Transcription

Na t i o n a l Hi g h Bl o o d Pre s s u re Ed u c a t i o n Pro g ra mPrimary Preventionof Hypertension:Clinical and Public HealthAdvisory from the NationalHigh Blood PressureEducation ProgramU.S.DEPARTMENTN A T I O N A LN A T I O N A LH E A R T ,OFH E A LT HANDI N S T I T U T E SL U N G ,A N DHUMANO FSERVICESH E A L T HB L O O DI N S T I T U T E

Primary Preventionof Hypertension:Clinical and Public HealthAdvisory from the NationalHigh Blood PressureEducation ProgramNational Institutesof HealthNational Heart, Lung,and Blood InstituteNational High Blood PressureEducation ProgramNIH P U B L I C AT I O NN O . 02-5076N O V E M B E R 2002

ContentsPRIMARY PREVENTION OF HYPERTENSION CLINICAL AND PUBLIC HEALTH ADVISORYFROM THE NATIONAL HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE EDUCATION PROGRAMThe Working GroupivTHE NATIONAL HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE EDUCATION PROGRAM COORDINATINGCOMMITTEE MEMBER ORGANIZATIONSvFOREWORDviBACKGROUNDMethod of guideline development11Evidence of classifications2LIFETIME BURDEN OF ELEVATED BLOOD PRESSURE3APPROACHES TO PRIMARY PREVENTION OF HYPERTENSIONPopulation-based strategy44Intensive targeted strategy4Weight loss66Dietary sodium reduction6Increased physical activity8Moderation of alcohol consumption8Potassium supplementation8Modification of whole diets8INTERVENTIONS WITH DOCUMENTED EFFICACYCalcium supplementation1010Fish oil supplementation10Herbal or botanical dietary supplements10INTERVENTIONS WITH UNCERTAIN OR LESS PROVEN EFFICACYPRIMARY PREVENTION IN CHILDREN11ADDITIONAL RESEARCH12BARRIERS TO IMPROVEMENT13SUMMARY14REFERENCES15

PRIMARY PREVENTION OF HYPERTENSION CLINICAL AND PUBLIC HEALTH ADVISORYFROM THE NATIONAL HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE EDUCATION PROGRAMThe Working GroupCOCHAIRPaul K. Whelton, M.D., M.Sc.Senior Vice President for Health SciencesProfessor of Epidemiology and MedicineTulane University Health Sciences CenterNew Orleans, LACOCHAIRJiang He, M.D., Ph.D.Associate Professor of Epidemiologyand MedicineDepartment of EpidemiologyTulane UniversitySchool of Public Health and Tropical MedicineNew Orleans, LALawrence J. Appel, M.D., M.P.H.Professor of MedicineEpidemiology and International HealthJohns Hopkins Medical InstitutionsBaltimore, MDJeffrey A. Cutler, M.D., M.P.H.Senior Scientific AdvisorDivision of Epidemiologyand Clinical ApplicationsNational Heart, Lung, and Blood InstituteNational Institutes of HealthBethesda, MDStephen Havas, M.D., M.P.H., M.S.ProfessorDepartment of Epidemiology andPreventive MedicineUniversity of Maryland School of MedicineBaltimore, MDivTheodore A. Kotchen, M.D.Professor of MedicineAssociate Dean for Clinical ResearchMedical College of WisconsinMilwaukee, WIEdward J. Roccella, Ph.D., M.P.H.CoordinatorNational High Blood PressureEducation ProgramOffice of Prevention, Education, and ControlNational Heart, Lung, and Blood InstituteNational Institutes of HealthBethesda, MDRon Stout, M.D., M.P.H.Associate Director, Medical, Health CareThe Procter and Gamble CompanyHealth Care Research CenterMason, OHCarlos Vallbona, M.D.Distinguished Service ProfessorDepartment of Family andCommunity MedicineBaylor College of MedicineHouston, TXMary C. Winston, Ed.D., R.D.Senior Science ConsultantAmerican Heart AssociationDallas, TXSTAFFJoanne Karimbakas, M.S., R.D.National High Blood PressureEducation Program Partnership LeaderAmerican Institutes for ResearchProspect CenterSilver Spring, MD

