Transcription

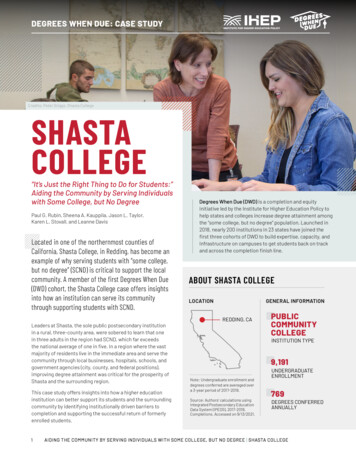

DEGREES WHEN DUE: CASE STUDYCredits: Peter Griggs, Shasta CollegeSHASTACOLLEGE“It’s Just the Right Thing to Do for Students:”Aiding the Community by Serving Individualswith Some College, but No DegreePaul G. Rubin, Sheena A. Kauppila, Jason L. Taylor,Karen L. Stovall, and Leanne DavisLocated in one of the northernmost counties ofCalifornia, Shasta College, in Redding, has become anexample of why serving students with “some college,but no degree” (SCND) is critical to support the localcommunity. A member of the first Degrees When Due(DWD) cohort, the Shasta College case offers insightsinto how an institution can serve its communitythrough supporting students with SCND.Leaders at Shasta, the sole public postsecondary institutionin a rural, three-county area, were sobered to learn that onein three adults in the region had SCND, which far exceedsthe national average of one in five. In a region where the vastmajority of residents live in the immediate area and serve thecommunity through local businesses, hospitals, schools, andgovernment agencies (city, county, and federal positions),improving degree attainment was critical for the prosperity ofShasta and the surrounding region.This case study offers insights into how a higher educationinstitution can better support its students and the surroundingcommunity by identifying institutionally driven barriers tocompletion and supporting the successful return of formerlyenrolled students.1Degrees When Due (DWD) is a completion and equityinitiative led by the Institute for Higher Education Policy tohelp states and colleges increase degree attainment amongthe “some college, but no degree” population. Launched in2018, nearly 200 institutions in 23 states have joined thefirst three cohorts of DWD to build expertise, capacity, andinfrastructure on campuses to get students back on trackand across the completion finish line.ABOUT SHASTA COLLEGELOCATIONGENERAL INFORMATIONREDDING, CAPUBLICCOMMUNITYCOLLEGEINSTITUTION TYPE9,191Note: Undergraduate enrollment anddegrees conferred are averaged overa 3-year period of 2017-2019.Source: Authors’ calculations usingIntegrated Postsecondary EducationData System (IPEDS), 2017-2019,Completions. Accessed on 9/13/2021.UNDERGRADUATEENROLLMENT769DEGREES CONFERREDANNUALLYAIDING THE COMMUNITY BY SERVING INDIVIDUALS WITH SOME COLLEGE, BUT NO DEGREE SHASTA COLLEGE

Credits: Shawn Spence Photography, LuminaFoundation Focus MagazineIN A REGION WHERE THE VAST MAJORITY OF RESIDENTSLIVE IN THE IMMEDIATE AREA AND SERVE THE COMMUNITYTHROUGH LOCAL BUSINESSES, HOSPITALS, SCHOOLS, ANDGOVERNMENT AGENCIES (CITY, COUNTY, AND FEDERALPOSITIONS), IMPROVING DEGREE ATTAINMENT WASCRITICAL FOR THE PROSPERITY OF SHASTAAND THE SURROUNDING REGION.Credits: Shasta CollegeWHAT MOTIVATED PARTICIPATION IN DWD?Shasta College decided to join DWDbased on three related factors: aninstitutional awareness of the need toserve the SCND population to address thelocal community’s social and economicconditions; strong institutional leadershipsupport for DWD strategies; andmomentum from existing programs.DWD PROVIDED A PLAN TO ADDRESS THE LOCALCOMMUNITY’S SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CONDITIONSAs one Shasta leader explained, “there isn’t a college-goingculture” in the area. The local economy has focused heavilyon resource extraction jobs such as mining and logging, andpeople who live there could find economic security with nopostsecondary education. Shasta leaders acknowledgedthis economic context and noted that education beyondhigh school was never a priority for local residents. Leadingup to their DWD participation, college leaders expected therecruitment and reenrollment of former students with credit tobe a difficult task.Despite this context, Shasta leaders knew that DWD effortswere critical to improve social and economic conditions in theregion. As outlined by one Shasta leader, the region is “often inthe top five, or at least the top 10, in all sorts of public healthstatistics such as highest rates of smoking, highest rates of2AIDING THE COMMUNITY BY SERVING INDIVIDUALS WITH SOME COLLEGE, BUT NO DEGREE SHASTA COLLEGE

