Transcription

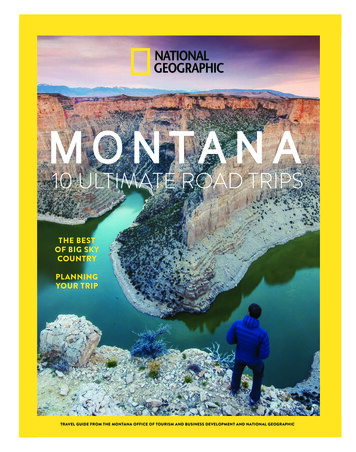

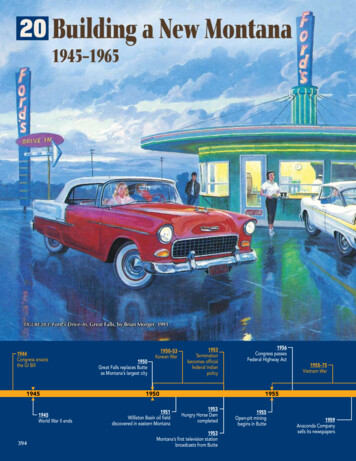

FIGURE 20.1: Ford’s Drive-In, Great Falls, by Brian Morger, 19911944Congress enactsthe GI Bill19451945World War II ends3941950Great Falls replaces Butteas Montana’s largest city1950–53Korean War1953Terminationbecomes officialfederal Indianpolicy19501951Williston Basin oil fielddiscovered in eastern Montana1956Congress passesFederal Highway Act1955–75Vietnam War19551953Hungry Horse Damcompleted1953Montana’s first television stationbroadcasts from Butte1955Open-pit miningbegins in Butte1959Anaconda Companysells its newspapers

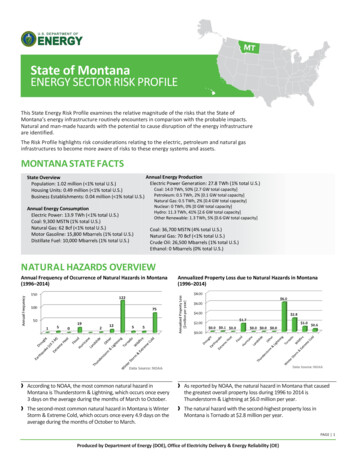

READ TO FIND OUT: How the nation’s largest economic boomaffected Montana Why the Anaconda Company dug theBerkeley Pit Why more rural Montanans moved into town How fear of communism affected everyday lifeThe Big PictureThe great economic boom after World War II broughtmodern conveniences and new anxieties—and shapedMontana into the place we know today.In the spring of 1945 a Sheridan County farm wife named AnnaDahl strode into the federal headquarters of the Rural ElectrificationAdministration in Washington, D.C. She plunked down a fistful ofpaperwork: a federal loan application that would enable the people of Sheridan County to string power lines across the northeastcorner of Montana. A year later 600 families in Sheridan, Roosevelt,and Daniels Counties could switch on a light and read in bed.Many changes swept across Montana in the years afterWorld War II. Electricity lit up rural areas. Interstate highwaysthreaded across the land. Commercial airline travel became popular. Montanans bought their first televisions. People could travelmore easily and get information faster. Everybody’s life changedin some way.During this time the nation’s economy boomed like neverbefore. After World War II, the United States enjoyed the greatestgrowth in prosperity in its history. The average American becamewealthier than ever before.1962Cuban Missile Crisis1964Congresspasses theWilderness Act19601968Congress passesIndian Civil Rights Act1971Chilean government takespossession of theAnaconda Company’sbiggest mine19651961Air Force begins constructionof Montana ICBM silos1972Montana adoptsnew constitution19701966Large-scale strip miningbegins at Colstrip1965Yellowtail Dam completed1970First Earth Daycelebrated19751975Libby Dam completed1970Several major railroads merge20 — BUILDING A NEW MONTANA395395

