Transcription

CRD’s original guidance for undertaking systematic reviews was firstpublished in 1996 and revised in 2001. The guidance is widely used,both nationally and internationally.The purpose of this third updated and expanded edition remainsto provide practical guidance for undertaking systematic reviewsevaluating the effects of health interventions. It presents the differentstages of the process and incorporates issues specific to reviews ofdiagnostic and prognostic tests, public health interventions, adverseeffects and economic evaluations. Recognising that health caredecision-making often involves complex questions that go beyond‘does it work’, the guidance also includes information relating to howand why an intervention works.CRD is part of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) andis a department of the University of York, UK. CRD was establishedin 1994 and undertakes systematic reviews evaluating the effects ofinterventions used in health and social care.ISBN 978-1-900991-19-3LESAMP9 781900 991193Centre for Reviews and DisseminationUniversity of YorkHeslingtonYork YO10 5DDUnited Kingdomwww.york.ac.uk/inst/crd

Systematic ReviewsCRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews inhealth careCRD Systematic Reviews.indd 2838/1/09 09:29:56

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, 2008Published by CRD, University of YorkJanuary 2009ISBN 978-1-900640-47-3This publication presents independent guidance produced by the Centre for Reviews andDissemination (CRD). The views expressed in this publication are those of CRD and notnecessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.All rights reserved. Reproduction of this book by photocopying or electronic means fornon-commercial purposes is permitted. Otherwise, no part of this book may be reproduced,adapted, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical,photocopying, or otherwise without the prior written permission of CRD.Cover design by yo-yo.uk.comPrepared and printed by:York Publishing Services Ltd64 Hallfield RoadLayerthorpeYork YO31 7ZQTel: 01904 431213Website: www.yps-publishing.co.ukCRD Systematic Reviews.indd 2848/1/09 09:29:56

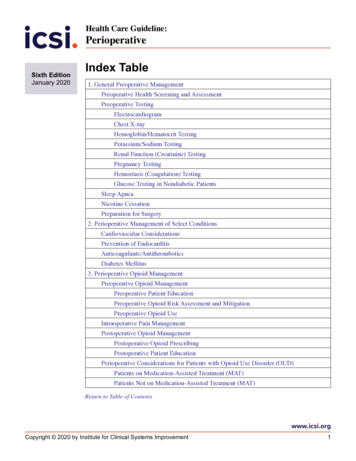

ContentsPrefacevAcknowledgementsixChapter 1Core principles and methods for conducting a systematicreview of health interventionsChapter 2Systematic reviews of clinical testsChapter 3Systematic reviews of public health interventions157Chapter 4Systematic reviews of adverse effects177Chapter 5Systematic reviews of economic evaluations199Chapter 6Incorporating qualitative evidence in or alongsideeffectiveness reviews2191109APPENDICES:Appendix 1 Other review approachesAppendix 2 Example search strategy to identify studies fromelectronic databasesAppendix 3 Documenting the search processAppendix 4 Searching for adverse 7CRD Systematic Reviews.indd 2852398/1/09 09:29:56

CRD Systematic Reviews.indd 2868/1/09 09:29:56

PREFACEThis third edition of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidance forundertaking systematic reviews builds on previous editions published in 1996 and 2001.Our guidance continues to be recommended as a source of good practice by agenciessuch as the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (NIHRHTA) programme, and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE),and has been used widely both nationally and internationally. Our aim is to promotehigh standards in commissioning and conduct, by providing practical guidance forundertaking systematic reviews evaluating the effects of health interventions.WHY SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS ARE NEEDEDHealth care decisions for individual patients and for public policy should be informedby the best available research evidence. Practitioners and decision-makers areencouraged to make use of the latest research and information about best practice, andto ensure that decisions are demonstrably rooted in this knowledge.1, 2 However, thiscan be difficult given the large amounts of information generated by individual studieswhich may be biased, methodologically flawed, time and context dependent, and canbe misinterpreted and misrepresented.3 Furthermore, individual studies can reachconflicting conclusions. This disparity may be because of biases or differences in the waythe studies were designed or conducted, or simply due to the play of chance. In suchsituations, it is not always clear which results are the most reliable, or which should beused as the basis for practice and policy decisions.4Systematic reviews aim to identify, evaluate and summarise the findings of all relevantindividual studies, thereby making the available evidence more accessible to decisionmakers. When appropriate, combining the results of several studies gives a morereliable and precise estimate of an intervention’s effectiveness than one study alone.5-8Systematic reviews adhere to a strict scientific design based on explicit, pre-specifiedand reproducible methods. Because of this, when carried out well, they provide reliableestimates about the effects of interventions so that conclusions are defensible. As wellas setting out what we know about a particular intervention, systematic reviews canalso demonstrate where knowledge is lacking.4, 9 This can then be used to guide futureresearch.10WHAT IS COVERED IN THE GUIDANCEThe methods and steps necessary to conduct a systematic review are presented in acore chapter (Chapter 1). Additional issues specific to reviews in more specialised topicareas, such as clinical tests (diagnostic, screening and prognostic), and public healthare addressed in separate, complementary chapters (Chapters 2-3). We also considerquestions relating to harm (Chapter 4) costs (Chapter 5) and how and why interventionswork (Chapter 6).vCRD Systematic Reviews.indd 2878/1/09 09:29:57

