Transcription

ISSN 1744-3180Summer 2021Series 3, no. 49News from the ChairWelcome to the Summer issue of the LIHG newsletter. While we wait for news on when in-person eventsmay again be possible, this issue contains two features which encourage us to reflect on the success of ouronline events. Having regaled us with an excellent talk at our last work-in-progress session, Alistair Blackhas contributed an article that further explores the depiction of librarianship in post-war cinema. Eleanor Kellyhas provided a write-up of Alice Ford-Smith’s virtual “Lonely hearts ” walk, which was a wonderful way tospend a virtual Valentine’s day evening.This issue also has us looking forward to our annual conference on Saturday 3rd July, again taking placeonline. Please consider joining us if you can. Many thanks in advance to all our speakers, and to Angela Plattfor putting together such an excellent programme.Finally, this issue also throws a spotlight on other ways in which LIHG supports research into Library andInformation history – the essay prize, and the James Ollé award. Please share these with others who maybe interested.Jill DyeChair, CILIP Library & Information History GroupTable of ContentsWhat can the film Only Two Can Play (1962) tell us about post-war public librarianship in Britain? . 2Library History Essay Award 2021 . 5Lonely hearts, wedding bells and illicit pleasures: a far from sentimental journey into how London loved in print . 6James Ollé Awards . 7Power and Resistance in Library History: . 8CILIP LIHG Conference 2021 . 8Events . 9SIG Library History Oral Histories Project . 9Publications. 10Author Query . 10Historic Libraries Forum (HFL) statement on cuts to staff and services in libraries with Unique and DistinctiveCollections (UDC) . 11Back Matter . 111

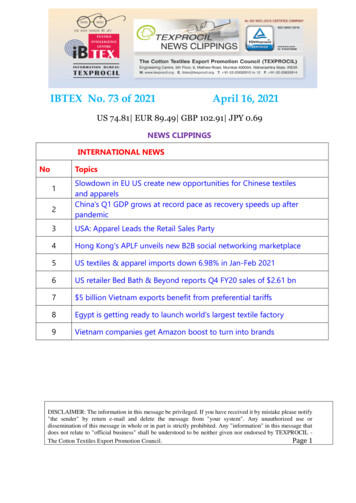

ISSN 1744-3180Summer 2021Series 3, no. 49What can the film Only Two Can Play (1962) tell usabout post-war public librarianship in Britain?Figure 1. Peter Sellers and Mai Zetterling in a scene from Only Two Can Play (1962). Courtesy ofSTUDIOCANAL.Since roughly the middle of the twentieth century,the development of history as a subject has seena commensurate diversification in the type ofprimary sources investigated and referenced byhistorians. This widening conceptualisation of whatconstitutes a legitimate primary resource hasincluded feature films.1 Treated with appropriatemethodological care, cinematic productions throwlight on the periods in which they were created, richas they are, as the historian Arthur Marwickreminds us, in their potential to not only recordeveryday practices but also reveal contemporary“attitudes, assumptions, mentalities, and values”.2Librarians and the library have been makingappearances in films since the early days ofcinema. However, the vast majority of roles2