Montana’s economy boomed, too. But most of the nation’s growthhappened outside Montana, and in industries Montana did not have.By the end of this period, Montana’s economy fell behind the rest ofthe nation’s. Meanwhile dams, strip mines, and a large open-pit mine atButte changed the landscape.The modernization of Montana is a complicated story. Many thingshappened in the 1950s and 1960s that made Montanans’ lives easier. Butthese years also brought new difficulties. In many ways big and small,people during this period watched their state transform into the modernMontana we know today.A Postwar Boom Sweeps the NationFIGURE 20.2: Soldiers returned fromWorld War II eager to get married, buya house and a car, and build a new life.This couple is celebrating their honeymoon in Yellowstone National Park.The United States emerged from World War II as a superpower (anation with greater economic, political, and military power than mostnations). Its industries remained productive, its military was one of themost powerful in the world, and the GI Bill gave the nation’s economyan enormous boost (see Chapter 19).After a decade of depression and war rationing (limitingpeople’s access to goods or food), people were ready to spend money.Consumerism (the idea that buying consumer goods benefits theeconomy) became an economic strategy for the nation. You could helpkeep America strong by buying more goods.The population exploded as veterans returned from the war, gotmarried, and started families. In 1948 a baby was born in America every8 seconds. The baby boom (a dramatic increase in the number ofbabies born) created even more economic activity. Americans boughtnew cars, strollers, and refrigerators and built new houses,stores, hospitals, and schools.With more people spendingmore money than ever before,the United States experiencedthe largest peacetime economicexpansion in its history. Neverbefore had Americans been sowell-off.Montana Suppliesthe Great BoomMontana’s lumber, plywood,and other timber productshelped build new houses andfactories. New lumber millsopened to fill the nation’s grow-396PART 4: THE MODERN MONTANA

ing demand for building supplies. Logging companies clear-cut broadswaths of Montana’s forests. Timber towns like Libby and Missoula grew.Montana copper went into telephone wires, plumbing, and carengines. Aluminum became the new modern metal. In 1955 the AnacondaCompany opened an aluminum plant near Columbia Falls. It providedlow-cost siding for new homes—as well as for hundreds of other modernproducts from kitchen foil to space capsules.Montana’s oil fields expanded to produce oil for all the newmachines, heat for houses, and gasoline for cars. Montana’s biggest oilfields—Kevin-Sunburst near Shelby, Cat Creek near Lewistown, and ElkBasin southeast of Red Lodge—burst into high activity.In 1951 discovery of a huge new oil field at Williston Basin, onMontana’s eastern border, doubled Montana’s oil production. Townslike Glendive and Sidney boomed. Billings became the center of activityfor Montana’s oil business.Refineries in Billings and Laurel dramatically increased their production. By 1957 Montana’s petroleum earned more revenue (income)than even copper. By 1960 Montana was the 12th biggest oil-producingstate in the country.Montana’s wheat and beef helped feed the growing U.S. population.Crops and cattle herds flourished. Farmers began using more machinerylike combines, mechanical hay balers, and large motorized tractors topull them. Ranchers began timing their calving season to fit with market demands. Scientific developmentsintroduced new fertilizers, pesticides,and drought-resistant strains of grain,which all helped increase profits.FIGURE 20.3: More people than evercould afford new automobiles in the1950s, and everybody wanted one.This Butte Chevrolet dealer sponsoreda special promotion that drew a crowdof customers.Dams: Power andWater to a Thirsty LandAll the new houses and emerging businesses needed power. And Montana’smodernizing farms needed irrigation.With three big river systems flowingboth east and west, Montana beganbuilding more dams to produce both.Dam building began in Montana in1890, when a Great Falls water company built Black Eagle Dam across theMissouri River. Other dams followed.Many Montanans supported dambuilding projects. Dams providedirrigation to farmland, generatedhydroelectric power (electricity20 — BUILDING A NEW MONTANA397

