Transcription

Organizational Market Information Processes: Cultural Antecedents and New ProductOutcomesAuthor(s): Christine MoormanSource: Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 32, No. 3 (Aug., 1995), pp. 318-335Published by: American Marketing AssociationStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3151984 .Accessed: 23/09/2013 16:33Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at ms.jsp.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.American Marketing Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access toJournal of Marketing Research.http://www.jstor.orgThis content downloaded from 152.3.153.148 on Mon, 23 Sep 2013 16:33:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTINEMOORMAN*Organizationalresearch suggests that the way informationis used islikely to be a function of the presence of organizationalsystems orprocesses, in addition to individual manager activities. The authorsuggests that firmsvary theiremphasis on certain organizationalmarketinformationprocesses, such as informationacquisition, informationtransmission, conceptual use of information,and instrumentaluse ofinformation.The authorargues that the emphasis is determined,in part,by the congruence, or fit, among an organization'sculturalnorms andvalues and theorizes that the presence of these organizationalinformationprocesses affects new product outcomes. Survey resultsindicatethatclans dominatethe otherculturesin , suggesting that informationprocesses arefundamentally"people processes" that involve commitment and trustamong organizationalmembers.The results have importantimplicationsfor balancing internaland external orientationswithinfirms.The resultsalso indicate that the informationutilizationprocesses, especially thosethat are conceptual in nature, are strong predictors of new productperformance, timeliness, and creativity, indicating that competitiveadvantage is tied to informationutilizationactivitiesin lInformationAntecedents andNewOutcomesIinformationprocesses as they occur at the organizationallevel.1Organizationalresearch has a long traditionof researchsuggesting that the way informationis used is likely to be afunction of the presence of organizational systems or processes, in addition to individual manager activities (Cyertand March 1992; Daft and Weick 1984; Weick 1979). Thistraditionarguesthat an organization'sability to process andlearnfrom informationextends beyond the capacity of individual organizational members (Hedberg 1981). Instead,this ability evolves over time and is expressed in an organization's informationprocesses (Huber 1991), which may in-Marketing has historically addressed information processing and utilizationfrom the perspectiveof the individual decision maker (Deshpand6 and Zaltman 1982; Wiltonand Myers 1986), often examiningthe effect of informationon decision makers' performance (Glazer, Steckel, andWiner 1992; GlazerandWeiss 1993; Mahajan1992; Perkinsand Rao 1990). Marketingliteraturehas also focused on theeffects of organizationalcharacteristics,such as structureand communicationpatternson individualmanagers'use ofinformation(Deshpandeand Zaltman 1982; Hutt, Reingen,and Ronchetto 1988; Menon and Varadarajan1992; Mohrand Nevin 1990; Moorman,Deshpande,and Zaltman1993).Although such researchhas provided insight into information utilization and the various factors that influence it, themarketingliteraturehas yet to fully examine the natureof1Thereare a few recent exceptions in the marketingliterature.Kohli andJaworski(1990) have conceptualizedmarketorientationas involving a series of organizationalinformationprocesses (see also Day 1991; Narverand Slater 1990; Sinkula 1994). It is unclear whether the work of Deshpand6 and Zaltman(1982) is operatingat the individualor organizationallevel. However,the positioningof theirarticlesas involving the "use of specific marketresearchinformationby marketingmanagers"(Deshpand6andZaltman 1982, abstract),and their subsequentfocus on comparingthe useof informationby researchersto that of managers(Deshpand6and Zaltman1984) suggests they are operatingat the individuallevel. Despite this, theirinformationuse scale could be used at either the individual or organizational level.