Transcription

MAKING TRADE WORKStraight Talk on Jobs,Trade, and AdjustmentA Statement by theResearch and PolicyCommittee of theCommittee forEconomic DevelopmentMarch 2005

MAKING TRADE WORKStraight Talk on Jobs,Trade, and AdjustmentA Statement by theResearch and PolicyCommittee of theCommittee forEconomic DevelopmentMarch 2005

Making Trade Work: Straight Talk on Jobs, Trade, and Adjustment/ a policy statementby the Research and Policy Committee of the Committee for Economic Development.Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data can be found at theLibrary of Congress.First printing: 2005Paperback: 15.00Printed in the United States of AmericaDesign: Rowe Design GroupCOMMITTEE FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT2000 L Street, N.W., Suite 700, Washington, D.C. 20036(202) 296-5860www.ced.org

CONTENTSRESPONSIBILITY FOR CED STATEMENTS ON NATIONAL POLICY .ivPURPOSE OF THIS STATEMENT .viiSUMMARY: THE NEED TO GET TO “YES” ON TRADE .1TRADE AND JOBS .2WE ARE NOT IN A “NEW ERA”.4THE REALITIES OF OUTSOURCING .4WHAT SHOULD BE OUR RESPONSE TO THE NEGATIVE EFFECTSOF OUTSOURCING? .6OUR EXPERIENCE WITH TRADE ADJUSTMENT .8CONCLUSION .10SUPPLEMENTAL TABLES .11Table 1: Expenditures on Training and Unemployment Programs .11Table 2: Economic Costs of Import Restraints, by Sector .12Table 3: Farm Service Agency, Commodity Program Outlays.13APPENDIX 1: WHAT IS AN ALTERNATIVE APPROACH? .14The Role of Education and Training .15The Importance of Job-Search Assistance .15Other Adjustment Policies .16APPENDIX 2: SUMMARIES OF RELATED MATERIALS .18Introduction .18Current State of Domestic Jobs .18Foreign Outsourcing .20Trade Policy .23Adjustment Assistance/Unemployment Insurance Reform .26Education/Training for Displaced Workers .29ENDNOTES .32MEMORANDUM OF COMMENT, RESERVATION, OR DISSENT.34OBJECTIVES OF THE COMMITTEE FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT .35iii

RESPONSIBILITY FOR CED STATEMENTSON NATIONAL POLICYThe Committee for Economic Development is an independent research and policyorganization of some 250 business leaders andeducators. CED is non-profit, non-partisan,and non-political. Its purpose is to proposepolicies that bring about steady economicgrowth at high employment and reasonablystable prices, increased productivity and livingstandards, greater and more equal opportunity for every citizen, and an improved quality oflife for all.All CED policy recommendations musthave the approval of trustees on the Researchand Policy Committee. This committee isdirected under the bylaws, which emphasizethat “all research is to be thoroughly objectivein character, and the approach in eachinstance is to be from the standpoint of thegeneral welfare and not from that of anyspecial political or economic group.” Thecommittee is aided by a Research AdvisoryBoard of leading social scientists and by a smallpermanent professional staff.The Research and Policy Committee doesnot attempt to pass judgment on any pendingivspecific legislative proposals; its purpose is tourge careful consideration of the objectives setforth in this statement and of the best meansof accomplishing those objectives.Each statement is preceded by extensivediscussions, meetings, and exchange of memoranda. The research is undertaken by a subcommittee, assisted by advisors chosen fortheir competence in the field under study.The full Research and Policy Committeeparticipates in the drafting of recommendations. Likewise, the trustees on the draftingsubcommittee vote to approve or disapprove apolicy statement, and they share with theResearch and Policy Committee the privilegeof submitting individual comments for publication.The recommendations presented herein are thoseof the trustee members of the Research and PolicyCommittee and the responsible subcommittee. Theyare not necessarily endorsed by other trustees or bynon-trustee subcommittee members, advisors, contributors, staff members, or others associated with CED.