FIGURE 20.4: At 525 feet tall, theYellowtail Dam is the tallest damon the Missouri River system. A fewyears after it was completed, a stretchof the Bighorn River below the dambecame a popular trout fishing spot,but the dam itself remains controversial.generated by water flow), and controlled downstream flooding. Damconstruction brought federal money into Montana and provided jobsthat supported local communities. But dams also created reservoirs thatflooded out farms, homes, historic sites, and even towns.Between the early 1930s and the late 1960s, the state and federal governments built 48 dams in Montana. The Fort Peck Dam, completed in1939, was the biggest (see Chapter 18). Second in size was the HungryHorse Dam. It spans the South Fork of the Flathead River, northeast ofKalispell. When completed, in 1953, the dam provided electric power tothe aluminum plant owned by the Anaconda Company at cheaper ratesthan Montana Power could offer.The Hungry Horse Dam changed Montana’s politics, its landscape,and its economy. When Anaconda began buying its power from thefederally owned dam, Montana Power lost its biggest customer. Thepartnership between these twopowerful companies that haddominated the state for yearsbegan to break apart.Yellowtail Dam:Enduring ControversyThe Yellowtail Dam, completed in1965, generated years of controversy. The government first surveyed the Bighorn River, on theCrow Indian Reservation, in 1905to see if a dam there could provide irrigation to the surrounding land. Government leaderswanted to build the dam. Butthe Crow tribe owned the land.Crow leaders wanted to retain ownership of the damsite and lease it to someone tobuild a dam. That way, theywould receive annual payments to benefit the tribe. Butgovernment leaders believedthat the Bighorn River—andthe power that came from it—belonged to all the people, notjust the Crow.Crow leader RobertYellowtail (who served terms astribal chairman in the 1940s and398PART 4: THE MODERN MONTANA

1950s) fought for many years forthe tribe’s right to have final control over the dam site. But someCrow wanted the dam project tomove along. In 1955 the Crowtribe voted to sell the dam siteto the government for 5 million(equal to 37.6 million today). Inthe end the government paid 2.5 million. Construction beganin 1963 and was completed twoyears later. The federal government named the new dam afterRobert Yellowtail, even thoughit had defied (gone against)his wishes.Libby Dam: Changed Land, Changed AttitudesFIGURE 20.5: The Libby Dam floodedOther dams also dramatically changed the landscape and the lives ofthe people living nearby. The Libby Dam, on the Kootenai River, created90-mile-long Lake Koocanusa. Workers cleared 28,000 acres of forest tomake room for the reservoir. The government bought the land, houses,and buildings that would be flooded. It moved the whole town of Rexfordseveral miles east, building by building. People who lived in Warland,Ural, and Gateway left their homes and moved to other towns.When construction on the Libby Dam began, most people living inthe region supported the project. They were excited to be a part of something big that brought energy, safety from floods, and new economicopportunities to Montana.But even before Libby Dam was completed, in the 1970s, publicattitude changed. Across the country, people began to think about theenvironmental damage that big projects like dams caused. They beganto question the value of projects like the Libby Dam, which providedbenefits but also damaged the environment. As Jim Morey of Libby said,“I hated to see the valley flooded. The tradeoff for electricity was wortha lot, but the old valley was worth a lot too.”90 miles of the Kootenai River Valley,creating Lake Koocanusa. Montana’slongest and tallest auto bridge spansthe lake, connecting a small Amishcommunity on the west side withthe Yaak Valley on the east side.Montana ModernizesRemember Anna Dahl, the Sheridan County farm wife, from the beginning of this chapter? Anna and her husband, Andrew Dahl, raised fivechildren on their 640-acre Sheridan County farm. No one knew therigors of living without electric power better than Anna Dahl did.“When the best years of our lives have been spent carrying coal,wood ashes and water, and when all the work within and without the20 — BUILDING A NEW MONTANA399