*Christine Moorman is Assistant Professor of Marketing, GraduateSchool of Business, Universityof Wisconsin, Madison. The authorthanksGeorge Day, Jan Heide, Anne Miner,J. Paul Peter,Aric Rindfleisch, CraigThompson,UCLA, Wharton,and Queen's UniversitySeminarParticipants,and threeanonymousreviewersfor their constructivecomments on an earlier version of this article.The authoralso appreciatesthe supportof editorsBartWeitz and Vijay Mahajan.Journal of MarketingResearchVol. XXXII(August 1995), 318-335318This content downloaded from 152.3.153.148 on Mon, 23 Sep 2013 16:33:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MarketInformationProcessesOrganizationalclude processes for acquiring,disseminating, and utilizinginformation(Beyer and Trice 1982). Such processes havebeen viewed as "knowledgeassets" (Winter 1987) that canbe leveraged to achieve competitive advantage(Cohen andLevinthal 1990; Leonard-Barton1991; Levitt and March1988).Despite potentialcontributionsto the marketingliterature,the organizationalview of informationprocesses is presently underutilized.My researchattemptsto addressthis deficiency by specifically resolving severalissues thatwould increase the contributionof the organizationalview to marketing. First, because no study has examined whetherindividual informationprocesses are empirically distinct fromorganizationalinformationprocesses, it is unclear whetherthese processes have been measured at the organizationallevel. Second, unlike previousresearch,which has tendedtofocus on a subset of organizationalinformationprocesses, Iattemptto explicate a more complete conceptualdomainforthese processes. Third, though researchhas focused on thestructural antecedentsof informationuse (Deshpand6andZaltman 1982; Kohli and Jaworski1990), previousresearchhas failed to understandthe cultural antecedentsof organizational informationprocessing in firms. Fourth, previousresearch has not provided empirical results regardinghoworganizationalinformationprocesses affect marketingperformance. The one exception, Jaworskiand Kohli's (1993)study,examines severalconsequencesof a firm'smarketorientation. However,they do not consider how the individualinformationprocesses within a firm's marketorientationcanhave different performanceoutcomes. Moreover,Jaworskiand Kohli's (1993) study and other conceptual work havebeen confined to assessing overall business performance,without regard to specific effects on new product performance, which previous research suggests is likely to bestrongly influenced by the natureof firm-level informationactivities, including information acquisition (Day 1991,1994; Dickson 1992), informationtransmission(Hutt,Reingen, and Ronchetto 1988; Imai, Nonaka, and Takeuchi1985), and information utilization (Clark and Fujimoto1991; Day 1994).I addressthese gaps in the literaturewith threekey objectives: (1) to conceive of a more complete set of organizational information processes and empirically distinguishthem from individual informationprocessing activities; (2)to examine culturalfactors as antecedentsof organizationalinformationprocesses; and (3) to investigate the effects ofthese organizationalinformationprocesses on several PROCESSESGlazer (1991, p. 2) defined marketinformationas "datathat have been organizedor given structure-that is, placedin context-and endowedwith meaning."I build on Glazer'sdefinitionby defining marketinformationas dataconcernedwith a firm's current and potential external stakeholders.Defined in this way, marketinformationrefers to externalinformationthat cuts across all functional areas of the firmratherthanthe more delimited "marketinginformation"thatsuggests it applies only to marketingdepartments.The sub-319stantive content of market informationis broad enough toinclude what is known as a result of experience and primary or secondaryresearchstudies. Moreover,informationcanarise from a variety of external sources (Barabbaand Zaltman 1991; Kohli and Jaworski1990).The premise of my researchis that the way an organization processes marketinformationis likely to be a functionof