Transcription

MANAGEMENTS T R AT E G YMEASUREMENTM A N AG E M E N T AC C O U N T I N G G U I D E L I N EImpacting FutureValue: How toManage yourIntellectual CapitalByBernard MarrPublished by The Society of Management Accountants of Canada, the AmericanInstitute of Certified Public Accountants and The Chartered Institute ofManagement Accountants.

N OT I C E TO R E A D E R SThe material contained in the Management Accounting Guideline Impacting Future Value: How to Manage your Intellectual Capitalis designed to provide illustrative information with respect to the subject matter covered. It does not establish standards orpreferred practices.This material has not been considered or acted upon by any senior or technical committees or the board ofdirectors of either the AICPA, CIMA or CMA Canada and does not represent an official opinion or position of either the AICPA,CIMA or CMA Canada.Copyright 2008 by The Society of Management Accountants of Canada (CMA Canada), the American Institute of CertifiedPublic Accountants, Inc. (AICPA) and The Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA). All Rights Reserved.No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, withoutthe prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright).For an Access Copyright Licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1 800 893 5777.ISBN: 1-55302-220-3

MANAGEMENTIMPACTING FUTURE VALUE:HOW TO MANAGE YOUR INTELLECTUAL CAPITALINTRODUCTIONGrowth, above-average earnings, andsustainable competitive advantages areno longer driven by investing in physicalassets such as factories, offices, ormachinery, but instead by investing in andmanaging intellectual capital.The successof leading companies such as Amazon,Google, Microsoft, and Wal-Mart isbased on their intellectual capital. Physicalassets such as distribution warehouses,office buildings, and stores are important,but not as much as (for example) knowledge about customers, technology, andmarkets. For example, organizationssuch as Wal-Mart, with its huge storeinfrastructure, couldn’t perform as wellas it does without (a) the intelligenceto build its stores at the right locations,(b) the knowledge about consumersto stock the right goods, and (c) itsexpertise in inventory replenishment.Intellectual capital allows organizations toCONTENTSEXECUTIVE SUMMARYIntellectual capital helps to drive successand create value.Although physical andfinancial assets remain important,intellectual capital elements such as theright skills and knowledge, a respectedbrand and a good corporate reputation,strong relationships with key suppliers,the possession of customer and marketdata, or a culture of innovation setenterprises apart.PageINTRODUCTIONABOUT THIS MAGWHAT IS INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL?Defining Intellectual CapitalFIVE STEPS TO SUCCESSFULINTELLECTUAL CAPITAL MANAGEMENT1. Identifying your Intellectual Capital2. Mapping the IntellectualCapital Value Drivers3. Measuring Intellectual Capital4. Managing Intellectual Capital5. Reporting Intellectual CapitalCONCLUSIONUSEFUL WEBSITESREFERENCES AND ENDNOTES34557710142427292930Success and future value creation in today’seconomy depend on the ownership andappropriate management of intellectual capital.Superior performance is no longer driven bytraditional physical assets, but instead primarily byintellectual capital.That term includes knowledge,skills, brands, corporate reputation, relationships,information and data, as well as processes, patents,trust, or an innovative organizational culture.The importance of intellectual capital as anenabler of future performance is now generallyaccepted among executives across the world.Most organizations, however, still lack practicalskills, tools, and techniques to identify, measure,and manage this vital performance driver.Thismanagement accounting guideline (MAG)addresses this lack by introducing five key stepsfor successfully managing intellectual capital,namely: (1) how to identify intellectual capital inyour organization, (2) how to map its impact,(3) how to measure it, (4) how to manage it, and(5) how to report it. Practical and easy-to-applytools and techniques are provided for each ofthese steps, to equip managers and accountantswith the necessary skills to successfully managethe intellectual capital of their organizations.3