obesity, highest rates of domestic abuse, highest rates of diabetes, andhighest rates of adverse childhood experiences.” This person explainedthat “our public health department would argue that our regional collectivework began by linking all of these public health issues with educationallevel—or the lack of educational attainment—and that our lower educationalattainment is dramatically affecting our health.” Consequently, Shastaleaders viewed the decision to join DWD and support the SCND populationas a first step to shift this educational culture, which could lead to morepositive community economic and health outcomes.INSTITUTIONAL LEADERSHIP STRONGLY SUPPORTED SHASTA’SPARTICIPATION IN DWDA second factor that prompted Shasta’s participation in DWD was thevocal support of institutional leadership and the acknowledgment of theinitiative’s value by other stakeholders. One Shasta leader stated that“Two key people—particularly, our college president and our VPof instruction—were really champions behind this effort . . . andthen the rest of our leadership team really has embraced itwholeheartedly and our deans are on board.”Top institutional leadership understood the value of DWD because degreereclamation policies are student-friendly policies. Indeed, the presidentoften communicated in meetings with staff that Shasta joined DWD notbecause of potential financial incentives for conferring more degrees, butbecause “it’s just the right thing to do for students.”In fact, Shasta College’s leadership is so supportive of improvingopportunities for the SCND population that it has written degreereclamation into the institutional strategic plan. Specifically, under GoalOne, which focuses on using “innovative best practices” to increase the ratethat students complete their degrees and transfer requirements, ShastaCollege’s 2018–21 strategic plan says that the institution will: “Implementbest practices to proactively confer degrees and certificates to studentsfor the work that has been completed including degree audits, “degreereclamation” and “opt-out” degree conferral.”1One prominent member of Shasta College’s leadership team oftenmentioned the influence of Dr. Kate Mahar, Dean of Innovation and StrategicInitiatives (and DWD team member), on the institution’s decision to joinDWD. Another Shasta leader noted that Dean Mahar was always “pushingfor these sorts of ideas . . . and she was involved in the strategic planningprocess with our college council and our leadership.” Leaders said thatMahar was the first to approach the college regarding DWD. Oneleader recalled that Mahar told them, “‘We have an opportunity toparticipate in this pilot project’ . . . [and] after she explained theconcept and asked if we were interested, I said, ‘why wouldn’t we be?’”Shasta leaders recognized the importance of serving the SCNDpopulation and the institution committed to implementing DWDstrategies that recognize the unique barriers this population facesand the potential changes needed to best serve it.1. Activity E under Institutional Objective 1.2, Shasta College 2018 – 2021 StrategicPlan. Retrieved from ITION OF DEGREE RECLAMATIONDegree reclamation is an equity-focusedand evidence-based approach to boostdegree attainment among potentialcompleters and “some college, but nodegree” populations.Institutions and systems deploydegree reclamation strategies to helppotential completers—students whohave accumulated roughly two or moreacademic years’ worth of credit andhave stopped out of an institutionor transferred from a two-year to afour-year institution before receivinga degree—attain degrees that aremeaningful to their education andcareer goals.Through degree reclamation, institutionsalso reengage the “some college, but nodegree” population, and provide thesestudents with targeted supports towardcompletion of associate’s degrees, andaward degrees when sufficient creditsare earned.In short, degree reclamation ensuresthat earned but unawarded degreesaren’t left on the table and that studentswho are just a few credits shy of adegree are supported all the way acrossthe finish line.Shasta leaders recognized theimportance of serving the SCNDpopulation and the institution committedto implementing DWD strategies thatrecognize the unique barriers thispopulation faces and the potentialchanges needed to best serve it.AIDING THE COMMUNITY BY SERVING INDIVIDUALS WITH SOME COLLEGE, BUT NO DEGREE SHASTA COLLEGE