its organizationalsystems (Cyert and March 1992). AsHedberg(1981, p. 6) ndividuals,it wouldbe a mistaketo concludethatorganizationallearningis nothingbutthecumulativeresultoftheir members'learning.Organizationsdo not As individualsdevelop their personalities,personalhabits,and beliefs over time, scomeandgo, andmemoriespreleadershipchanges,but ms,andvalues overtime.This view argues that organizationscontain informationsystems(DaftandWeick 1984;SandelandsandStablein1987;Weick 1979). These systems involvepersonswho create,disseminate,andacton sharedmeanings,butwho aresubordinateto the system and its correspondingprocesses that represent"collectiveways of actingor thinking[that]have a realityoutside of the individualswho . conformto it" (Durkheim1938,cited in Walsh 1989, p. 15). This is also consistentwith theview that individual learning contributesto organizationallearning, but is an insufficientcondition for organizationallearning(Argyrisand Schon 1978; Sinkula1994).Four Key OrganizationalMarketInformationProcessesThe extant literaturehas consistently conceptualizedinformation activities as comprised of a series of processes.These views are found in literatureconcernedwith adoptionof innovations(Rogers 1983; Zaltman1979; Zaltman,Duncan, and Holbek 1973); information processing models(Lavidgeand Steiner 1961; Ray et al. 1973); informationutilization activities (Deshpand6 and Zaltman 1982, 1984;Menon and Varadarajan1992);organizationallearning(Day1991, 1994; Fiol and Lyles 1985; Huber 1991; Levitt andMarch1988); andthe sociology of science (AMA TaskForce1988; Knorr-Cetina 1981). Drawing on these researchstreams, four organizationalmarket informationprocessesare envisioned, half of which contain subprocesses:(1) informationacquisition;(2) informationtransmission;(3) conceptualutilization;and (4) itionprocesses. These processes referto the collection of primaryor secondaryinformationfromorganizational stakeholders. Information acquisition mayoccur,for example, throughformalmarketresearchsurveys,competitive intelligence activities, or customer satisfactionstudies; through informal collection of information fromsalespeople who interactwith customers;or from competitors who shareinformationat industryassociationmeetings.Information acquisition has been described as attention(Bettman 1979; Kahneman 1973) or awareness (Rogers1983) that has direction and intensity. In various organizational literatures, information acquisition has also beenThis content downloaded from 152.3.153.148 on Mon, 23 Sep 2013 16:33:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

320JOURNAL OF MARKETINGRESEARCH, AUGUST 1995termed intelligence generation(Kohli and Jaworski 1990),informationsearch (Weiss and Heide 1993), and initiation(Zaltman,Duncan, and Holbek 1973). All this literatureindicates that organizationalinformationacquisitionprocesses involve bringinginformationabout the externalenvironment into the boundary of the organization (Kiesler andSproull 1982; Starbuck1976; Weick 1969).Information transmission processes. These processesrefer to the degree to which informationis diffused amongrelevantusers within an organization(Beyer andTrice 1982;Glaser, Abelson, and Garrison 1983; Kohli and Jaworski1990). Informationtransmissionmay occur formally or informally (Dickson 1994; Mohr and Nevin 1990). Formaltransmissionis any type of organizedor structureddissemination, including policies, training sessions, research presentations,companymemoranda,meetings, and cross-functional teams (Narver and Slater 1990). Informal transmission occurs duringinterpersonalinteractions,such as casualconversationsinvolving marketinformation,or when organizational members educate one anotheron marketissues.Transmission may be top-down, down-up, or horizontal(Day 1991; Kohli and Jaworski1990).Conceptualutilizationprocesses. These processes refertothe indirect use of informationin strategy-relatedactions(Menon and Varadarajan1992; Rich 1981). Although theenactmentof conceptualutilizationprocesses often involvesbehaviors,the focus in these behaviorsis on influencingtheway organizationsprocess informationor their commitmentto it, which