THE NATIONAL HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE EDUCATION PROGRAMCOORDINATING COMMITTEE MEMBER ORGANIZATIONSThe NHBPEP Coordinating Committee includes representatives from the following member organizations:American Academy of Family PhysiciansAmerican Society of Health-System PharmacistsAmerican Academy of Insurance MedicineAmerican Society of HypertensionAmerican Academy of NeurologyAssociation of Black CardiologistsAmerican Academy of OphthalmologyCitizens for Public Action on High BloodPressure and Cholesterol, Inc.American Academy of Physician AssistantsAmerican Association of OccupationalHealth NursesInternational Society on Hypertension in BlacksNational Black Nurses Association, Inc.American College of CardiologyNational Hypertension Association, Inc.American College of Chest PhysiciansNational Kidney Foundation, Inc.American College of Occupationaland Environmental MedicineNational Medical AssociationNational Optometric AssociationAmerican College of Physicians—American Society of Internal MedicineNational Stroke AssociationAmerican College of Preventive MedicineNHLBI Ad Hoc Committee onMinority PopulationsAmerican Dental AssociationAmerican Diabetes AssociationAmerican Dietetic AssociationAmerican Heart AssociationAmerican Hospital AssociationAmerican Medical AssociationAmerican Nurses AssociationAmerican Optometric AssociationSociety of Geriatric CardiologySociety for Nutrition EducationFederal Agencies:Agency for Healthcare Research and QualityCenters for Medicare and Medicaid ServicesDepartment of Veterans AffairsHealth Resources and Services AdministrationAmerican Osteopathic AssociationNational Center for Health Statistics, Centers forDisease Control and PreventionAmerican Pharmaceutical AssociationNational Heart, Lung, and Blood InstituteAmerican Podiatric Medical AssociationNational Institute of Diabetes and Digestive andKidney DiseasesAmerican Public Health AssociationAmerican Red Crossv

ForewordAs part of its mission to translate research results intopractice, the National High Blood Pressure EducationProgram (NHBPEP) Coordinating Committeedevelops guidelines, advisories, and statements forthe clinical and public health community.Drs. Whelton and He are to be congratulated forcoordinating the efforts of updating the advisory toreflect the latest scientific information on preventingand managing elevated blood pressure, whichremains an important public health imperative.Its first statement on the primary preventionof hypertension was published in 1993. Sincethen, additional evidence supporting those recommendations has emerged.Claude Lenfant, M.D.A distinguished panel reviewed the scientific literature and worked with the NHBPEP CoordinatingCommittee to develop this new advisory, whichupdates the 1993 National High Blood PressureEducation Program Working Group Report on PrimaryPrevention of Hypertension. The new statementrecommends prevention of hypertension throughboth a population-based strategy and an intensivestrategy focused on individuals at high riskfor hypertension.These two strategies are complementary andemphasize six approaches: Engage in moderatephysical activity; maintain normal body weight;limit alcohol consumption; reduce sodium intake;maintain adequate intake of potassium; and consume a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and lowfatdairy products and reduced in saturated and totalfat. Applying these approaches can prevent bloodpressure from rising in the general populationand can lower blood pressure in persons with highnormal blood pressure or hypertension.viDirectorNational Heart, Lung, and Blood InstituteandChairNational High Blood Pressure EducationProgram Coordinating Committee

