Transcription

POLICYREPORTACRE 16.02Primary Care and NursePractitioners in ArkansasDavid T. Mitchell, PhDJordan PfaffZachary HelmsPage 0 Volume 1

Primary Care and NursePractitioners in ArkansasExecutive SummaryLike the rest of the country, Arkansas facespolicy brief examines access to primary care ina growing shortage of primary health careArkansas, current restrictions on the use of nurseproviders. One of the most promising approachespractitioners, and the magnitude of diabetes-to alleviating this shortage is to expand the use ofrelated costs in the state that could be alleviatednurse practitioners.by expanding nurse practitioners’ scope ofNurse practitioners aretrained to provide primary care and researchshows to be as effective as physicians inproviding primary care. Although 21 statescurrently allow nurse practitioners full practice toprovide primary care, Arkansas regulationsrestrict nurse practitioner’s ability to practiceindependently diminishing nurse practitioners’ability to meet Arkansans’ primary care needs.Because nurse practitioners are more likely towork in rural areas where primary care needs aremost acute and where primary care has beenshown to stem the rising obesity and ctitioners generates tremendous costs forArkansans’ medical spending and health. ThisPage 1 Volume 1practice.

IntroductionNationwide, policy makers and medicalfewest physicians per resident,5 with considerableprofessionals are concerned by the loomingvariationshortage of primary care physicians.1 ThisArkansas’s counties. Counties with the leastshortage is attributed to many factors, rangingaccess to primary care—such as those along thefrom shifting demographics toward an olderMississippi Delta—often face difficult populationpopulation to fewer medical students choosinghealth issues such as obesity and diabetes thatprimary care, instead favoring more lucrativegreater access to primary care can improve.6specialties.2 Moreover, the demand for tionscare is expected to exceed the available supply byproposed to address the shortage of primarymore than 10 percent in some areas because of thecare providers, the most promising is theincrease in coverage provided through theincreased use of nurse practitioners.7 NurseAffordable Care Act.3 Problems caused by thepractitioners are nurses who have obtained ashortage are exacerbated by the unequalmaster’s degree in nursing science or adistributiondoctorate in nursing practice. These graduateofprimarycarephysicians—especially in poor and rural communities.4Although the shortage of primary caredegrees require both advanced rs is a nationwide concern, Arkansas feelsphysicians, nurse practitioners can pursuethe shortage more acutely than most states do. Inmany specialties in which to practice, but2010, Arkansas ranked second in the nation formany choose primary care.A. Grover and L. M. Niecko-Najjum, “Building aHealth Care Workforce for the Future: More Physicians,Professional Reforms, and Technological Advances,”Health Affairs 32, no. 11 (2013): 1922–27; Association ofAmerican Medical Colleges (AAMC), AAMC PhysicianWorkforce Policy Recommendations (Washington, DC:AAMC, September 2012).2 R. L. Phillips, A. M. Bazemore, and L. E. Peterson,“Effectiveness over Efficiency: Underestimating thePrimary Care Physician Shortage,” Medical Care 52, no. 2:(2014): 97–98; P. Jolly, C. Erikson, and G. Garrison, “U.S.Graduate Medical Education and Physician SpecialtyChoice,” Academic Medicine 88, no. 4 (2013): 468–74.3 E. S. Huang and K. Finegold, “Seven MillionAmericans Live in Areas Where Demand for Primary CareMay Exceed Supply by More Than 10 Percent,” HealthAffairs 32, no. 3 (2013): 614–21.S. M. Patterson et al., “Unequal Distribution of theU.S. Primary Care Workforce,” American Family Physician87, no. 11 (2013).5 Advisory Board, “The 10 States Facing the BiggestPhysician Shortages,” The Daily Briefing, October 22, 2012,accessed May 26, 2016, s.6 A. H. Gaglioti et al., “Access to Primary Care in USCounties Is Associated with Lower Obesity Rates,” Journalof the American Board of Family Medicine 29, no. 2 (2016):182–90; E. R. Lenz et al., “Diabetes Care Processes andOutcomes in Patients Treated by Nurse Practitioners orPhysicians,” Diabetes Educator 28, no. 4 (2002): 590–98.7 J. K. Iglehart, “Expanding the Role of AdvancedNurse Practitioners—Risks and Rewards,” New EnglandJournal of Medicine 368, no. 20: (2013): 1935–41.14Page 2 Volume 1

