Transcription

The importance of playDr David WhitebreadUniversity of CambridgeWith Marisol Basilio, Martina Kuvalja and Mohini VermaA report on the value of children’s play with a series of policy recommendationsWritten for Toy Industries of Europe (TIE)April 2012

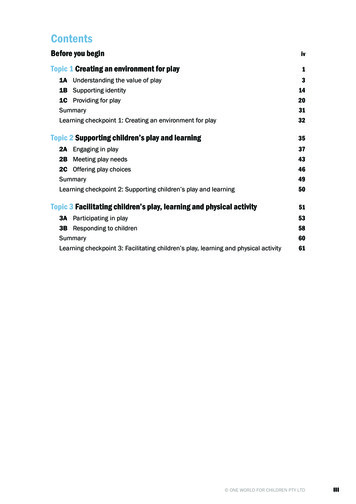

Table of ContentsPart 1. Aims of the Report . 3Part 2. Executive Summary . 5Authors and Contributors . 7Part 3. Review of Research . 83.1 Archeological, historical, anthropological and sociological research . 83.2 Evolutionary and psychological research . 133.3 The five types of play . 183.4 Environmental and social factors supporting or inhibiting play . 243.5 The consequences of play deprivation . 283.6 The work and views of European play researchers . 29Part 4. The work and views of European Play Organisations . 354.1 The work of European play organisations . 354.2 Views of European play organisations on issues related to children’s play . 37Part 5. Policy Review and Recommendations. 40Part 6. Bibliography . 482

Part 1. Aims of the Report‘Play’ is sometimes contrasted with ‘work’ and characterised as a type of activity which isessentially unimportant, trivial and lacking in any serious purpose. As such, it is seen assomething that children do because they are immature, and as something they will grow outof as they become adults. However, as this report is intended to demonstrate, this view ismistaken. Play in all its rich variety is one of the highest achievements of the human species,alongside language, culture and technology. Indeed, without play, none of these otherachievements would be possible. The value of play is increasingly recognised, by researchersand within the policy arena, for adults as well as children, as the evidence mounts of itsrelationship with intellectual achievement and emotional well-being.This report, however, focuses on the value of children’s play. It is a particularly importanttime for this to be recognised, as modern European societies face increasing challenges,including those that are economic, social and environmental. At the same time, theopportunities and support for children’s play, which is critical to their development of theabilities they will need as future citizens able to address these challenges, are themselvesunder threat. This arises from increasing urbanisation, from increasing stress in family life,and from changes in educational systems.Within the educational field, during recent decades the importance of high quality earlychildhood education has been increasingly recognised by the research community and bygovernments and policy makers throughout Europe and world-wide. However, the nature of‘high quality’ in this context has been contested. While in some European countries theemphasis continues to be upon providing young children with rich, stimulating experienceswithin a nurturing social context, increasingly in many countries within Europe and across theworld, an ‘earlier is better’ approach has been adopted, with an emphasis upon introducingyoung children at the earliest possible stage to the formal skills of literacy and numeracy. Thisis inimical to the provision and support for rich play opportunities. What is increasinglyrecognised within the research and policy communities, however, is that one vital ingredient3

in supporting healthy intellectual, emotional and social development in young children is theprovision of opportunities and the support for play.The purposes and functions of play in children’s development have been researched for wellover a century by thinkers and scientists from a range of disciplines. Part 3 of this reportprovides an overview of the range of research concerned with children’s play(anthropological, sociological, historical, psychological, educational) which has established thevalue of play for learning and development (and the consequences of a lack of playopportunities). This includes sections reviewing the research concerned with each of the fivemain types of play in which human children engage (physical play, play with objects, symbolicplay, pretence/socio-dramatic play and games with rules) and the implications of each area ofresearch for provision and policy. This part of the report concludes with a sectionsummarising the research, views and policy recommendations related to children’s play ofleading European play researchers.Alongside, and partly arising from, the increasing body of research evidence, there has been arecent and significant growth in the recognition of the importance of children’s play withinthe policy arena. The report recognises this in Part 4 which provides an overview of thegovernmental, professional and charitable organisations across Europe concerned with theprovision and enhancement of children’s play opportunities. This section includes a survey ofthe views of these leading stakeholders on the value of play for children’s learning anddevelopment, and of their policy recommendations.International bodies such as the United Nations and the European Union have begun toconsider and develop policies concerned with children’s right to play, with the educationaland societal benefits of play provision, and with the implications of this for leisure facilitiesand educational programs. The recognition of the need for further research in this area is alsodocumented. In Part 5, therefore, the report reviews these policy developments, includingexisting European policy, and makes further policy recommendations for play provision ineducational and non-educational contexts, and for beneficial research initiatives.4