MOMENTUM FROM EXISTING PROGRAMS ALIGNED WITH DWD GOALSWHAT IS THE ACE PROGRAM?A third factor that led to Shasta’s involvement and success in DWD was the institution’sability to align it with existing efforts and opportunities to support the SCND population,including work with the Lumina Foundation-funded and Institute for Higher EducationPolicy-led (IHEP) Talent Hub. Through this Talent Hub work, Shasta College becameacquainted with the high proportion of SCND individuals in its region which, in turn,convinced it to join the DWD initiative.The ACE program is designedfor people who want tocontinue working, attendcollege full-time, needpredictable schedules, andare ready to take college-levelcoursework by the time theprogram begins. The programfeatures compressed classesthat are hybrid (in-person plusonline instruction) as wellas fully online. The structureallows a student to completetheir certificate or degreewithin four to 24 months.Shasta leaders recognized that the average age of residents in the region was olderthan the rest of the state, suggesting that degree reclamation efforts would be key toboosting degree attainment, given the limited number of traditionally aged collegestudents in the region. As one Shasta official explained, “we really got excited about howmany people [DWD] could help in our region and what that could look like.” With supportfrom leadership, Shasta’s DWD team accounted for existing programs and initiativescurrently underway when considering how the new initiative could align with otherprograms and the broader goals of the institution.If students identified through DWD needed additional coursework, Shasta leveragedits accelerated degree program known as ACE (Accelerated College Education), anadult completion program (see sidebar). ACE and its director, Buffy Tanner, have gainednational attention for early success in serving adult learners, leading Shasta leadersto agree that ACE would be an ideal avenue to help SCND students complete their finalcredits to attain a degree. One leader said:Our ACE program is so strong and to be able to reach out and say, “did you know howclose you were? Come on back.” And we have this great place to bring them back tothanks to [Buffy Tanner]. . . . One of the things that I have always said is, you can’t inviteadults back to the program they left in the first place; [in] targeting them [it’s importantto note that] “it’s different, you’re different, come on back.”Many adult students are working and/or have family care responsibilities, and ACEprovides an avenue for them to complete their degrees on an expedited timeline andwith a format conducive to their scheduling needs.Credits: Peter Griggs, Shasta College4AIDING THE COMMUNITY BY SERVING INDIVIDUALS WITH SOME COLLEGE, BUT NO DEGREE SHASTA COLLEGE

ENGAGEMENT AND EXPERIENCEWITH DEGREES WHEN DUEAfter joining DWD’s first cohort in October 2018, Shasta College organized its DWDwork into four primary categories that are described in detail below: establishinga DWD team and DWD leadership; identifying award-eligible students and auditingdegrees; engaging students; and sustaining degree reclamation strategies.ESTABLISHING A DWD TEAM AND DWD LEADERSHIPBefore beginning DWD work, Shasta College securedadditional funding to devote to the initiative and, usingLumina funds, hired a coordinator for DWD who worked threeto five hours a week. The college developed a cross-functionalteam based on the guidance included in the DWD learningmanagement system (LMS). The team included the associatevice president of student services, dean of educationaltechnology and research, counseling staff, associate dean offinancial aid and admissions, transfer evaluator, ACE director,academic deans, a faculty member, and marketing andinformation technology staff. The goal of creating the teamwas to convene the diverse expertise needed to locate andcontact stopped-out students and ensure returning studentswould have a transition back to postsecondary education withthe fewest barriers.The coordinator served as Shasta’s DWD team lead. Shasta’sleaders attributed the momentum of the team’s work to thecoordinator. One of Shasta’s leaders reflected on how theproject progressed and highlighted her critical role:One team member said:I think our DWD team relied on the campus lead to serve as acoordinator. We relied on her being that linchpin between theproject’s bigger processes and . . . what the group needs to do.Each member could then go complete the piece they need tocomplete and come back together and feed that all throughour team lead.Given the many responsibilities of community collegeadministrators, Shasta’s decision to identify a clear teamlead to coordinate DWD activities was critical. This singleindividual in charge of triaging DWD work to the appropriatearea allowed the institution to remain organized and on-task.And although the DWD team lead coordinated the initiative’sday-to-day operations, it was the diverse expertise of thecross-functional team that allowed Shasta to move itswork forward.She herds the cats—looking at who we want to target andthen completing the data analysis; she really helps with thatlogistic support. She’s also the primary person that interactswith the DWD learning management system portal and thenwe work together on areas where we’re stumped.Several team members said that having a campus lead whoseprimary role was to support the DWD initiative was critical toensuring progress. It was the DWD team lead who most oftenparticipated in official activities, disseminated takeaways tothe team, and helped ensure the tasks were complete and theinitiative was progressing at an appropriate pace.Credits: Shawn Spence Photography, Lumina Foundation Focus Magazine5AIDING THE COMMUNITY BY SERVING INDIVIDUALS WITH SOME COLLEGE, BUT NO DEGREE SHASTA COLLEGE5