Systematic ReviewsThis guide focuses on the methods relating to use of aggregate study level data.Although discussed briefly in relevant sections, individual patient data (IPD) metaanalysis, which is a specific method of systematic review, is not described in detail. Thebasic principles are outlined in Appendix 1 and more detailed guidance can be foundin the Cochrane Handbook11 and specialist texts.12, 13 Similarly, other forms of evidencesynthesis including prospective meta-analysis, reviews of reviews, and scoping reviewsare beyond the scope of this guidance but are described briefly in Appendix 1.WHO SHOULD USE THIS GUIDEThe guidance has been written for those with an understanding of health research butwho are new to systematic reviews; those with some experience but who want to learnmore; and for commissioners. We hope that experienced systematic reviewers willalso find this guidance of value; for example when planning a review in an area that isunfamiliar or with an expanded scope. This guidance might also be useful to those whoneed to evaluate the quality of systematic reviews, including, for example, anyone withresponsibility for implementing systematic review findings.Given the purpose of the guidance, the audience it is designed for, and the aim toremain concise, it has been necessary to strike a balance between the wide scopecovered and the level of detail and discussion included. In addition to providingreferences to support statements and discussions, recommended reading of morespecialist works such as the Cochrane Handbook,14 Systematic Reviews in the SocialSciences,4 and Systematic Reviews in Health Care15 have been given throughout thetext.HOW TO USE THIS GUIDEThe core methods for carrying out any systematic review are given in Chapter 1 whichcan be read from start to finish as an introduction to the review process, followed stepby step while undertaking a review, or specific sections can be referred to individually.In view of this, and the sometimes iterative nature of the review process, occasionalrepetition and cross referencing between sections has been necessary.Chapters 2-5 provide supplementary information relevant to conducting reviewsin more specialised topic areas. To minimize repetition, they simply highlight thedifferences or additional considerations pertinent to their speciality and should be usedin conjunction with the core principles set out in Chapter 1. Chapter 6 provides guidanceon the identification, assessment and synthesis of qualitative studies to help explain,interpret and implement the findings from effectiveness reviews. This reflects thegrowing recognition of the contribution that qualitative research can make to reviews ofeffectiveness.viCRD Systematic Reviews.indd 2888/1/09 09:29:57

PrefaceFor the purposes of space and readability:The term ‘review’ is used throughout this guidance and should be taken as a short formfor ‘systematic review’, except where it is explicitly stated that non-systematic reviewsare being discussed.‘Review question’ is used in the singular even though frequently there may be morethan one question or objective set. The same process applies to each and everyquestion.A glossary of terms has been provided to ensure a clear understanding of the use ofthose terms in the context of this guidance and to facilitate ease of reference for thereader.REFERENCES1. Bullock H, Mountford J, Stanley R. Better policy-making. London: Centre forManagement and Policy Studies; 2001.2. Strategic Policy Making Team. Professional policy making for the twenty first century.London: Cabinet Office; 1999.3. Wilson P, Petticrew M, and on behalf of the Medical Research Council’s PopulationHealth Sciences Research Network knowledge transfer project team. Why promote thefindings of single research studies? BMJ 2008;336:722.4. Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide.Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2006.5. Oxman AD. Meta-statistics: help or hindrance? ACP J Club 1993;118:A-13.6. L’Abbe KA, Detsky AS, O’Rourke K. Meta-analysis in clinical research. Ann Intern Med1987;107:224-33.7. Thacker SB. Meta-analysis: a quantitative approach to research integration. JAMA1988;259:1685-9.8. Sacks HS, Berrier J, Reitman D, Acona-Berk VA, Chalmers TC. Meta-analysis ofrandomized controlled trials. N Engl J Med 1987;316:450-5.9. Petticrew M. Why certain systematic reviews reach uncertain conclusions. BMJ2003;326:756-8.10. Brown P, Brunnhuber K, Chalkidou K, Chalmers I, Clarke C, Fenton M, et al. How toformulate research recommendations. BMJ 2006;333:804-6.11. Stewart LA, Tierney JF, Clarke M. Chapter 19: Reviews of individual patient data.In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews ofinterventions. Version 5.0.0 (updated February 2008): The Cochrane Collaboration;2008. Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.org.viiCRD Systematic Reviews.indd 2898/1/09 09:29:57

