovision and for communication withstaff improved over the decade from 2005to 2015xviii.

3.Involvement in decisionsWhy it is importantThe provision of information, and goodcommunication between people and thestaff and professionals they encounter,should provide a basis for people tobe as involved as they want to be indecisions about their health, care andtreatment.Involvement in decisions is a centralelement in any definition of personcentred healthcare, and is stronglycorrelated to people’s satisfaction withtheir care, treatment and support.National Health ServiceIn hospital settings, the results for people’sinvolvement in decisions are markedlylower than those for communicationabout specific tests, treatments andprocedures: 56% of inpatients (2016) said they weredefinitely as involved as they wanted tobe in decisions about treatments. 55% of inpatients said they weredefinitely as involved as they wanted tobe in decisions about discharge (with15% saying they were not involved). 57% of children and young peopletreated in hospital (2014) said theywere as involved as they wanted to bein decisions about their care (with 13%saying they were no

This data can be found — in patches — in surveys of patients and service users. There have been previous attempts at this task, in reports from Picker Institute Europe [2007]vi, The King's Fund/Picker Institute Europe [2015]vii and The Health Foundation [2015]viii. These looked just at the NHS, through the lens of national patient surveys.