Transcription

ReachingTippingPoint?Climate Changeand Poverty inTajikistan

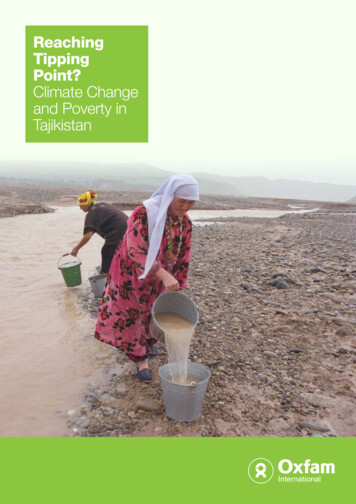

ContentsSummarySummary2Climate Change: Past, Present and Future5Climate Change: Poverty and Low adaptive Capacity9Climate Change: Agriculture and Food Security11Climate Change and Water14Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction17Challenges of Adapting to Climate Change19Conclusions21The people of Tajikistan, a small, mountainouscountry in Central Asia, are experiencing theimpacts of climate change. More frequentdroughts and heightened extreme weatherconditions are hitting poor communities,eroding their resilience. The country’s glaciersare melting, bringing the danger, in the future,of greater water shortages and even disputes inthe wider region. Last summer’s unusually goodrains and consequent harvest brought somerelief to rural communities across Tajikistan butthe long-term trends are clear – and ominous.investments that are beyond the financing capacitiesof most governments acting alone.“It’s not crisis point yet butit will be soon”Timur Idrisov, NGO, Little Earth,October 2009.This Oxfam report is based on interviews undertaken incommunities in Spitamen and Ganchi in the north andVose, Fakhor and Temurmalik in the south in October2009. It gives an insight into how poor men and womenare experiencing climate change, what challenges theyare currently facing – and will continue to face in thefuture. It makes suggestions for what they say needs tohappen to help them cope better with climate change.This report draws attention to the plight of poorcommunities in Tajikistan, and also highlightsOxfam’s demands for a climate change deal that isboth fair and safe – that agrees both the drastic cutsthat are necessary in greenhouse gas emissions andthe new funds that developing countries like Tajikistanneed to adapt. Oxfam considers the United Nationsconference on climate change at Copenhagen a hugedisappointment, and the Accord that came out of it,a “climate shame”. The talks were characterized bychaos and near-collapse. The pursuit of national interestby the major powers deepened the mistrust betweendeveloped, developing and industrializing countries.2010 may be the last chance for these climatenegotiations to prove they are an effective process forstopping climate change by delivering a fair, ambitiousand binding deal. The time for action is now.“Last year was drought – for 3 yearswe could not grow wheat and barley.Because of 3 years of drought we arenot planting wheat in rain-fed lands,people do not want to invest,” SaidshoevAbdualim, a village elder in Vose District,October 2009. Photo: Anita SwarupTajikistan’s plight highlights the international injustice ofclimate change. Tajikistan is one of the countries leastresponsible for the greenhouse gas emissions that arecausing climate change. It ranks around 109th in theworld for all greenhouse gas emissions and 129th inemissions per capita; its people emit less than 1 tonneof carbon dioxide per head, compared to nearly 20tons by citizens of North America.1The government of Tajikistan recognises the factand importance of climate change and its impacts,but it faces serious challenges in terms of fundingand lack of capacity to cope with such a potentiallyoverwhelming phenomenon. Increased funding forresearch on the impacts of climate change is urgentlyneeded. Planning in high-risk environments requires1Temurmalik District, south Tajikstan. Photo: Anita Swarup2

passive solar greenhouses to grow vegetables offseason - particularly in the winter when the ground isfrozen. This helps improve food security and providesextra nutrition for families. Researchprograms on climate change, its impactson natural resources, the economy and public health,development and adaptation measures.Planning needs to take into consideration livelihoodresilience strategies, socially disaggregatedvulnerability assessments, gender-disaggregateddata and capacities for disaster risk management –all at the local level. Scaling up community-ownedapproaches where people come together for trainingand awareness raising will be central to successfulnational strategies. Women who carry much of theburden of farm and household work, must be at thecentre of adaptation strategies, and for this, genderdisaggregated