are more cognitive and affective in natureand,therefore, more indirect in their influence on marketingstrategies as compared with instrumentalutilization (described subsequently).Two subprocessesare proposed.First, information commitmentrefers to the extent towhich an organizationrecognizes the value of informationagents and products (Beyer and Trice 1982; Menon andVaradarajan1992). It is revealedwhen an organizationvalues informationas an aid to decision making, as opposed toconsidering it a disruption(an informal process), whereascommitmentto informationprovidersmay be found wheninformationprovidersreportto users at high organizationallevels (a formalprocess).Second, information processing refers to processes"throughwhich informationis given meaning" (Daft andWeick 1984, p. 294). Meaning is the result of "sensemaking" (Thomas, Clark, and Goia 1993), comprehending(Olson 1978), interpreting(Huber 1991), categorizing(Dutton and Jackson 1987; Jacksonand Dutton 1988), or elaboratingon evoked informationusing an organization'smemory (Hedberg 1981; Levitt and March 1988), collectiveschema (Dunn and Ginsberg 1986; Houston 1993), orsharedmentalmodel (Day 1991; Day andNedungadi 1994).This process is described by Dickson (1994, p. 46) as theconversion of marketintelligence "into knowledge and understandingwhen it is interpretedby, storedin, and changesthe decision makers'mental models of the marketenvironment." Informationprocessing may involve formal proceduresfor organizingandprocessinginformation,such as analytical models or playing devil's advocate, or more informal processes, such as team meetings in which interpretations of marketinformationare offered.Instrumentalutilizationprocesses. These processes referto the extent to which an organizationdirectly applies market informationto influence marketingstrategy-relatedactions. Three subprocessesare investigated:the use of information in (1) making, (2) implementing,and (3) evaluatingmarketingdecisions. Organizationaluse of informationindecision makingrefersto processes involving the integrationof informationsources and the selection among strategyalternatives(for a discussion of these processes at the individual level, see Bettman, Johnson, and Payne 1991; Cohen,Miniard, and Dickson 1980). This type of informationusehas been historicallyreportedto be very low (Weiss 1978).Thus, organizationalresearch has suggested that decisionmaking is not a distinct phase, but, rather,somethingthat is"muddledthrough"(Mintzberg, Raisinghani, and Theoret1976) or performedin a satisficing mode, which may limitinformationuse.Organizationaluse of informationin implementationprovides informationabout the enactmentof marketingstrategies to ensure the realizationof decisions. This process follows other research showing that implementationis facilitated by providing information regarding how decisionsshould be carried out (Leonard-Bartonand DeSchamps1988; Nutt 1986; Slevin and Pinto 1987). In contrast, Jaworski and Kohli (1993) describe marketresponsivenessasinvolving issues of whether and how quickly the firm responds to marketinformationin the design and implementation of marketingstrategies.Finally, organizationaluse of informationin evaluationrefers to processes for using market informationto determine positive and negative performanceoutcomes and thereasons for these outcomes (Zaltmanand Moorman 1989).In the diffusion of innovationsliterature,this is referredtoas the confirmationstage, because the focus is on assessingthe benefits of adoption (Rogers 1983). Evaluation,or performance feedback, has been described as being crucial tosuccessful organizationaladaptation(Fiol and Lyles 1985)and change (Argyris 1976). Therefore, organizationsthatuse marketinformationto evaluateoutcomes are more likely to develop effective "theories of action" (BarabbaandZaltman 1991).CONCEPTUALFRAMEWORKThis section links the four organizationalmarketinformation processes described in the previous section to certainnew productoutcomes and culturalantecedents.CulturalAntecedentsof onalcultureis definedby Deshpand6andWebster (1989, p. 4) as "thepatternof sharedvalues and beliefsthat help hatprovidenormsfor behaviorin the organization."Previous research indicates that organizationalculture affectsorganizationsin two ways. It can affect, first, the firm'schoice of outcomes and, second, the means to achieve theseoutcomes, including organizationalstructureand processes(Cameronand Freeman1991; Deshpande,Farley,and Webster 1993; Hatch 1993; Quinnand Rohrbaugh1983; Ruekert,Walker,and Roering 1985; Websterand Deshpand61990).This content downloaded from 152.3.153.148 on Mon, 23 Sep 2013 16:33:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