RESEARCH AND POLICY COMMITTEECo-ChairmenPATRICK W. GROSSChairman, The Lovell GroupGEORGE H. CONRADESChairman and Chief Executive OfficerAkami Technologies, Inc.CHARLES E.M. KOLBPresidentCommittee for Economic DevelopmentBRUCE K. MACLAURYPresident EmeritusThe Brookings InstitutionRONALD R. DAVENPORTChairman of the BoardSheridan Broadcasting CorporationALONZO L. MCDONALDChairman and Chief Executive OfficerAvenir Group, Inc.Vice ChairmanJOHN DIEBOLDChairmanThe Diebold InstituteNICHOLAS G. MOORESenior AdvisorBechtel Group, Inc.FRANK P. DOYLERetired Executive Vice PresidentGeneral ElectricSTEFFEN E. PALKOVice Chairman and PresidentXTO Energy Inc.T.J. DERMOT DUNPHYChairmanKildare Enterprises, LLCCAROL J. PARRYPresidentCorporate Social ResponsibilityAssociatesIAN ARNOFChairmanArnof Family FoundationREX D. ADAMSProfessor of Business AdministrationThe Fuqua School of BusinessDuke UniversityALAN BELZERRetired President and Chief OperatingOfficerAlliedSignal Inc.PETER A. BENOLIELChairman, Executive CommitteeQuaker Chemical CorporationROY J. BOSTOCKChairman and Chief Executive OfficerSealedge InvestmentsFLETCHER L. BYROMPresident and Chief Executive OfficerMICASU CorporationDONALD R. CALDWELLChairman and Chief Executive OfficerCross Atlantic Capital PartnersCAROLYN CHINChairman and Chief Executive OfficerCebizA. W. CLAUSENRetired Chairman and Chief ExecutiveOfficerBankAmerica CorporationJOHN L. CLENDENINRetired ChairmanBellSouth CorporationCHRISTOPHER D. EARLManaging DirectorPerseus Capital, LLCW. D. EBERLEChairmanManchester Associates, Ltd.EDMUND B. FITZGERALDManaging DirectorWoodmont AssociatesHARRY L. FREEMANChairThe Mark Twain InstituteBARBARA B. GROGANPresidentWestern Industrial ContractorsRICHARD W. HANSELMANChairmanHealth Net Inc.RODERICK M. HILLSChairmanHills & Stern, LLPEDWARD A. KANGASChairman and Chief Executive Officer,RetiredDeloitte Touche TohmatsuJOSEPH E. KASPUTYSChairman, President and ChiefExecutive OfficerGlobal Insight, Inc.VICTOR A. PELSONSenior AdvisorUBS Warburg LLCPETER G. PETERSONChairmanThe Blackstone GroupNED REGANUniversity ProfessorBaruch College, The City University ofNew YorkJAMES Q. RIORDANChairmanQuentin Partners Co.LANDON H. ROWLANDChairmanEverglades FinancialGEORGE RUPPPresidentInternational Rescue CommitteeMATTHEW J. STOVERPresidentLKM VenturesARNOLD R. WEBERPresident EmeritusNorthwestern UniversityJOSH S. WESTONHonorary ChairmanAutomatic Data Processing, Inc.*Voted to approve the policy statement but submitted memoranda of comment, reservation, or dissent, See page 41v