data and research is necessary. Understand,respect, evaluate and build upon localknowledge. In adapting to climate change, manyfarmers are already using local remedies for theincreasing level of pests, for example using garlicaround fruit trees to ward off locusts and other insects. Buildinstitutional and technical capacity onadaptation. Adaptation will require skilled personnel inall fields, including climate and hydrological research,geographical information systems, environmentalimpact assessment, protection and rehabilitationof degraded land, water use, conservation ofecosystems, agricultural and infrastructuredevelopment and health protection.Recommendations: National SupportRecommendations: Regional and International†farmers to adapt agriculture to ensureproduction under changing conditions. Strategiesshould include crop diversification, developmentand introduction of drought-resistant crops andseeds and improvements in livestock breeding.Climate change threatens food security through bothseasonal changes and pressure on water availability.“The drought is becoming more severeand the temperature is increasing. Lastyear there was drought. The wheat plantscannot grow as the high temperaturesaffect them. We can’t harvest fodder forthe animals. We need livestock to sell forvegetables and to buy water”Shovaliev Nurali, a farmer inHansanbek village, Temurmalik District,October 2009. Photo: Anita Swarup Ata time when the urgency of the climate changechallenge is becoming blatantly clear, standoffs between the most powerful countries at theCopenhagen Conference have left the world headingtowards 40C global warming – a catastrophicprospect. Negotiations must get straight back ontrack to keep global warming far below 20C andpoliticians, negotiators, scientists and the public mustcommit to sustained and focused engagement thatdelivers a fair, ambitious and binding deal in 2010. Mountpublic awareness campaigns on climatechange in communities, schools and media, andcampaigns at local level to raise people’s awarenessin communities, through a concerted joint effort bygovernment and civil society (non-governmental)organizations in Tajikistan. TheCopenhagen Accord commits developedcountries to providing new and additional “fast-start”finance for adaptation and mitigation approaching 30 billion for the period 2010-2012. This is welcome– but must be additional to existing aid pledges.Further commitments are required to meet theestimated shortfall of 2 billion per year with clearcommitments on funds needed from 2014 to 2019. Centreresearch and policy planning on adaptationon the needs of poor people and their key areas ofconcern. The social and economic impact of climatechange on poor people should be at the forefront ofresearch and policy formulation.Recommendations: Community Level: Improveaccess to water. Local communitiesconsider water the key priority, both for agricultureand domestic use. Climate change – notably risingtemperatures and more droughts – is putting anadditional stress on water resources. Farmerswant improved water management, water storagereservoirs, water saving techniques such as dripirrigation, and more access to safe water fromboreholes.Collecting water from a tapstand by the side of the road. Thisis a job for women. Photo: Karen Robinson/Oxfam Integrateclimate planning across governmentdepartments. Climate change concerns should notbe under a particular sector – and particularly notseen as only an environmental issue - but integratedacross all sectors including agriculture, trade,transport and energy. TheAccord also calls for 100 billion to be mobilizedfor adaptation and mitigation by 2020, which iswelcome but only half the minimum sum needed.Furthermore it does not say how it will mobilizedor by whom. Rich countries must clearly state thatdevelopment aid will not be pillaged to pay forclimate change. Finance must be raised separatelyand be additional to aid commitments of 0.7 per centof national income. Integrateclimate change adaptation into nationalplanning and budgets, particularly for sustainabledevelopment and poverty alleviation. Improvemethods of food storage and preservation.Farmers say they want to plan for future hard timesand store more food. Providemore support and training in agriculturaltechniques, marketing