home was done by muscle power—ifyou had it—and grit if you didn’t, thechange to cooking, cleaning, washingand ironing with electricity . . . is almost“As a child I learned practical rules about electricity. Onebeyond comprehension,” she said.does not begin a baking project in a thunderstorm withAt the end of World War II, onlyan electric cookstove. When a lightning strike makes theabout half of Montana’s farms andphone jangle, don’t answer. When black clouds boil overrural areas had electricity supplied bythe horizon, unplug the television . . . No one dependeda power company. Many farm famion electricity for heat, and no one threw away the lanternslies generated their own electricity withor tore down the outhouse when it arrived.”windmills or gas-powered generators.—JUDY BLUNT, WHO GREW UP ON A PHILLIPS COUNTYRANCH IN THE 1960SIn the 1930s the governmentestablished the Rural ElectrificationAdministration, which provided loans to bring electricity into ruralAmerica. But private power companies like Montana Power did notFIGURE 20.6: Telephones helped ruralwant to build power lines into rural areas or across rugged terrain.families spread news and informationPeople lived too far apart, and there were too few rural customers toinstantly among neighbors who lived farapart. This ranch woman on the Circlemake it profitable.U Ranch might have been checking on aSo farmers and ranchers got together and did the work themselves.sick neighbor, phoning in a grocery order,or simply listening in on the party line.They formed rural electric cooperatives (companies that are owned bythe people who use them). These cooperativesgot their own loans and built power lines toplaces like Geraldine and Alzada.By the 1970s you could switch on lights,electric irons, water pumps, and washingmachines in almost every rural householdin Montana. And with electricity came yardlights, hot water heaters, electric water pumps,and indoor toilets.One Does Not Begin a BakingProject in a ThunderstormTelephones Make New ConnectionsMost Montana towns had telephone serviceafter 1910, but it took much longer for phonelines to reach out into the country. In 1945only 20 percent of Montana’s rural households had telephones. Farmers and rancherswere eager for phone service, which wouldconnect them to people far away.Starting in the 1940s, rural communitiesformed telephone cooperatives that workedthe same way electric cooperatives did, andoften used the same utility poles. By 1970almost every rural Montana household had aphone on the wall.Most rural phone lines were “party lines,”400PART 4: THE MODERN MONTANA

which meant that several families shared the same line.When a call came through, the phone would ring inall the houses on the line. Each party had a separatering pattern so everyone knew whom the call was for.Often they all picked up anyway and listened in on oneanother’s calls. People knew not to say anything on thephone that they did not want neighbors to hear.“Television transformed Americansocial habits . . . When a popularshow was on, all the toilets in thenation flushed at the same time,during commercial breaks andwhen the program ended.—STEVE GILLON, BOOMER NATION (2004)Radio and Television:Tuning in to the World“”Back in 1954 and 1955, we would clear everything off the air to accommodate the World’sSeries games. As we had no other way of gettingthese network shows in, we would film the gamesright off a picture tube in Fargo, North Dakota,and fly the films to Great Falls on National Guardplanes, hoping we didn’t lose too much time.Television connected Montanansto the rest of the world in awhole new way. They could seefootage of important events thathappened far away—like the assassination of President John F.Kennedy in 1963 and the firstwalk on the moon in 1969. As—W. C. “BUD” BLANCHETTE, MANAGER OF KFBB-TV, GREAT FALLSthe 1960s progressed, closeup images of the Vietnam War on the evening news deeply affectedeveryone.The first commercial TV stations started broadcasting in New Yorkin 1941. But until the 1950s Montanans could see television only if theytraveled somewhere else. In 1953 KXLF-TV of Butte became Montana’sfirst commercial TV station. Soon stations in Billings, Missoula, andGreat Falls were broadcasting the evening news and two or three hoursof locally produced programs. Montanans raced to the store to buytelevisions. They hung coat hangers and bed springs out their windowsto serve as antennas.Television and radio gave Montanans access to outside news reports.Until 1959 the Anaconda Company owned all the daily newspapersin every major city except Great Falls. Radio and television newscastsmeant that the Company no longer controlled how Montanans got theirnews. In 1959 the Anaconda Company sold its chain of papers.”More Women Went to WorkAmerica’s new prosperity changed people’s lifestyles. More womenbegan to work outside the home during this period than at any othertime in U.S. history. In 1940 about 16 percent of Montana’s working-agewomen held jobs. By 1960 more than 30 percent were working.Some women went to work to help pay for their families’ homes,cars, and televisions. Some found work more fulfilling than stayinghome. And some had to work to feed their families.Working women changed family life, towns, and the economy of20 — BUILDING A NEW MONTANA4 01

