Transcription

Cvr book 1/9/15 8:13 AM Page 2the child who stutters:to the pediatrician5th editionSTUTTERINGFOUNDATION A Nonprofit OrganizationSince 1947— Helping Those Who Stutterpublication no. 0023www.StutteringHelp.orgwww.tartamudez.org

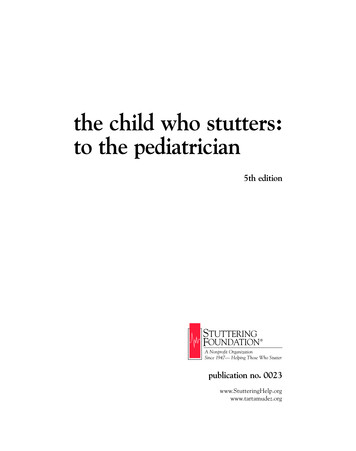

Cvr book 1/9/15 8:13 AM Page 3Risk Factor ChartPlace a check next to each that is true for the childRisk FactorElevated RiskFamily historyof stutteringA parent, sibling,or other familymember who still stuttersAge at onsetAfter age 31/2Time since onsetStuttering 6–12 monthsor longerGenderOther speech productionconcernsLanguage skillsTrue for ChildMaleSpeech sound errors ortrouble being understoodAdvanced, delayed,or disorderedPlease see pages 4 and 5 for more information.www.StutteringHelp.org www.tartamudez.orgCopyright 2001-2013 by the Stuttering Foundation of AmericaTHE STUTTERING FOUNDATION800-992-9392

PedBook book 1/9/15 8:11 AM Page 1the child who stutters:to the pediatrician5th editionBarry Guitar, Ph.D.Professor,Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders,University of VermontEdward G. Conture, Ph.D.Professor Emeritus,Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences,Vanderbilt UniversityEditorial assistance:Stephen Contompasis, M.D.,Associate Professor of Pediatrics,University of Vermont Medical SchoolUniversity of VermontJane FraserPresident,The Stuttering FoundationMichael B. Grizzard, M.D.,Medical Director,The World Bank, Washington, D.C.Ellen Kelly, Ph.D.,Associate Professor,Department of Hearing and Speech SciencesVanderbilt University School of MedicineJames McKay, M.D.,*Professor Emeritus of Pediatrics,College of Medicine,University of VermontPeter Ramig, Ph.D.,Professor Emeritus,Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing SciencesUniversity of Colorado–BoulderPatricia M. Zebrowski, Ph.D.,Professor,Department of Speech Pathology and Audiology,University of IowaThe Stuttering FoundationPublication No. 0023www.StutteringHelp.org www.tartamudez.org

PedBook book 1/9/15 8:11 AM Page 2the child who stutters:to the pediatricianPublication No. 0023First Edition—1991Second Edition—2001Third Edition—2004Fourth Edition—2006Revised Fourth Edition—2007Fifth Edition—2013Published byStuttering Foundation of AmericaP. O. Box 11749Memphis, Tennessee 38111-0749ISBN 978-0-933388-80-2Copyright 2001, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2013, 2015by Stuttering Foundation of AmericaThe Stuttering Foundation of America is a nonprofitcharitable organization dedicated to the preventionand improved treatment of stuttering.

PedBook book 1/9/15 8:11 AM Page 3The Child Who Stutters:To the PediatricianMost children go through periods of disfluency as they learn to speak.Some will experience mild stuttering, and for others the difficulty willbecome severe. Early intervention by the pediatrician can help parentsunderstand and thus minimize the problem.EtiologyAlthough the etiology of stuttering is not fully understood,there is strong evidence tosuggest that it emerges from acombination of constitutionaland environmental factors.Geneticists have found indications that a susceptibility tostuttering may be inherited andthat it is most likely tooccur in boys.1,6,9,17,18 Furthersupport for inheritance comesfrom twin studies that havedemonstrated a higher concordance for stuttering among bothmembers of identical twin pairsthan fraternal twin pairs.Congenital brain damage is alsosuspected to be a predisposingfactor in some cases. For mostchildren who stutter, however,there is no clear evidence ofbrain damage.1,7,9,17,18Brain imaging studies conducted in many laboratoriesthroughout the world indicatethat adults who stutter showdistinct anomalies in brainfunction. 10 In contrast withnormal speakers, individualswho stutter show deactivationof left-hemisphere sensorimotor centers and over-activation of homologous righthemisphere structures duringboth stuttered and nonstuttered speech. The essentialdefect is hypothesized to be alack of sensorimotor integration necessary to regulate therapid movements of fluentspeech. Both temporary fluency (induced through singing orchoral reading) and more permanent fluency (as a result ofbehavioral treatments) appear to normalize the activation patterns.3,4,5,7,13The onset of stuttering istypically during the period ofintense speech and languagedevelopment as the child isprogressing from 2-word utterances to the use of complexsentences, generally betweenthe ages of 2 and 5 but some-3times as early as 18 months.The child’s efforts at learningto talk and the normal stresses of growing up may be theimmediate precipitants of thebrief repetitions, hesitations,and sound prolongations thatcharacterize early stutteringas well as normal disfluency*.These first signs of stutteringgradually diminish and thendisappear in most children,but some children continue tostutter. In fact, they may begin to exhibit longer and morephysically tense speech behaviors as they respond totheir speaking difficultieswith embarrassment, fear, orfrustration. If referral to aspeech-language pathologistfor parent counseling andtreatment is made before the*The term “disfluency” means a hesitation,interruption, or disruption in speech. It maybe normal or, as in the case of stuttering,it may be abnormal.