BackgroundA direct positive relationship between blood pressureand cardiovascular risk has long been recognized.This relationship is strong, continuous, graded,consistent, independent, predictive, and etiologicallysignificant for those with and without coronary heartdisease (CHD);1F,2F it has been identified in bothmen and women, younger and older adults, differentracial and ethnic groups, and different countries;and applies to those with high-normal blood pressureas well as those with hypertension.1F,3FDespite progress in prevention, detection, treatmentand control of high blood pressure, hypertensionremains an important public health problem.Based on the Third National Health and NutritionExamination Survey (NHANES III), approximately43 million noninstitutionalized U.S. adults, 18 yearsof age or older, met the criteria for diagnosis ofhypertension (systolic blood pressure 140 mmHgor diastolic blood pressure 90 mmHg, or takingantihypertensive medication) recommended inThe Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee onPrevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatmentof High Blood Pressure ( JNC VI).4X,5Pr,6X Almost13 million additional persons had been diagnosedas having hypertension by a health care professionalbut did not meet the previously mentioned JNC VIcriteria.6X Approximately 20 million of the estimated 43 million persons with hypertension werenot being treated with antihypertensive medication,and almost 12 million of the nearly 23 million forwhom such medication was being prescribed hadinadequately controlled hypertension.6X More than23 million adults had high-normal blood pressure(130–139 mmHg systolic or 85–89 mmHg1diastolic),and almost38 million hadnormal but above optimalblood pressure levels (120–129mmHg systolic or 80–84 mmHg diastolic).Primary prevention of hypertension provides anopportunity to interrupt and prevent the continuing costly cycle of managing hypertension and itscomplications.7Pr The purpose of this article is toupdate the 1993 National High Blood PressureEducation Program Working Group Report on PrimaryPrevention of Hypertension7Pr and to address thepublic health challenges of hypertension describedin the JNC VI report.5PrMETHOD OF GUIDELINE DEVELOPMENTThe National High Blood Pressure EducationProgram (NHBPEP) Coordinating Committeeconsists of representatives from 38 nationalprofessional, public, and voluntary healthorganizations and seven Federal agencies. As part ofthe mission to translate research results into practice,the NHBPEP Coordinating Committee developsguidelines, advisories, and statements for the clinicaland public health communities. Since the first statement on the primary prevention of hypertensionwas published in 1993,7Pr new and further evidencesupporting those recommendations has emerged.The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute(NHLBI) staff identified research suggesting theneed to update the NHBPEP 1993 report.7 Thechair of the NHBPEP Coordinating Committeeappointed cochairs and additional members to1

serve as a working group on behalf of theCoordinating Committee.To assist the cochairs, NHLBI staff conducted aMEDLINE search of the English-language, peerreviewed scientific literature since 1993 through2002 using key Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)terms hypertension, blood pressure, primary prevention,exercise, weight loss, alcohol drinking, diet sodium-restricted,dietary potassium, and diet.The cochairs reviewed the MEDLINE search results,identified new areas to be addressed, and, with theassistance of NHLBI staff, developed an outlineand subsequently assembled a working draft of thedocument. The draft document was distributed tothe members of the working group for additionsand modifications.Thereafter, the additions and modifications weretabulated and discussed via teleconferencing andelectronic mail. This process continued amongmembers of the working group, NHLBI staff,and cochairs in a reiterative fashion. The cochairsadjudicated differences of opinions. The assembleddocument was mailed to the working group members for their final comments. The cochairs thenrevised the document and forwarded it to the entireCoordinating Committee for review and comment.A working group member presented the report tothe entire NHBPEP Coordinating Committee attheir February 2002 meeting, and they providedoral and written comments to be included in thedocument. Two meetings of NHLBI staff and thecochairs were held to address and incorporate theCoordinating Committee comments. Thereafter,the penultimate draft of the report was preparedand sent to the Coordinating Committee, whounanimously voted to approve it.The development of this report was funded entirelyby the NHLBI. The members of the working group,NHBPEP Coordinating Committee, and reviewersserved as volunteers without remuneration.2EVIDENCE OF CLASSIFICATIONSThe studies that provided evidence supporting therecommendations of this report were classified andreviewed by the staff, cochairs, and working groupmembers. The scheme used for classification of theevidence is adapted from Last and Abramson.8MMeta-analysis; use of statistical methodsto combine the results from clinical trialsRaRandomized controlled trials; also knownas experimental studiesReRetrospective analysis; also known ascase-control studiesFProspective study; also known as cohortstudies, including historical or prospectivefollowup studiesXCross-sectional survey; also known asprevalence studiesPrPrevious review or position statementsCClinical interventions (nonrandomized)These symbols are appended to the citations inthe text and reference list.

