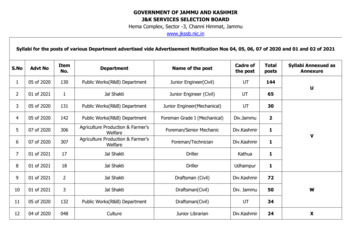

Transcription

SOCIAL SCIENCEITextbook of Political Science for Class X

SOCIAL SCIENCEITextbook ofPolitical Sciencefor Class XJammu & Kashmir Board Of School Education

First EditionNovember 2019#No part of this book may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system or transmitted,in any form or by any means, electronic,mechanical, photocopying, recording orotherwise without the prior permission ofthe publisher.#This book is sold subject to the conditionthat it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise disposed of inany form of binding or cover other than thatin which it is published without the writtenconsent of the publisher.Cover and LayoutShowkat A BabaProfessional Graphics Srinagar / 9419974394

FOREWORDCurriculum updating is a continuous process and hence theJammu and Kashmir Board of School Education has broughtout the revised curricula for different classes. Social Science isof crucial importance because it helps learners in understandingenvironment and socio Political scenario in a broader perspective anda reasonable outlook.The present Textbook has been developed in the light of NCF2005 guidelines. The Textbook developed on the basis of NCFsigni ies an attempt to discourage rote learning. The attempt has alsobeen made to link children's life at school and life outside the school.This Textbook of Social Science aims at enabling students to developcritical understanding of society to lay foundation for an analyticaland creative mindset relating to political developments. Change in thetext book entails the change in the content and pedagogical practice ofcurriculum. Main objective of this change is to enable the children tounderstand the society and the world in which we live, as well as, tocomprehend socio-political advancements.I appreciate the hard work done by the Academic Division andtextbook development committee responsible for development ofthis book. I acknowledge and place on record my deep appreciation tothe Director NCERT and Head curriculum Division, NCERT for theirsupport and cooperation. The contents in this book have beenadopted completely from the NCERT textbook of Social Science forclass X titled “Democratic Politics-II”.As an organization committed to systematic reform andcontinuous improvement in the quality of its textbooks, JK BOSEwelcomes comments and suggestions which will enable us toundertake further revision and re inement. I hope this textbook ofSocial Science shall sensitize learners about the Political perspectivein an explicit manner.(Prof.Veena Pandita)Chairperson

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTThe Jammu & Kashmir Board of School Education isgrateful to the following subject experts for theirhard work, dedication and contribution indeveloping the local content of this textbook.1.2.3.4.5.6.Dr.Aftab Khan, Ex. Principal GDC Kangan,KashmirMr. Paramjeet Singh, Asstt. Professor(PoliticalScience) GDC,JandrahMr.Rakesh Chowdhary, Asstt. Professor(PoliticalScience) GDC, UdhampurDr. Avineet , Lecturer in Pol. Science, SRML HSSJammuMs.Yamini Atrey, Lecturer in Pol Science BoysHSS Gandhi NagarMr.Manoj Raina,Ex.Lecturer in Pol. Science,School Education DepartmentMember CoordinatorsSyed Fayaz, Academic Officer-KDMr. Suresh Gouria , Academic Officer-JDThe J&K Board of School Education gratefullyacknowledges the use of content from NCERT textbookof Political Science for class X in the development ofthis textbook.I express my gratitude to Prof Veena Pandita( C h a i r p e r s o n ) fo r h e r s u p p o r t a n d h e l p i ndevelopment of this textbook. She has been a source ofinspiration for all of us and without her guidance, thisendeavour would have been impossible.I also extend my thanks to Prof. Abdul WahidMakhdoomi (Joint Secretary) Publication.My sincere gratitude is due to the CurriculumDevelopment & Research wing JD & KD for theiruntiring efforts for making this textbook available forthe students of class X.Suggestions from the stakeholders for theimprovement of the Textbook shall be highlyappreciated.(Dr. Farooq Ahmad Peer)Director Academics

ContentsUnit IChapter 1Power-sharing1Chapter 2Federalism13Unit IIChapter 3Democracy and Diversity29Chapter 4Gender, Religion and Caste39Unit IIIChapter 5Popular Struggles and Movements57Chapter 6Political Parties71Unit IVChapter 7Outcomes of Democracy89Chapter 8Challenges to Democracy101The Jammu & KashmirReorganization Act, 2019113Addendumv