and setting up agriculturalshops in which to buy and sell agricultural produceand seeds. Scale se climate change as an opportunity to scale upUdisaster risk reduction programmes. Strengthen theCommittee for Emergency Situations, for example onEarly Warning Systems, and the State Organisationfor Hydrometeorology on monitoring glaciers,snowmelt and flood hazards. InCentral Asia, institutions for regional co-operationmust be strengthened, in particular to monitor andmanage water resources in the light of glacial melt,higher temperatures and increases in water scarcity.For further details of Oxfam International’s analysisand recommendations for action following theCopenhagen climate talks see the Oxfam BriefingNote: Climate Shame: get back to the �� up better insulation of houses. Expand use ofenergy efficient stoves to increase people’s accessto energy for cooking and heating and to improvewomen’s health as well as reducing use of biomassfor fuel. Boost biogas and solar power, and smallhydro in mountain communities. Expand use of PromoteShibanai village - washing hanging out to dry. The village’sonly water source is the river so getting water for drinking andwashing is always a problem. Photo: Anita Swarup3disaster risk reduction at local levels bysupporting community-based strategies. This methodis more effective and has benefits that go beyond justtackling climate-driven disasters. Ensure women are atthe centre of community-level responses.4

Climate Change: Past, Present and Future“The effects of climate change are already visiblein higher average air and ocean temperatures,widespread melting of snow and ice, andrising sea levels Globally, precipitation hasincreased even as Australia, Central Asia, theMediterranean basin, the Sahel, the westernUnited States, and many other regions have seenmore frequent and more intense droughts.”3currently in the atmosphere come from emissionsfrom the US, Europe, Australia and Japan.“We are seeing more extremeweather conditions andmore extreme cold and moreextreme heat, particularlyin the valley . If nothing isdone, all the glaciers willmelt and I don’t know if wewill have water in 20 years”Natalya Mirzokhonova,IMAC (Information Managementand Analytical Centre)Global and regional climate patterns have changedthroughout the history of our planet.Prior to the Industrial Revolution these changesoccurred due to natural causes but since the late1800s, scientists believe the changes have beenincreasingly influenced by rising atmosphericconcentrations of carbon dioxide and othergreenhouse gases (GHGs) as a result of humanactivities, such as fossil-fuel combustion and landuse change. Most of the excess greenhouse gasesThe greatest concern in Tajikistan has been anincrease in air temperature, which has seriousAnnual airtemperatureanomalies in TajikistanChange in air temperaturefor the period 1940-2000In 2007 the Youth Ecological Centre, Dushanbe,conducted a number of surveys on people’sperceptions of climate change in Khatlon, Soghd andPamir. People interviewed particularly rememberedthe unusual, intense heat of the summer of 2005,accompanied by insufficient irrigation water anddifficulties with grazing. In Khatlon many peoplesuffered that year from high blood pressure andheart disease. At the same time, villagers elsewherereported unusually cold winters in 2005/6 and2007/8 with abnormally heavy snowfalls andsnowstorms.8implications for its glaciers and water resources.Ground air temperatures are increasing in mostdistricts and high altitude zones.4 The biggestincrease of annual mean temperature has beenat Dangara at 1.2 degree C and Dushanbe at 1.0degree C over a 65-year period. In mountainousareas, 1.0-1.2 degree C was observed in Khovaling,Faizabad and Iskashim. There has also beenan increase of the number of days maximumtemperatures have reached 40 degrees C or over.There has been an increase in east and south - east(warm) winds, and a decrease in west and south west (cold) winds. Thunderstorms and hailstorms,both associated with cold fronts, have decreased.Droughts will likely be more intense and frequent inthe future. One of the worst droughts was in 2000-1where, in the lowland arid region of the Amu DaryaRiver Basin (e.g. Karakalpakstan), access to waterwas halved.5 Climate change will worsen a