Systematic Reviews12. Stewart LA, Clarke MJ. Practical methodology of meta-analyses (overviews) usingupdated individual patient data. Cochrane Working Group. Stat Med 1995;14:2057-79.13. Stewart LA, Tierney JF. To IPD or not to IPD? Advantages and disadvantages ofsystematic reviews using individual patient data. Eval Health Prof 2002;25:76-97.14. Higgins JPT, Green S, (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews ofinterventions. Version 5.0.0 [updated February 2008]: The Cochrane Collaboration;2008. Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.org15. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG. Systematic reviews in health care: metaanalysis in context. 2nd ed. London: BMJ Books; 2001.viiiCRD Systematic Reviews.indd 2908/1/09 09:29:57

AcknowledgementsThis guidance has been produced as a collaborative effort by the following staff atCRD, building on the work of the original writers of CRD Report 4 (Editions 1 & 2).Jo Akers, Raquel Aguiar-Ibáñez, Ali Baba-Akbari Sari, Susanne Beynon, Alison Booth,Jane Burch, Duncan Chambers, Dawn Craig, Jane Dalton, Steven Duffy,Alison Eastwood, Debra Fayter, Tiago Fonseca, David Fox, Julie Glanville, Su Golder,Susanne Hempel, Kate Light, Catriona McDaid, Gill Norman, Colin Pierce, Bob Phillips,Stephen Rice, Amber Rithalia, Mark Rodgers, Frances Sharp, Amanda Sowden,Lesley Stewart, Christian Stock, Rebecca Trowman, Ros Wade, Marie Westwood,Paul Wilson, Nerys Woolacott, Gill Worthy and Kath Wright.CRD would like to thank Doug Altman, Director of the Centre for Statistics inMedicine and Cancer Research UK Medical Statistics Group, at the University ofOxford, for writing the Prognostics section of Chapter 2, Reviews of clinical tests.CRD is grateful to the following for their peer review comments on draft versions ofvarious chapters of the guidance:Doug Altman, Centre for Statistics in Medicine, University of Oxford.Rebecca Armstrong, Melbourne School of Population Health, University ofMelbourne.Jeffrey Aronson, Department of Primary Health Care, University of Oxford.Deborah Ashby, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, QueenMary, University of London.Andrew Booth, Trent RDSU Information Service at ScHARR Library, University ofSheffield.Patrick Bossuyt, AMC, University of Amsterdam.Nicky Britten, Institute of Health Service Research, Peninsula Medical School,Universities of Exeter and Plymouth.Mike Clarke, UK Cochrane Centre, Oxford.Jon Deeks, Department of Public Health and Epidemiology, University ofBirmingham.Mary Dixon-Woods, Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester.Jodie Doyle, Melbourne School of Population Health, University of Melbourne.Mike Drummond, Centre for Health Economics, University of York.Zoe Garrett, Centre for Health Technology Evaluation, NICE.Ruth Garside, Peninsula Medical School, Universities of Exeter and Plymouth.Julie Hadley, Faculty of Health, Staffordshire University.Roger Harbord, Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol.ixCRD Systematic Reviews.indd 2918/1/09 09:29:57