MANAGEMENTS T R AT E G YMEASUREMENTleverage their tangible resources.Withoutappropriate intellectual capital, physical assets arejust commodities that can yield, at best, averagereturns.1 Identifying and managing the rightintellectual capital is and will increasingly be thekey differentiator between successful, mediocre,and failing enterprises.It is therefore not surprising that intellectualcapital has moved from the periphery to the coreof modern businesses. Organizations that want toremain competitive in today’s world need toolsand techniques to manage their intellectualcapital. In fact, executives around the world haveconfirmed this in a recent survey by Accentureand the Economist Intelligence Unit, which foundthat most executives believe that intellectualcapital is absolutely critical for the future successof their businesses.2 The same survey also findsthat most executives agree that their currentapproaches to measuring and managing intellectualcapital are either poor or non-existent. Otherrecent surveys, including one that surveyed780 Chief Executive Officers and Chief FinancialOfficers of the 5,000 largest companies in theUnited States, and another involving 15 of theworld’s leading banks and financial services firms,found that measuring and managing intangiblesis the least developed in current performancemeasurement and management systems.3 A reportfrom the Brookings Institution, an independentresearch and policy institute, outlined that thelarge and growing discrepancy between (a) theimportance of intangible assets to economicgrowth, and (b) our inability to clearly identify,measure, and account for those assets is a seriousproblem for business managers, investors, andgovernments.4 Also, Intellectual capital is notonly critical for commercial enterprises, butincreasingly it matters as well in government andnot-for-profit organizations. Studies in governmentorganizations have found that intangibles suchas corporate reputation, human capital, andrelationships with key stakeholders are of vitalimportance.5The internal problem of identifying, measuring,and managing intellectual capital also applies toexternal reporting, where there are growingfrustrations with the inability of traditionalfinancial reporting to account for and report onintangibles.The increasing gap between (a) whatorganizations report in their annual reports(mainly traditional physical and financial assets),and (b) what actually matters the most (theintangibles) is reflected in the ever increasingvariance between book value (mainly traditionalassets or liabilities recorded in the balance sheet)4and market value (the value of a public companyas measured by the share price times the numberof shares issued).To positively impact future value, organizationsrequire a better understanding of intellectualcapital and the latest tools available to identify,measure, and manage this important value driver.This MAG provides such understanding and outlines the latest tools that will equip managers andaccountants with the necessary skills to bettermanage intangibles to improve organizationalperformance and drive future value. In addition,this MAG looks at the latest tools for externalreporting of intellectual capital, to improve theexternal communication of the company’s valueto its shareholders and stakeholders.ABOUT THIS MAGThis guideline is aimed at finance professionals andaccountants in business who would like to betterunderstand how to manage intellectual capital. Inparticular, it is for those who are responsible forimplementing or improving the management,measurement, and reporting of intellectual capitalin their organizations. It will also be useful toanyone looking for a general introduction andan overview of the key ideas and challenges ofmeasuring, managing, and reporting intangibles.This guideline follows on from the CIMA report‘Understanding Corporate Value: Managing andReporting Intellectual Capital,’ published in 20036.This earlier technical report provided an overviewof tools and approaches for managing andreporting intellectual capital. However, the worldhas moved on since 2003, and new tools andstandards have emerged. Also, this MAG providesclearer guidance and practical tools to enable thereader to better measure, manage, and reportintellectual capital.This MAG outlines five key steps for successfullymanaging intellectual capital. Each step containsa number of practical and easy-to-follow toolsand techniques. Although all of these tools andtechniques are rigorously grounded in the latestresearch, they have been selected because of theirpractical relevance and easy application.The firststep looks at how to identify intellectual capitalwithin an organization. Step two provides tools forassessing the strategic value of intellectual capitalby visually mapping how it helps organizations toaccomplish their strategic objectives. Step threediscusses how to measure intellectual capital andprovides tools and techniques to do so. Step fouroutlines how to use the resultant information tobetter manage intellectual capital in organizations.