Part 2. Executive Summary2.1The archaeological, historical, anthropological and sociological research into children’splay shows that play is ubiquitous in human societies, and that children’s play is supported byadults in all cultures by the manufacture of play equipment and toys. Different types of playare more or less emphasised, however, between cultures, based on attitudes to childhoodand to play, which are affected by social and economic circumstances.2.2In many ways, children’s right and opportunities for play are constrained withinmodern urbanised societies within Europe. This appears to be a consequence of theenvironmental ‘stressors’ of contemporary life, the development of a risk-averse society, theseparation from nature, and tensions within the educational arena, with an emphasis on‘earlier is better’.2.3The evolutionary and psychological evidence points to the crucial contribution of playin humans to our success as a highly adaptable species. Playfulness is strongly related tocognitive development and emotional well-being. The mechanisms underlying theserelationships appear to involve play’s role in the development of linguistic and otherrepresentational abilities, and its support for the development of metacognitive and selfregulatory abilities.2.4Psychological research has established that there are five fundamental types of humanplay, commonly referred to as physical play, play with objects, symbolic play, pretence orsocio-dramatic play, and games with rules. Each supports a range of cognitive and emotionaldevelopments, and a good balance of play experience is regarded as a healthy play diet forchildren. Some types of play are more fully researched than others, and much remains to beunderstood concerning the underlying psychological processes involved.2.5Children vary in the degree to which they are playful, and have opportunities to play.Playful children are securely attached emotionally to significant adults. Poverty and urbanliving, resulting in stressed parenting and lack of access to natural and outdoor environments,5

can lead to relative play deprivation. At the same time, children brought up in relativelyaffluent households may be over-scheduled and over-supervised as a consequence ofperceptions of urban environments as dangerous for children, and a growing culture of riskaverse parenting. Children suffering from severe play deprivation suffer abnormalities inneurological development; however, the provision of play opportunities can at least partiallyremediate the situation.2.6Leading play researchers from eight European countries were consulted about theirwork and their views on the important aspects of play for learning and development. Whilethere were differences in emphasis, there was general consensus that play is difficult todefine, that it is not the only context for children’s learning, but makes unique and beneficialcontributions, that play provision is under threat in Europe, and that there are dangers butalso contributions from screen-based play. The role of adults in supporting children’s play iscomplex, often poorly executed and counter-productive, and different views were expressed.This is an area which would benefit from further research.2.7Organisations supporting and advocating children’s play from across Europe were alsoconsulted, with twelve representative bodies responding to a survey of their work, their viewson the nature and value of children’s play, and on the extent and quality of current provision.Perhaps not surprisingly, there was widespread support for the value of play and extensiveevidence of poor provision. At the same time, numerous examples were provided ofinitiatives which were significantly enhancing opportunities for high quality play experiencesin different parts of Europe.2.8The report acknowledges the work of the European Commission and Council intheir development of policies supporting provision for children’s play. For example, on 12May 2011, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on Early Years Learning in theEuropean Union, which notes that the early years of childhood are critical for children’sdevelopment and highlights that ‘in addition to education, all children have the right to rest,leisure and play’.6

2.9It makes four recommendations for more detailed policies which could be developed,with advantage, by the European Union, which are supported by the research evidence andthe expert views of the play researchers and organisations consulted. These are as follows: Promote awareness and change attitudes regarding children’s play Encourage improved provisions of time and space for children’s play Support arrangements enabling children to experience risk and develop resiliencethrough play Establish funding agencies that promote play and play researchAuthors and ContributorsThis report has been researched and written by Dr David Whitebread, a Senior Lecturer inPsychology and Education at the University of Cambridge, UK, together with two of his PhDstudents, Martina Kuvalja and Mohini Verma, and a post-doctoral researcher, Marisol Basilio.The latter are each conducting research into aspects of young children’s play and learning. DrWhitebread is an expert in the cognitive development of young children and in earlychildhood education. He has published extensively in relation to children’s learning anddevelopment, and the role of play in these processes. His most recent publication isDevelopmental Psychology and Early Childhood Education (Sage, 2012).The authors would like to thank the European play researchers and play organisations whocontributed information and views which have informed this report. The former are listed onp. 31, and the latter on pp. 36-7.7