Power-sharingP o w e r-s h a r i n gWith this chapter, we resume the tour of democracy that we startedlast year. We noted last year that in a democracy all power does notrest with any one organ of the government. An intelligent sharing ofpower among legislature, executive and judiciary is very important tothe design of a democracy. In this and the next two chapters, wecarry this idea of power-sharing forward. We start with two storiesfrom Belgium and Sri Lanka. Both these stories are about howdemocracies handle demands for power-sharing.The stories yield somegeneral conclusions about the need for power-sharing in democracy.This allows us to discuss various forms of power-sharing that will betaken up in the following two chapters.Chapter IOverview1

Belgium and Sri LankaI have a simpleequation in mind.Sharing power dividing power weakening thecountry. Why do westart by talking ofthis?Belgium is a small country in Europe,smaller in area than the state ofHaryana. It has borders with France,the Netherlands, Germany andLuxembourg. It has a population of alittle over one crore, about half thepopulation of Haryana. The ETHNICcomposition of this small country isvery complex. Of the country’s totalpopulation, 59 per cent lives in theFlemish region and speaks Dutchlanguage. Another 40 per cent peoplelive in the Wallonia region and speakFrench. Remaining one per cent of theBelgians speak German. In the capitalcity Brussels, 80 per cent people speakFrench while 20 per cent are Dutchspeaking.The minority French-speakingcommunity was relatively rich andpowerful. This was resented by theDutch-speaking community who gotthe benefit of economic developmentand education much later. This led totensions between the Dutch-speakingand French-speaking communitiesduring the 1950s and 1960s. Thetension between the two communitieswas more acute in Brussels. Brusselspresented a special problem: theDutch-speaking people constituted amajority in the country, but aminority in the capital.Let us compare this to thesituation in another country. SriLanka is an island nation, just a fewkilometres off the southern coast ofTamil Nadu. It has about two crorepeople, about the same as in Haryana.Like other nations in the South Asiaregion, Sri Lanka has a diversepopulation. The major social groupsare the Sinhala-speakers (74 per cent)and the Tamil-speakers (18 per cent).Among Tamils there are two subgroups. Tamil natives of the country2Ethnic: A socialdivision based onshared culture. Peoplebelonging to the sameethnic group believe intheir common descentbecause of similaritiesof physical type or ofculture or both. Theyneed not always havethe same religion ornationality. WikipediaD e m o c ra t i c Po l i t i c sCommunitiesandregions ofBelgiumBrussels-Capital RegionWalloon (French-speaking)Flemish (Dutch-speaking)German-speakingLook at the maps of Belgium and Sri Lanka. In whichregion, do you find concentration of differentcommunities?For more details, visit https://www.belgium.be/en

are called ‘Sri Lankan Tamils’ (13 per cent).The rest, whose forefathers came fromIndia as plantation workers duringcolonial period, are called ‘Indian Tamils’.As you can see from the map, Sri LankanTamils are concentrated in the north andeast of the country. Most of the Sinhalaspeaking people are Buddhists, whilemost of the Tamils are Hindus orMuslims. There are about 7 per centChristians, who are both Tamiland Sinhala.Just imagine what could happenin situations like this. In Belgium, theDutch community could takeadvantage of its numeric majority andforce its will on the French andGerman-speaking population. Thiswould push the conflict amongcommunities further. This could leadto a very messy partition of thecountry; both the sides would claimcontrol over Brussels. In Sri Lanka, theSinhala community enjoyed an evenbigger majority and could impose itswill on the entire country. Now, let uslook at what happened in both thesecountries.Majoritarianism in Sri LankaIn 1956, an Act was passed torecognise Sinhala as the only officiallanguage, thus disregarding Tamil. Thegovernments followed preferentialpolicies that favoured Sinhalaapplicants for university positions andgovernment jobs. A new constitutionstipulated that the state shall protectand foster Buddhism.All these government measures,coming one after the other, graduallyincreased the feeling of alienationamong the Sri Lankan Tamils. They feltthat none of the major political partiesled by the Buddhist Sinhala leaders wassensitive to their language and culture.They felt that the constitution andgovernment policies denied them equalpolitical rights, discriminated againstthem in getting jobs and otheropportunities and ignored theirinterests. As a result, the relationsEthnic Communitiesof Sri LankaSinhaleseSri Lankan TamilIndian TamilMuslimFor more details, visit https://www.gov.lkMajoritarianism: Abelief that the majoritycommunity should beable to rule a country inwhichever way it wants,by disregarding thewishes and needs of theminority.P o w e r-s h a r i n gSri Lanka emerged as an independentcountry in 1948. The leaders of theSinhala community sought to securedominance over government by virtueof their majority. As a result, thedemocratically elected governmentadopted a series of MAJORITARIANmeasures to establish Sinhala supremacy.3