SUBCOMMITTEE ON TRADEChairmanJAMES D. ROBINSON, IIIGeneral Partner & FounderRRE VenturesMembersCOUNTESS MARIA BEATRICE ARCOChairAmerican Asset CorporationIAN ARNOFRetired ChairmanBank One, Louisiana, N.A.JAMES S. BEARDPresidentCaterpillar Financial Services Corp.JEFFREY A. JOERRESChairman, President andChief Executive OfficerManpower Inc.H. V. JONESManaging DirectorKorn/Ferry International, Inc.JOSEPH E. KASPUTYSChairman, President andChief Executive OfficerGlobal Insight, Inc.L.R. WILSONChairmanNortel Networks CorporationJACOB J. WORENKLEINPresident and Chief Executive OfficerUS Power Generating Company, LLCRONALD L. ZARRELAChairman and Chief Executive OfficerBausch & Lomb, Inc.ALFRED T. MOCKETTEx-Officio MembersNICHOLAS G. MOORESenior AdvisorBechtel Group, Inc.ROY J. BOSTOCKChairman and Chief Executive OfficerSealedge InvestmentsMATTHEW NIMETZPartnerGeneral Atlantic PartnersPATRICK W. GROSSChairman, The Lovell GroupFounder, AMSPETER A. BENOLIELChairman, Executive CommitteeQuaker Chemical CorporationDEAN R. O’HAREChairman and Chief Executive Officer,RetiredChubb CorporationCHARLES KOLBPresidentCommittee for Economic DevelopmentSENATOR WILLIAM E. BROCKChairmanBridges Learning Systems, Inc.DONALD K. PETERSONChairman and Chief Executive OfficerAvaya Inc.WILLIAM W. LEWISDirector Emeritus, McKinsey GlobalInstituteMcKinsey & Company, IncDAVID A. CAPUTOPresidentPace UniversityRAYMOND PLANKChairmanApache CorporationDAVID M. COTEChairman, President, andChief Executive OfficerHoneywell International Inc.LANDON H. ROWLANDChairmanEver Glades FinancialJOHN DIEBOLDChairmanThe Diebold InstituteLINDA M. DISTLERATHVice President, Global Health PolicyMerck & Co., Inc.W.D. EBERLEChairmanManchester Associates, Ltd.G. STEVEN FARRISPresident, Chief Executive Officer andChief Operating OfficerApache CorporationJOHN C. SICILIANODirector, Global Institutional ServicesDimensional Fund AdvisorsFREDERICK W. SMITHChairman, President andChief Executive OfficerFedEx Corporation* THE HONORABLE PAULA STERNChairwomanThe Stern Group, Inc.LAWRENCE SUMMERSPresidentHarvard UniversityBRUCE K. MACLAURYPresident EmeritusThe Brookings InstitutionNon-Trustee MembersM. MICHEL ORBANPartnerRRE VenturesAdvisorISAIAH FRANKWilliam L. Clayton Professor ofInternational EconomicsThe School of Advanced InternationalStudiesJohn Hopkins UniversityEDMUND B. FITZGERALDManaging DirectorWoodmont AssociatesFREDERICK W. TELLINGVice President, Corporate Policy &Strategic ManagementPfizer Inc.HARRY L. FREEMANChairmanThe Mark Twain InstituteSTEPHEN JOEL TRACHTENBERGPresidentGeorge Washington UniversityEVERETT EHRLICHSenior Vice President and Director ofResearchCommittee for Economic DevelopmentPAMELA GANNPresidentClaremont McKenna CollegeFRANK VOGLPresidentVogl CommunicationsProject AssociateRODERICK M. HILLSChairmanHills & Stern, LLPJOSH S. WESTONHonorary ChairmanAutomatic Data Processing, Inc.TRACY KORNBLATTResearch AssociateCommittee for Economic DevelopmentProject Director*Voted to approve the policy statement but submitted memorandum of comment, reservation, or dissent, See page 34vi

