Transcription

Weight Gain During Pregnancy:Reexamining the GuidelinesKathleen M. Rasmussen and Ann L. Yaktine, EditorsCommittee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight GuidelinesFood and Nutrition Board and Board on Children, Youth, and FamiliesPREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS500 Fifth Street, N.W.Washington, DC 20001NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of theNational Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy ofSciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of thecommittee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard forappropriate balance.This study was supported by Contract No. HHSH250200446009I TO HHSH240G5806 between theNational Academy of Sciences and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources andServices Administration; Contract No. 200-2007-M-21619 between the National Academy of Sciencesand Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity and Obesity;Contract No. N01-OD-4-2139 TO 192 between the National Academy of Sciences and National Institutesof Health Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Contract No. N01-OD-4-2139 TO 192between the National Academy of Sciences and National Institutes of Health National Institute ofDiabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Contract No. HHSP23300700522P between the NationalAcademy of Sciences and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women’s Health;Contract No. HHSP23320070071P between the National Academy of Sciences and U.S. Department ofHealth and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; and Contract No. 21FY07-576 between the National Academy of Sciences and March of Dimes. Additional support camefrom U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health and the NationalMinority AIDS Council. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in thispublication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the organizations oragencies that provided support for this project.International Standard Book Number 0-309-XXXXX-X (Book)International Standard Book Number 0-309- XXXXX -X (PDF)Library of Congress Control Number: 00 XXXXXXAdditional copies of this report are available from the National Academies Press, 500 Fifth Street, N.W.,Lockbox 285, Washington, DC 20055; (800) 624-6242 or (202) 334-3313 (in the Washingtonmetropolitan area); Internet, http://www.nap.edu.For more information about the Institute of Medicine, visit the IOM home page at: www.iom.edu.Copyright 2009 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.Printed in the United States of America.The serpent has been a symbol of long life, healing, and knowledge among almost all cultures andreligions since the beginning of recorded history. The serpent adopted as a logotype by the Institute ofMedicine is a relief carving from ancient Greece, now held by the Staatliche Museen in Berlin.Suggested citation: IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2009. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining theGuidelines. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS

PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS

The National Academy of Sciences is a private, nonprofit, self-perpetuating society of distinguished scholars engaged inscientific and engineering research, dedicated to the furtherance of science and technology and to their use for the generalwelfare. Upon the authority of the charter granted to it by the Congress in 1863, the Academy has a mandate that requires it toadvise the federal government on scientific and technical matters. Dr. Ralph J. Cicerone is president of the National Academy ofSciences.The National Academy of Engineering was established in 1964, under the charter of the National Academy of Sciences, as aparallel organization of outstanding engineers. It is autonomous in its administration and in the selection of its members, sharingwith the National Academy of Sciences the responsibility for advising the federal government. The National Academy ofEngineering also sponsors engineering programs aimed at meeting national needs, encourages education and research, andrecognizes the superior achievements of engineers. Dr. Charles M. Vest is president of the National Academy of Engineering.The Institute of Medicine was established in 1970 by the National Academy of Sciences to secure the services of eminentmembers of appropriate professions in the examination of policy matters pertaining to the health of the public. The Institute actsunder the responsibility given to the National Academy of Sciences by its congressional charter to be an adviser to the federalgovernment and, upon its own initiative, to identify issues of medical care, research, and education. Dr. Harvey V. Fineberg ispresident of the Institute of Medicine.The National Research Council was organized by the National Academy of Sciences in 1916 to associate the broad communityof science and technology with the Academy’s purposes of furthering knowledge and advising the federal government.Functioning in accordance with general policies determined by the Academy, the Council has become the principal operatingagency of both the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Engineering in providing services to thegovernment, the public, and the scientific and engineering communities. The Council is administered jointly by both Academiesand the Institute of Medicine. Dr. Ralph J. Cicerone and Dr. Charles M. Vest are chair and vice chair, respectively, of theNational Research Council.www.national-academies.orgPREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS