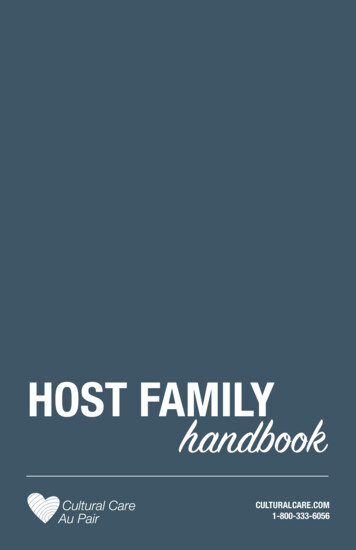

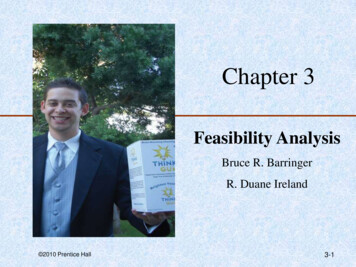

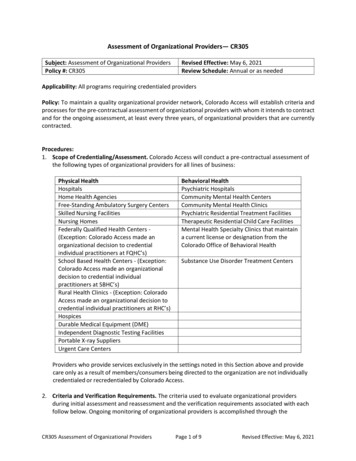

321Organizational Market Information ProcessesFigure 1PROCESSES*INFORMATIONMARKETOF ORGANIZATIONALANTECEDENTSCULTURALInternal Orientation( ) InformationTransmissionProcesses( ) ConceptualInformationUtilizationProcessesClan Culture(-) on( ) InformationUtilizationProcesses( ) on(-) InstrumentalHierarchyCulture(-) on(-) InformationUtilizationProcessesInformation(-) ConceptualInformationUtilizationProcesses(-) InstrumentalInformal GovernanceFormal Governance( ) Instrumental Information Utilization Processes( ) InformationAcquisitionProcesses( ) InformationTransmissionProcesses( ) Culture( ) es(-) InformationUtilizationProcesses(-) es(-) InstrumentalMarketCulture(-) es(-) InformationUtilizationProcesses(-) on( ) InstrumentalExternal Orientation( ) InformationAcquisitionProcesses( ) InstrumentalInformationUtilizationProcesses*( ) denotes that the cultureemphasizes the informationprocess.(-) denotes that the culturede-emphasizesthe informationprocess.To understandthe impact of cultureon organizationalinformationprocesses, the competing values model of cultureis adopted (Deshpand6, Farley, and Webster 1993; Quinn1988; Quinn and Rohrbaugh1983). Briefly, the model proposes two predominantdimensionsby which culturalvaluesvary.These two axes form a four-cell model of culture.Oneaxis, the informal-formaldimension, reflects preferencesabout the importance of organizational structure and involves a continuumfrom organic to mechanisticprocesses.The second axis, the internal-externaldimension,describeswhetherthe emphasis is on the maintenanceof an organization's internalsociotechnical system or the improvementofits competitive position within the external environment.The four cultures resulting from the intersectionof the twodimensions have been labeled adhocracies,markets,hierarchies, and clans.2 To determinehow these four cultures in2Some researchersuse similar terms to describe organi7ationalgovernance modes. In marketing,these four archetypeshave been used primarily by Deshpande,Farley,and Webster(1993) and Deshpand6and Webster(1988), who have referred to them as organizationalcultures. However,Ruekert,Walker,Roering (1985) referto them as governancemodes. In theorgani7ationalliterature,there is an entire stream of literaturecalled thecompeting values view that refers to these four types as organi7ationalcultures (e.g., Quinn and Rohrbaugh1983). Although other literaturehas discussed individual archetypes (see, for example, Mintzberg 1979; Ouchi1980; Williamson 1981), it is my preferenceto remainmost closely alignedwith the work of Deshpandeand the competing values literaturethat viewsthese four archetypesas organizationalcultures.fluence the emphasis placed on various organizationalmarket informationprocesses, I describe the focus of each endof the two axes and then discuss how the intersection ofthese axes producesan emphasison certaininformationprocesses. Figure 1 depicts the proposedview.Externally-focusedculturesversus internally-focusedcultures. Externally-focusedcultures will have better developed information acquisition and instrumentalutilizationprocesses, both of which involve interactionwith the external environment.Informationacquisitionprocesses involveenvironmentalscanning and intelligence activities and theimportationof the resulting informationinto the organization. Instrumentalutilizationprocesses entail the design andimplementationof marketingactions that influence on the other hand, have morewell-developed