Currently, 21 states and the District ofAccess to Primary CareColumbia allow nurse practitioners fullTo assess the current status of primarypractice authority to evaluate patients,care in Arkansas, we performed two differentdiagnose conditions, order and interpret tests,analyses. First, we examined county-levelmanage treatments, and prescribe medicine.8data from the Area Health Resources FilesHowever, Arkansas state law and agency(AHRF) produced by the Health Resourcespolices place needless limits on nurseand Services Administration, a division of thepractitioners, especially as it relates to theUS Department of Health and Humanauthority to write prescriptions, the ability toServices. The AHRF compiles aggregate databe reimbursed, by public and private insurers,at the county, state, and national levels fromand to practice without physician supervision.multiple sources such as the AmericanIf Arkansas permitted nurse practitioners toMedical Association, American Hospitalpractice with greater authority, they couldAssociation, and US census into a singleprovide needed primary care to moredatabase to support health care research. WeArkansans.used these data to investigate the availabilityThis policy brief examines thisof primary care physicians at the county level.important issue. First, it describes the currentWe also utilized individual medical claimsstate of access to primary care in Arkansas.data from the Centers for Medicare andThen, it discusses the regulation of nurseMedicaidpractitioners and the barriers they face tounderstand access to care by the elderlypracticing primary care in the state. Finally, itpopulation,explores the incidence of diabetes withinresponsible for much of the recent increase inArkansas as an example of the type andhealth care costs.magnitude of health problems that could beArea Health Resource File ddressed by increasing access to primaryUsing AHRF data, we calculated thecare through expanding nurse practitioners’number of primary care physicians (PCP) perscope of practice.1,000 population in each Arkansas countyfrom 2010 through 2013 (see appendix A). In2013, there were 0.65 PCPs per 1,0008 American Association of Nurse Practitioners, “StatePractice Environment,” accessed May 26, 2016,Page 3 Volume legislation/state-practice-environment.

Arkansans (or 1 PCP per 1,547 people).administrative claims data from the 2013Figure 1 displays the PCP-to-population ratio.CMS 5 percent random sample researchThere is considerable variation by county,identifiable files (RIF), which contain all fee-with more physicians available to serve thefor-service claims associated with a 5 percentpopulation in the urban areas in central,national sample of Medicare beneficiaries.northwest, and northeast Arkansas.WeFigure 1. Number of Primary Care Physicians per1,000 Populationperformed on beneficiaries that resided inidentifiedallphysicianservicesArkansas. We then identified the state inwhich these services were performed andtabulated the number and percentage ofservices performed by providers in Arkansasand in other states. Separately, we identifiedall Medicare services provided by Arkansasphysicians and tabulated the number andpercentage of services performed on patientsin Arkansas and in neighboring states (seetable 1).Source: Area Health Resources Files 2013.Statewide, the ratio of PCPs to population grewby 2 percent per year from 2010 through 2013(see appendix A). However, there wasconsiderable variation between counties, with 22counties experiencing a decrease in PCPs perpopulation over this period. The most severe dropoccurred in rural Newton County, which saw a 50percent decline in the number of PCPs perpopulation.Medicare Claims Analysis:The increased demand for primarycare services is often attributed to a growingelderly population.9 To assess Arkansas’sability to meet the elderly’s medical needswith its primary care workforce, we examined9R. L. Phillips, “Effectiveness over Efficiency.”Page 4 Volume 1