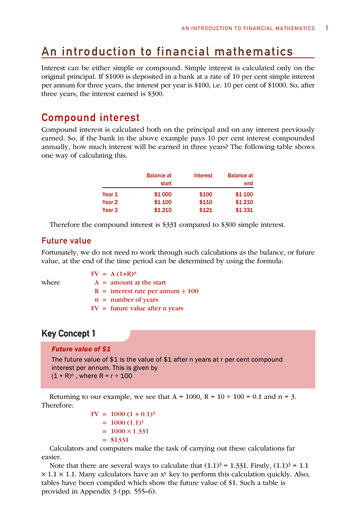

I M PA C T I N G F U T U R E VA L U E :H O W T O M A N A G E YO U R I N T E L L E C T U A L C A P I TA LIt explores how to improve decision making,how to review the strategy, and how to assess therisks associated with intellectual capital.The finalstep discusses the reporting and disclosure ofintellectual capital, and provides guidance on howto prepare such reports. Before discussing each ofthe five intellectual capital management steps, weprovide a detailed definition of what intellectualcapital is – to dispel a lot of confusion about themeaning of this term.used as a template to ensure that all possibleintangibles are identified. Debates about apotential overlap, or whether one intangibleshould be put into one category or another,are therefore, at this point, not productive orparticularly useful.What is important is thatwe identify all intangibles that matter to ourorganizations.WHAT IS INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL?7Together with physical and financial capital,intellectual capital is one of the three vitalresources of organizations. Intellectual capitalincludes all non-tangible resources that (a) areattributed to an organization, and (b) contributeto the delivery of the organization’s valueproposition. Intangible resources can be splitinto three components: human capital, structuralcapital, and relational capital (see Figure 1). Eachof these is discussed further below.Before we can identify, measure, manage, andreport on intellectual capital, we need to understand what we mean by that term.The conceptof intellectual capital is often discussed, but notalways well defined.8 And a multitude of differentwords have been used to describe the same or asimilar concept. People tend to use terms suchas assets, resources, or performance drivers; andthey often replace intellectual with words such asintangible, knowledge-based, or non-financial. Anyof these words (or a combination of them) canbe found in the management literature. Also,some disciplines (such as the financial accountingand legal disciplines) have created quite narrowdefinitions, such as ‘non-financial fixed assets thatdo not have physical substance but are identifiableand controlled by the entity through custody andlegal rights,’ the definition found in accountingstandards. Although narrow definitions like thisare necessary to ensure consistency in balancesheets and other external reports, they are lessuseful in creating a broader understanding ofintellectual capital.This is so because they excludemany commonly accepted intangibles, such ascustomer relationships or knowledge and skillsof employees, as they cannot be controlled bythe firm in an ‘accounting’ sense. All of this hasled to some considerable confusion about whatintellectual capital is and is not.In this guideline, we will use the terms ‘intellectualcapital’ and ‘intangibles’ interchangeably. It isimportant to stress that there is no generally rightor wrong way to classify intellectual capital. Forthe purpose of this guideline, it is important toprovide as broad a classification as possible, toensure that the reader gets a complete pictureof what intellectual capital encompasses.The keyobjective of this broad classification (definedbelow) is to increase the general understandingof what intellectual capital is, and therefore tofacilitate the identification of intellectual capitalwithin organizations.The classification should beDefining Intellectual CapitalHuman CapitalThe principal sub-components of an organization’shuman capital are its workforce’s skill sets, depthof expertise, and breadth of experience. Humanresources can be thought of as the living andthinking part of intellectual capital resources.9These can therefore walk out at night whenpeople leave; relational and structural capital onthe other hand remains with the organizationeven after people have left. Human capital includesthe (a) skills and competencies of employees,(b) their know-how in certain fields that areimportant to the success of the enterprise, and(c) their aptitudes and attitudes. Employee loyalty,motivation, and flexibility will often be significantfactors too, because a firm’s ‘expertise andexperience pool’ is developed over time. A highlevel of staff turnover may mean that a firm islosing these important elements of intellectualcapital.Relational CapitalRelational capital includes all the relationshipsthat exist between an organization and anyoutside person or organization.These can includecustomers, intermediaries, employees, suppliers,alliance partners, regulators, pressure groups,communities, creditors, and investors. Relationships tend to fall into two categories – those thatare formalized through, for example, contractualobligations with major customers, suppliers andpartners, and those that are more informal.5