Lifetime Burden ofElevated Blood PressureAge-related increase in blood pressure is a typicaloccurrence in most but not all populations.Accordingly, the prevalence of hypertension increaseswith increasing age, such that more than one ofevery two adults older than 60 years of age hashypertension.6X Experience in the Framingham HeartStudy suggests that the residual lifetime risk forhypertension is 90 percent and the probability ofreceiving antihypertensive medication is 60 percentfor middle-aged and elderly individuals.9F Highblood pressure increases morbidity and mortalityfrom CHD, stroke, congestive heart failure, and endstage renal disease.1F,10F,11F There is no convincingevidence of a J-shaped relationship or a “threshold”below which the relationship between level of bloodpressure and risk of cardiovascular and renal diseasesis not observed.12Pr The association of systolic bloodpressure with risk of cardiovascular and renal diseasesis stronger than the corresponding relationshipfor diastolic blood pressure.13M In light of suchknowledge, this advisory isprimarily focused on systolicblood pressure.2women indicated that persons with a low CVD-riskprofile (serum cholesterol level 200 mg/dL [5.18mmol/L], blood pressure 120/80 mmHg, andno current cigarette smoking) have a 72 percentto 85 percent lower mortality from CVD and a40 percent to 58 percent lower mortality fromall causes compared with persons who have one ormore of three modifiable cardiovascular risk factors.14FThe estimated greater life expectancy for the low-riskgroup ranged from 5.8 to 9.5 years. Computer programs and risk-calculating charts are available to assistclinicians and public health workers in determiningrisk (http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov).15MHigh blood pressure is onlyone of several proven majormodifiable risk factors forcardiovascular disease (CVD).In combination, these factorsprovide a powerful basis forpredicting risk and preventingcardiovascular complications inthe general population. A recentreport of large cohort studiesconducted in 366,559 youngand middle-aged men and3

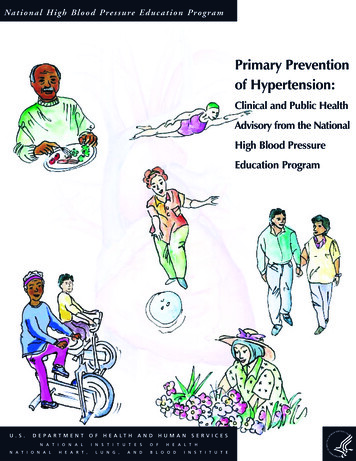

3Approaches to Primary Preventionof HypertensionHypertension can be prevented by complementaryapplication of strategies that target the generalpopulation and individuals and groups at higher riskfor high blood pressure. Lifestyle interventions aremore likely to be successful and the absolute reductions in risk of hypertension are likely to be greaterwhen targeted in persons who are older and thosewho have a higher risk of developing hypertensioncompared with their counterparts who are youngeror have a lower risk. However, prevention strategiesapplied early in life provide the greatest long-termpotential for avoiding the precursors that lead tohypertension and elevated blood pressure levels andfor reducing the overall burden of blood pressurerelated complications in the community.POPULATION-BASED STRATEGYA population-based approach aimed at achieving adownward shift in the distribution of blood pressurein the general population is an important componentfor any comprehensive plan to prevent hypertension.As shown in the Figure on the next page, a smalldecrement in the distribution of systolic bloodpressure is likely to result in a substantial reductionin the burden of blood pressure-related illness.16PrIn an analysis based onFramingham Heart Studyexperience, Cook et al.concluded that a 2 mmHgreduction in the populationaverage of diastolic bloodpressure for white U.S. residents 35 to 64 years of agewould result in a 17 percentdecrease in the prevalence ofhypertension, a 14 percentreduction in the risk of strokeand transient ischemic attacks,and a 6 percent reduction inthe risk of CHD.17F Publichealth approaches, such as loweringsodium content or caloric density in the food supply,and providing attractive, safe, and convenientopportunities for exercise are ideal population-basedapproaches for reduction of average blood pressurein the community. Enhancing access to appropriatefacilities (parks, walking trails, bike paths) andto effective behavior change models is a usefulstrategy for increasing physical activity in thegeneral population.18INTENSIVE TARGETED STRATEGYThe greatest long-termpotential for avoiding hypertension is to apply preventionstrategies early in life.4More intensive targeted approaches, aimed atachieving a greater reduction in blood pressure inthose who are most likely to develop hypertension,complement the previously mentioned populationbased strategies for prevention of hypertension.Groups at high risk for hypertension include thosewith a high-normal blood pressure, a family historyof hypertension, African American (black) ancestry,