What’s wrong ifthe majoritycommunityrules? If Sinhalasdon’t rule in SriLanka, whereelse will theyrule?between the Sinhala and Tamilcommunities strained over time.The Sri Lankan Tamils launchedparties and struggles for the recognitionof Tamil as an official language, forregional autonomy and equality ofopportunity in securing education andjobs. But their demand for moreautonomy to provinces populated bythe Tamils was repeatedly denied. By1980s several political organisationswere formed demanding anindependent Tamil Eelam (state) innorthern and eastern parts of Sri Lanka.The distrust between the twocommunities turned into widespreadconflict. It soon turned into a CIVIL WAR.As a result thousands of people of boththe communities have been killed. Manyfamilies were forced to leave the countryas refugees and many more lost theirlivelihoods. You have read (Chapter 1of Economics textbook, Class X) aboutSri Lanka’s excellent record of economicdevelopment, education and health. Butthe civil war has caused a terrible setbackto the social, cultural and economic lifeof the country. It ended in 2009.Accommodation in Belgium4 Constitution prescribes that thenumber of Dutch and French-speakingministers shall be equal in the centralgovernment. Some special laws requirethe support of majority of membersfrom each linguistic group. Thus, noWhat kind of a solution isthis? I am glad ourConstitution does not saywhich minister will come fromwhich community.single community can make decisionsunilaterally. Many powers of the centralgovernment have been given to stategovernments of the two regions of thecountry. The state governments are notsubordinate to the Central Government. Brussels has a separate governmentin which both the communities haveequal representation. The Frenchspeaking people accepted equalrepresentation in Brussels because theDutch-speaking community hasaccepted equal representation in theCentral Government. WikipediaD e m o c ra t i c Po l i t i c sCivil war: A violentconflict betweenopposing groups withina country that becomesso intense that it appearslike a war.The Belgian leaders took a differentpath. They recognised the existence ofregional differences and culturaldiversities. Between 1970 and 1993,they amended their constitution fourtimes so as to work out an arrangementthat would enable everyone to livetogether within the same country. Thearrangement they worked out isdifferent from any other country andis very innovative. Here are some ofthe elements of the Belgian model:The photograph here is of a streetaddress in Belgium. You will notice thatplace names and directions in twolanguages – French and Dutch.

Apart from the Central andthe State Government, there is athird kind of government. This‘community government’ is elected bypeople belonging to one languagecommunity – Dutch, French andGerman-speaking – no matter wherethey live. This government has thepower regarding cultural, educationaland language-related issues.European Parliament in Brussels, BelgiumUnion, Brussels was chosen as itsheadquarters.Read any newspaper for one week and make clippings ofnews related to ongoing conflicts or wars. A group of fivestudents could pool their clippings together and do the following: Classify these conflicts by their location (your State/UT, India,outside India). Find out the cause of each of these conflicts. How many ofthese are related to power sharing disputes? Which of these conflicts could be resolved by working out powersharing arrangements?What do we learn from these two storiesof Belgium and Sri Lanka? Both aredemocracies. Yet, they dealt with thequestion of power sharing differently.In Belgium, the leaders have realisedthat the unity of the country is possibleonly by respecting the feelings andinterests of different communities andregions. Such a realisation resulted inmutually acceptable arrangements forsharing power. Sri Lanka shows us acontrasting example. It shows us thatif a majority community wants to forceits dominance over others and refusesto share power, it can undermine theunity of the country.So you aresaying thatsharing of powermakes us morepowerful. Soundsodd! Let methink.P o w e r-s h a r i n gYou might find the Belgian modelvery complicated. It indeed is verycomplicated, even for people living inBelgium. But these arrangements haveworked well so far. They helped toavoid civic strife between the twomajor communities and a possibledivision of the country on linguisticlines. When many countries of Europecame together to form the European5