ISSN 1744-3180Summer 2021allocated to what Tevis and Tevis call “reel”librarians or libraries have been of the “backdrop”or “cameo” kind.3 Classic and much citedexamples of films that display such roles includeIt’s a Wonderful Life (1947), Breakfast Club (1985),and The Day After Tomorrow (2004). Televisionproductions that fall into this category include Buffythe Vampire Slayer (seven seasons, 1997-2002)and The Librarian (3 films, 2004-08), neither ofwhich are primarily about the institution of thelibrary or the occupation of the librarian. Listings ofsuch productions are many,4 and in 2007 thecontents of such lists were brought to life in thedocumentary The Hollywood Librarian.5 Bycontrast, very few films have featured the librarianas a main protagonist or librarianship as a majordriver of the plot. The very few films that fall intothis category include Storm Center (1956), DeskSet (1957), Party Girl (1995), The Public (2018),and, if a slight stretching of the parameters isallowed, The Music Man (1962).You don’t need to be a film buff to know thatthese five productions were set in the UnitedStates. The only film set in a British context thatcan be identified as belonging to the category inquestion is Only Two Can Play (1962).6 Directedby Sidney Gilliat and a success at the British boxoffice, Only Two Can Play was a production ofBritish Lion Films, a cornerstone of the post-warBritish film industry. British Lion Films’ catalogueincluded such famous films as The Third Man(1949) and Lord of the Flies (1963). Among itscomedy productions were I’m All Right Jack (1959)and Heavens Above! (1963). Both these filmsstarred Peter Sellers, who also fronted Only TwoCan Play. It too was a comedy but, like the othertwo, not one of the “laugh out loud” kind.In Only Two Can Play, Sellers plays thecharacter John Lewis, a librarian in the fictionalAberdarcy Public Library. The town of Aberdarcywas based on Swansea, where Kingsley Amis, theauthor of the 1955 novel That Uncertain Feeling(1955) that gave rise to the film, lived between1949 and 1961, working as a lecturer at theuniversity. Many of the exterior scenes in the filmwere shot in Swansea.In the scenes that precede the openingcredits, John, our leading protagonist, is shown tohave a wandering eye for the opposite sex. In thescenes that immediately follow these credits, hiscredentials as a lothario are firmly established.One morning, the character of Elizabeth GruffyddWilliams, played by the Swedish actress MaiZetterling, comes into the library. Elizabeth, aglamorous local socialite, is involved with a localSeries 3, no. 49amateur dramatics group and she is looking forbooks on medieval Welsh dress to lendauthenticity to one of the group’s upcomingproductions. Unable to satisfy her enquiry, a youngfemale library assistant calls John, her seniorcolleague, over to help. Flirting ensues and aromance between the two is born (Figure 1).However, it is a romance doomed to failure. Johnand Elizabeth never manage to get into bed. Eachplanned tryst in the film ends in comic disaster and“failed consummation”, portrayed in scenes thatmake the most of Seller’s slapstick skills set.The romance between the two is complicatedby John’s decision to apply for the vacant post ofsub-librarian (“deputy librarian” in other librarysettings). Elizabeth is married to a colourless,muted businessman, Vernon. He is a localcouncillor and serves on the council’s publiclibraries committee. Elizabeth is thus able to pullstrings, to John’s advantage. Although uncertainabout applying, being disillusioned with themonotony of work and an unfulfilling career, Johnis ultimately persuaded to do so by his longsuffering wife, Jean (played by Virginia Maskell), inthe hope that the family can earn the extra moneyneeded to escape their dreary surroundings andlives. John and Jean have two young children.They live in three cramped and grubby rooms onthe top floor of a Victorian terraced villa convertedinto flats. They share a bathroom with other flatsand have to put up with the intrusive gaze of aninterfering landlady. So, we see that the Lewisfamily is not poor, but they are hardly “well off”.“Hard up” would be a fair description of theirsituation. At the end of the film we find that John,having turned down the job of sub-librarian, hasopted instead for a peaceful life on a mobile library,visiting country villages where, away from city lifeand the drudgery of life in the central library, thetemptations offered by women other than his wifecan be presumably be resisted.John’s sexual and career frustrations, playedout in a framework of light comedy, drive thestoryline forward. What gives the film anundoubted impact, however, is that its centralcharacter is a librarian. Audiences at the timewould have largely expected a librarian to besexually conservative. They would also expect alibrarian to enjoy a comfortable standard of living.Even if they were not comfortable in this regard,the expectation would have been that they werecheerfully engaged in their vocation due to acertain intellectual motivation. The fact that Johndoes not fit this formula lends the film dramaticpower.3