Montana. They owned and drove cars and bought more consumeritems. They even changed what their families ate. Women began buyingprepared foods like chicken pot pies (developed in 1951) and fast-cookrice (developed in 1950) because they had less time to prepare familymeals. Fast-food restaurants appeared in the 1950s for the working families who could afford to eat out.Some farm women moved into town for the week to work andcame home to the farm on weekends. But there were not many jobopportunities besides farm work for women in rural Montana. Mostrural Montanans—both men and women—continued to support theirfamilies on what they could raise on their farms and ranches.The Youth Culture Is BornFIGURE 20.7: Young Montanans enjoyednew activities together like roller skating,bowling, and just hanging out. Here theSpinning Marvels perform at the MariasFair in Shelby in 1958.In town, middle-class teenagers enjoyed new freedoms that came withcars and pocket money. Teens gathered at burger joints and at secludedspots on the edge of their town just to be together away from adults.The mass media (communication technologies that can reach millions of people) like television and radio helped create a music industryaimed just at young people. Transistor radios (small, portable radiosthat run on batteries), invented in the 1950s, gave young people theirfirst opportunity to tune into their own music away from the family living room. Teenagers in Montana and across the country listened to newsounds like rock and roll. A youth culture emerged—a feeling amongurban young people that they had more in commonwith one another than with older people, even in theirown families or communities.Montana EconomyFalls BehindIn 1950 thousands of Montanans held high-payingindustrial jobs. Most industrial workers belonged tolabor unions. The average Montanan earned 8 percentmore in per-capita income (the average annual income per person) than other Americans.But as America’s great boom continued, the national economy grew much faster than Montana’s.Montana was too far from major markets to attractthe booming factories that other states had. Montana’seconomy fell behind.By 1968 Montanans earned 14 percent less than thenational average. One reason was that other states’ industries were booming. Another reason was that twoof Montana’s most important industries—copper andthe railroads—changed dramatically.402PART 4: THE MODERN MONTANA

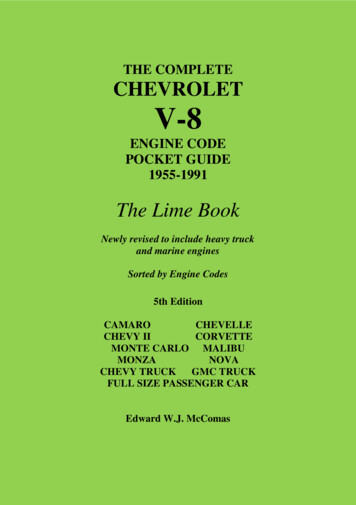

From Hard-Rock Miningto the Berkeley Pit“When you graduated from high school, youwere assured of three gifts. Some benevolent[generous] person in your family would give youa lunch bucket, somebody else would give you athermos, and you could go down on the smelterroad and get a slip and go to work. Everybodywent to work for the Company.The biggest changes happenedat the Anaconda Company.Anaconda emerged from WorldWar II a huge and powerful company. With mines in Montanaand Chile, it was the largest pro—HOWIE ROSENLEAF, AN ANACONDA SMELTER WORKER IN THE 1950Sducer of copper in the world. Itwas also Montana’s single largestemployer, providing jobs for thousands of workers across the state—2,500 at the Anaconda smelter alone. In 70 years Anaconda Copper hadearned 2.5 billion from Montana’s natural resources.But by the 1950s most of Anaconda’s profits came from Chile.Montana produced only 15 percent of the company’s copper. SoAnaconda shifted its attention away from Montana. It began to phase outunderground mining, which targeted high-grade copper veins and required thousands of skilled miners. In 1955 it began open-pit mining(removing low-grade ore using huge earth-moving equipment). Thiswas the birth of Butte’s Berkeley Pit.FIGURE 20.8: Butte’s Berkeley PitOpen-pit mining transformed both the land and the labor force ofswallowed up neighborhoods and toreat people’s sense of community. DumpButte. Thousands of hard-rock miners lost their jobs; most moved away.trucks removing dirt from the pit buriedButte lost population and political power. And as the pit expanded, itthe McQueen neighborhood’s HolySavior School.consumed part of Butte, too.”20 — BUILDING A NEW MONTANA403