Tab - The Calgary Sun, Cagle Cartoons Inc.Why power sharing is desirable?D e m o c ra t i c Po l i t i c sThus, two different sets of reasons canbe given in favour of power sharing.Firstly, power sharing is good becauseit helps to reduce the possibility ofconflict between social groups. Sincesocial conflict often leads to violenceand political instability, power sharingis a good way to ensure the stabilityof political order. Imposing the willof majority community over othersmay look like an attractive option inthe short run, but in the long run itundermines the unity of the nation.Tyranny of the majority is not just6Prudential: Based onprudence, or on carefulcalculation of gains andlosses. Prudential decisionsare usually contrasted withdecisions based purely onmoral considerations.The cartoon at the left refers to theproblems of running the Germany’s grandcoalition government that includes the twomajor parties of the country, namely theChristian Democratic Union and theSocial Democratic Party. The two partiesare historically rivals to each other. Theyhad to form a coalition governmentbecause neither of them got clear majorityof seats on their own in the 2005elections. They take divergent positionson several policy matters, but still jointlyrun the government.For details about the German Parliament,visit https://www.bundestag.de/enoppressive for the minority; it oftenbrings ruin to the majority as well.There is a second, deeper reasonwhy power sharing is good fordemocracies. Power sharing is the veryspirit of democracy. A democratic ruleinvolves sharing power with thoseaffected by its exercise, and who haveto live with its effects. People have aright to be consulted on how they areto be governed. A legitimategovernment is one where citizens,through participation, acquire a stakein the system.Let us call the first set of reasonsPRUDENTIAL and the second moral. Whileprudential reasons stress that powersharing will bring out better outcomes,moral reasons emphasise the very actof power sharing as valuable.Annette studies in a Dutch medium school in thenorthern region of Belgium. Many French-speaking students inher school want the medium of instruction to be French. Selvistudies in a school in the northern region of Sri Lanka. All thestudents in her school are Tamil-speaking and they want themedium of instruction to be Tamil.If the parents of Annette and Selvi were to approachrespective governments to realise the desire of the childwho is more likely to succeed? And why?

Khalil’sdilemmaAs usual, Vikram was driving the motorbike under a vow ofsilence and Vetal was the pillion rider. As usual, Vetalstarted telling Vikram a story to keep him awake whiledriving. This time the story went as follows:“In the city of Beirut there lived a man called Khalil. His parents camefrom different communities. His father was an Orthodox Christian and mother a SunniMuslim. This was not so uncommon in this modern, cosmopolitan city. People fromvarious communities that lived in Lebanon came to live in its capital, Beirut. They livedtogether, intermingled, yet fought a bitter civil war among themselves. One of Khalil’suncles was killed in that war.At the end of this civil war, Lebanon’s leaders came together and agreed to some basicrules for power sharing among different communities. As per these rules, the country’sPresident must belong to the Maronite sect of Catholic Christians. The Prime Minister mustbe from the Sunni Muslim community. The post of Deputy Prime Minister is fixed forOrthodox Christian sect and that of the Speaker for Shi’a Muslims. Under this pact, theChristians agreed not to seek French protection and the Muslims agreed not to seekunification with the neighbouring state of Syria.When the Christians and Muslims came tothis agreement, they were nearly equal in population. Both sides have continued torespect this agreement though now the Muslims are in clear majority.Khalil does not like this system one bit. He is a popular man with political ambition. Butunder the present system the top position is out of his reach. He does not practiseeither his father’s or his mother’s religion and does not wish to be known by either. Hecannot understand why Lebanon can’t be like any other ‘normal’ democracy. “Just holdan election, allow everyone to contest and whoever wins maximum votes becomes thepresident, no matter which community he comes from. Why can’t we do that, like inother democracies of the world?” he asks. His elders, who have seen the bloodshed ofthe civil war, tell him that the present system is the best guarantee for peace ”The story was not finished, but they had reached the TV towerwhere they stopped every day. Vetal wrapped upquickly and posed his customary question toVikram: “If you had the power to rewritethe rules in Lebanon, what would you do?the old rules? Or do something else?” Vetaldid not forget to remind Vikram of their basicpact: “If you have an answer in mind and yetdo not speak up, your mobike will freeze, andso will you!”Can you help poor Vikram in answering Vetal?P o w e r-s h a r i n gWould you adopt the ‘regular’ rules followedeverywhere, as Khalil suggests? Or stick to7