Part 3. Review of ResearchThis part of the report presents a literature review of research concerned with thephenomenon of play. Extensive research has been conducted concerning the nature andpurposes of play within a wide range of academic disciplines. The role of play in relation to itscontexts within human societies has been addressed within archaeological, historical,anthropological and sociological research, and this work is addressed in the first section(section 3.1.) of this review below. Following this, section 3.2 addresses the research whichhas attempted to understand the psychological processes through which play impacts directlyupon individual learning and development. The following three sections (sections 3.3 – 3.5)set out the research related to the now established five general play types, the environmentalfactors which support or inhibit play, and the consequences of play deprivation.As part of the process of putting together this review, a number of leading play researchersfrom across Europe and across disciplines were specifically consulted. They were asked toprovide a brief report indicating the nature of their research contribution, together with theirviews on significant factors influencing the contribution of play to children’s learning anddevelopment, the consequences of a lack of provision, and their policy recommendations.The information and views they submitted are summarised in the final section of this review(section 3.6).3.1 Archaeological, historical, anthropological and sociological researchThe study of play through time and across cultures has consistently demonstrated twocharacteristic features of play in human societies. First, it is clear that play is ubiquitousamong humans, both as children and as adults, and that children’s play is consistentlysupported by adults in all societies and cultures, most clearly in the manufacture of playequipment and toys. Second, it emerges that play is a multi-faceted phenomenon, with avariety of types that appear in all societies, but that there are variations in the prevalenceand forms that the various types of play take in different societies. These variations appearto arise from differing attitudes concerning the nature of childhood and the value of play.8

Archaeological and cross-cultural records indicate the prevalence of play and games sinceprehistoric times, supported by the existence of dice, gaming sticks, gaming boards andvarious forms of ball-play material made of stones, sticks and bones from the PalaeolithicEra (Fox, 1977; Schaefer and Reid, 2001). Excavations in ancient China, Peru, Mesopotamiaand Egypt have revealed miniature models made of pottery and metal, most probably usedas toys for children and drawings showing depictions of people playing and play objects suchas tops, dolls and rattles (Frost, 2010).Within historical times, studies of the nature of childhood within European cultures haverevealed a remarkably consistent picture (Ariès, 1996, Cunningham, 2005). Thus, in theclassical societies of ancient Greece and Rome, children’s play was clearly valued and theseeds of many modern views on play can be discerned. Plato (427 – 347 BC), for example,advocated the use of free-play, gymnastics, music and various other forms of leisurelyactivities as means of developing skills for adult life, as well as supporting health andphysical development. Aristotle (384 – 322 BC) also emphasised the value of play andphysical activities for the overall development of the child. Roman thinkers such asQuintilian (35-97 AD) recommended the use of play as the earliest form of instruction.Historians (Wiedemann, 1989; Golden, 1993), when trying to reconstruct the life of childrenin these ancient societies, have found play to be the characteristic feature of childhood,with children enjoying great autonomy in the sphere of play.A similar picture emerges in studies of childhood throughout medieval Europe and into theperiod of the Reformation and Renaissance (Hanawalt, 1995; Orme, 2001). Ideas such asdevelopmentally appropriate education, play-based pedagogy, learning through first-handexperience, the importance of vigorous play for healthy development and adultparticipation in children’s play can be seen clearly articulated by the thinkers and educatorsof these times, including Martin Luther, John Amos Comenius and John Locke. In themodern era proponents of early childhood education such as Rousseau, Pestalozzi andFroebel advocated similar ideas, and in some cases implemented them in their owneducational centres (e.g.: Pestalozzi’s Institute for children in Switzerland established in1805 and the first ‘kindergarten’ started by Froebel in Germany in 1837). Froebel was alsothe first to use the term ‘playground’ to describe play environments developed by adults for9

children.Within the twentieth century, renowned folklorists Iona and Peter Opie’s encyclopaedicstudies of British children’s folklore, language, nursery rhymes and games (Opie and Opie,1952; 1959) demonstrated that children were singing, playing and talking with each other inthe same manner as their predecessors over a century ago, and across the English-speakingworld. More recent reviews of these collections furthermore, have documented thecontinuation of these traditions until today and across continents (Warner, 2001).Anthropologists have studied children’s play in a wide variety of cultures and, increasingly inthe modern world, with the increase in levels of immigration, in sub-cultures withinsocieties. The cultures studied include those that are ancient and technologically primitive,such as Mayan culture in Mexico (Gaskins, 2000), cultures in the developing world, such asMalaysia (Choo, Xu and Haron, 2011) and Puerto Rico (Trawick-Smith, 2010), and modern,urbanised, technologically advanced cultures, such as Italy (Bornstein, Venuti and Hahn,2002). Several studies have compared play across cultures or sub-cultures, in relation tocultural attitudes and practices. Cote and Bornstein (2009), for example, have reported anumber of studies comparing play and attitudes to play amongst mothers and youngchildren in Japanese, South American and European immigrant sub-cultures in the UnitedStates.A number of clear and consistent patterns emerge from these studies. All five types of playin which human children engage (physical play, play with objects, symbolic play,pretence/sociodramatic play and games with rules) are found in different manifestations,depending on available technology, in all cultures. However, there are variations betweencultures and subcultures in attitudes to children’s play, arising from cultural values aboutchildhood, gender and our relations with the natural world often linked to economicconditions, religious beliefs, social structures and so on. Cultural attitudes, transmitted tothe children predominantly through the behaviour of their parents, affect how much play isencouraged and supported, to what age individuals are regarded as children who areexpected to play, and the extent to which adults play with children.10