MANAGEMENTS T R AT E G YFigure 1: Classification of Intellectual ntellectualCapitalHuman Capital Knowledge and skillsWork-related experienceCompetenciesVocational qualificationEmployee engagementEmotional intelligenceEntrepreneurial spiritFlexibilityEmployee loyaltyEmployee satisfactionEducationCreativity Relational CapitalStructural CapitalFormal relationshipsInformal relationshipsSocial networksPartnershipsAlliancesBrand imageTrustCorporate reputationCustomer loyaltyCustomer engagementLicensing agreementsDistribution agreementsJoint ventures Organizational culture Corporate values Social capital Management philosophyAlthough the former tended to be predominant inthe past, today, the latter have a more importantimpact on how the enterprise is managed. Intoday’s integrated economy, with just-in-timesupply chains, relationships with trading partnersand suppliers can be crucial. Brand image,corporate reputation, and product/servicereputation, which reflect the relationshipsbetween organizations and their (current andpotential) customers, also fall into this category.Structural CapitalStructural capital covers a broad range of vitalelements. Foremost among these are usually(a) the organization’s essential operatingprocesses, (b) how it is structured, (c) its policies,information flows, and content of its databases,(d) its leadership and management style, and(e) its culture, and (f) its incentive schemes.Theycan, however, also include legally protectedintangible resources. Structural capital can besub-categorized into Culture, Practices and Routines,and Intellectual Property.Organizational culture is fundamental to achievingorganizational goals. Organizational cultureprovides a common way of seeing things, sets thedecision-making pattern, and establishes the valuesystem.10 Cultural resources include corporate6 Processes and routines Formal processes Tacit / informal routines Management processes Intellectual property Brand names Data and information Codified knowledge Patents / copyrights Trade secretsculture, organizational values, and managementphilosophies.They provide employees with ashared framework to interpret events, a framework that encourages individuals to operate bothautonomously and as a team to achieve thecompany’s objectives.11Processes and Routines, which reflect sharedorganizational knowledge, can be importantorganizational resources. Practices and routinesinclude internal practices and processes; thesecan be formal or informal (tacit) procedures andrules. Formalized routines can be reflected inprocess manuals that provide codified proceduresand rules; informal routines include understood(but unstated) codes of behavior and workflows.One example of a process that has become avaluable strategic resource is Southwest Airlines’airplane turnaround, which they have optimizedto only last 25 minutes.This process, introduced asa necessary part of Southwest’s start-up asa low-cost carrier, has today become a keydifferentiator.12Intellectual property – owned or legally protectedintangible resources – is becoming increasinglyimportant. Patents, copyrights, trademarks, brands,registered designs, trade secrets, database content,and processes whose ownership is granted to thecompany by law have become a key element of

I M PA C T I N G F U T U R E VA L U E :H O W T O M A N A G E YO U R I N T E L L E C T U A L C A P I TA Lcompetition.13 Intellectual property is owned bythe organization and not its employees. Itrepresents the tools and enablers that help todefine and differentiate an organization’s uniqueoffering to the markets in which it operates.Examples of intellectual property includetrademark symbols such as the McDonald’sArches and the Nike Swoosh, or the patented‘1-click’ buying option at Amazon.com. Coca-Cola,for example, made a conscious decision to keepthe formula for Coke a trade secret that it activelyprotects. Had they patented the formula instead,their patent protection would have run out manyyears ago, most likely destroying its market share.FIVE STEPS TO SUCCESSFULINTELLECTUAL CAPITALMANAGEMENTIn this MAG, we will outline five key steps forsuccessfully managing intellectual capital (seeFigure 2).The first step is to identify anorganization’s intellectual capital. Once this isknown, we need to assess its value. It is importantto understand that not all intellectual capital isautomatically valuable to an organization. It is onlyvaluable if it helps to deliver the organizationalobjectives. In step two, we therefore assess therelevance of intellectual capital by mapping thestrategy (with its intellectual value drivers) ontoa strategic map.The third step is to extractmeaningful management information frommeasuring the performance of intellectual capital.In step four, this management information canthen be used to analyze performance and todevelop management insights that informorganizational decision making and learning. Finally,in step five, external reports can be produced tocommunicate the value of intellectual capital tointernal and external stakeholders.Figure 2: Five-Step Intellectual CapitalManagement Model1. Identifing your intellectual capital2. Mapping the key value driversEach of these five steps will be discussed in detailbelow.We will explain what each step involves,and provide a number of tools and techniquesdesigned to help the practicing manager to bettermanage the organization’s intellectual capital.1. Identifying your Intellectual CapitalThe first step, an inventory check, requiresidentifying an organization’s intellectual capital.The categorization of intellectual capital outlinedabove can be used to facilitate a discussion aboutthe current stock of intangibles. It can be used tocreate a template that informs people about thedifferent categories of intellectual capital, andprompts them to think about their organizations’different types of intangibles (see Figure 3).Intellectual capital can be identified throughconducting interviews, facilitated workshops, orvia mail or online surveys. From experience,face-to-face individual interviews or surveys workbest, as they allow everyone to have a say, free ofthe suppressing influence of stronger or moredominant participants in workshops.It is important to emphasize again that theobjective of this classification template is tofacilitate a discussion about as many differentresources (intellectual, physical, and financialcapital) as possible, to create the most realisticpicture of the existing resource architecture.Individual responses from surveys or interviewscan then be analyzed and compiled into a list of allthe major resources. At this point, it is no longeras important to use the categories introduced inFigure 1, as it is to present the individual resourcesin a language that is understood within theparticular organization. Different organizationstend to use organization-specific terminology todescribe the same resources. It is always advisableto use the organization’s commonly used languageinstead of the categories or examples provided inthe template below. Using terminology such as‘human capital’, for example, can cause misunderstanding or even cynicism, especially if thisterminology is not commonly used within theorganization.Intellectual Capital Underpins Competencies3. Measuring intellectual capital4. Managing intellectual capital5. Reporting intellectual capitalEven though most organizations possess a widevariety of intellectual capital, some will contributemore to delivery of their value proposition thanothers.This is because (a) the value of intellectualcapital depends on an organization’s specificstrategy, and (b) intellectual capital dynamicallyinteracts with and depends on other resources:7