overweight or obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, excessintake of dietary sodium and/or insufficient intakeof potassium, and/or excess consumption of alcohol.Contexts in which intensive targeted interventionscan be conducted to prevent hypertension inAfrican Americans and older Americans include notonly health care settings but also senior centers andfaith-based organizations that have blood pressurescreening and referral programs.Prevalence, %FIGURE:Reducing the average diastolicblood pressure in the U.S.population by 2 mmHgwould result in a 17 percentdecrease in the prevalenceof hypertension Systolic Blood Pressure DistributionsBefore interventionAfter interventionReduction in BPBlood pressure, mmHgReduction in BP(mmHg)% Reduction in er R. Hypertension. 1991;17(Suppl 1):I16–20.5

4Interventions With Documented EfficacyThe 1993 recommendations included weight loss,reduced intake of dietary sodium, moderation inalcohol consumption, and increased physical activityas the best proven interventions for prevention ofhypertension. Since then, further evidence insupport of these recommendations has emerged.In addition, potassium supplementation andmodification of eating patterns has been shown tobe beneficial in prevention of hypertension. Briefdescriptions of the six recommended lifestyles withproven efficacy for prevention of hypertension arepresented in the Box on page 9. A summary ofselected intervention efficacy experience publishedsince 1993 is presented in the following sections.WEIGHT LOSSA comprehensive review of the evidence supportingthe value of modest reductions in body weight isprovided in the Clinical Guidelines for the Identification,Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesityin Adults.19Pr He et al. reported on the experience of181 normotensive persons who had participated inPhase I of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention.20FDuring their initial 18 months of active interventionA sustained weight loss of9.7 lb (4.4kg) or more canreduce systolic and diastolicblood pressure by 5.0 and7.0 mmHg, respectively.6those assigned to the weight loss group reducedtheir body weight by 7.7 lb (3.5 kg) and theirsystolic and diastolic blood pressures by 5.8 and3.2 mmHg, respectively. After 7 years of followup,the incidence of hypertension was 18.9 percentin the weight loss group and 40.5 percent in thecontrol group. These findings suggest that weightloss interventions produce benefits that persist longafter the cessation of the active intervention. Inphase II of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention,the 595 participants assigned to a weight loss counseling intervention experienced a 21 percent reductionin incidence compared with 596 counterparts assignedto usual care.21Ra Weight loss participants who wereable to lose 9.7 lb (4.4 kg) or more and to sustain thisweight loss through the 36 month period of followupexperienced average reduction in systolic and diastolicblood pressure of 5.0 and 7.0 mmHg, respectively.22RaDIETARY SODIUM REDUCTIONAt least three meta-analysis of the efficacy ofreduced sodium intake in lowering blood pressurehave been published since 1993.23M,24M,25M In allthree reports, sodium reduction was associated witha small but significant reduction in systolic bloodpressure in normotensive persons. ln a meta-analysisof 12 randomized controlled trials conducted in1,689 normotensive participants, Cutler andcolleagues estimated that an average reduction of77 mmol/d in dietary intake of sodium resulted ina 1.9 mmHg (95 percent confidence interval [CI],1.2–2.6 mmHg) decrement in systolic blood pressureand a 1.1 mmHg (95 percent CI, 0.6 –1.6 mmHg)decline in diastolic blood pressure.23M