Attitudes to gender in different cultures also impact upon children’s play. In cultures inwhich there is rigid separation between adult male and female roles boys and girls areprepared for these roles through the toys and games provided, with boys play often beingmore competitive, physical and dangerous and girls play being more focused on their futuredomestic role, involving play with household objects, such as pots and pans, tea-sets, anddolls. Historically, children in all cultures have played extensively in their naturalenvironments. In modern, urbanised societies, however, the natural environment is oftenseen as remote and dangerous for children, so specially designed playgrounds and parks areseen as more appropriate play spaces.Gaskins, Haight and Lancy (2007) have identified three general cultural perceptions or viewsof play which seem to have a significant impact on the pattern of children’s play, and thelevel of involvement of their parents, as follows: ‘Culturally curtailed play’ – in some pre-industrial societies play is tolerated butviewed as being of limited value and certain types of play are culturally discouraged.For example, in Gaskins (2000) study of the Mayan people in the Yucatan she foundthat pretence involving any kind of fiction or fantasy was regarded as telling lies. ‘Culturally accepted play’ – in pre-industrial societies parents expect children to playand view it as useful to keep the children busy and out of the way, until they are oldenough to be useful, but they do not encourage it or generally participate in it.Consequently the children play more with other children unsupervised by adults, inspaces not especially structured for play, and with naturally available objects ratherthan manufactured toys. ‘Culturally cultivated play’ – middle-class Euro-American families tend to view play asthe child’s work; play is encouraged and adults view it as important to play with theirchildren. The children also often spend time with professional carers, who view it asan important part of their role to play with the children to encourage learning. Thestyle and content of this involvement varies, however; a study of mothers in Taiwanfound that they directed the play much more than Euro - American parents and11

focused on socially acceptable behaviour, rather than encouraging the child’sindependence.When we look at the contemporary situation in 21st century Europe, it is clear that the finalgeneral view of ‘culturally cultivated play’ generally prevails. At the same time, however, itis clear that there are variations even within Europe, and that there are tensions betweenmany parents’ views and the opportunities they are able to afford their children. Twoparticular issues emerge related to attitudes to children’s safety and risk, and to the amountof time parents are able to devote to playing with their children.A currently emerging cultural difference within modern Euro-American societies involvesattitudes to risk; in the heavily urbanised UK, for example, the culture is currently quite riskaverse, and so children are heavily supervised and play indoors, in their gardens and inspecially designed play spaces with safety surfaces. In the more rural and thinly populatedScandinavian countries, however, children are much more encouraged to play outdoors andin natural surroundings, and are far less closely supervised. At the same time, many parentsacross the developed countries of the world have reported in a number of surveys that theyfeel they do not have sufficient time to play with their children. This was a clear finding, forexample, of a survey carried out by the LEGO Learning Institute (2000) of parents in France,Germany, the UK, Japan and the USA.The evidence suggests that modern, urbanised life styles often result in a pattern wherebychildren are much more heavily scheduled during their leisure time than was the case in therecent past. Lester and Russell (2010), in a major review of research examining children’scontemporary play opportunities worldwide, provide a very useful and compelling review ofthe environmental ‘stressors’ in modern life, associated with increasing urbanisation, whichimpact negatively on children’s play experiences. Within this, they make the telling pointthat half the world’s children will very soon be living in cities. The concern of manycommentators is that the resulting pattern of children being over-supervised and overscheduled, with decreasing amounts of time to play with their peers or parents, is likely tohave an adverse effect on children’s independence skills, their resourcefulness and thewhole range of developmental benefits which we document in the following section. In the12