PURPOSE OF THIS STATEMENTThis policy statement presents a clearvision of the need for a strong and openglobal trading system, and lays out the kindsof policies necessary to make trade work forall Americans. It explains how existing programs could be refined and extended to helpthose workers who are adversely affected bytrade to take advantage of the new andexpanded opportunities that come from opentrade.The body of the paper makes the case fora comprehensive agenda to achieve opentrade, and to address the hardship of thosewho may lose their livelihoods as a result ofeconomic change. It is short by CED standards in order to be a direct call for actionfor a comprehensive agenda. The first appendix provides greater detail on how such policies can be designed and implemented; thesecond appendix adds background information on key topics. The statement should beread in its entirety, including the appendices.on page vi. We are grateful for the time,efforts, and care that each put into thedevelopment of this report.Special thanks go to the subcommitteechair, James D. Robinson, III, whose leadership and tireless efforts made this statementpossible. Thanks are also due to MichelOrban for her work in shepherding the project from beginning to end. Everett Ehrlich,CED’s Senior Vice President and Director ofResearch, served as project manager. Thanksare also due to Isaiah Frank, CED’s Advisoron International Economic Policy, for hissubstantial contributions throughout thisproject, and to Tracy Kornblatt, who providedresearch assistance.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThis policy statement was developed bythe committed and knowledgeable group ofbusiness, academic, and policy leaders listedBruce K. MacLaury, Co-ChairResearch and Policy CommitteePresident EmeritusThe Brookings InstitutionPatrick W. Gross, Co-ChairResearch and Policy CommitteeChairman, The Lovell GroupFounder and Senior Advisor, AMSvii

SUMMARY:THE NEED TO GET TO “YES” ON TRADEThe trade outlook in the United States is acause of deep concern. The nation’s tradedeficit has reached record levels, sending thecurrent account deficit, and our accumulatedinternational investment imbalance, to alltime highs. And in the meantime, ongoingtrade liberalization efforts — the negotiationof the multilateral Doha Round, and attemptsto finalize the CAFTA agreement in our ownhemisphere — appear to have lost momentum.Still, the significant long-term benefits ofopen trade and "outsourcing" to theAmerican economy have been widely demonstrated. Trade gives our economy lower-costgoods and gives our companies the resourcesto be competitive. Trade is a substantial partof the exceptional dynamism that creates jobsand growth in America. This is no time tolose our resolve to enhance U.S. prosperitythrough trade.Proponents of open trade must recognizethat one of the greatest roadblocks to tradeliberalization is the dislocation experiencedby many workers who lose their livelihoodsand whose skills may be made unmarketableby economic change. Their hardship is theprice a growing economy pays for the benefits of trade in particular, and change in general. And just as it would be irresponsible toadvocate that we limit trade — and thereforelimit our standard of living — in a futileeffort to "protect" these displaced workers, itis unacceptable to advocate open trade without addressing concretely the hardshipimposed by these dislocations.Open trade should and must be a cornerstone of America's economic policy. It buildsour economy, enhances our security, and supports American diplomacy around the world.We need to forge a national consensus to sup-port this goal, and adjustment policy must bea vital part of how we get to "yes" on trade.Many sound analyses have shown thattrade is not the cause of the economy's recentslow pace of job creation; CED cites thesestudies in an appendix attached to this statement. But while we concur, we realize thatthe fear of job loss is very real and makes itdifficult for workers to embrace more opentrade.Getting to "yes" on trade, therefore, meansestablishing an aggressive and effective adjustment policy that helps workers in transition.But it is not yet clear what forms such policyshould ultimately take. The purpose of thispolicy statement, therefore, is not to proposea specific program for adjustment. Rather, itis to create greater momentum for a substantive dialogue among all interested parties todevelop an effective and timely adjustmentpolicy, and to discuss some highly promisingideas for such a policy.In its previous work, CED has expressedsupport for a wage-insurance program thatwould protect workers from income lossesassociated with job change, as well as helpworkers with job search, health coverage, andtraining. We recognize that there are someworkers for whom job loss may presentextremely difficult circumstances, in partbecause they may lack the skills or the training to reenter the workforce. Our adjustmentpolicies must recognize the legitimacy of theirneeds, eschew a “one size fits all” approach,and make every possible effort to encourageand facilitate their reemployment.Previous efforts to forge this kind ofadjustment policy have been marked by halfheartedness and fragmentation. Differingpolitical agendas through the years have created many incremental programs. The aggre1