IDENTIFYING AWARD-ELIGIBLE STUDENTS ANDAUDITING DEGREESNEARLY HALF OF TARGETED STUDENTS HADALREADY COMPLETED A DEGREETo implement DWD, Shasta College first established how itwould identify its stopped-out population, including the timeof last enrollment, the degrees against which transcriptswould be audited for eligibility, and other institutional policiesthat might limit the completion of a degree in a timely fashion(e.g., credit residency requirements or credit expiration).Shasta College decided to identify students enrolled betweenfall 2013 and spring 2018, who had at least 45 credits, and whohad a GPA of at least 2.0. Although Shasta does not have acredit expiration policy, it does require at least 12 creditsto be completed at the institution to fulfill the creditresidency requirement.Shasta identified 575 former students who hadstopped out but had accumulated 60 or morecredits,2 and almost half—252—of these studentshad completed all the academic requirementsfor a degree. After contacting students, Shastaawarded degrees to 250 of them.Based on these factors, the IT department generated a listof over 4,500 students. However, Shasta College did nothave the capacity to conduct batch degree audits on studenttranscripts, so team members would need to manuallycompare former students’ coursework with existing academicprograms to determine degree eligibility. Because thisprocess is time-consuming, the DWD team needed to limit theinitial group of transcripts to review.The team decided to focus on a subset of 575 students. Asexplained by a Shasta leader, this population “had 60 unitsor more when they left with no degree or certificate, and . . .they took the courses that would have tended to transfer” viathe California State University General Education Breadthrequirements. More specifically, Shasta focused on thesubset of students who had already completed transfer-levelmath, English, and communications courses, as well as acritical thinking class. As one DWD team member remarked,“if students have gone through the trouble of completing thoseparticular four classes, especially the math course . . . this isthe low hanging fruit group” that would be most likelyto be eligible for a degree or willing to return to completeremaining credits.Even with this more limited group of students to review, astaff member could only review the transcripts of 25 to 50former students per week, because all audits were conductedmanually. But even though the degree auditing process wascumbersome, the team saw early successes that supportedcontinued work. One DWD team member noted that “out of thefirst 175 student transcripts that were analyzed, about a thirdalready had a degree that was never awarded.”62. Students in this group accumulated an average of 79.63 credits, with aminimum of 51 credits accumulated and maximum of 206. Three studentsin this group fell below 60 credits accumulated (51, 54, 57).Figure 1.Targeted Former Students and Subsequent Outcomes0.34%Students Completed all theAcademic Requirements,But Not Awarded Degree43.5%Students Completed all theAcademic Requirements,And Awarded Degree56.2%Students’ AcademicRequirements IncompleteNote: Targeted students had stopped out but had accumulated 60 or more credits.AIDING THE COMMUNITY BY SERVING INDIVIDUALS WITH SOME COLLEGE, BUT NO DEGREE SHASTA COLLEGE

ENGAGING STUDENTSThe early results of student degree eligibility work supportedShasta’s position that the SCND population was a criticalgroup to reengage. However, staff needed to makewell-planned decisions regarding communicating withstudents about degree eligibility as well as mechanisms tohelp near-completers complete their degree.Clear and responsive communication was key. Shastaleaders decided it was essential to establish a centralizedcommunication point with a dedicated phone line, email,and website to which all students in this population could bedirected. As one DWD team member explained, “we’re goingto get one shot at this, and if we put them through any hoop,if they sit on the phone, or if we don’t return their message,they’re gone.”In order to streamline communication, the college adoptedan opt-out consent approach for students who already metthe degree requirements for a credential. A Shasta leaderexplained the communication script: “one states, ‘Hey, wetook another look at your records and you did earn a degree.We’ve posted it to your transcripts. Reach out and let us knowwhat address you want your diploma to be sent to. If you don’twant your degree, please call us and let us know.’” Shastacommunicated to students that it planned to post the degreeto their transcripts and recommended that students updatetheir resumes. Shasta also invited students to graduation ifthey wanted to walk at graduation and celebratetheir success.For near-completer students who still needed to finishcredits, Shasta leaders focused on communicating the newopportunities available through the ACE program. Shastawould explain the number and type of courses that studentswere missing and advise them to consider the ACE program.ACE offers year-round classes including an eight-week summersession and two eight-week sessions in both the fall and springsemesters. ACE schedules classes based on the specificcourses that adult students need to complete their degrees, sothere was natural alignment between DWD and ACE.MULTIPLE CONTACT ATTEMPTS AND CONTACTMETHODS ARE NECESSARY TO REACH THESCND POPULATIONShasta reached out to the SCND population threetimes, on each attempt connecting with additionalstudents. For instance, after sending an emailto 542 students, only 38 responded. Shasta thencalled 332 students and received responses froman additional 86 students who either had aninvalid email or did not respond to the first emailcommunication. One additional phone call resultedin another 32 students responding.Figure 2.Response Level Across Contact AttemptsEmail 38First CallSecond Call5048632246232Total That Responded: 156KEYRespondedDid Not RespondShasta’s team also mentioned the possibility of creatingan ACE cohort drawn from its DWD list and establishing arotating schedule of courses to support students reenrollingand completing their degrees. As described by a DWD teammember, near-completers may “only need three or fourclasses but, because of prerequisites or scheduling, if theytook them in a normal semester format, it would take thema couple semesters. But the ACE format allows students topotentially complete everything in one semester.”7AIDING THE COMMUNITY BY SERVING INDIVIDUALS WITH SOME COLLEGE, BUT NO DEGREE SHASTA COLLEGE7