ISSN 1744-3180Summer 2021Such an analysis suggests the idea that thefilm, though fundamentally a form of entertainment,contains hidden meanings of interest to thehistorian. Cultural products both portray and betraymeaning.7 Regarding these, we can ally revealed by the film’s “authors”, byits screenwriter, producers and director? The gapbetween “authorial intent” and what is “unwittingly”conveyed is critical to understanding what the filmultimately means.For example, if one takes the enduringquestion of the image of the librarian, about whichmuch has been written,8 what the film portrays isarguably an anti-stereotype. Despite someepisodes of foolishness and clumsy ineptness,John comes across as socially and sexuallyconfident and, at times, even suave. There arenumerous hints in the film as to his promiscuity. Heis a seducer and a charmer. John is not afraid ofsocial engagement. He appears comfortableamong party people and, as theatre critic for a localpaper, he is civically invested. It might beconvincingly argued that the anti-stereotype wasrequired to deliver comic and dramatic effect. Butin choosing the anti-stereotype for this reason, thefilm makers in fact betray their awareness of astrong stereotypical image of the librariancirculating in society—the librarian as reserved,reclusive, serious-minded, other-worldly, andmonk-like, traits to which John returns at the endof the film when he openly surrenders hisphilandering.A further example of the “portrayal-betrayal”concept can be seen in the film’s depiction of theAberdarcy Public Library building. In terms of itsdesign, what is portrayed is a building in theEdwardian baroque style. It could be argued thatthe film makers’ choice of building and style wassub-conscious, because they thought that’s what alibrary should look like. In other words, theyinstinctively bought into the notion of “libraryness”,which in terms of physical appearance demandedthe deployment of historical references, reserving knowledge through the ages. Theimpression we get of the library is that we are in adusty place where culture and books are in a stateof decay or, at best, in a time warp. By the early1960s, there certainly existed a selection oflibraries fashioned in modernist styles, or even in astripped classical mode, from which to make aselection. It is not as if the film makers werecommitted in some way to depict the central libraryin Swansea—because they were not! In fact, it wasSeries 3, no. 49the art gallery over the road from the Victorian,Italianate Swansea Central Library that was usedto represent Aberdarcy Public Library.In other ways, the use of a building around halfa century old, furnished with utility shelving andadorned with classical busts, is entirelytransparent. It symbolises a library world stuck inthe past, yet to be touched by the promised andplanned post-war revival in public libraryprovision.9 More mundanely, the film offers awindow into the public library’s past that faithfullyreflects reality. On display in the film, even if onlyfleetingly, is the Browne book issue system; theinter-library loan service; book banning; the librarystaff room; and a mobile library of the time.Audiences were also given an insight into staffingstructures (the difference between libraryassistant, assistant librarian, sub-librarian, andchief librarian); salary levels (John’s promotionwould give him an extra 150 a year); professionaltraining (John tells us he has a degree and haspassed other exams); and governance (theinterview for the sub-librarian post by the librarycommittee occupies a significant segment of thefilm). All these serve as prompts to the enquiringstudent of post-war public library service. Indeed,it is worth noting at this point that such “facts” ofpublic library history both intrigued and informedthe students of my “Libraries in Film” module,prompting them to dig down into the importantminutiae of everyday library life.A further faithfully constructed reality in thefilm is the debate about popular culture and the“right” balance that was sought at the time in thecomplexion of the book stock and, it followed, ininstitutional philosophy and purpose. This “culturewars” theme runs as a major thread throughout thefilm. A notable theme is the library’s delivery ofboth high-brow non-fiction and light (includingromantic) fiction, and the tension between the two.There is also coverage of the social width of thelibrary’s readership, from the working classes andthe morally suspect social outsider, to theintellectual and the socially connected and well-todo.Such realities (although maybe not exactly thesame ones) about the history of the post-war publiclibrary, are also visible in Amis’ That UncertainFeeling, the genesis of the film. What the film andthe book don’t share, however, is commentary, orobservations, on John’s political beliefs. In thebook, John exhibits a radical streak. Despite hiscollege education and professional status, he isdistinctly hostile to Welsh middle-class culture, notleast because of its tendency to embrace English4