“In the four years I spent traveling back and forth toMalta High School, the population of our community had dwindled by a third as the smaller, moremarginal places were absorbed by their larger neighbors . . . Overnight, it seemed, the place I grew upon had fallen under the wheels of big business—bigland, big leases, big machines. Big debt.Fewer Jobsfor MontanansThe railroads also becamemore mechanized (withmachines doing work previously done by people) andemployed fewer people. Inthe 1960s railroads began—JUDY BLUNT, WHO GREW UP ON A PHILLIPS COUNTY RANCH IN THE 1960Sto lose business to the interstate trucking industry.Traffic shifted away from railroads. More people traveled by car. Firstrailroads decreased passenger and freight service. Then they stoppedrunning branch lines to small towns.In 1970 the Great Northern, the Northern Pacific, and the Chicago,Burlington and Quincy railroads merged (combined) into one company. A few years later the Milwaukee Road shut down. The railroadsthat had once dominated Montana’s transportation began to fade.FIGURE 20.9: American Indians andThe decline of the railroads had a double impact on Montana’s econmigrant workers who used to travelacross the state to work at harvest timeomy. Thousands of well-paid railroad workers in small towns across thefound they could not compete with large,state lost their jobs. And many towns that the new interstates did notefficient machines like these combines,reach lost their major transportation service.photographed in the 1960s near Helena.”Moving from Farm to Town,from East to WestAgriculture became more mechanized, too.Larger machinery meant fewer people couldoperate larger farms and ranches. Big operationsbought up their smaller neighbors. The averagefarm grew larger, but fewer families made theirliving off the land.Over time more rural Montanans moved tothe cities. Billings, Missoula, Bozeman, and GreatFalls expanded rapidly. By 1950 Great Falls—notButte—was Montana’s biggest city. The large,spread-out eastern counties lost many of theirpeople—and remain lightly populated today.Meanwhile, more Montanans moved awayto seek better opportunities elsewhere. Theyfound high-paying jobs in steel plants inUtah, electronics industries in Colorado, andairplane plants in Seattle. Most of the peoplewho moved were young adults just out of highschool or college. This increased the average ageof Montana’s population.404PART 4: THE MODERN MONTANA

Two Communities Grow“Community life is hard, but you know you’llnever have to peel potatoes by yourself.”Two important Montana communitiesdid grow during the postwar years:—SUSIE WALDNER, A MEMBER OF DUNCAN RANCH HUTTERITE COLONY, NEAR HARLOWTONthe Mexican American communitiesof Billings and Laurel, and Montana’s Hutterite colonies.Mexicans began moving to Montana in the 1920s to work in theeastern Montana sugar beet fields and at the Great Western SugarCompany factory in Billings. After World War II, Great Western recruitedeven more Mexicans and Mexican Americans to work in the fields andat the plant. Their labor—along with the work of Northern CheyenneFIGURE 20.10: Sugar beet productionlaborers—helped turn Great Western into the largest sugar manufacturerdepended on migrant workers fromin the United States.Mexico like this young boy, photographed in the lower YellowstoneMexican Americans often faced racism and segregation. They had toValley. All family members joined insit in separate sections in movie theaters and sometimes at school. Somethe backbreaking labor of thinning,cultivating, and harvesting sugar beets.restaurants refused to serve them. Yet Montana’s Mexican Americancommunities grew and steadily fought forsocial change and equal rights.In contrast, Montana’s Hutteritespreferred to separate themselves from mainstream (majority) society. Hutterites aremembers of a religious community formedin Europe in the 1500s. They share all theirresources, live simply, and center their liveson work and church.Hutterites moved to the American Plainsin the 1870s. They refused to fight in WorldWar I because their religion forbids goingto war. Other Americans treated Hutteritesbadly for these beliefs, driving many of themnorth into Alberta, Canada. In 1942 Albertapassed a law prohibiting Hutterites from buying more land. So several Hutterite coloniesmoved into Montana. By 2007 the Hutteriteshad built more than 40 colonies here.Hutterites sometimes face intolerancebecause they live much differently thanother Americans do. As Paul Hofer of theGolden Valley Colony (near Ryegate) said,“It’s a very, very simple life compared to theoutside world. We try to stay away fromit all and stay private as much as we can.”Yet Montana’s Hutterite colonies welcomevisitors and commonly cooperate withtheir neighbors on irrigation projects andland issues.20 — BUILDING A NEW MONTANA405