MANAGEMENTS T R AT E G YMEASUREMENTFigure 3: Identifying Your Resource Stock (Source Marr, 2008)Resource CategoryExamples of Sub-categories:Human CapitalKnowlege, education, technical knowledge andexpertise, skills, know-how, attitudes, experience,motivation, flexibility, commitment, creativity, etc.Relational CapitalCustomer relationships, supplier relationships,reputation, image, trust, contractual relationships,informal relationships, alliances, relationships withregulators, partners, etc.Structural CapitalProcesses, tacit routines, organizational structure,governance and management approaches,organizational culture, social capital, shared identity,patents, brand names, copyrights, trade secrets,codified information and knowledge, e.g., indatabases or process manuals, etc.Physical CapitalProperty, plants, location of buildings, informationand communication infrastructure, machines,equipment, natural resources, physical infrastructure,office design, etc.Financial CapitalCash, investments, bonds, loans, budget, etc. The value of intellectual capital depends onan organization’s specific strategy. Forexample, the know-how of building enginesis essential for Honda, but of little value to afinancial services firm; likewise, the competencies associated with creating light anddurable composite materials so essential forsuccessful Formula One motor racing teamsis undoubtedly probably of little value to atelecommunications firm. Intellectual Capital elements are not static –they dynamically interact with each other,and often depend on other resources fortheir value. For example, Amazon.com’s brandawareness and reputation, although criticallyimportant, would rapidly fade without itsefficient distribution network, well-designedinternal processes, and strong supplier relationships. It is therefore impossible to value a brandname without taking into account all otherimportant factors, such as reputation, people,processes, etc. Cases such as the accountingfirm, Arthur Andersen, have shown how abrand name can disappear overnight if thesupporting intangibles such as trust orreputation fall away. Often referred to as theinterconnectedness of resource stocks, suchrelationships are extremely important tointangibles.This means, therefore, that individual intellectualcapital resources interrelate with other intangibleand tangible resources to form core competencies.8Intellectual Capital elements with asignificant presence in our organization:In turn, these allow an organization to perform itscore activities to deliver its value proposition andstrategic deliverables (see Figure 4). A coreactivity is an excellently performed internalactivity that is central, not peripheral, to acompany’s strategy, competitiveness, and valueproposition. An organization should only havevery few (usually between 2 and 5) core activities.Figure 4: Intellectual CapitalUnderpins Capabilities andCore CompetenciesValue Proposition /Strategic ntangible and tangible)