information transmission and conceptualutilizationprocesses, both of which function completely internalto the organization.Informationtransmissionprocesses involve dissemination of information among organizational members, whereas conceptual utilization processesemphasize increasingmembers'understandingof and commitmentto acquiredinformation.Formalcultures versus informalcultures.In general, formalizationhas been found to reducethe level of informationutilization in firms (Deshpande 1982; Deshpand6and Zaltman 1982). Offering a contrastingview, Zaltman,Duncan,This content downloaded from 152.3.153.148 on Mon, 23 Sep 2013 16:33:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

322JOURNAL OF MARKETINGRESEARCH, AUGUST 1995and Holbek (1973) make a finer distinction:Formalizationmay have opposite effects on different types of innovativebehavior, among which informationprocesses may be included (Zaltman1979). Specifically, Zaltman,Duncan, andHolbek (1973) suggest that formalized organizationsmayinterferewith the initiation stages of the adoption process(e.g., acquiring,understanding,becoming committed to aninnovation),but facilitate the implementationstages of theadoptionprocess (see also John and Martin1984; Kohli andJaworski1990). Previous researchhas generally not identified such findings because it has failed to distinguish between differenttypes of informationutilization.3Accordingly,it is arguedthat formalizedcultureswill facilitate instrumentalutilizationprocesses because these processes involve using informationto take marketingactions,while reducing informationacquisition, informationtransmission, and conceptualutilizationprocesses. If formal culturesreducethese processes, then logically it is inferredthatinformalcultures should foster informationacquisition,informationtransmission,and conceptualutilizationprocesses while also reducing instrumentalutilization processes.Otherresearchsupportsthis view by suggesting that informal organizationsfacilitate informationacquisition (Imai,Nonaka, and Takeuchi 1985; Zaltman 1979), 5; Menon andVaradarajan1992), and conceptual utilization (by weakening myopic interpretations,see Day 1991).A four cell model of organizational market informationprocesses. By combining the two previously describedaxesto form a four-cell model of differentcultures,it is possibleto determinethe degree to which each culturetends to emphasize or de-emphasize certain organizationalmarket informationprocesses. In makingthese determinations,a congruenceapproachis adopted,which focuses on the degree towhich the organization'sculturalvalues are mutually supportive of a firm's processes. When cultural values arealigned in this way, previous research suggests that correspondingorganizationalprocesses are more likely to be present and effective than when culturalvalues are not congruent (Cameronand Freeman 1991; Deal and Kennedy 1982;Nadler and Tushman 1980; Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1983;Ruekert,Walker,and Roering 1985; Williamson and Ouchi1981).To implementthe congruence approach,the two bordering axes for each cell in the previouslydescribedcompetingvalues frameworkare examined.As Figure 1 depicts, whenthe two axes indicate that similar information processesshould occur, the organizationshould emphasize these processes. However, when the value axes do not overlap andare, therefore, not mutually supportiveof certain information processes, it is hypothesized that the informationprocesses will be de-emphasized.I describe each culture andnote its focus on certainorganizationalinformationprocesses. Then, I offer a set of formalpropositions.3Theone exception,Jaworskiand Kohli's (1993) study,failed to find different effects for indicatorsof hierarchyon organizationaldesign responsiveness and organizationalimplementationresponsiveness.This may havebeen, in part, because implementationresponsiveness focused more ontimeliness of responsesthan the use of informationin implementation.Adhocracies value both flexibility and their competitiveposition in the external environment (Deshpande, Farley,and Webster 1993). Hence, they tend to emphasize