MAKING TRADE WORK: STRAIGHT TALK ON JOBS, TRADE, AND ADJUSTMENTgate cost of numerous adjustment and training programs is already large; the benefits ofrationalizing and integrating these programs,and of eliminating various trade-distortingsubsidy programs, would allow us readily toafford the cost of addressing more effectivelythe plight of displaced workers. And in fact,we believe that adjustment programs, unlikethe current Trade Adjustment Assistance(TAA) system, could and should be availableto all workers experiencing involuntary unemployment, for reasons other than their ownconduct, and should emphasize, wheneverpossible, getting back to work.CED believes that business organizationssuch as our own must reach out to labor andto other groups to initiate the leadership tomake the changes needed to form a consensus around trade policy, of which tradeadjustment must be a central part. Only sucha collective effort can address the prevailingmisunderstanding and mistrust. In thispolicy statement, we present our case fordoing so.TRADE AND JOBSOutsourcing has received much attentionin recent months as a reason for slow jobgrowth. But trade and outsourcing have hadlittle effect on job growth — rather, a modesteconomic recovery coupled with high rates ofproductivity growth are the prime causes ofthe recent slow growth in employment.1 (Anaccompanying box, Slow Job Growth: Tradeor Productivity, presents this issue in greaterdetail.) Now that job growth has resumed at astronger pace, these concerns might abate.But more industries will still be in the throesof structural change, often related to technological advances. Economists at the FederalReserve have shown that a far higher share ofthe workforce is in such industries today thanin previous periods.2More structural change in the economymeans that more workers will be forced tofind new jobs and acquire new skills. This, inturn, has created concern among many working families. Stories of displacement and jobloss are featured on the news and brandished, often irresponsibly, by commentators.Workers in industries, firms, and occupationsonce thought immune to competitive pressure are now reacting with concern.2The alarm over services “outsourcing” perfectly captures these fears; the idea that someprogramming tasks or customer call centerscan be moved outside the United States is anew and pressing challenge to workers’ perceptions of the economy and their role in it.Trade has become the lightning rod for thisfear. It is easy to count the jobs lost throughoutsourcing, but difficult to count the manyjobs created through the cost savings createdby outsourcing, the productivity growth itallows, and direct foreign investment in theUnited States — they are “hidden in plainsight.” But, in a larger sense, the debate overthe effect trade has on jobs misses the point— structural change, the result of trade andtechnological progress, is growing and is hereto stay; the explosive growth of the Internetand the burgeoning power of informationtechnology will be forces in our economy fordecades to come. The upshot is that we mustdevelop policies to accommodate these forceswhile letting them play their central role indelivering economic growth.