ISSN 1744-3180Summer 2021traits. In the film, by contrast, John’s class politicsare sanitised. This is not surprising, given the needfor the film to attract a mass audience.Interestingly, however, the absence of politics inthe film corresponded to the prevailing massifiedapproach to library provision. The dominantphilosophy in public librarianship and public librarypolicy after the war was to build, once austerity hadfaded, a significantly expanded service, reachingsections of the population previously “unserved”.Critically, this was to be achieved on a universal,“one size fits all” basis. Not until the 1970s, with theorigins of community librarianship, did ideas abouta redistributive library service—one that prioritizedthe socially excluded and alternative and marginalcultures—gain traction.10Alistair BlackProfessor EmeritusUniversity of Illinois Urbana-ChampaignAlistair Black is the author of the following books: ANew History of the English Public Library (1996); ThePublic Library in Britain 1914-2000 (2000); andLibraries of Light: British Public Library Design in theLong 1960s (2017). He is co-author of UnderstandingCommunity Librarianship (1997); The EarlyInformation Society in Britain, 1900-1960 (2007); andBooks, Buildings and Social Engineering (2009), asocio-architectural history of early public libraries inBritain. With Peter Hoare, he edited Volume 3(covering 1850-2000) of the Cambridge History ofLibraries in Britain and Ireland (2006). He was chairof the Library History Group of the American LibraryAssociation (1992-99) and of the IFLA Section onLibrary History (2003-07). He also served as editor ofSeries 3, no. 49the international journal Library History (2004-08);North American editor of Library and InformationHistory (2009-13); and Library Trends coeditor(2009-13) and editor (2013-16). Presently, hisresearch focuses on the history of corporate librariesand staff magazines and the design of public librariesin the 1960s.ReferencesV.R. Schwartz, Film and History, in J. Donald & M. Renoy(eds.), The Sage handbook of film studies, London: Sage, 2008,pp. 199-215.2 A. Marwick, The new nature of history: knowledge, evidence,language, London: Red Globe Press, 2001, p. 168.3 R. Tevis and B. Tevis, The image of librarians in cinema, 19171999, Jefferson, North Carolina: MacFarland, 2005. See, also, L.Marcus, The library in film, in A. Crawford (ed.), The meaning ofthe library: a cultural history, Princeton, New Jersey: PrincetonUniversity Press, 2015, pp. 199-219.4 For example, E. Smart and S. Currant, The 10 best librarianson screen, British Film Institute, 2019, available ists/10-bestlibrarians-screen [accessed 2.6.21].5 The Hollywood librarian: a look at librarians through film,Overdue Productions, 2007.6 I first became interested in Only Two Can Play in the context ofthe methodology of history when I devised and taught a courseentitled ‘Libraries in Film’ in the School of Information Sciences,University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2013.7 L. Back, Portrayal and betrayal: Bourdieu, photography andsociological life, The Sociological Review, 57(3) (2009), pp. 47190.8 For example, A. White, Not your ordinary librarian: debunkingthe popular perception of librarians, Oxford: Chandos, 2012.Also, see Reference Librarian, 37(78) (2003) for a special issueon the subject.9 A. Black, The public library in Britain, 1914-2000, London: TheBritish Library, 2000, pp. 111-40; T. Kelly, A history of the publiclibrary in Great Britain, 1845-1975, London: Library Association,1977, pp. 327-425.10 A. Black and D. Muddiman, Understanding communitylibrarianship, Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997.1Library History Essay Award 2021The Library History Essay Award is an annual prize for thebest article or chapter on library history published in, orpertaining to, the British Isles, within the previous calendaryear.** Introduced in 1996, the award is organised andsponsored by the LIHG and aims to support the publication ofresearch into library history in the British Isles. The prize is 350.Submissions should contain original historical research andbe based on original source materials if possible. Evidence ofmethodological and historiographical innovation is particularlywelcome.Authors may put themselves forward for the prize but maymake only one submission per year. Any member of CILIPmay also nominate a published essay for consideration. Theentries will be identified and judged by a panel of three: Chair of the LIHGAwards Manager of the LIHGExternal Assessor at the invitation of the LIHGCommitteeNominations (and any queries relating to the award) should besent to the Group's Awards Manager:Dr Dorothy Clayton, Awards Manager, LIHGTel: 0161 826 3883; or 07769658649Email: dorothy.clayton@manchester.ac.uk**2021** Library History Essay AwardDue to Covid-19 and the difficulties experienced byresearchers, libraries, record offices, and publishers, the 2021LIHG Essay Award will be made to the author whose writingwas published in 2019 or 2020.Deadline for submitting articles is 30 September 2021.5