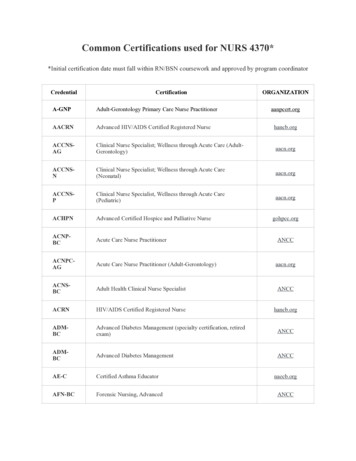

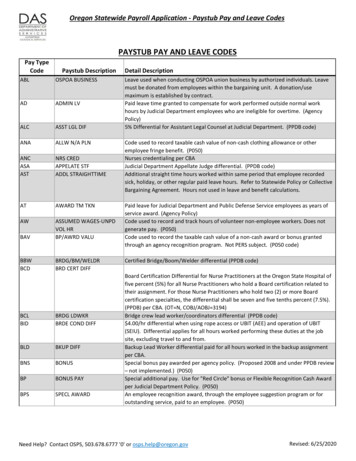

Table 1. State of Service forArkansas Medicare Patients andState of Medicare Patients forArkansas ns constrain their ability to practiceindependently. The FTC pointed out thatArkansas PatientServices by Physician’s State:Total patients and 51,166,456care.Arkansas PhysicianServices by Patient’s State:Total services and 0%1,007,175100%Source: Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2013.As table 1 shows, almost one out of five(19 percent) Arkansas Medicare patientsreceived care outside of Arkansas. It ispossible that these patients simply livednear a state border and traveled to the closestsuitable provider. However, we find that 94percent of Medicare patients who sawArkansas physicians were from withinArkansas. Thus, if Arkansas physicians hadprovided all of their Medicare services in2013 to patients from Arkansas, thenArkansas physicians still would not have met14 percent of the demand for Medicareservices required by elderly Arkansasresidents.10 Unless Arkansas physicians haveextra capacity for additional appointments,they would have to substitute their morelucrative commercially insured patientappointments with Medicare patients to meetthis need. In light of this shortage, it is likelythat a substantial number of elderlyArkansans must to leave the state to seekmedical care.these scope of practice regulations appear tobe based on patient safety, but often extendtowardsprotectionism.Reducingtheregulatory burden and increasing nursepractitioners’scopeofpracticewouldalleviate some problems in Arkansas andwould help attract nurse practitioners toArkansas.Scope of Practice:Scope of practice refers to a medicalprovider’s legal authority to perform specificprocedures, such as referring patients to aspecialist, prescribing medicine, and orderingdiagnostic tests. The American Association ofNurse Practitioners (AANP) groups statesNurse PractitionersA type of Advanced Practice RegisteredNurses (APRN), nurse practitioners providePercentage calculated as follows: 1,166,456 –1,007,175) / 1,166,456.10Page 5 Volume 1into three categories according the scope ofpractice available to nurse practitioners ineach state (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Nurse Practitioner Scope of Practice,2015Full Practice: State practice and licensure lawprovides for all nurse practitioners to evaluatepatients, diagnose, order and interpret diagnostictests, initiate and manage treatments—includingprescribe medications—under the exclusivelicensure authority of the state board of nursing.This is the model recommended by the Institute ofMedicine and National Council of State Boards ofNursing.Reduced Practice: State practice andlicensure law reduces the ability of nursepractitioners to engage in at least one element ofNP practice. State law requires a regulatedcollaborative agreement with an outside healthdiscipline in order for the NP to provide patientcare or limits the setting or scope of one or moreelements of NP practice.Restricted Practice: State practice andlicensure law restricts the ability of a nursepractitioner to engage in at least one element ofNP practice. State requires supervision,delegation, or team-management by an outsidehealth discipline in order for the NP to providepatient care.Source: American Association of Nurse Practitioners, “StatePractice Environment,” accessed May 26, s falls under AANP’s definition of“reducedpractice”fornursepractitioners. Arkansas code does notrecognize nurse practitioners as primarycare providers and they must work undera collaborative practice agreement with aphysician practice. Nurse practitioners arealso limited to prescribing schedule III–Vdrugs while some states allow nursepractitioners to prescribe schedules II–V.this means that patients in Arkansas whosee a nurse practitioner may need aseparate appointment with a physician toget all of their prescriptions. The relevantArkansas codes are as follows:Collaborative Practice: ACA § 17-87102(2) states that a “collaborativepractice agreement” means a written planthat identifies a physician who agrees tocollaborate with an advanced practicenurse in the joint management of thehealth care of the advanced practicenurse’s patients, and outlines proceduresfor consultation with or referral to thecollaborating physician or other healthcare professionals as indicated by apatient’s health care needs.ACA § 17-87-310(c) states:Acollaborativepracticeagreement shall include, but notbelimitedto,provisionsaddressing:(a) The Arkansas State Board ofNursing may grant a certificate ofprescriptive authority to anadvanced practice registerednurse who:Prior to July 2015:Page 6 Volume 1