long-termspiral of intensifying aridity in Central Asia includingTajikistan.6“In the last 10 years, thenatural cycles are changing.In comparison, dry spells arebecoming longer. Last year in2008 was the longest periodof drought”Pulotjon Usmonov, an agronomistfrom the NGO, Saodat.According to the IPCC (2007) “the projecteddecrease in mean precipitation in Central Asia will beaccompanied by an increase in the frequency of verydry spring, summer and autumn seasons. Changesin seasonality and amount of water flows from riversystems are likely to occur due to climate change.Changes in runoff of river basins could have asignificant effect on the power output of hydropowergenerating countries like Tajikistan, which is the thirdhighest producer in the world.” 7In 2008 Tajikistan suffered one of the worst droughtsit has ever experienced. According to the UNHumanitarian Food Security Appeal, 2008, “fromApril onwards, temperatures across the country havebeen significantly higher than normal. In southernTajikistan particularly, temperatures deviated morethan 5 degree C from the norm. Precipitation hasbeen significantly lower than normal and in somecases as much as 43 percent below average.”9Extreme weather events and their variabilitySource: State Administration for hydrometeorologyDushanbeShaartuz, south TajikistanDays with extremely high temperatureSemi-days with heavy rainIncrease in mean annual air temperatures over the 50 years. Source: Tajikistan Second National Communication under UNFCCC (2008).56

stressed. According to a recent report by the WorldBank, ‘Adapting to Climate Change in Europeand Central Asia’, “the consequences of climatechange would overstretch many countries’ adaptivecapacity, contribute to political destabilization andtrigger migration. As warming progresses, it is likelyto intensify national and international conflicts overscarce resources.” 12Change in surface area of Central Asian glaciersin the last half of the 20th centurymelted area as % of the initial glacier areaTien ShanGissar AlaiThe Pamirs andFedchenko glacierLuigi de Martino, Centre for Education and Researchin Humanitarian Action, University of Geneva, whohas studied this issue, notes, “The downstreamregions of the Amu Darya are [political] hotspots andmore areas will become like this – with water quantitydecreasing and environmental degradation – andadd to that climate change which is an exacerbatingfactor.”13NorthernAfghanistanSource: State Administration for hydrometeorologyChange Specialist, Tajikistan Organisation forHydrometeorology. The State Organisation forHydrometeorology lacks the resources and capacityfor the overwhelming task of monitoring all glacialactivity in Tajikistan.“The main problem of melting glaciers is floatingbroken ice and debris which can block riversand form glacial lakes and reservoirs and this ishappening now. We need resources to monitorglaciers as some are potentially very dangerous.There are hundreds of glaciers but we only knowa few percent” said Nailya Mustaeva, ClimateThe IPCC (2007) reports temperature rise in CentralAsia will also lead to a higher probability of potentialdisasters such as mudflows and avalanches.Projected degredation of glaciers by 2050’sYuri Skochilov, Youth Ecological Centre reportsthat “cycles of droughts have become shorter andtemperatures in the southern part of Tajikistan havegone up by around 5 degrees C. Every year it getsworse.”10-20 percent of water into rivers but during dry andhot years it can be up to 70 percent.10 Tajikistan hasaround 8492 glaciers and its glaciers regulate riverflow and provide water not only for Tajikistan but alsofor neighbouring Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.Extreme weather conditions are also affecting thecountry. In 2008 winter temperatures fell to aroundminus 20 degrees C for more than a month.