Systematic ReviewsAngela Harden, EPPI-Centre, University of London.Andrew Herxheimer, UK Cochrane Centre, Oxford.Julian Higgins, MRC Biostatistics Unit, Institute of Public Health, Cambridge.Chris Hyde, ARIF and West Midlands HTA Group, University of Birmingham.Mike Kelly, Centre for Public Health Excellence, NICE.Jos Kleijnen, Kleijnen Systematic Reviews.Carole Lefebvre, UK Cochrane Centre, Oxford.Yoon Loke, School of Medicine, Health Policy and Practice, University of East Anglia.Susan Mallett, Centre for Statistics in Medicine, University of Oxford.Heather McIntosh, Community Health Sciences, University of Edinburgh.Miranda Mugford, School of Medicine Health Policy and Practice, University of EastAnglia.Mark Petticrew, Public and Environmental Health Research Unit, London School ofHygiene and Tropical Medicine.Jennie Popay, Division of Health Research, Lancaster University.Deidre Price, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, University of Oxford.Gerry Richardson, Centre for Health Economics, University of York.Jonathan Sterne, Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol.Jayne Tierney, MRC Clinical Trials Unit, London.Luke Vale, Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen.Liz Waters, Melbourne School of Population Health, University of Melbourne.Penny Whiting, Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol.xCRD Systematic Reviews.indd 2928/1/09 09:29:58

CHAPTER 1CORE PRINCIPLES AND METHODS FOR CONDUCTINGA SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF HEALTH INTERVENTIONS1.1 GETTING STARTED1.1.1 Is a review required?1.1.2 The review team1.1.3 The advisory group33451.2 THE REVIEW PROTOCOL1.2.1 Introduction1.2.2 Key areas to cover in a review protocol1.2.2.1 Background1.2.2.2 Review question and inclusion criteria1.2.2.3 Defining inclusion criteria1.2.2.4 Identifying research evidence1.2.2.5 Study selection1.2.2.6 Data extraction1.2.2.7 Quality assessment1.2.2.8 Data synthesis1.2.2.9 Dissemination1.2.3 Approval of the draft protocol1.2.4 How to deal with protocol amendments during the review666661013131314141414151.3 UNDERTAKING THE REVIEW1.3.1 Identifying research evidence for systematic reviews1.3.1.1 Minimizing publication and language biases1.3.1.2 Searching electronic databases1.3.1.3 Searching other sources1.3.1.4 Constructing the search strategy for electronic databases1.3.1.5 Text mining1.3.1.6 Updating literature searches1.3.1.7 Current awareness1.3.1.8 Managing references1.3.1.9 Obtaining documents1.3.1.10 Documenting the search1.3.2 Study selection1.3.2.1 Process for study selection1.3.3 Data extraction1.3.3.1 Design1.3.3.2 Content1.3.3.3 Software1.3.3.4 Piloting data extraction1.3.3.5 Process of data 1CRD Systematic Reviews.indd 18/1/09 09:28:38

Systematic Reviews1.3.4 Quality assessment1.3.4.1 Introduction1.3.4.2 Defining quality1.3.4.3 The impact of study quality on the estimate of effect1.3.4.4 The process of quality assessment in systematic reviews1.3.5 Data synthesis1.3.5.1 Narrative synthesis1.3.5.2 Quantitative synthesis of comparative studies1.3.6 Report writing1.3.6.1 General considerations1.3.6.2 Executive summary or abstract1.3.6.3 Formulating the discussion1.3.6.4 Conclusions, implications, recommendations1.3.7 Archiving the review1.3.8 Disseminating the findings of systematic reviews1.3.8.1 What is dissemination?1.3.8.2 CRD approach to 4858586912CRD Systematic Reviews.indd 28/1/09 09:28:40