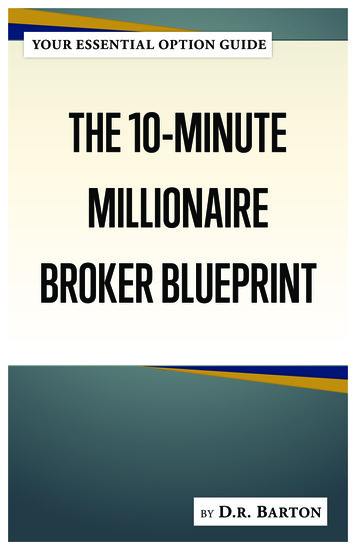

Trade and JobsSLOW JOB GROWTH: TRADE OR PRODUCTIVITY?Most economists believe that a sluggish economic recovery, coupled with rapid productivitygrowth — not trade — are responsible for recent slow job growth. The evidence supports their view.For example, trade growth in the 1990s coincided with rapid job growth. Furthermore, in thecurrent cycle, total imports into the economy other than crude oil in 2003 were only 50 billionhigher than they were in 2000 — which is just under one-half of one percent of the size of the totaleconomy. It is impossible to explain the loss of 2.7 million jobs — two percent of the labor force —with a change of imports of that magnitude. What, then, explains the problem?The answer is in part that the economic recovery from the 2001 recession was tepid — which wasunderstandable, given that the recession itself was shallow, and that the sectors that suffered mostwere not those that typically lead a rebound. In fact, cumulative growth in the first eight quartersof the 2001 recovery has lagged the rebounds of the 1975, 1982 and 1991 recoveries by almost3 percent of GDP, the equivalent of about four million jobs.In addition, labor productivity growth has been remarkably strong. As seen in the chart below,productivity growth always takes off in the initial quarters of an expansion due to the “bounce back”after a recession. But in this expansion, that initial surge has been sustained far longer than in previous recoveries. This figure implies that the cumulative level of productivity gain achieved in thisexpansion to date is about 3 percent higher than in all other recent expansions. This means thatthe demand for labor in the entire U.S. economy is 3 percent lower than it would have been inprevious periods, due to higher productivity — which would account for a difference of four millionjobs. Simply put, productivity growth, not trade, is the primary driver of recent slow job growth.Cumulative Productivity Growth in Quarters Following Trough of Recession(measured in output per hour)Cumulative productivity growth (percentage)1091975 recovery81982 recovery71991 recovery62001 recovery543210TroughQ1Q2Q3Q4Q5Q6Q7Q8Quarters following troughSOURCE: CED, with data from the U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics.3

MAKING TRADE WORK: STRAIGHT TALK ON JOBS, TRADE, AND ADJUSTMENTWE ARE NOT IN A “NEW ERA”Some observers have labeled the currentchallenge as a new era in the economy thatrequires a new response.3 But while the paceof change may be formidable, the nature ofeconomic change is entirely familiar. Callcenters, for example, may only now bemigrating to South Asia, but earlier theymigrated from the Northeast to the farmstates. Textile production left New Englandfor the South before it located elsewhere.Similarly, while computers are an epochaltechnology, the economy has been transformed by other epochal technologies in thepast — from the cotton gin to interchangeable parts to the automobile and the airplane. Even foreign outsourcing is not new.Foreign outsourcing has been continuing fordecades — twenty years ago, the fear was thatAmerica’s children would grow up to “cleanup around Japanese computers” — butstronger domestic job growth made suchdevelopments of little concern to Americanworkers. Only a recent cycle of slow jobgrowth has brought attention to foreign outsourcing as a threat.The reality is this: Change and growth areinseparable. The economy grows and ourstandard of living rises because new and better activities replace old and less productiveones. If that were not true, we would still be anation of artisans and mule drivers, with acomparable standard of living. We may facean era of greater, ongoing economic change,but historically change has characterized oureconomy. Trying to restrict this age-oldprocess would be counterproductive — aneconomic disaster. Helping the Americanpeople manage change is the only tenableresponse.THE REALITIES OF OUTSOURCINGA plant closing and job loss from outsourcing are easy to observe. But that is not theend of the story. In a broader context, outsourcing is a source of job creation as well asdestruction, and this "net" effect is the oneon which we should focus.Some jobs are obviously lost to foreignoutsourcing. Forrester, a leading informationtechnology analyst, predicts that about473,000 information technology jobs — eightpercent of all such jobs today — will migrateoverseas in the next twelve years, and 3.3million total jobs will be outsourced over thenext fifteen years.4 But while the jobs lost arereal, less than 0.2 percent of American workers would be affected if Forrester’s predictions were to hold.5Moreover, if outsourcing were truly a forcefor job loss, we would be losing our technology employment base.* But on the contrary,the Bureau of Labor Statistics, among otherauthorities, predicts that job growth from thepresent to 2010 in occupations requiringinformation technology skills will rise morethan three times faster than the rate of jobgrowth in the overall economy. Jobs for such*See memorandum by PAULA STERN (page 34).4