I M PA C T I N G F U T U R E VA L U E :H O W T O M A N A G E YO U R I N T E L L E C T U A L C A P I TA LFigure 5: Assessing the Importance of Intellectual CapitalIdentified KeyResources ExamplesRelative strengths of these resourcesin our organization0 not at all important10 vitally importantRelative importance of these resourcesto delivering our value proposition0 not at all important10 vitally importantOur specific subjectknowledge710Our perceivedreputation49Relationships withkey partners46Our patent for X92Our brand X87Etc.To understand the role and strategic importanceof intellectual capital in any organization thereforerequires a clear understanding of the firm’sstrategic direction and objectives.Assessing the Strategic Value of IntellectualCapitalThe relative importance or strategic value ofintellectual capital can only be assessed in thecontext of the existing organization.The questionsto ask are: How important are our differentintellectual capital resources to achieving ouroverall value proposition? Or, how strong are ourexisting resources and how can we utilize themmore effectively? Independently assessing (a) theimportance of the different resources to deliveryof your value proposition, and (b) your resourcestrengths allows organizations to perform a gapanalysis.This lets you understand whether youare building the appropriate intellectual capitalfor your value proposition, or whether you areunder- or over-investing in certain areas.This assessment is best done individually, eitherin interviews or by survey. Or it can be done ina workshop setting.The easiest way to performthe assessment is to use the list of key resourcesidentified above, and then to add columns toassess the relative strengths and the importanceof these resources to delivering the currentstrategy (see Figure 5). Conducting both assessments allows organizations to highlight any gaps.The results from the individual assessments canthen be aggregated and displayed in a resourcemap. Such a map visually represents the relativestrength or importance of the different resources(intangible and tangible). It is also possible toinclude the two data sets (strengths and importance), and to use different size bubbles toindicate any gaps.Figure 6 illustrates such a resource map, onecreated for a leading online retailing business14to understand the relative importance of itsresources to deliver the existing value proposition.The value proposition of this well-known retailerwas to become the world’s preferred source for aparticular type of goods by providing consumersnot only with top level service, but also highquality value-added information, excellent price,simple transactions, and an enjoyable shoppingexperience. In this example, managers assessedstructural capital and human capital as the mostimportant intellectual capital value drivers(indicated by the biggest bubbles).This commercialenterprise places particular emphasis on itsknowledge of the market and its customers, plus itsprocesses and brand. Other important resourceswere its relationships, especially with its suppliersand lenders, as the business is still in the growingphase and unprofitable.This map helped theorganization to understand the relative importanceof its intellectual capital in order to allocate itsresources appropriately.As discussed in Figure 6, intellectual capitalinteracts with other resources to create a corecompetency, which in turn helps to deliver thevalue proposition.This means that resourceinterdependencies can only be assessed in relationto the organization’s existing core competenciesand value proposition. If you have defined yourstrategic deliverables and core activities, you canthen use the above resource list to understandhow the resources combine to deliver your corecompetencies and value proposition.159

MANAGEMENTS T R AT E G YMEASUREMENTFigure 6: Visualizing the Relative Importance of Key Resources(Source Marr, 2006)Organizational Key ResourcesPhysical CapitalRelational l ipsDistributionKnow HowBrandProcessDesignKnow HowProcessesPatentsMarketingKnow HowHuman CapitalStudies have found that organizational resources(especially intangibles) are interdependent andenhance each other in affecting organizationalperformance. For example, a strong brand namemight improve performance, but a strong brandname combined with the right market knowledgeand customer service processes can improveperformance even more. As a consequence,organizations should attempt not only to(a) understand the direct effect of each organizational resource on performance, but also to(b) assess the interdependencies and their effectson performance.16 For this purpose, you can usea matrix to rate how resource A depen

INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL MANAGEMENT 7 1. Identifying your Intellectual Capital 7 2. Mapping the Intellectual Capital Value Drivers 10 3. Measuring Intellectual Capital 14 4. Managing Intellectual Capital 24 5. Reporting Intellectual Capital 27 CONCLUSION 29 USEFUL WEBSITES 29 REFERENCES AND ENDNOTES 30 Page 3 MANAGEMENT