COMMITTEE ON THE REEXAMINATION OF IOM PREGNANCY WEIGHTGUIDELINESKATHLEEN M. RASMUSSEN (Chair), Professor of Nutrition, Division of NutritionalSciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NYBARBARA ABRAMS, Professor, School of Public Health, University of California–BerkeleyLISA M. BODNAR, Assistant Professor, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh,PACLAUDE BOUCHARD, Executive Director and George A. Bray Chair in Nutrition, PenningtonBiomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LANANCY BUTTE, Professor of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TXPATRICK M. CATALANO, Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Case WesternReserve University, Cleveland, OHMATTHEW GILLMAN, Professor, Department of Ambulatory Care and Prevention, HarvardMedical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Boston, MAFERNANDO A. GUERRA, Director of Health, San Antonio Metropolitan Health District, TXPAULA A. JOHNSON, Executive Director, Connors Center for Women’s Health and GenderBiology, Chief, Division of Women’s Health, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MAMICHAEL C. LU, Associate Professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Public Health, Schools ofMedicine and Public Health, University of California–Los AngelesELIZABETH R. McANARNEY, Professor and Chair Emerita, Department of Pediatrics, Schoolof Medicine and Dentistry, University of Rochester, NYRAFAEL PEREZ-ESCAMILLA, Professor of Nutritional Sciences & Public Health, Director,NIH EXPORT Center for Eliminating Health Disparities among Latinos, University ofConnecticut, StorrsDAVID A. SAVITZ, Charles W. Bluhdorn Professor of Community & Preventive Medicine,Director, Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Disease Prevention Institute, Mount Sinai School ofMedicine, New York, NYANNA MARIA SIEGA-RIZ, Associate Professor, Department of Epidemiology, School ofPublic Health, University of North Carolina–Chapel HillStudy StaffANN L. YAKTINE, Senior Program OfficerHEATHER B. DEL VALLE, Research AssociateM. JENNIFER DATILES, Senior Program AssistantANTON BANDY, Financial OfficerGERALDINE KENNEDO, Administrative AssistantLINDA D. MEYERS, Food and Nutrition Board DirectorROSEMARY CHALK, Director, Board on Children, Youth, and FamiliesPREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFSv

PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFSvi

ReviewersThis report has been reviewed in draft form by individuals chosen for their diverseperspectives and technical expertise, in accordance with procedures approved by the NationalResearch Council's (NRC’s) Report Review Committee. The purpose of this independent reviewis to provide candid and critical comments that will assist the institution in making its publishedreport as sound as possible and to ensure that the report meets institutional standards forobjectivity, evidence, and responsiveness to the study charge. The review comments and draftmanuscript remain confidential to protect the integrity of the deliberative process. We wish tothank the following individuals for their review of this report:Haywood Brown, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Duke University Medical Center,Durham, NCCutberto Garza, Boston College, MASusan Gennaro, William F. Connell School of Nursing, Boston College, MAWilliam Goodnight, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Maternal-FetalMedicine, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill School of MedicineErica P. Gunderson, Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente, Oakland, CAMaxine Hayes, Department of Health, State of Washington, TumwaterLorraine V. Klerman, The Heller School for Social Policy and Management, BrandeisUniversity, Waltham, MAKristine G. Koski, School of Dietetics and Human Nutrition, McGill University, Ste. Anne deBellevue, Quebec, CanadaCharles Lockwood, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences,Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CTDawn Misra, Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Department of Family Medicine andPublic Health Sciences, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MIJose M. Ordovas, Nutrition and Genomics Laboratory, Jean Mayer USDA Human NutritionResearch Center on Aging, Tufts University, Boston, MARoy M. Pitkin, University of California–Los Angeles (Professor Emeritus)David Rush, Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy (Professor Emeritus), TuftsUniversity, Boston, MAJeanette South-Paul, Department of Family Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, PAAlthough the reviewers listed above have provided many constructive comments andsuggestions, they were not asked to endorse the conclusions or recommendations nor did theysee the final draft of the report before its release. The review of this report was overseen by NealA. Vanselow, Tulane University, Professor Emeritus and Nancy E. Adler, Departments ofPsychiatry and Pediatrics and Center for Health and Community, University of California–SanFrancisco.PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFSvii

Appointed by the NRC and Institute of Medicine, they were responsible for making certainthat an independent examination of this report was carried out in accordance with institutionalprocedures and that all review comments were carefully considered. Responsibility for the finalcontent of this report rests entirely with the authoring committee and the institution.PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFSviii

PrefaceIn the last century, many answers have been given by health professionals to the question“how much weight should I gain while I am pregnant?” In the early 1900's, the answer was oftenonly 15-20 pounds. Between 1970 and 1990, the guideline for weight gain during pregnancy washigher, 20-25 pounds, and in 1990, with the publication of Nutrition During Pregnancy, it wenthigher still for some groups of women. This most recent guideline reflected new knowledgeabout the importance of maternal body fatness before conception, as measured by body massindex, for the outcome of pregnancy. It had become clear that heavier women could gain lessweight and still deliver an infant of good size. Since that time, the obesity epidemic has notspared women of reproductive age. In our population today, more women of reproductive age areseverely obese (obesity class III; 8 percent) than are underweight (3 percent) and their short- andlong-term health has become a concern in addition to the size of the infant at birth. Clearly thetime had come to reexamine the guidelines for weight gain during pregnancy.To prepare for this possibility, the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicineheld a workshop in 2006 to evaluate the availability of data that could be used reexamine thecurrent guidelines. Based on the outcome of this workshop, numerous federal agencies(Department of Health and Human Services: Health Resources Services Administration; Centersfor Disease Control and Prevention Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity;National Institutes of Health: The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health andDevelopment; National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Division ofNutrition Research Coordination Office on Women’s Health; Office on Disease Prevention andHealth Promotion; and Office on Minority Health; as well as the March of Dimes) agreed tosponsor the work of this committee.The committee was asked to review the determinants and a wide range of short- and longterm consequences of variation in weight gain during pregnancy for both the mother and herinfant. Based on the outcome of this review, the committee was asked to recommend revisions tothe current guidelines if this was deemed to be necessary. In addition, the committee was askedto consider the approaches that might be necessary to promote appropriate weight gain and toidentify gaps in knowledge and make recommendations about priorities for future research.Although many studies relevant to the committee’s charge have been published since 1990and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) completed their report Outcomesof Maternal Weight Gain while the committee was gathering data, many gaps in knowledgeremained. To address this problem, the committee held a public session with project sponsors,and two workshops. We are grateful to those who participated in these sessions for sharing theirexperience and wisdom. We are also grateful to a number of individuals who supplied data to thecommittee: Aimin Chen, Amy Branum, Alan Ryan, Andrea Sharma, Joyce Martin, SharonKirmeyer, K.S. Joseph, Marie Cedergren, Raul Artal, and with special thanks to Patricia Dietz.The committee also commissioned additional analyses of data from both Denmark and theUnited States. We thank our consultants, Ellen Aagaard Nohr, Amy Herring, and Cheryl SteinPREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFSix

for these analyses and for their contributions to the committee’s work. The committee also feltthat it was important to understand what would be involved in analyzing the trade-off betweenmother and infant in risk of adverse outcomes of variation in weight gain during pregnancy. Toaccomplish this, we commissioned such an analysis based on the data at hand. We thank ourconsultant, James Hammitt, for conducting these analyses and for his contribution to thecommittee’s work.The committee’s 14 members gave freely of their expertise and volunteered their time andenergy in all aspects of the preparation of this report, from developing its intellectual framework,writing the text and deliberating about the recommendations and conclusions of the report. Theirefforts merit our sincere gratitude.The committee received excellent staff support from Ann Yaktine, Study Director, HeatherDel Valle, Research Associate and Jennifer Datiles, Senior Program Assistant. Their effort onour behalf is sincerely appreciated. Both the Director of the Food and Nutrition Board, LindaMeyers, and the Director of the Board on Children, Youth and Families, Rosemary Chalk,contributed their wisdom and support to this effort and we thank them for it.Kathleen M. Rasmussen, ChairCommittee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight GuidelinesPREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFSx

ContentsSUMMARY12345678910Setting the Stage for Revising Pregnancy Weight Guidelines:Conceptual FrameworkDescriptive Epidemiology and TrendsComposition and Components of Gestational Weight Gain:Physiology and MetabolismDeterminants of Gestational Weight GainConsequences of Gestational Weight Gain for the MotherConsequences of Gestational Weight Gain for the ChildDetermining Optimal Weight GainApproaches to Achieving Recommended Gestational Weight GainOpen Session and Workshop AgendasCommittee Member Biographical SketchesAPPENDIXES*A Glossary and Supplemental InformationB Supplementary Information on Nutritional IntakeC Supplementary Information on Composition andComponents of Gestational Weight GainD Summary of Determinants of Gestational Weight GainE Results from the Evidence-based Report on Outcomes of Maternal Weight GainF Data TablesG Consultant E-1F-1G-1Index (to be included in final publication)*Appendixes A through G are not printed in this book, but can be found on the CD at theback of the report or online at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record id 12584.PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFSxi

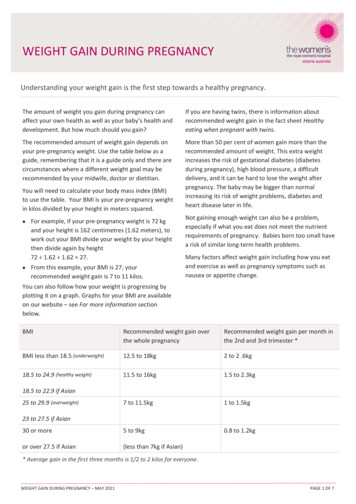

SummarySince 1990, the last time the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released guidelines for weight gainduring pregnancy, many key aspects of the health of women of childbearing age have changed.This population now includes a higher proportion of women from racial/ethnic subgroups andprepregnancy body mass index (BMI) and gestational weight gain (GWG) have increased amongall population subgroups. Moreover, high rates of overweight and obesity are common in thepopulation subgroups that are at risk for poor maternal and child health outcomes. Finally,women are also becoming pregnant at an older age and, as a result, are entering pregnancy morecommonly with chronic conditions such as hypertension or diabetes, which put them at risk forpregnancy complications and may lead to increased morbidity during their post-pregnancy years.These and other factors suggested a need to reexamine the IOM (1990) guidelines for weightgain during pregnancy and consider whether revision might be warranted.In response to these concerns, sponsors1 asked the Food and Nutrition Board of the IOM andthe Board on Children, Youth, and Families in the Division of Behavioral and Social Sciencesand Education of the National Research Council to review the IOM (1990) recommendations forweight gain during pregnancy. Specifically, the committee was asked to review evidence onrelationships between weight gain patterns before, during, and after pregnancy, and maternal andchild health outcomes; consider factors within a life-stage framework associated with outcomessuch as lactation performance, postpartum weight retention, cardiovascular and other chronicdiseases; and recommend revisions to existing guidelines where necessary. Finally, thecommittee was asked to recommend ways to encourage the adoption of the weight gainguidelines through consumer education, strategies to assist practitioners, and public healthstrategies.GUIDELINES FOR WEIGHT GAIN DURING PREGNANCYThe new guidelines for GWG that are shown in Table S-1 are formulated as a range for eachcategory of prepregnancy BMI. This approach reflects the imprecision of the estimates on whichthe recommendations are based, the reality that good outcomes are achieved within a range ofweight gains, and the many additional factors that may need to be considered for an individualwoman. It is important to note that these guidelines are intended for use among women in theUnited States. They may be applicable to women in other developed countries. However, theyare not intended for use in areas of the world where women are substantially shorter or thinnerthan American women or where adequate obstetric services are unavailable.The new guidelines differ from those issued in 1990 in two ways. First, they are based on theWorld Health Organization (WHO) cutoff points for the BMI categories instead of the previousones, which were based on categories derived from the Metropolitan Life Insurance tables.1Sponsors include: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration,; Centers for DiseaseControl and Prevention, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity; National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Healthand Human Development, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; U.S. Department of Health and Human ServicesOffice on Women’s Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office on Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; and the Marchof Dimes. Additional support came from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health and the National MinorityAIDS Council.PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS1