“It was the first time that there was this kind of coldweather in 2008 – around minus 20. Before, therewas not this kind of weather. This is climate change.The cold winter affected the plants which are mostlysub-tropical in this region – figs, pomegranates andgrapes were frozen,” reports Boboev Tillo, Director ofBotanical Garden, Kulyab.Its largest glacier, Fedchenko Glacier in the PamirMountains, is around 70 km long but this is meltingat a rate of 16-20 metres a year. According to theSecond National Communication, observations showthat the glacier reduced by around 44 sq km or by6 percent from 1966-2000. Glaciers in the Murghabriver basin have become depleted by around 30-40percent in the last few decades. Other glaciers havecompletely disappeared, including five small glaciersaround Lake Sarez. This is likely to have contributed tothe steady trend of rising water levels in the lake.There is a real concern about Tajikistan’s glaciers.According to Ilhomjon Rajabov, Head of ClimateChange and Ozone Centre, Tajikistan StateOrganisation of Hydometeology, around 20 percenthave retreated and some have already disappeared.Up to 30 percent more are likely to retreat ordisappear by 2050. Annually, melting glaciers bring inThe Amu Darya River in Tajikistan is one of the mainsuppliers of water for the Aral Sea and to Uzbekistanand Turkmenistan as well as Tajikistan. Accordingto some model predictions, the availability of waterin this river may decrease by up to 40 per cent.11That could exacerbate already strained relationsbetween the countries in a region that is water-7Terminus moraineof theFedchenko GlacierRetreat of the Fedchenko Glacier terminus. Photo: V. Novikov8

Climate Change, Poverty andLow Adaptive CapacityA low-income country, around 53 percent ofTajikistan’s population of seven million peoplelive on less than USD 1.33 per day.14 And,although less than seven percent of its landis arable, around two thirds of the populationdepend on agriculture for a livelihood – cotton,wheat, nuts, fruit and vegetables.“Last year we had to sell our livestock in order tobuy wheat flour – and more people went to Russiaor Dushanbe to work. In future if these conditionscontinue, we will have to move” notes Shovaliev Nurali,a farmer in Hansanbek village in Temurmalik districtPeople in Tajikistan are resilient when faced withdifficulties and adept at taking advantage of goodweather, as the 2009-cropping season showed. Timelyand well-distributed rainfall, improved seeds, and wideruse of fertilizer all contributed to this improvement,according to the FAO. But challenges posed by climatechange already strain their capacity to cope and mayoverwhelm it if temperatures continue to rise. Tajikistan,according to a recent World Bank report,15 is the mostvulnerable country in the region to climate change andhas the least capacity to adapt. Adaptive capacity is theability of a system to adjust to climate change, includingclimate variability and extremes, in order to moderatepotential damages, to take advantage of opportunities,or to cope with the consequences.16Girl in cotton field, south Tajikstan. Photo: Anita Swarupassets (crops, orchards and livestock), the agingenergy infrastructure collapsed under the demandfor electrical power to heat urban centres and thecold damaged rural and urban water supply systemsdue to frozen pipes and other structural problems exacerbating lack of access to safe drinking water.There was a 40 percent decline in agricultural yieldsfollowing the harsh winter and drought.19“The main thing for us is theland, we take all the incomeand food from the land. Wedon’t have factories to goto work. That is why we askGod for good weather,”Soqimatov Tohijon, Assistant toChief in Togoyak local government,Spitamen, north TajikistanAlmost two thirds of agricultural production isirrigated17 but many farmers still have to makea precarious living from rain-fed land – which isconsiderably more vulnerable to the impacts ofdrought and climate change. The FAO says: “Theimportance of irrigation from the glacier sourcesnotwithstanding, some 55% of the area sown towinter cereals depends on precipitation duringthe cropping season”. Before the good rainsand excellent harvest in 2009, several dry years(2000/2001, 2005/6/7} posed challenges to foodsecurity. Droughts in 2000 and 2001 cost Tajikistan 5percent of its GDP.18 Continued drought in the springand summer of 2007, as well as a locust invasionfurther stretched the capacities of households tosuccessfully cope. Against the backdrop of increasedfood insecurity, in early 2008 Tajikistan experiencedthe worst winter in decades with temperaturesfalling to minus 20 degrees C. The exceptionallycold weather damaged or destroyed agriculturalIt cost the economy around US 850 millionand