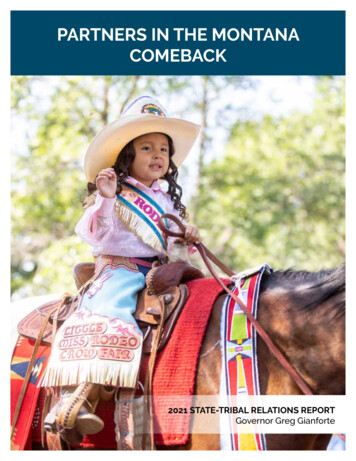

A New U.S. Indian PolicyLife changed on Indian reservations in the 1950s and 1960s.American Indians bought cars and farm machinery. Battery-poweredradios and televisions connected Indian households with mainstreamsociety. But while America boomed, many Indian reservations remainedin poverty.Most Indian military veterans could not take advantage of the GI Billbecause banks did not lend money to build houses on reservations. FewIndians left the reservations to go to college—some colleges did not evenaccept Indians. So the government encouraged Indian people to moveto towns and cities.Some government leaders decided that the problem was the reservation system. They thought it would be better to dissolve Indianreservations (land reserved by tribes for their own use) and encourageIndian people to move to booming towns and cities where they couldget high-paying jobs. As a result Congress changed its policy towardAmerican Indians once again.We have already learned that throughout U.S. history the governmenthas shifted between two completely different policies toward AmericanIndians. One acknowledges Indian tribes as sovereign (independentand self-governing) nations inhabiting their own lands. Under thisapproach the U.S. government made treaties (agreements betweengovernments) with Indian tribes (see Chapter 7).The other approach, which is quite the opposite, sees AmericanIndians as an ethnic group within the U.S. population. Under thisapproach the government periodically has tried to dissolve Indian tribesand to assimilate (absorb) Indian people into mainstream society. TheDawes Act of 1887 was one example of this policy (see Chapter 11).In the 1930s the government returned some powers of self-governmentto tribes and tried to encourage tribal cultures to strengthen (see Chapter 18).In 1953 the government changed its policyHow can we plan our future when the again. Congress decided to end, or terminate,Indian Bureau threatens to wipe us out as its special relationship with some Indiana race? It is like trying to cook a meal in tribes. The government called this policyyour tipi when someone is standing out- termination (the end of something).The government selected specific tribesside trying to burn the tipi down.to terminate. The plan was to withdraw—EARL OLD PERSON, BLACKFEET TRIBAL CHAIRMAN AND CHIEFfederal support from these tribes, abolishtheir tribal governments, sell offI think of the Indian people who have been on tribal lands, and end all treaty(tribal rights established byrelocation and have come back home. I think rightstreaty). In Montana, Congress tar. . . perhaps you come back with more courage, geted the tribes on the Blackfeet,and more determined to make things better.Flathead, Fort Belknap, and FortPeck Reservations for termination.—CAROL JUNEAU, MANDAN-HIDATSA STATE SENATOR FROM THE BLACKFEET RESERVATION““406””PART 4: THE MODERN MONTANA

Indian tribes everywhere resisted termination. They were trying tobuild an economic future. They did not want tribal lands sold off, theirtribal identity destroyed, and their community ties broken.Tribal leaders on the Flathead Reservation organized a steadyprotest and finally convinced Montana’s U.S. senators James E. Murrayand Mike Mansfield to work hard on their behalf. While 61 tribes nationwide were terminated, Montana’s tribes fought successfully to survive.The government did not terminate any Montana tribes. But it didshut down reservation schools, medical clinics, and other services. After200 years of shifting federal policy, American Indians once again had tofight for the right to maintain their tribal identity.Relocation: Indians Were Paid to Move AwayAt the same time, the Bureau of Indian Affairs paid for 100,000 AmericanIndians to relocate (move) from their reservations, where there wereno jobs, to cities where there were jobs. Many of Montana’s Indiansleft their reservations for Butte,Great Falls, and Billings. Othersmoved to cities like Chicagoand Los Angeles.The relocation programhad one unexpected result:it brought many youngIndians of all tribes togetherin American cities duringthe 1960s. Social and politicalchanges were sweeping thenation. Instead of disappearing into mainstream society,Indian people of all tribesbanded together. As Blackfeeteducator Stan Juneau said,“We almost became anurban tribe.” Instead ofdiscarding Indian cultures,American Indians organizedto strengthen them.The termination and relocation programs ended in 1968.After that, a series of ref

Korean War 1953 Termination becomes offi cial federal Indian policy 1953 Montana's fi rst television station broadcasts from Butte 1951 1955 Williston Basin oil fi eld discovered in eastern Montana Open-pit mining begins in Butte 1959 Anaconda Company sells its newspapers 1956 Congress passes Federal Highway Act