LEGO Learning Institute (2000) study a review of newspapers and periodicals demonstratedthat there have been extensive debates about this issue in the public press from at least themid 1990s onwards. Many parents, in their response to the survey they completed,indicated clearly that they recognise these problems in their own lives, and would verymuch welcome the opportunity to provide improved quality of play experiences for theirchildren.There are also currently tensions within the educational arena. Over the last ten to twentyyears, the curriculum for early childhood and primary education has been increasinglyprescribed by governments. While these have avowed the value of children learningthrough play, this has been systematically limited to children under the age of six to sevenyears of age. While there are many beacons of excellence, what play provision there iswithin educational contexts across Europe is also often ineffectively supported byinadequately trained staff. As a consequence, there has been a plethora of books publishedrecently by early childhood educationalists and developmental psychologists setting out thevalue of play for children’s learning and development (see, for example, Moyles, 2010;Broadhead, Howard and Wood, 2010, Whitebread, 2011). At the same time, however, thesepublications consistently document the difficulties early years practitioners have indeveloping effective practice to support children’s learning through play, largelyexacerbated by pressures to ‘cover’ the prescribed curriculum, meet government imposedstandards etc. Combined with the curbs on children’s free play opportunities identifiedwithin the home context above, this leads to a worrying picture overall of children acrossEurope and the rest of the developed world with increasingly limited opportunities for thefree play and association with their peers which were so commonly available only ageneration or two ago to their parents and grandparents. Chudakoff (2007), for example,has documented the sharp decline in children’s free play with other children across the‘Western’ world.3.2 Evolutionary and psychological researchPsychologists have been researching and theorising about play and its role in developmentfor well over a century. However, partly because of its highly multi-faceted nature and the13

fact that it is an intrinsically spontaneous and unpredictable phenomenon, it has proved tobe extremely difficult to define and to research. As a consequence, whilst it is almostuniversally accepted that children benefit from play opportunities, and particularly stronglysupported amongst the early childhood professional community, realising the fulldevelopmental and educational potential of play in practice has proved illusive. However,there has been a considerable resurgence in research on children’s play in recent yearswhich gives us a much clearer view of the nature of play, of its purposes and the processesby which it influences development and learning. In turn, these more recent analysesprovide very clear guidelines as to the nature of provision for play that is required to allowour young children to flourish in all aspects of development.The evidence for the developmental benefits of play is actually now overwhelming. There isalso an emerging consensus as to the various types of play and their developmentalsignificance. This new position arises partly from the surge of evidence arising in the lastfew decades from evolutionary psychology. It has been recognised for some time that,through evolution, as more and more complex animals evolved, the size of their brainsincreased, and this was associated with increasingly longer periods of biological immaturity(i.e. the length of time the young were cared for by their parents), paralleled by increasingplayfulness (Bruner, 1972).Thus, as mammals evolved into primates, and as primates evolved into humans, there wasan increase in problem-solving abilities allowing greater ‘tool use’ and an increase in‘representational’ abilities supporting the development of language and thought. Parallelingthis, in mammals we see the emergence of physical play (mostly ‘rough and tumble’); inprimates we see ‘play with objects’ developing and simple tool use, and in humans we seethe emergence of ‘symbolic’ forms of play (including verbal and artistic expression,pretence, role-play and games with rules) which depend upon our ‘symbolic’ abilities suchas language. This analysis of the evolution of play, and its most glorious manifestation inhumans, has led researchers in this area to argue that playfulness is fundamental to thedevelopment of uniquely human abilities. Pellegrini (2009), for example, has concludedthat, in animals and humans, play (as opposed to ‘work’) contexts free individuals to focuson ‘means’ rather than ‘ends’. Unfettered from the instrumental constraints of the work14

context, where you have to get something done, in play the individual can try out newbehaviours, exaggerate, modify, abbreviate or change the sequence of behaviours,endlessly repeat slight variations of behaviours, and so on. It is this characteristic of play, itis argued, that gives it a vital role in the development of problem-solving skills in primates,and the whole gamut of higher-order cognitive and social-emotional skills developed byhumans. The evolutionary perspective has thus contributed significantly to the emergingconsensus around the psychological functions of play and an agreed typology of play basedon its adaptive psychological functions (which we detail below).Powerful evidence supporting this view of the role of play in human functioning has alsoemerged within recent developmental psychology. Here, recent studies using a range ofn

play shows that play is ubiquitous in human societies, and that children's play is supported by adults in all cultures by the manufacture of play equipment and toys. Different types of play are more or less emphasised, however, between cultures, based on attitudes to childhood and to play, which are affected by social and economic circumstances.