ISSN 1744-3180Summer 2021Series 3, no. 49Lonely hearts, wedding bells and illicit pleasures:a far from sentimental journey into how London loved in printThe New Swell's Night Guide, ca. 1847 (British Library)Public domain image from: Booksellers) virtual tour on Valentine’s Day 2021gave fascinating insights into how love, passion,and marriage were found, nurtured, and exploitedin London. Consisting of eleven stops, thisthoroughly enjoyable tour offered the chance toengage with London’s printing heritage from thecomfort of your own home. Whilst the Covidpandemic might have prevented an in-person tour,the lack of the usual sights and sounds of a tourdid not prevent you from being fully transported tothe highs and lows of love in London. Alice’s vividdescriptions and helpful map references fullycharacterised each stop.Beginning in the heart of London’s literarylandscape, Bloomsbury, our first stop was toSenate House where we learnt how Sir JohnBetjeman’s encounter with Joan Hunter Dunn in1940 inspired his poem "A Subaltern's Love-song",and a friendship that lasted over forty years. Alicealso highlighted Senate House Library’s morerecent contribution to the discourse on literary love,the 2018 exhibition ‘Queer Between the Covers’,which showcased over 250 years of queerliterature. A short virtual walk south-east took us toBloomsbury Square and back to 1742, where weheard how publications helped younger brothers tonavigate the marriage market. A master-key to therich ladies treasury, or, The widower andbatchelor’s directory by a Younger Brother (1742)assisted younger brothers who, unlike the eldestson, would not inherit the family’s fortunes infinding potential marriages to ladies with reputedfortunes. Our third stop took us to the BritishMuseum on Great Russell Street to consider thesubject of obscenity. The Private Case, formed inthe 1850s and now housed in the British Library,contains material thought to be too indecent for themain collection. The inclusion and exclusion ofcertain texts provides a fascinating insight into thehistoric attitudes towards erotic material.6

ISSN 1744-3180Summer 2021The theme of illicit material continued throughoutthe next three stops. The fourth stop at Drury Lanehighlighted Harris's List of Covent Garden Ladies,an annual directory of “ladies of pleasure” whichwas published from the middle to the end of theeighteenth century. At the next stop, theMagistrates Court on Bow Street, Alice highlightedJohn Clemand’s Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure(1748). Popularly known as Fanny Hill this wasthought to be one of the most banned andprosecuted books. Censorship of this textcontinued into the 1960s when Mayflower Bookspublished an uncensored paperback edition in1963, which was later banned under the ObscenePublications Act 1959. The Strand was stop six,and continued the theme of publications onpromiscuous women, this time detailing The NewSwell's Night Guide, early nineteenth centuryguidebooks highlighting the various venues wheresex workers could be found.Alice’s next step brought us back to the twentiethcentury where, further along the Strand, shehighlighted the publication of the London City GayMap in 1982 by Spartacus International, thought tobe one of the first times a mainstream publisher (inthis case Bartholomew and Sons) permitted theircartography to be used in this way.Stop eight on Rose Street, Covent Garden focusedon dubious eighteenth-century bookseller andpublisher Edward Curll, who became so notoriousSeries 3, no. 49for his indecent publications that “Curlicism” wassynonymous for literary indecency.No Valentine’s day tour would be complete withoutcards, and the ninth stop on Gerrard Street delvedinto the history of Valentine’s Day cards. Unlikeheart-felt, cute, twenty-first century cards, VinegarValentine’s, popular in the nineteenth and earlytwentieth centuries, were sent to ridicule therecipient.The penultimate stop of the walk was ShaftesburyAvenue, and featured Paul Pry’s For YourConvenience: a Learned Dialogue Instructive to allLondoners and London Visitors, first published in1937. In addition to describing the location andstate of public conveniences in London, readingbetween the lines, this book can be considered thefirst Queer city guide.The virtual tour concluded at 84 Charing CrossRoad with the book of the same name. This heartwarming story of the 20 year-long correspondencebetween Helene Hanff, writing from New York, andFrank Doel, manager of Mark & Co. antiquarianbooksellers in Charing Cross finished off thejourney perfectly. Alice’s tour undoubtedlyhighlighted the role that printing has played, bothhistorically and recently, in London’s amorousliterary heritage.Eleanor KellyAssistant Librarian, St Hilda’s College LibraryJames Ollé AwardsJames G. Ollé (1916-2001) was an active teacher and distinguished writer in the field of library history; the Library andInformation History Group has offered awards in his memory since 2002 with the intention of encouraging a high levelof activity in library and information history.Individuals may apply for an award of up to 500 each year for expenses relating to a library history project. Examplesof what an Award might be used to fund include: Access to primary resources, e.g. travel, procurement of scans/photographs, one year’s subscription to databasesor credits for sources such as birth/marriage/death records. Procurement of secondary sources e.g. key reference texts, inter-library loan fees.Please note that the award is not intended to support conference attendance. Anyone with a keen interest in Libraryand/or Information History is encouraged to apply, regardless of academic affiliation, but recipients must be membersof the CILIP Library and Information History Group (already, or willing to join upon receipt of an award).James Ollé Award recipients will be asked to write a report (maximum 1000 words) of the work undertaken for inclusionin the LIHG's Newsletter, and may be invited to present a short paper at an LIHG conference or meeting, such as theAGM. To apply for the award, please send a short CV, statement of plans and draft budget to the LIHG’s AwardsManager. Applications may be made throughout the year. Potential applicants are welcome contact the AwardsManager with any queries about the award, or to request sample statements/budgets to help with their application.Dr Dorothy Clayton, Awards Manager, LIHGTel: 0161 826 3883; or 07769658649; Email: dorothy.clayton@manchester.ac.uk7