Forms of power-sharingThe idea of power-sharing hasemerged in opposition to the notionsof undivided political power. For along time it was believed that all powerof a government must reside in oneperson or group of persons locatedat one place. It was felt that if thepower to decide is dispersed, it wouldnot be possible to take quick decisionsand to enforce them. But thesenotions have changed with theemergence of democracy. One basicprinciple of democracy is that peopleare the source of all political power.In a democracy, people rulethemselves through institutions ofself-government. In a good democraticgovernment, due respect is given todiverse groups and views that exist ina society. Everyone has a voice in theshaping of public policies. Therefore,it follows that in a democracy political8 Olle Johansson - Sweden, Cagle Cartoons Inc., 25 Feb. 2005D e m o c ra t i c Po l i t i c sReigning the ReinsIn 2005, some new laws were made in Russia giving more powers toits president. During the same time the US president visited Russia.What, according to this cartoon, is the relationship between democracyand concentration of power? Can you think of some other examples toillustrate the point being made here?power should be distributed among asmany citizens as possible.In modern democracies, powersharing arrangements can take manyforms. Let us look at some of the mostcommon arrangements that we haveor will come across.1 Power is shared among differentorgans of government, such as thelegislature, executive and judiciary. Letus call this horizontal distribution ofpower because it allows different organsof government placed at the same levelto exercise different powers. Such aseparation ensures that none of theorgans can exercise unlimited power.Each organ checks the others. Thisresults in a balance of power amongvarious institutions. Last year, we studiedthat in a democracy, even thoughministers and government officialsexercise power, they are responsible tothe Parliament or State Assemblies.Similarly, although judges are appointedby the executive, they can check thefunctioning of executive or laws madeby the legislatures. This arrangement iscalled a system of checks and balances.2 Power can be shared amonggovernments at different levels – ageneral government for the entirecountry and governments at theprovincial or regional level. Such ageneral government for the entirecountry is usually called federalgovernment. In India, we refer to itas the Central or Union Government.The governments at the provincial orregional level are called by differentnames in different countries. In India,

3 Power may also be shared amongdifferent social groups such as thereligious and linguistic groups.‘Community government’ in Belgiumis a good example of this arrangement.In some countries there areconstitutional and legal arrangementswhereby socially weaker sections andwomen are represented in thelegislatures and administration. Lastyear, we studied the system of ‘reservedconstituencies’ in assemblies and theparliament of our country. This typeof arrangement is meant to give spacein the government and administrationto diverse social groups who otherwisewould feel alienated from thegovernment. This method is used togive minority communities a fair sharein power. In Unit II, we shall look atvarious ways of accommodating socialdiversities.4 Power sharing arrangements canalso be seen in the way politicalparties, pressure groups andmovements control or influence thosein power. In a democracy, the citizensmust have freedom to choose amongvarious contenders for power. Incontemporary democracies, this takesthe form of competition amongdifferent parties. Such competitionensures that power does not remain inone hand. In the long run, power isshared among different political partiesthat represent different ideologies andsocial groups. Sometimes this kind ofsharing can be direct, when two ormore parties form an alliance tocontest elections. If their alliance iselected, they form a coalitiongovernment and thus share power. Ina democracy, we find interest groupssuch as those of traders, businessmen,industrialists, farmers and industrialworkers. They also will have a share ingovernmental power, either throughparticipation in governmentalcommittees or bringing influence onthe decision-making process. In UnitIII, we shall study the working ofpolitical parties, pressure groups andsocial movements.In my school, theclass monitorchanges everymonth. Is thatwhat you call apower sharingarrangement?P o w e r-s h a r i n gwe call them State Governments. Thissystem is not followed in all countries.There are many countries where thereare no provincial or stategovernments. But in those countrieslike ours, where there are differentlevels of government, theconstitution clearly lays down thepowers of different levels ofgovernment. This is what they did inBelgium, but was refused in Sri Lanka.This is called federal division ofpower. The same principle can beextended to levels of governmentlower than the State government, suchas the municipality and panchayat. Letus call division of powers involvinghigher and lower levels ofgovernment vertical division ofpower. We shall study these at somelength in the next chapter.9