In a randomized controlled trial (Dietary Approachesto Stop Hypertension [DASH]-Sodium Trial) conducted in 412 persons with an average systolic bloodpressure of 120 to 159 mmHg and an average diastolic blood pressure of 80 to 95 mmHg, a reductionin sodium intake from a high level (mean urinarysodium excretion, 142 mmol/d) to an intermediatelevel (mean urinary sodium excretion, 107 mmol/d)reduced systolic blood pressure by 2.1 mmHg(P .001) during consumption of a usual Americancontrol diet and by 1.3 mmHg (P .03) during consumption of a DASH diet that was high in fruits andvegetables and lowfat dairy products.26Ra Reducingsodium intake from the intermediate level to a lowerlevel (mean urinary sodium excretion, 65 mmol/d)resulted in an additional reduction in systolic bloodpressure of 4.6 mmHg during consumption of thecontrol diet (P .001) and 1.7 mmHg reductionduring consumption of the DASH diet (P .01). Theeffects of sodium reduction were greater for thosewho ate the typical American diet, compared withthose on the DASH diet.26Ra These findings areconsistent with current national recommendationsfor a moderately low intake of dietary sodium (nomore than 100 mmol/d: approximately 6 g ofsodium chloride or 2.4 g of sodium per day) byall Americans5Pr and suggest that an even lowerlevel of dietary sodium intake may result in agreater reduction in blood pressure.In a large, long-term community-basedrandomized controlled trial,Whelton et al. reported that amoderate reduction of dietarysodium intake resulted in anadditional 4.3 mmHg reduction in systolic bloodpressure among olderpersons with hypertension whose bloodpressures werealready well controlled by a singleantihypertensiveThe upper limit of dietarysodium intake is 2,400 mgper day.Lower intake of dietarysodium reduces the riskof cardiovascular disease,especially in those whoare also overweight.medication.27Ra For those assigned to a combinedsodium reduction and weight loss intervention, thecorresponding additional reduction in systolic bloodpressure was 5.5 mmHg. The need for antihypertensive medication during a subsequent 18 monthperiod of followup was reduced by 31 percent and53 percent in those assigned to sodium reductionand combined sodium reduction and weight loss,respectively. Although not directly relevant to prevention of hypertension, the results of this trial provideadditional evidence in support of the role of weightloss and moderate sodium reduction as means toreduce blood pressure, even for persons who havebeen taking antihypertensive medication.In the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study,He et al. reported that a 100 mmol higher level ofsodium intake in overweight persons was associatedwith a 32 percent increase in stroke incidence, a89 percent increase in stroke mortality, a 44 percentincrease in CHD mortality, a 61 percent increasein CVD mortality, and a 39 percent increase inmortality from all causes.28F In Finland in a prospective population-based cohort study conducted in1,173 men and 1,263 women 25 to 64 years ofage, the hazard ratios for CHD, CVD, and all-causemortality, associated with a 100 mmol higher level of7

24 h urinary sodium excretion, were 1.51 (95 percentCI, 1.14–2.00), 1.45 (95 percent CI, 1.14–1.84),and 1.26 (95 percent CI, 1.06 –1.50), respectively.29FThere was a significant interaction between sodiumexcretion and body mass index for cardiovascular andtotal mortality, with sodium being a stronger predictorof mortality in men who were overweight. These datasupport the premise that a lower intake of dietarysodium reduces the risk of subsequent CVD, especiallyin those who are also overweight.INCREASED PHYSICAL ACTIVITYA meta-analysis by Whelton et al. in which theexperience of 1,108 normotensive persons enrolledin 27 randomized controlled trials was included,identified a 4.04 mmHg (95 percent CI, 2.75–5.32)reduction in systolic blood pressure in those assignedto aerobic exercise compared with the controlgroup.30M The magnitude of the intervention effectappears to be independent of the intensity of theexercise program. In the Physical Activity and Health:A Report of the Surgeon General it is recommended thatpersons exercise for at least 30 minutes on most, ifnot all, days of the week.31PrMODERATION OF ALCOHOL CONSUMPTIONIn a meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials,Xin et al. reported that decreased consumption ofalcohol (the median reduction in self-reported consumption of alcohol was 76 percent, with a rangefrom 16 percent to 100 percent) was associatedwith a reduction in blood pressure, and that therelationship between reduction in mean percentageof alcohol and decline in blood pressure wasdose-dependent.32M Pooling of the experienceIt is recommended that personsexercise for at least 30 minuteson most, if not all, days ofthe week.8Potassium supplementationlowers blood pressure inboth hypertensive andnormotensive persons.of 269 normotensive participants enrolled in6 randomized controlled trials identified a reducedconsumption of alcohol as being associated witha 3.56 mmHg (95 percent CI, 2.51– 4.61) lowerlevel of systolic blood pressure and a 1.80 mmHg(95 percent CI, 0.58–3.03) lower level of diastolicblood pressure.32M Therefore, it is recommendedthat alcohol consumption be limited to no morethan 1 oz (30 mL) ethanol (e.g., 24 oz [720 mL]beer, 10 oz [300 mL] wine, or 2 oz [60 mL]100-proof whiskey) per day in most men and tono more than 0.5 oz (15 mL) ethanol per day inwomen and lighter weight persons.POTASSIUM SUPPLEMENTATIONClinical trials and meta-analysis indicate thatpotassium supplementation lowers blood pressurein both hypertensive and normotensive persons.In a meta-analysis of the results from 12 trialswith 1,049 normotensive participants, Wheltonet al. reported that potassium supplementation(median, 75 mmol/d) lowered systolic blood pressure by 1.8 mmHg (95 percent CI, 0.6–2.9) anddiastolic blood pressure by 1.0 mmHg (95 percentCI, 0.0–2.1).33M The effects of potassium supplementation appeared greater in those with higherlevels of sodium intake.MODIFICATION OF WHOLE DIETSThe DASH and DASH-Sodium trials used dietaryinterventions that incorporated several nutritionalrecommendations for lowering blood pressure.26Ra,34RaIn the 8 week DASH trial, study participants with asystolic blood pressure less than 160 mmHg and adiastolic blood pressure between 80 and 95 mmHg