Core principles and methods for conducting a systematic review of health interventions1.1GETTING STARTEDThere are a number of reasons why a new review may be considered. Commissionedcalls for evidence synthesis are usually on topics where a gap in knowledge has beenidentified, prioritised and a question posed. Alternatively the idea for a review may beinvestigator led, with a topic identified from an area of practice or research interest;such approaches may or may not be funded. Whatever the motivation for undertaking areview the preparation and conduct should be rigorous.1.1.1Is a review required?Before undertaking a systematic review it is necessary to check whether there arealready existing or ongoing reviews, and whether a new review is justified. Thisprocess should begin by searching the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects(DARE),1 and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR).2 DARE containscritical appraisals of systematic reviews of the effects of health interventions. CDSRcontains the full text of regularly updated systematic reviews of the effects of healthcare interventions carried out by the Cochrane Collaboration. Other sites to considersearching include, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)and the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (NIHR HTA) programme websites. TheCampbell Collaboration website3 contains the Campbell Library of Systematic Reviewsgiving full details of completed and ongoing systematic reviews in education, crimeand justice, and social welfare; and the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information(EPPI) Centre,4 whose review fields include education, health promotion, social care andwelfare, and public health, has a database of systematic and non systematic reviewsof public health interventions (DoPHER). It may also be worth looking at sites such asthe National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGC)5 or the Scottish Intercollegiate GuidelinesNetwork (SIGN),6 as many guidelines are based on systematic review evidence.Searching the previous year of MEDLINE or other appropriate bibliographic databasesmay be helpful in identifying recently published reviews.If an existing review is identified which addresses the question of interest, then thereview should be assessed to determine whether it is of sufficient quality to guide policyand practice. In general, a good review should focus on a well-defined question anduse appropriate methods. A comprehensive search should have been carried out, clearand appropriate criteria used to select or reject studies, and the process of assessingstudy quality, extracting and synthesising data should have been unbiased, reproducibleand transparent. If these processes are not well-documented, confidence in results andinferences is weakened. The review should report the results of all included studiesclearly, highlighting any similarities or differences between studies, and exploring thereasons for any variations.Critical appraisal can be undertaken with the aid of a checklist7-10 such as the exampleoutlined in Box 1.1. Such checklists focus on identifying flaws in reviews that might biasthe results.8 Quality assessment is important because the effectiveness of interventionsmay be masked or exaggerated by reviews that are not rigorously conducted.Structured abstracts included in the DARE database1 provide worked examples of how achecklist can be used to appraise and summarise reviews.3CRD Systematic Reviews.indd 38/1/09 09:28:40

Systematic ReviewsIf a high quality review is located, but was completed some time ago, then anupdate of the review may be justified. Current relevance will need to be assessedand is particularly important in fields where the research is rapidly evolving. Whereappropriate, collaboration with the original research team may assist in the updateprocess by providing access to the data they used. However, little research has beenconducted on when and how to update systematic reviews and the feasibility andefficiency of the identified approaches is uncertain.11 If a review is of adequate qualityand still relevant, there may be no need to undertake another systematic review.Where a new systematic review or an update is required, the next step is to establish areview team and possibly an advisory group, to develop the review protocol.Box 1.1: Critically appraising review articles Was the review question clearly defined in terms of population, interventions,comparators, outcomes and study designs (PICOS)? Was the search strategy adequate and appropriate? Were there anyrestrictions on language, publication status or publication date? Were preventative steps taken to minimize bias and errors in the studyselection process? Were appropriate criteria used to assess the quality of the primary studies,and were preventative steps taken to minimize bias and errors in the qualityassessment process? Were preventative steps taken to minimize bias and errors in the dataextraction process? Were adequate details presented for each of the primary studies? Were appropriate methods used for data synthesis? Were differences betweenstudies assessed? Were the studies pooled, and if so was it appropriate andmeaningful to do so? Do the authors’ conclusions accurately reflect the evidence that was reviewed?1.1.2The review teamThe review team will manage and conduct the review and should have a range ofskills. Ideally these should include expertise in systematic review methods, informationretrieval, the relevant clinical/topic area, statistics, health economics and/or qualitativeresearch methods where appropriate. It is good practice to have a minimum of tworesearchers involved so that measures to minimize bias and error can be implementedat all stages of the review. Any conflicts of interest should be explicitly noted early inthe process, and steps taken to ensure that these do not impact on the review process.4CRD Systematic Reviews.indd 48/1/09 09:28:40