ISSN 1744-3180Summer 2021Series 3, no. 49Power and Resistance in Library History:CILIP LIHG Conference 2021This event will take place online via Zoom on Saturday 3 July 2021, 10am – 3.30pm.Joining information will be sent to registered participants the day before the event.Professor Alistair BlackPower Resistance Negotiation: A Functional Equation for the History of Libraries?Daisy StaffordAccess for all: Tensions Between Reform, Recreation, and Exclusion in the History of PublicLibraries, 1850-2021.Dr Colin HigginsThe Revolutionary in Disguise: Lenin and Mao as Library Workers.Victoria StevensKnowledge is Power: A Case Study of the Rise and Fall of a Kent County House Library in itsWider Social Context.Dr Max SkjönsbergReading Politics in Eighteenth-Century Subscription Libraries.Professor Mark TowseySubscription Libraries, Empire, and the Wider World: Participation and Resistance.Dr Sophie JonesSocial Libraries and the Formation of Political Loyalties during the American Revolution.Register here: kets-1565188651398

ISSN 1744-3180Summer 2021EventsLibraries Without Borders10-12 June mLIHG Chair and Library & Information HistoryEditor Jill Dye will be speaking at a panel on Friday11 June at 2pm Eastern US time (7pm in the UK):Getting Your Historical Research Published: Q&Awith Journal 51493131History of Libraries1 June 2021, fication in the 1789 Catalogue of the LibraryCompany of PhiladelphiaJames N. GreenThis talk is about the Library Company ofPhiladelphia’s 1789 printed catalogue and itsinnovative subject arrangement, which wasderived from d’Alembert’s classification of humanknowledge according to the three fundamentalfaculties of the mind: Memory, Reason, andImagination. The catalogue inspired an enigmaticallegorical painting that the Library Companycommissioned in 1792, which has startled andconfused generations of gue-library-company-philadelphiaBloomsbury’s Lost Libraries23 June 2021, 6-7pmThis virtual walk will carry you back throughBloomsbury’s history to long-forgotten libraries,readers, librarians and collectors. Alice Ford-Smith(Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers) will revealsome of the links between the area’s past andpresent book collections and the tales ofenterprise, obsession, and destruction that areoften behind -libraries-walk-through-someSeries 3, no. 49SIG Library History Oral Histories ProjectAs outlined in its Action Plans from 2019 the SIGLibrary History has embarked on what some mightthink are a very ambitious set of projects on the oralhistories of our librarians past and present. As theproject develops a number of streams revealthemselves and those we can report activity on are:Recording the oral histories of IFLA’s PastPresidents,SecretariesGeneralandPersonalities. The goal of these three aspects is toget as many recordings as possible done for IFLA’scentenary in 2027 and through negotiation andsupport from IFLA the projects have nowcommenced. And how fortunate the SIG is to have aconvenor for each component,

family is not poor, but they are hardly "well off". "Hard up" would be a fair description of their situation. At the end of the film we find that John, having turned down the job of sub-librarian, has opted instead for a peaceful life on a mobile library, visiting country villages where, away from city life