2) Has a collaborative practiceagreement with a practicingphysician who is licensedunder the Arkansas MedicalPractices Act, §§ 17-95-201 –17-95-207, 17-95-301 – 1795-305, and 17-95-401 – 1795-411, and who has trainingin scope, specialty, orexpertise to that of theadvanced practice registerednurse on file with the Board.1. ltation or referral, or both;2. Methods of management of thecollaborative practice, which shallinclude protocols for prescriptiveauthority;3. Coverage of the health care needsof a patient in the emergencyabsence of the advanced practicenurse or physician; and4. Quality assurance.Prescriptive Authority: ACA § 17-87310(a)(2) provides that:An advanced practice nurse mayobtain a certificate of prescriptiveauthority from the Arkansas StateBoard of Nursing if the advancedpractice nurse has a collaborativepractice agreement with a physicianwho is licensed under the ArkansasMedical Practices Act, and who has apractice comparable in scope,specialty, or expertise to that of theadvanced practice nurse on file withthe Arkansas State Board of Nursing.11The FDA rescheduled hydrocodone combinationsfrom schedule II to schedule III in 2014. In Arkansas, nursepractitioners may prescribe schedule II hydrocodonePage 7 Volume 1(a) The Arkansas State Board ofNursing may grant a certificate ofprescriptive authority to anadvanced practice registerednurse who:(1) Submits proof of successfulcompletion of a board-approvedadvanced pharmacology coursethat shall include preceptorialexperience in the prescription ofdrugs, medicines, and therapeuticdevices; and(2) Has a collaborative practiceagreement with a physician whois licensed under the ArkansasMedical Practices Act, § 17-95201 et seq., § 17-95-301 et seq.,and § 17-95-401 et seq., and whohas a practice comparable inscope, specialty, or expertise tothat of the advanced practiceregistered nurse on file with theArkansas State Board of Nursing.(b) (1) An advanced practiceregistered nurse with a certificateof prescriptive authority mayreceive and prescribe drugs,medicines, or therapeutic devicesappropriate to the advancedpractice registered nurse’s area ofpractice in accordance with rulesestablished by the Arkansas StateBoard of Nursing.(2) An advanced practiceregistered nurse’s prescriptiveauthority shall only extend todrugs listed in Schedules III–V.11(c) A collaborative practiceagreement shall include, but notcombinations if the collaborative practice agreement withthe physician expressly allows it.