were randomly assigned to one of the following dietgroups: (1) a control diet that was low in fruits, vegetables, and dairy products, with a fat content typicalof the average diet in the United States, (2) a similardiet that was rich in fruits and vegetables, or (3) aDASH diet that was rich in fruits, vegetables andlow-fat dairy products but reduced in saturated andtotal fat.35 Among the 326 normotensive DASHparticipants (blood pressure 140/90 mmHg),the DASH diet reduced systolic blood pressure by3.5 mmHg (P .001).34Ra In a subsequent DASHSodium study, normotensive persons assigned tothe DASH diet and a low level of urinary sodiumexcretion (67 mmol/d) reduced their systolic bloodpressure by 7.1 mmHg (7.2 mmHg for blacks and6.9 mmHg for others) compared with counterpartswho were assigned to the control diet and a highlevel of urinary sodium excretion (141 mmol/d).26RaA significant reduction in diastolic blood pressurewas also observed. Furthermore, the beneficial effectsof the DASH diet and the DASH diet with reducedsodium occurred broadly in all major subgroups ofthe population.36RaThe beneficial effects of thelow sodium DASH dietoccurred in all major subgroups of the population.Lifestyle Modifications for Primary Prevention of Hypertension1.Engage in regular aerobic physical activity such as brisk walking (at least 30 minutesper day, most days of the week).2.Maintain normal body weight for adults (body mass index 18.5 – 24.9 kg/m2).3.Limit alcohol consumption to no more than 1 oz (30 mL) ethanol (e.g., 24 oz [720 mL]of beer, 10 oz [300 mL] of wine, or 2 oz [60 mL] 100-proof whiskey) per day in mostmen and to no more than 0.5 oz (15 mL) of ethanol per day in women and lighterweight persons.4.Reduce dietary sodium intake to no more than 100 mmol per day (approximately2.4 g of sodium or 6 g of sodium chloride).5.Maintain adequate intake of dietary potassium (more than 90 mmol [3,500 mg] per day).6.Consume a diet that is rich in fruits and vegetables and in lowfat dairy products witha reduced content of saturated and total fat (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension[DASH] eating plan).9

5Interventions With Uncertainor Less Proven EfficacyCALCIUM SUPPLEMENTATIONConsistent with previous observations, a recent metaanalysis of randomized controlled clinical trials suggeststhat calcium supplementation results in only a smallreduction in blood pressure.37M This effect has onlybeen observed in those with hypertension. However,for general health, it is prudent to recommendadequate calcium

Education Program Working Group Report on Primary Prevention of Hypertension7Pr and to address the public health challenges of hypertension described in the JNC VIreport.5Pr METHOD OF GUIDELINE DEVELOPMENT The National High Blood Pressure Education Program (NHBPEP) Coordinating Committee consists of representatives from 38 national