around 2.2 million citizens experienced foodinsecurity with 800,000 of these in need of immediateassistance.20 Many winter crops were destroyed, 70percent of the livestock died, 90 percent of industrystood idle and while electricity was supplied in thecapital for 4 hours a day, rural areas were withoutelectricity for weeks. A drought and record hightemperatures in summer of 2008 followed the coldwinter. Tajikistan is vulnerable to a ‘compound crisis’phenomenon such as that which threatened water,energy and food security in the early months of 2008.219burdens will be placed on women as many have towork in the cotton fields as well as collect water andfirewood, grow food and manage the household.More women work in the lowest paid sectors such asagriculture. With the closure of state-run kindergartensand the increasing reliance on the consumption ofhome produced foodstuffs, the burden of unpaid workin the home has increased rather than diminished as aresult of this transition.24Floods, mudflows and avalanches may increasewith climate change (for example sudden and rapidglacial melts) as they already occur regularly aroundthe spring melt. There was a particularly severe andunprecedented flood in Hamadoni district in Khatlonin 2005 caused by heavy winter snowfall followed byvery warm weather in June and July, causing excessivesnowmelt. Over 11,000 people were evacuated. Lackof maintenance of flood defences and canals were alsoculpable. Climate shocks compound cycles of poverty.When drought, floods or extreme weather conditionsdestroy crops and livelihoods, communities are thrownfurther into poverty – as a result, many move away toseek work. Migration to Russia is key to Tajikistan’seconomy and remittances constitute the mostimportant income for many households in Tajikistan.These transfers total about US 400 million to US 1bn or from 20 percent to 50 percent of its GDP.22 In2006, almost 1m workers, mostly men and boys, wentto work in Russia.23 As populations on the margin seekwork or are forced from their homes by extreme events,the pressure to migrate to Russia is likely to increase.Tajikistan, like other countries in Central Asia, alreadysuffers from serious challenges to the health of itsenvironment. Soil fertility management and nutrientconservation are poor, pesticide and fertilizer usepollutes many waterways. . Floods are beingexacerbated by rampant deforestation. The nation’sforest reserves have dwindled from 1.3 metres cubedper person in 1990 to 0.9 metres cubed per personin 2003. Deforestation has been put down to cuttingtrees, stock grazing and an increase in the number ofinsect pests. The increase in pests is associated withincreased temperatures. Acceleration in deforestationwas linked to the severe winter of 2007/2008 andshortages of electricity, gas and other energy supplies,forcing people to cut trees in the mountain forests.25As a result of male migration, there are a significantproportion of female-headed households. IncreasingAdaptive capacity toclimate change.2520Source: Fay and Patel(2008)Taken from WorldBank, June 2009,Adapting to ClimateChange in Europe andCentral AsiaVulnerability toclimate change151050ia lic ry ia ia ia ia d ia ia ia y ia ia ia ia n e R ia s ia a n lic n n nen b ga on ak at an lan tv an ar rke rb an sn ss sta ain FY en aru rg ov aija b sta sta staov epu un Est Slov Cro ithu Po La om Bulg Tu Se Alb Bo Ru akh Ukr ia, Arm Bel Geo old erb epu eki ajik enilS R HM Az R zb T kmRLzonryz UKachedTurgreacKyCzM2520Source: Fay and Patel(2008)Taken from WorldBank, June 2009,Adapting to ClimateChange in Europe andCentral Asia151050a a aa s e aa a y a a c an a c a a n n n y a ata ni bli ni gi ta ija ta ke v bi YR si ri ni tan ni ru in ti nd tvi ni ar ki ni bli niks lba epu rme eor ekis rba enis Tur oldo Ser ia, F Rus ulga Bos khs ma ela kra Croa Pola La thua ung lova sto epu loveA R A G b ze moE R SBUiaBnMz RL H ShdoUz A urkyzKaecTcergzyaCKMjiTa10