Core principles and methods for conducting a systematic review of health interventions1.1.3The advisory groupIn addition to the team who will undertake the review there may be a number ofindividuals or groups who are consulted at various stages, including for example healthcare professionals, patient representatives, service users and experts in researchmethods. Some funding bodies require the establishment of an advisory group who willcomment on the protocol and final report and provide input to ensure that the reviewhas practical relevance to likely end users. Even if this is not the case, and even wherethe review team is knowledgeable about the area, it is still valuable to have an advisorygroup whose members can be consulted at key stages.Engaging with stakeholders who are likely to be involved in implementing therecommendations of the review can help to ensure that the review is relevant to theirneeds. The particular form of user involvement will be determined by the purpose of theconsultation. For example, when considering relevant outcomes for the review, usersmay suggest particular aspects of quality of life which it would be appropriate to assess.An example of a review which incorporated the views of users to considerable effect isone evaluating interventions to promote smoking cessation in pregnancy, which includedoutcomes more relevant to users as a result of their involvement.12 However, consultationis time consuming, and needs to be taken into account in the project timetable. Wherereviews have strict time constraints, wide consultation may not be possible.At an early stage, members of the advisory group should discuss the audiences forwhom the review findings are likely to be relevant, helping to start the planning of adissemination strategy from the beginning of the project.The review team may also wish to seek more informal advice from other clinical ormethodological experts who are not members of the advisory group. Likewise, wherean advisory group has not been established, the review team may still seek advice fromrelevant sources.Summary: Getting started Whatever the motivation for undertaking a review the preparation and conductshould be rigorous. A search of resources such as the DARE database should be undertaken tocheck for existing or ongoing reviews, to ensure a new review is justified. A review team should be established to manage and conduct the review. Themembership should provide a range of skills, including expertise in systematicreview methods, information retrieval, the relevant clinical/topic area, statistics,health economics and/or qualitative research methods where appropriate. Formation of an advisory group including, for example, health careprofessionals, patient representatives, services users and experts in researchmethods may be a requirement of some funding bodies. In any event, it maybe valuable to have an advisory group, whose members can be consulted atkey stages. The review team may wish to seek advice from a variety of clinical ormethodological experts, whether or not an advisory group is convened.5CRD Systematic Reviews.indd 58/1/09 09:28:41

Systematic Reviews1.2THE REVIEW PROTOCOL1.2.1IntroductionThe review protocol sets out the methods to be used in the review. Decisions about thereview question, inclusion criteria, search strategy, study selection, data extraction,quality assessment, data synthesis and plans for dissemination should be addressed.Specifying the methods in advance reduces the risk of introducing bias into the review.For example, clear inclusion criteria avoids selecting studies according to whether theirresults reflect a favoured conclusion.If modifications to the protocol are required, these should be clearly documented andjustified. Modifications may arise from a clearer understanding of the review question,and should not be made because of an awareness of the results of individual studies.Further information is given in Section 1.2.4 How to deal with protocol amendmentsduring the review.Protocol development is often an iterative process that requires communication withinthe review team and advisory group and sometimes with the funder.1.2.2Key areas to cover in a review protocolThis section covers the development of the protocol and the information it shouldcontain. The formulation of the review objectives from the review question and thesetting of inclusion criteria are covered in detail here as these must be agreed beforestarting a review. The search strategy, study selection, data extraction, qualityassessment, synthesis and dissemination are also mentioned briefly as they areessential parts of the review protocol. However, to avoid repetition, full details of theissues related to both protocol requirements and carrying out the review are provided inSection 1.3 Undertaking the review.1.2.2.1 BackgroundThe background section should communicate the key contextual factors and conceptualissues relevant to the review question. It should explain why the review is required andprovide the rationale underpinning the inclusion criteria and the focus of the reviewquestion, for example justifying the choice of interventions to be considered in the review.1.2.2.2 Review question and inclusion criteriaSystematic reviews should set clear questions, the answers to which will providemeaningful information that can be used to guide decision-making. These should bestated clearly and precisely in the protocol. Questions may be extremely specific or verybroad, although if broad, it may be more appropriate to break this down into a seriesof related more specific questions. For example a review to ‘assess the evidence on thepositive and negative effects of population-wide drinking water fluoridation strategies toprevent caries’,13 was undertaken by addressing five objectives:6CRD Systematic Reviews.indd 68/1/09 09:28:41

Core principles and methods for conducting a systematic review of health interventionsObjective 1: What are the effects of fluoridation of drinking water supplies on theincidence of caries?Objective 2: If water fluoridation is shown to have beneficial effects, what is theeffect over and above that offered by the use of alternative interventions andstrategies?Objective 3: Does water fluoridation result in a reduction of caries across socialgroups and between geographical locations, bringing equity?Objective 4: Does water fluoridation have negative effects?Objective 5: Are there differences in the effects of natural and artificial waterfluoridation?Where there are several objectives it may be necessary to prioritise by importance andlikelihood of being able to answer the question. It may even be neces

This guide focuses on the methods relating to use of aggregate study level data. Although discussed briefl y in relevant sections, individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis, which is a specifi c method of systematic review, is not described in detail. The basic principles are outlined in Appendix 1 and more detailed guidance can be found