SUSTAINING DEGREE RECLAMATION STRATEGIESThe fourth and final component to Shasta’s engagement withDWD centered on adopting the lessons from its year in theinitiative into the overall practices of the institution. OneShasta official explained that “some of the things that wewere doing for the Degrees When Due population are actuallynow getting adopted by the whole campus. So, having supportfor adult students [who] aren’t familiar with online courses,having a case manager and student facilitator [who’s]following up with students, and having courses in the eightweek accessible format. Those are things that we’re talkingto the rest of the campus about because they could reallybecome best practices.”While the DWD team underscored that its DWD experiencehelped Shasta expand its successes (re)engaging the SCNDpopulation, it also highlighted the beginnings of a broaderreview of practices conducted by the school. “We have agroup now looking at early indicators of people [who] mightstop out with the idea of how do we bring them back. We’realso talking about credit for prior learning and competencybased education,” said one institutional leader. Although DWDwas part of a broader group of initiatives in which Shastawas participating, as this leader explained, “we’ve reached atipping point with the [campus] culture, that I think a lot moreis going to be sustained.”In addition to examining barriers to completion for the SCNDpopulation, Shasta leaders noted other policy changes as theresult of the DWD initiative. “The whole program has reallyhelped us rethink how we are doing things, such as whenpeople claim degrees. The practice previously was studentsapply for their degree if they know they’re supposed to, andthen if students don’t have the requirements for the degree,they receive information saying, ‘sorry, you’re short.’ But nowthese messages explain ‘well, no [you can’t get the degree youapplied for], but you can have this [other] degree.’” In order tomake this policy change, which is more focused on studentcompletion, Shasta needed to make broader changes tograduation requirements and the degree audit process:Ultimately, as one DWD teammember explained, “I think [DWD]changed the whole way awardingdegrees” is happening.Credits: George Milton, PexelsWe moved up when [the registrar] does the degree auditfor students graduating, so that if somebody doesn’t havewhat they need, the registrar can catch it. We changed thepolicy for students identified through DWD from opting-out[of degrees] to opting-in, respecting that some studentsmay have barriers related to immigration status or educationgoals that do not require a degree, but we are making thisprocess much easier for the student.8AIDING THE COMMUNITY BY SERVING INDIVIDUALS WITH SOME COLLEGE, BUT NO DEGREE SHASTA COLLEGE