D e m o c ra t i c Po l i t i c s 10Exercises Here are some examples of power sharing. Which of the four types of powersharing do these represent? Who is sharing power with whom?The Bombay High Court ordered the Maharashtra state government to immediatelytake action and improve living conditions for the 2,000-odd children at sevenchildren’s homes in Mumbai.The government of Ontario state in Canada has agreed to a land claim settlement withthe aboriginal community. The Minister responsible for Native Affairs announced thatthe government will work with aboriginal people in a spirit of mutual respect andcooperation.Russia’s two influential political parties, the Union of Right Forces and the LiberalYabloko Movement, agreed to unite their organisations into a strong right-wingcoalition. They propose to have a common list of candidates in the nextparliamentary elections.The finance ministers of various states in Nigeria got together and demanded thatthe federal government declare its sources of income. They also wanted to know theformula by which the revenue is distributed to various state governments.1. What are the different forms of power sharing in moderndemocracies? Give an example of each of these.2. State one prudential reason and one moral reason for powersharing with an example from the Indian context.3. After reading this chapter, three students drew differentconclusions. Which of these do you agree with and why? Giveyour reasons in about 50 words.Thomman - Power sharing is necessary only in societieswhich have religious, linguistic or ethnic divisions.Mathayi – Power sharing is suitable only for big countries thathave regional divisions.Ouseph – Every society needs some form of power sharingeven if it is small or does not have social divisions.4. The Mayor of Merchtem, a town near Brussels in Belgium, hasdefended a ban on speaking French in the town’s schools. Hesaid that the ban would help all non-Dutch speakers integratein this Flemish town. Do you think that this measure is inkeeping with the spirit of Belgium’s power sharingarrangements? Give your reasons in about 50 words.

6. Different arguments are usually put forth in favour of and againstpower sharing. Identify those which are in favour of power sharingand select the answer using the codes given below? Power sharing:A.B.C.D.E.F.G.reduces conflict among different communitiesdecreases the possibility of arbitrarinessdelays decision making processaccommodates diversitiesincreases instability and divisivenesspromotes people’s participation in governmentundermines the unity of a country(a)(b)(c)(d)AAABBCBCDEDDFFGG7. Consider the following statements about power sharingarrangements in Belgium and Sri Lanka.A. In Belgium, the Dutch-speaking majority people tried to imposetheir domination on the minority French-speaking community.B. In Sri Lanka, the policies of the government sought to ensure thedominance of the Sinhala-speaking majority.C. The Tamils in Sri Lanka demanded a federal arrangement ofpower sharing to protect their culture, language and equality ofopportunity in education and jobs.D. The transformation of Belgium from unitary government to afederal one prevented a possible division of the country onlinguistic lines.Which of the statements given above are correct?(a) A, B, C and D(b) A, B and D(c) C and D(d) B, C and DP o w e r-s h a r i n g“We need to give more power to the panchayats to realisethe dream of Mahatma Gandhi and the hopes of the makersof our Constitution. Panchayati Raj establishes truedemocracy. It restores power to the only place where powerbelongs in a democracy – in the hands of the people. Givingpower to Panchayats is also a way to reduce corruption andincrease administrative efficiency. When people participate inthe planning and implementation of developmental schemes,they would naturally exercise greater control over theseschemes. This would eliminate the corrupt middlemen. Thus,Panchayati Raj will strengthen the foundations of ourdemocracy.”Exercises5. Read the following passage and pick out any one of theprudential reasons for power sharing offered in this.11

8. Match List I (forms of power sharing) with List II (forms of government)and select the correct answer using the codes given below in the lists:12ExercisesD e m o c ra t i c Po l i t i c s1.List IList IIPower shared among differentorgans of governmentA. Community government2.Power shared among governmentsat different levelsB. Separation of powers3.Power shared by different socialgroupsC. Coalition governmentPower shared by two or morepolitical partiesD. Federal government4.(a)(b)(c)(d)1DBBC2ACDD3BDAA4CACB9. Consider the following two statements on power sharing andselect the answer using the codes given below:A. Power sharing is good for democracy.B. It helps to reduce the possibility of conflict between social groups.Which of these statements are true and false?(a)(b)(c)(d)A is true but B is falseBoth A and B are trueBoth A and B are falseA is false but B is true

In the previous chapter, we noted that vertical division of power amongdifferent levels of government is one of the major forms of powersharing in modern democracies. In this chapter, we focus on this formof power-sharing. It is most

French while 20 per cent are Dutch-speaking. The minority French-speaking community was relatively rich and powerful. This was resented by the Dutch-speaking community who got the benefit of economic development and education much later. This led to tensions between the Dutch-speaking and French-speaking communities during the 1950s and 1960s. The