belimitedto,provisionsaddressing:(1) The availability of thecollaboratingphysicianforconsultation or referral, or both;(2) Methods of management ofthe collaborative practice, whichshall include protocols forprescriptive authority;(3) Coverage of the health careneeds of a patient in theemergency absence of theadvanced practice registerednurse or physician; and(4) Quality assurance.provide comparable quality to physicians forprimary care patients,13 culminating with a2011InstituterecommendingThe regulation of nurse practitioners isMedicinereportthatadvancednursepractitioners be free to practice to the fullextent of their training. Based on this researchand the experience of nurse practitioners instates that allow full practice, the NationalGovernors Association has recommendedthat states provide full practice to nursepractitioners to help alleviate the growingprimary care ationsareoftensafeguardthepublic,driven by stated concerns for patient safety,sometimes regulations do more harm thanwith the American Medical Associationgood. Excessive regulation may not generatestrongly supporting scope of practice lawsmeaningfulthatfrombarriers that curb competition. In the case ofproviding primary care without physiciannurse practitioners, these barriers restrict theoversight.12 However, a considerable body ofservicesresearch indicates that nurse rierscreatemayseveralproblems:12Iglehart, “Expanding the Role of Advanced NursePractitioners.”13 M. Swann et al., “Quality of Primary Care byAdvanced Practice Nurses: A Systemic Review,”International Journal for Quality in Health Care 27, no. 5(2015): 396–404.; R. P. Newhouse et al., “AdvancedPractice Nurse Outcomes 1990–2008: A SystematicReview,” Nursing Economics 29, no. 5 (2011): 230–50; M.Laurant et al., “Substitution of Doctors by Nurses inPrimary Care,” Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews2:CD001271, 2005; D. W. Roblin et al., “Use of MidlevelPractitioners to Achieve Labor Cost Savings in the PrimaryCare Practice of an MCO,” Health Services Research 39,no. 3 (2004): 607–26; E. R. Lenz et al., “Primary CareOutcomes in Patients Treated by Nurse Practitioners orPhysicians: Two-Year Follow-Up,” Medical Care Researchand Review 61, no. 3 (2004): 332–51; M. O. Mundinger etal., “Primary Care Outcomes in Patients Treated by NursePractitioners or Physicians: A Randomized Trial,” Journalof the American Medical Association 283, no. 1 (2000): 59–68; P. Venning et al., “Randomised Controlled TrialComparing Cost Effectiveness of General Practitioners andNurse Practitioners in Primary Care,” BMJ: British MedicalJournal 320, no. 7241 (2000): 1048–53.14 National Governors Association, “The Role ofNurse Practitioners in Meeting Increasing Demand forPrimary Care,” December 20, 2012, accessed May 26,2016, ractitioners.html.15 M. M. Kleiner et al., “Relaxing OccupationalLicensing Requirements: Analyzing Wages and Prices for aMedical Service”Page 8 Volume 1

difficultyschedulingappointments for primary carelonger in-office waiting times NursePractitioners’ Scope of Practicenurse practitioners’ scope of practice is that itcare costsdirectly increases the number of providershigher administrative costs foravailable for primary care services. However,physicianthere are many other advantages, too:practicesthatMore generally, reduced competitiontoExpandinghigher patient and payer healthemploy nurse practitionersleadsofThe primary argument for expandingto see a provider necessary to protect consumers.16Advantagesand routine visits these regulations frequently exceed what islessinnovationandgreaterconsolidation, which increase costs andImproved Access in UnderservedAreas: Nurse practitioners are much morelikely to practice in rural and underservedareas than physicians are.17Innovation: The increased use of nursereduce access to care.Thus, even well-meaning regulationspractitioners is likely to spur innovation inmay not be effective when considering theirhealth care delivery. For example, advancedoverall effect. The trick is to balancepractice nurse-staffed clinics generally offerprotection with competition, which oftenweekend and evening hours, unlike moststarts with a focus on the overall outcomes ofprimary care physicians. This schedule nota regulation rather than the inputs. In light ofonly provides greater flexibility for patients,theseTradebut also provides competitive incentives forCommission examined state regulations ofother types of clinics to offer extended hoursadvanced practice nurses and concluded thatas well.18concerns,theFederal(working paper w19906, National Bureau of EconomicResearch, 2014); P. Pittman and B. Williams, “PhysicianWages in States with Expanded APRN Scope of Practice,”Nursing Research and Practice (2012); J. A. Fairman et al.,“Broadening the Scope of Nursing Practice,” New EnglandJournal of Medicine 364, no. 3 (2011): 193–96.16 M. M. Kleiner et al., “Relaxing OccupationalLicensing Requirements”; Pittman and Williams,“Physician Wages”; Fairman et al., “Broadening the Scopeof Nursing Practice.”17 Federal Trade Commission (FTC), PolicyPerspectives: Competition and the Regulation of AdvancedPractice Nurses (Washington, DC: FTC, 2014); K.Page 9 Volume 1Grumbach et al., “Who Is Caring for the Underserved? AComparison of Primary Care Physicians and NonphysicianClinicians in California and Washington,” Annals of FamilyMedicine 1, no. 2 (2013): 97–104; K. Martin, “NursePractitioners: A Comparison of Rural-Urban PracticePatterns and Willingness to Serve in Underserved Areas,”Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 17(2000): 337–41.18 Massachusetts Department of Public Health,“Commonwealth to Propose Regulations for LimitedService Clinics: Rules May Promote Convenience, GreaterAccess to Care,” press release, July 17, 2007.