The Realities of Outsourcingskilled positions as medical assistants and network systems analysts are predicted to growby over 55 percent during that period.Outsourcing has a positive effect becauseit is part of a larger and more positive processin the economy — the process of competition, in which more efficient suppliers gainbusiness and drive costs down for the users oftheir goods and services. It leads to some jobsbeing moved, to be sure. But what matterseven more are the productivity gains that areachieved through foreign outsourcing. Thesegains mean cost savings and enhanced competitiveness for U.S. companies, which lead tofollow-on growth and job gains.Software and services are outsourcedbecause it brings down their costs, thus making the use of information technology inbusiness practices more affordable. Throughre-engineered business processes, efficientdatabases, and instantaneous communication,businesses will be able to produce goods andservices in a more efficient and cost-effectivemanner. Thus, the greater diffusion of information technology throughout the U.S. economy will increase the demand for workerswith technology skills. As Catherine Mann hasnoted, the result will be a wave of productivitygrowth analogous to the one we experiencedas computer hardware became cheaper inrecent decades.6 The same technologicalinnovations and management practices thatproduced outsourcing enable America toproduce such competitive successes as eBay,Amazon, and Google, and thousands of newjobs along with them. The upshot, therefore,is that while the immediate and gross effectof outsourcing is negative, in the longer term,the net effect is positive.An additional aspect of the outsourcingprocess is that the United States is the recipient of outsourced jobs from other countries,recently termed "insourcing." In fact, theUnited States is said to insource many morejobs than we outsource. Honda increased itsU.S. manufacturing in 2003 by 15 percent;Novartis is moving its world-wide researchand development operation from Switzerlandto Massachusetts.7 In total, the affiliates offoreign (non-bank) companies operating inthe United States accounted for 6.4 millionAmerican jobs in 2001, and jobs created byforeign direct investment into the UnitedStates equal those created by U.S. affiliatesabroad. Insourcing firms account for a risingshare of U.S. payroll, capital investment, andHOW MANY JOBS WILL “OUTSOURCING” CREATE?Estimates of jobs lost or gained need to be treated with circumspection. The number of jobs inthe economy and the wages they pay are determined, of course, by the supply and demand for labor.When workers lose jobs, those workers don’t disappear — some (typically, most) find other jobs —meaning that job “losses” do not necessarily mean more long-term unemployed, but could meandownward pressure on the wages of those workers. Correspondingly, however, as outsourcing makesthe economy more productive, other jobs will be created, and those wages will potentially rise.For example, Catherine Mann of the Institute for International Economics estimates that, in acomparable situation, outsourcing of computer hardware manufacturing resulted in productivitygains of 0.3 percent a year.† If outsourcing of computer software and services production were toproduce comparable gains (which is entirely credible, as more is spent in the economy on thesecategories than on hardware), then the added 0.3 percent of income created will put upwardpressure on both the number of jobs and wages. This is 50 percent greater than the estimated 0.2percent direct loss of income due to outsourcing, according to Forrester. Thus, more income — andtherefore jobs and wages — is created by outsourcing than is destroyed.† Catherine Mann, Globalization of IT Services and White Collar Jobs: The Next Wave of Productivity Growth, Paper No. PB03-11(Washington, D.C.: Institute for International Economics, December 2003).5

MAKING TRADE WORK: STRAIGHT TALK ON JOBS, TRADE, AND ADJUSTMENTresearch and development.8 By keeping itseconomy open, the United States continuesto be a magnet for companies seeking anenvironment with the legal structure, economic and political stability, and propertyrights that foster innovation, productivity,and growth.Moreover, researchers who have studiedthe characteristics of production plants haveshown that plants managed by multinationalfirms were less likely to shut d

The Mark Twain Institute PAMELA GANN President Claremont McKenna College RODERICK M. HILLS Chairman Hills & Stern, LLP JEFFREY A. JOERRES Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer Manpower Inc. H. V. JONES Managing Director Korn/Ferry International, Inc. JOSEPH E. KASPUTYS Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer Global Insight .