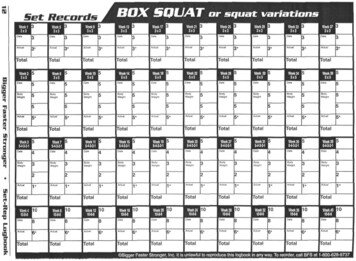

S-2WEIGHT GAIN DURING PREGNANCYSecond, and more importantly, the new guidelines include a specific, relatively narrow range ofrecommended gain for obese women.TABLE S-1 New Recommendations for Total and Rate of Weight Gain during Pregnancy, byPrepregnancy BMITotal Weight GainPrepregnancy BMIUnderweight( 18.5 kg/m2)Normal weight(18.5–24.9 kg/m2)Overweight(25.0–29.9 kg/m2)Obese( 30.0 kg/m2)Range in kg12.5–18Range in �20Rates of Weight Gain*2nd and 3rd TrimesterMean (range) inMean (range) 7)0.220.5(0.17–0.27)(0.4–0.6)* Calculations assume a 0.5–2 kg (1.1– 4.4 lbs) weight gain in the first trimester (based on Siega-Riz et al.,1994; Abrams et al., 1995; Carmichael et al., 1997)These new guidelines should be considered in the context of data on women’s reportedGWG. Data from several large groups of women indicate that the mean gains of underweightwomen fall within the new guidelines, but some normal weight women may exceed these newguidelines and a majority of overweight or obese women will likely exceed them. These dataprovide a strong reason to assume that interventions will be needed to assist women, particularlythose who are overweight or obese at the time of conception, in meeting the guidelines. Theseinterventions may need to occur at both the individual and community levels and may need toinclude components related to both improved dietary intake and increased physical activity.The committee intends that the guidelines shown in Table S-1 be used in concert with goodclinical judgment as well as a discussion between the woman and her care provider about dietand exercise. If a woman’s GWG is not within the proposed guidelines, clinicians shouldconsider other relevant clinical evidence, modifiable factors that might be causing excessive orinadequate gain, and information on the nature of excess GWG (e.g. fat or edema) as well asboth the adequacy and consistency of fetal growth before suggesting that a woman modify herpattern of weight gain.Special PopulationsWomen of Short StatureThe IOM (1990) report recommended that women of short stature ( 157 cm) gain at thelower end of the range for their prepregnant BMI. The committee was unable to identifyevidence sufficient to continue to support a modification of GWG guidelines for women of shortstature. Although women of short stature had an increased risk of emergency cesarean delivery,this risk was not modified by GWG. Women of short stature did not have an increased risk ofhaving an small-for-gestational age (SGA) or large-for-gestational age (LGA) infant or ofexcessive postpartum weight retention over taller women.PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS

SUMMARYS-3Pregnant AdolescentsEvidence available since the IOM (1990) report is also insufficient to continue to support amodification of the GWG guidelines for adolescents ( 20 years old) during pregnancy. Thecommittee also determined that prepregnancy BMI could be adequately categorized inadolescents by using the WHO cutoff points for adults, in part because of the impracticality ofusing pediatric growth charts in obstetric practices. Adolescents who follow adult BMI cutoffpoints will likely be categorized in a lighter group and thus advised to gain more; however,younger adolescents often need to gain more to improve birth outcomes.Racial or Ethnic GroupsAlthough an increasing proportion of pregnant U.S. women are members of racial or ethnicminority groups, the limited data available to the committee from commissioned analysessuggested that membership in one of these groups did not modify the association between GWGand the outcome of pregnancy. As a result, the committee concluded that its recommendationsshould be generally applicable to the various racial or ethnic subgroups that make up theAmerican population although additional research is needed to confirm this approach.Women with Multiple FetusesRecent data suggest that the weight gain of women with twins who have good outcomesvaries with prepregnancy BMI as is clearly the case for women with singleton fetuses. Inasmuchas the committee was unable to conduct the same kind of analysis for women with twins as it didfor women with singletons, the committee offers the following provisional guidelines: normalweight women should gain 17-25 kg (37-54 pounds), overweight women, 14-23 kg (31-50pounds) and obese women, 11-19 kg (25-42 pounds) at term. Insufficient information wasavailable with which to develop even a provisional guideline for underweight women withmultiple fetuses. These provisional guidelines reflect the interquartile (25th to 75th percentiles)range of cumulative weight gain among women who delivered their twins, who weighed 2,500g on average, at 37-42 weeks of gestation.DEVEOPMENT OF THE GUIDELINES FOR WEIGHT GAIN DURINGPREGNANCYThe committee worked from the perspectives that the reproductive cycle begins beforeconception and continues through the first year postpartum and that maternal weight statusthroughout the entire cycle affects both the mother and her child. To inform its review of theliterature and to guide the organization of its report, the committee reevaluated the conceptualframework that guided the development of the IOM (1990) report. To account for advances inour scientific understanding of the determinants and consequences of GWG, the committeedeveloped a modified conceptual framework (Figure S-1). However, it retained the samescientific approach and epidemiologic conventions used previously and discussed in detail in theIOM (1990) report.PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS

S-4WEIGHT GAIN DURING PREGNANCYFIGURE S-1 Schematic summary of potential determinants and consequences for gestational weightgain.SOURCE: Modified from IOM, 1990.PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS

SUMMARYS-5The committee began its work by considering appropriate BMI cutoff points and describingtrends over time in maternal prepregnancy BMI and GWG among American women. In addition,data were sought on both the determinants and consequences of GWG. The search for such datarevealed major gaps in data collection and analysis.Key Finding S-1: The WHO cutoff points for categorizing BMI have been widely adoptedand should be used for categorizing prepregnancy BMI as well.Key Finding S-2: Currently available data sources are inadequate for studying nationaltrends in GWG, or postpartum weight, or their determinants.Action Recommendation S-1: The committee recommends that the Department of Healthand Human Services conduct routine surveillance of GWG and postpartum weight retention on anationally representative sample of women and report the results by prepregnancy BMI(including all classes of obesity), age, racial/ethnic group, and socioeconomic status.Action Recommendation S-2: The committee recommends that all states adopt the revisedversion of the birth certificate, which includes fields for maternal prepregnancy weight, height,weight at delivery, and gestational age at the last measured weight. In addition, all states shouldstrive for 100 percent completion of these fields on birth certificates and collaborate to sharedata, thereby allowing a complete national picture as well as regional snapshots.Research Recommendation S-1: The committee recommends that the National Institutes ofHealth and other relevant agencies should provide support to researchers to conduct studies inlarge and diverse populations of women to understand how dietary intake, physical activity,dieting practices, food insecurity and, more broadly, the social, cultural and environmentalcontext affect GWG.In developing its recommendations, the committee identified a set of consequences for theshort- or long-term health of the mother and the child that are potentially causally related toGWG. These consequences included those evaluated in a systematic review of outcomes ofmaternal weight gain prepared for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) aswell as others based on data from the literature outside the time window considered in thatreport. To address conflicts and gaps within the available literature, the committee commissionedfour additional analyses from existing databases. The committee considered the results fromthese commissioned analyses in conjunction with evidence from published scientific literature.Postpartum weight retention, cesarean delivery, gestational diabetes mellitus, and pregnancyinduced hypertension or preeclampsia emerged from this process as being the most importantmaternal health outcomes. The committee removed preeclampsia and gestational diabetesmellitus from consideration because of the lack of sufficient evidence that GWG was a cause ofthese conditions. Postpartum weight retention and, in particular, unscheduled primary cesareandelivery were retained for further consideration.Measures of size at birth (e.g. SGA and LGA), preterm birth, and childhood obesity emergedfrom this process as being the most important infant health outcomes. The committee recognizedthat both SGA and LGA, when defined as 10

Between 1970 and 1990, the guideline for weight gain during pregnancy was higher, 20-25 pounds, and in 1990, with the publication of Nutrition During Pregnancy , it went higher still for some .