Climate Change, Agriculture and Food SecurityAgriculture is the major component of theeconomy, representing some 24 percent of grossdomestic product (GDP), around 66 percentof employment, 26 percent of exports and 39percent of tax revenue. Agriculture is the mainlivelihood of rural families (64 percent of thepopulation), who produce food for their ownconsumption and, to some extent, for sale onurban markets.26 Since the times of the SovietUnion, cotton has been the main cash cropaccounting for 75-90 percent of agriculturalexports depending on the year.27Despite good rains and harvest in 2009, foodproduction in Tajikistan faces many serious challenges.Around 1.4 million people are food insecure and thelevel of severe food insecurity in the country is about 9percent of the rural population.28 “At the moment it isnot a critical situation but there is a high vulnerability.If there’s a shock people will lose their protectiveassets,” says Christophe Viltard, Oxfam Livelihoodsand Food Security Programme Co-ordinator.Shamsieva Anvaroi, a farmer in Ganchi District, north Tajikistan,says her pears are often affected by pests and she has to usegarlic in soil to help ward off diseases. Photo: Anita SwarupOne of the ways in which climate shocks such asdroughts, flooding and extreme weather conditionscreate cycles of disadvantage is through their impacton agricultural production. During the drought in2008, grain harvest totals were down between 30percent and 40 percent over the previous year29and in September 2008, the UN had to launch aHumanitarian Food Security Appeal. Many farmersreported losing their wheat crops and having tosell their livestock to buy food. When a droughtdestroys a harvest, the resulting loss of income andassets can leave households unable to afford theseed, fertilizer and other inputs needed to restoreproduction the following year. In Central and SouthAsia, crop yields are predicted to fall by up to 30 percent by 2050 due to climate change, creating a veryhigh risk of hunger in several countries.30“Last year it was a droughtbut this year is better.However there is still impactfrom last year’s drought.Most of the ‘dekhans’ orcollective farms are rainfedand still impacted from lastyear’s drought. If a dekhanfarmer is affected, hiscapacity to get seeds andfertilisers will be affected,”Hminov Poteh, Deputy Mayor,Timurmalik District.“I think the weather has become warmerin the last 4 or 5 years and that isaffecting our crops. The sickness of ourcrops is increasing but the pesticides areexpensive and we are losing almost 30percent of our crops to diseases –onion, tomato and cucumber.And the drought was very hard on thewheat crop last year.”Turaqulov Saidmuzator, a farmer inTemumalik District. Photo: Anita Swarup11Many farmers, community leaders and localgovernment have already observed more frequentdroughts. Qodirov Hudoi-Berdi, Deputy of Chief,Committee of Emergency Situations, Sugd Regionbelieves that droughts are getting worse. “Two yearsago there was a drought and the harvest was very bad.Every two or three years there’s been a drought in thelast ten years. There are some droughts that destroy100 percent of the crops and some droughts may be50 percent. If things get worse, we will recommend thatpeople store food now for the next year.”According to Ramazon Nematov, Head of Committeeof Emergencies, Kulyab Zone, “There was a loweryield from cotton and wheat in 2008 and peoplecould not get fodder for animals. They could notstore enough fodder, as 2006 and 2007 was dry aswell. Last year people lost their harvest, this year(2009) people don’t have seeds and also somerainfed lands have become dry.”Luckily for all the farmers in Tajikistan, there weregood rains in 2009 that meant food crops haveflourished. Shamsiddinovir Chinigul is a farmer inKaftarkhona Village in Vose District. Last year wasdifficult, she says (and she had received some foodvouchers from Oxfam) but this year she is happybecause there were good rains – and she managedto produce 5 sacks of potatoes.Shamsiddinovir Chinigul, a farmer from the Vose District.Photo: Anita SwarupSaodat, an Oxfam partner Improving Rural Women’s livelihoodsSince soil degradation is a serious challengein Tajikistan, soil conservation using naturaltechniques is one solution that helps preservemoisture in the soil. Omina Askarova (photo)is chief of the women’s ‘dekhan’

"It's not crisis point yet but it will be soon" Timur Idrisov, NGO, Little Earth, October 2009. This Oxfam report is based on interviews undertaken in communities in Spitamen and Ganchi in the north and Vose, Fakhor and Temurmalik in the south in October 2009. It gives an insight into how poor men and women