Greater Physician Focus: Althoughstates—all of which have similar or morenurse practitioners receive excellent trainingrestrictive regulations for nurse practitioners’for primary care, they are not replacementsscope of practice (see figure 2). If Arkansasfor physicians. According to the Institute ofallowedMedicine,19 the expansion of nursing scopesopportunities should lure advanced practiceof practice has not diminished the critical rolenurses from neighboring states. Arkansas’sof physicians in patient care nor has it reducedrelatively low cost of living may entice nursephysician incomes. Rather, greater use ofpractitioners currently enjoying full practicenurse practitioners allows primary careelsewhere.physicians to focus on higher-cost and moreopportunitiescomplex services, which may lead to lowerregistered nurses in Arkansas to pursueoverall costs and higher-quality care.20advanced training given an average ntivizecurrentdifferential of 37,000.22 Using AHRF data,we estimate that the number of nurseGiven that 21 other states currently allowpractitioners has grown by 10 percent per yearfull practice for nurse practitioners, willfrom 2010 through 2013 (appendix B),Arkansas be able to attract sufficient numbersindicating that Arkansas is competitive in thisto alleviate the primary care shortage ifmarket.23regulatorsexpandnursing’sscopeofTo investigate the effect of expandingpractice? A cursory examination indicatesadvanced practice nurses’ scope of practicethat this outcome is likely. Althoughon Arkansas’s ability to attract more nurseArkansas’snursepractitioners, we estimated a multivariatepractitioners ( 93,870) is lower than theregression model using all 50 states. Wenationalaverageaveragesalaryfor( 101,260),21itisscored each state based on the ability of nursecomparable to that of Arkansas’s neighboringpractitioners19 Institute of Medicine, The Future of Nursing:Leading Change, Advancing Health (Washington, DC:National Academies Press, 2011).20 M. H. Katz, “The Right Care by the RightClinician,” JAMA Internal Medicine 175, no. 1 (2015): 108;D. R. Hughes, M. Jiang, and R. Duszak, “A Comparison ofDiagnostic Imaging Ordering Patterns between AdvancedPractice Clinicians and Primary Care Physicians FollowingOffice-Based Evaluation and Management Visits,” JAMAInternal Medicine 175, no. 1 (2015): 101–7.21 US Department of Labor, Bureau of LaborStatistics, “Occupational Employment and Wages, May2014, 29-1171 Nurse Practitioners,” accessed May 24,2015, http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291171.htm.22US Department of Labor, Bureau of LaborStatistics, “Occupational Employment and Wages, May2014, 29-1171 Nurse Practitioners,” accessed May 24,2015, http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291171.htm23 Many of Arkansas’s nearby neighbors haveproposed legislation allowing full practice authority fornurse practitioners.to(1)referpatientsPage 10to Volume 1