entrepreneurship, creativity, and adaptability (Mintzberg1979). An adhocracy'svalue orientationsupportsonly thepresence of organizationalinformationacquisitionprocesses. Consistent with this view, Quinn (1988) notes that adhocraciestend to be effective at acquiringresourcesandperforming boundary spanning functions (see also Cameronand Freeman 1991); Quinn and Rohrbaugh(1983) suggestthat adhocraciestend to acquireinformationaboutthe environmentwhile emphasizingno otherinformationprocesses;and Slater and Narver (1994) note that entrepreneurialcultures such as adhocraciesthrive on informationacquisition(see Zammuto and Krakower 1991). Thus, organizationalinformation acquisition processes should be strong in adhocracies,thoughthe other informationprocesses should beweak or nonexistent.Markets emphasize goal achievement, productivity,andefficiency (Cameronand Freeman1991; Deshpand6,Farley,and Webster 1993), reflecting their externalorientationandvalue for formal governancesystems. These values supportthe presence of instrumentalutilization processes withoutsupportingany other informationprocess. Instrumentalutilization processes are consistent with markets' values because they involve using informationto influence a firm'seffectiveness in the environment (Denison and Spreitzer1991). Moreover, the norms characteristic of marketsnorms that rewardactions such as planning, objective setting, and evaluation(Quinn and Rohrbaugh1983)-reflectthe natureof instrumentalutilizationprocesses well. Therefore, organizational instrumental utilization processesshould be promoted within market cultures, whereas theother informationprocesses should be weak or nonexistent.Hierarchies emphasize order,uniformity,efficiency, certainty, stability, and control, reflecting internally orientedand formalized values (Deshpande, Farley, and Webster1993). The informationprocesses supportedby these valueaxes fail to overlapone another,suggesting that none of theinformation processes will be supported (see Figure 1;Quinn and Spreitzer1991). Consistentwith this, Lovell andTurner(1988, p. 414) suggest that hierarchiestend to forcea form of localized informationuse on the organizationbyrequiringthat "subunitshandle pieces of the organization'sproblems in relative independence."Likewise, hierarchiesare less likely to develop the person-to-personsystems crucial to informationprocesses (Patton 1978). Some researchdoes suggest that hierarchies are effective in the management and communication of information (Cameron andFreeman 1991; Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1983). However,other researchhas documentedthat hierarchiesdo not support organizational information transmission (Deshpandeand Kohli 1989; Jaworskiand Kohli 1993).Clans stress participation,teamwork, and cohesiveness(Ouchi 1980). The emphasisis on the developmentof sharedorganizationalunderstandingand commitmentthroughparticipative, as opposed to centralized, communication processes (Quinn 1988; Quinn and Rohrbaugh1983). Clan cultureshave been found to be high in trust,low in conflict, andlow in resistanceto change (Zammutoand Krakower1991).This content downloaded from 152.3.153.148 on Mon, 23 Sep 2013 16:33:02 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Organizational Market Information ProcessesFigure 1 indicates that informationtransmissionprocessesand conceptualutilizationprocesses are mutuallysupportedin this culture. In supportof this, Moorman,Zaltman, andDeshpande (1992) report that trust between informationproviders and users increases the amount of informationshared between parties. Acquisition processes and instrumental use processes, on the other hand, are focused on theexternalenvironment,which suggests they will not be emphasized in clans' internally-focusedcultures.Predictions.FromFigure 1, it is possible to predictwhichcultureswi

organizational information processes, it is unclear whether these processes have been measured at the organizational level. Second, unlike previous research, which has tended to focus on a subset of organizational information processes, I attempt to explicate a more complete conceptual domain for these processes.