SUCCESSES AND CHALLENGESAs Shasta leadership and its DWD campus team reflected on their experienceas part of the initiative, a few successes and challenges emerged.SUCCESS #1: IDENTIFYING BARRIERS TO COMPLETION AND REASONSSTOPPED-OUT STUDENTS RETURNShasta College scored its first success early on as officials gained a clearerunderstanding of the barriers that prevent students from completing theirdegree. For example, after completing degree audits for individuals identifiedas part of the SCND population, one of the most common barriers to degreecompletion was a computer literacy requirement. An academic leaderexplained that the faculty “wanted to make sure [students] have computerliteracy and they’re convinced that the only way to do it is through one ofthe options that they’ve proposed, which is primarily to take this computerliteracy class or another class.” This graduation requirement was degreespecific, attached to technical and career-focused programs, but it was theonly missing course for over a third of the SCND population.Although it took several presentations and votes among the members of theacademic senate, the computer literacy requirement was ultimately removedand a similar computer literacy course was added as an option to fulfill ageneral education requirement. A Shasta leader said that a key factor thatconvinced faculty to consider the removal of this graduation requirementwas the DWD data that highlighted this requirement as a significant barrier tothe degree for many students.The DWD initiative also revealed several reasons that students decided toreengage in their postsecondary education. One leader described learningabout these reasons:We thought students would be interested in reenrolling primarily for careerpurposes. Either they want to switch their career or they are getting blockedfrom promotions because they don’t have a degree. While we definitely seethat, just as many students are returning for emotional and personal reasons.Postsecondary education was something that they started when they wereyounger and then life derailed their path, or they started it when they wereyounger and they’ve been in and out of school when they could. I know wehad one guy who’s a financial planner; financially, he was doing just fine, buthe really wanted to complete his associate degree. Another woman, whowas a manager of four chain restaurants in the area, was also doing finefinancially and liked her job but had started her degree years before and waslike, “I just want to finish it.” It’s been hanging over [their] heads for years.NEAR -COMPLETERS WERE WITHINA FEW CLASSES OF DEGREECOMPLETION, BUT MISSING COMMONACADEMIC REQUIREMENTSIn the first degree audit of 324 nearcompleters who had accumulated 60or more credits, students had abouttwo classes remaining to complete adegree.3 The most common classes thatstudents were missing included: thecomputer literacy requirement (65%),general education requirements (51%),major requirements (39%), and math(12%).3. Students in this group had an average of 6.79 creditsremaining to complete a degree. The median was 6, orabout two classes.Figure 3.Missing Academic Requirements65%Computer Literacy RequirementGeneral Education Requirements51%39%Major RequirementsMath12%By better understanding barriers to completion and reasons why formerlystopped-out students were interested in returning, Shasta has been able toimplement policies and practices to remove barriers prior to stop-out andimprove communication strategies to help interested students return.9AIDING THE COMMUNITY BY SERVING INDIVIDUALS WITH SOME COLLEGE, BUT NO DEGREE SHASTA COLLEGE

CHALLENGE #1: ADDRESSING LIMITS TO CAPACITY AND RESOURCESCredits: Peter Griggs, Shasta CollegeA main challenge identified by Shasta’s DWD team is the significantamount of work necessary to start and implement programs focused onsupporting stopped-out students, including project coordination, degreeaudits, academic counseling, and communication. As underscoredby the diverse and cross-functional team recommended by DWD andimplemented by Shasta, many administrative offices are involved in thedevelopment and execution of strategies like adult reengagement andreverse transfer. Given the significant day-to-day work that Shasta’sDWD team members were already responsible for, developing andimplementing new policies and programs is challenging. However, byshifting funding from related projects, Shasta College was able to hire apart-time staff member to serve as the campus lead for DWD and pay forovertime hours for staff members contributing to the DWD project.Shasta’s primary need for staff overtime was the result of inadequatetechnological capacity to automate transcript reviews. During DWD,only two individuals were fully trained on degree audits and they couldcomplete only 25 to 50 transcript evaluations per week. Because thedegree audit process is one of the most time-consuming componentsof the degree reclamation process, a lack of technology and automationrequired Shasta to find alternative ways to complete the work. Throughits work with the DWD initiative and recognition of the importance ofreengaging stopped-out students, Shasta has been actively exploringa technological solution to automate degree audits and expedite theprocess further.SUCCESS #2: ADOPTING DEGREE RECLAMATION AS A PERMANENTINSTITUTIONAL GOALAlthough Shasta College had already acknowledged the importanceof degree reclamation strategies to reach its strategic planning goals,engagement in DWD helped integrate recruiting and supporting stoppedout students into its permanent institutional goals. In part, this decisionis a result of acknowledging the higher-than-average representation ofindividuals with SCND in Shasta’s immediate region and recognizing thekey role Shasta College plays in supporting the community and improvingopportunities for its residents.10IHEP’s Degree Mining Toolis a free online system tohelp institutions efficientlyuse existing technologyand reso

In fact, Shasta College's leadership is so supportive of improving opportunities for the SCND population that it has written degree . its accelerated degree program known as ACE (Accelerated College Education), an adult completion program (see sidebar). ACE and its director, Buffy Tanner, have gained