specialists, (2) work without a collaborativeArkansas has high incidence of diabetespractice agreement, (3) work without anywhichother specific physician involvement, and (4)geographically. Uncontrolled diabetes isprescribe schedule II–V drugs. We scoredexpensive for payers and patients. Diabeticeach state from one to four using equalpatients need primary care.weighting.24 Higher scores imply Usingpatients, including those with complicationsordinary least squares (OLS), we accountedand comorbidities, have excellent outcomesfor per capita real gross state product, thewhen cared for by nurse practitioners.percent of the population with income belowIncidence of Diabetes in Arkansasthe poverty level, and the percent of theAccording to the Centers for Disease Controlpopulation living in rural areas. We found thatand Prevention (CDC), 9.3 percent of the USincreasing a state’s score by one pointpopulation has diabetes, costing society 176(improving any one of the scope of practicebillion annually in medical spending andrules) would lead to 1.23 additional nurseanother 69 billion in indirect costs frompractitioners per state. Thus, expanding thedisability, missed work, and prematurescope of practice would increase the numberdeath.27 Arkansas is no different from theof nurse practitioners in Arkansas by 3.69 pernation as a whole. Using data from the CDC’sisunequallydistributed25-26.Diabetic2010 Behavioral Risk Factor SurveillanceDiabetes: A PrimaryCare Problem100,000.OLS ModelNPs per 100k pop 0 1 Score 2%Rural 3%Poverty 4 per capita realGDP 24 Results were robust to scoring measures that didnot weight each value equally.25 Saaristo, T., Moilanen, L., Korpi-Hyövälti, E.,Vanhala, M., Saltevo, J., Niskanen, L., . & Uusitupa, M.(2010). Lifestyle intervention for prevention of type 2diabetes in primary health care one-year follow-up of theFinnish National Diabetes Prevention Program (FIN-D2D).Diabetes care, 33(10), 2146-2151.Page 11 Volume 1System, we calculated the incidence ofdiabetes at the state and county levels usingthe responses to the question, “Have you everbeen told by a doctor that you have lation has been diagnosed with diabetes.However, there is considerable variation atthe county level (see figure 3).26 Whittemore, R., Melkus, G., Wagner, J., Northrup,V., Dziura, J., & Grey, M. (2009). Translating the diabetesprevention program to primary care: a pilot study. Nursingresearch, 58(1), 2.27 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetesand Its Burden in the United States (Atlanta: USDepartment of Health and Human Services, 2014).

Table 2. UncontrolledHospitalizations in ArkansasThe highest incidence of diabetes occurs inthe state’s southeast region (Desha County,17.9 percent; Phillips County, 17.2 percent)Yearand northeast corner (Clay County, Ratepercent). The northwest and northeast havethe lowest incidence. Miller County has thelowest incidence of diagnosed diabetes at 4.6percent.Figure 3. Arkansas Incidence of Diabetes, 166,0116,1045.1DiabetesAggregateCosts ( 645,056,09143,331,64044,836,95224.90.73.2Source: Analysis of US Dept. of Health andHuman Services Area Health Resources Files and CMS5 percent Medicare Claims Files.Simply curbing the annual growth rate of 3.2 percentper year in aggregate costs from uncontrolled diabeteshospitalizations would eliminate 195 hospitalizations.Reducing uncontrolled diabetes hospitalizations by 25percent would save taxpayers 11 million per year.Diabetes and Nurse Practitioners:ExtensiveSource: CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.evidenceshowsthatTable 2 presents costs associated with hospitalizationsprimary care interventions have substantialfrom uncontrolled diabetes in Arkansas from theeffects on the risk factors, incidence, lthcare Cost and Utilization Project. In 2013,ofdiabetes.Thus,anythingalleviating the primary care shortage coulddiabetes hospitalizations in Arkansas cost 44.8million. This figure doesn’t include the annual cost ofhave dramatic effects in diabetes care andtreatment for the 200,000-plus diabetes patients whooutcomes. However, the gains appear to bewere not hospitalized.magnified when primary care diabetesinterventions are managed by advancedpractice nurses. There is no consensus behindwhy this occurs, though possible explanationsare that advanced nurse practitionersPage 12 Volume 1

spend an average of 12Decreas

nurse practitioners. Nurse practitioners are trained to provide primary care and research shows to be as effective as physicians in providing primary care. Although 21 states currently allow nurse practitioners full practice to provide primary care, Arkansas regulations restrict nurse practitioner's ability to practice