PedBook book 1/9/15 8:11 AM Page 4StutteringRisk Factor ChartPlace a check next to each that is true for the childRisk FactorElevated RiskFamily historyof stutteringA parent, sibling,or other familymember who still stuttersAge at onsetTime since onsetGenderOther speech productionconcernsLanguage skillsTrue for ChildAfter age 3 /1 Age at onsetChildren who begin stutteringbefore age 3 1/2 are more likely tooutgrow stuttering; if the childbegins stuttering before age 3,there is a much better chance shewill outgrow it within 6 months.2Stuttering 6–12 monthsor longerMaleSpeech sound errors ortrouble being understoodAdvanced, delayed,or disorderedCopyright 2001-2015 by the Stuttering Foundation of Americachild has developed a serioussocial and emotional responseto stuttering, prognosis for recovery is good.3,17,18Prevalence, Incidence,and Risk Factorsfor Chronicity*About 5% of all children gothrough a period of stutteringthat lasts six months or more.Three-quarters of those whobegin to stutter will recover by Family historyThere is now strong evidencethat about 60 percent of all children who stutter have a familymember who stutters. The riskthat the child is actually stutteringinstead of just having normal disfluencies increases if that familymember is still stuttering. There isless risk if the family member outgrew stuttering as a child.late childhood, leaving about 1%of the population with a longterm problem. The sex ratio forstuttering appears to be almostequal at the onset of the disorder, but studies indicate thatamong those children who continue to stutter, that is, schoolage children, there are three tofour times as many boys whostutter as there are girls.9,18Risk factors that predict achronic problem rather thanspontaneous recovery includethe following:16,174 Time since onsetBetween 75% and 80% of allchildren who begin stuttering willbegin to show improvement within 12 to 24 months without speechtherapy. If the child has been stuttering longer than 6 months, or ifthe stuttering has worsened, hemay be less likely to outgrow it onhis own. If he has been stutteringlonger than 12 months with noimprovement, there is an evensmaller likelihood he will outgrowit on his own. GenderGirls are more likely than boysto outgrow stuttering. In fact,three to four boys continue to stutter for every girl who stutters.Why this difference? First, it appears that during early childhood,there are innate differences between boys’ and girls’ speech andlanguage abilities. Second, duringthis same period, parents, familymembers, and others often reactto boys somewhat differently than

PedBook book 1/9/15 8:11 AM Page 5Stutteringgirls. Therefore, it may be thatmore boys stutter than girls because of basic differences in boys'speech and language abilities anddifferences in their interactionswith others. Other speech and languagefactorsA child who speaks clearlywith few, if any, speech errorswould be more likely to outgrow stuttering than a childwhose speech errors make himdifficult to understand. If thechild makes frequent speech errors such as substituting onesound for another or leavingsounds out of words, or hastrouble following directions,there should be more concern.The most recent findings dispelprevious reports that childrenwho begin stuttering have, as agroup, lower language skills.On the contrary, there are indications that they are well within the norms or above. In fact,advanced language skills appear to be even more of a riskfactor for children whose stuttering persists.15,17,18At present, none of these riskfactors appears, by itself, sufficient to indicate a chronicproblem; rather it is the cumulative or additive nature ofsuch factors that appears todifferentiate children for whomstuttering comes and goes versus those for whom stutteringcomes and stays.The Physician’s RoleThe physician is often the firstprofessional to whom a parentturns for help. Knowing thedifference between normal developmental speech disfluencyand potentially chronic stuttering enables the physician toadvise parents and refer whenappropriate. Early intervention for stuttering—whichmay range from parent counseling and indirect treatmentto direct instruction—can be amajor factor in preventing alife-long problem.Data from several differenttreatment programs indicatesubstantial recovery if treatment is initiated in thepreschool years.7,13,16,17,18*Longitudinal research studies by Drs. Ehud Yairi and Nicoline G. Ambrose and colleaguesat the University of Illinois provide excellent new information about the development of stuttering in early childhood. Their findings are helping speech-language pathologists determinewho is most likely to outgrow stuttering versus who is most likely to develop a lifelong stuttering problem. Research reports includeYairi, E. & Ambrose, N. (2005). Early Childhood Stuttering: For Clinicians by Clinicians,ProEd, Austin, TX.Yairi, E. & Ambrose, N. (1999). Early childhood stuttering I: Persistence and recovery rates.Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42, 1097-1112.Ambrose, N. & Yairi, E. (1999). Normative disfluency data for early childhood stuttering.Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42, 895-909.Yairi, E. & Ambrose, N. (1992). A longitudinal study of stuttering in children: A preliminaryreport. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 35, 755-760.5Differential DiagnosisNormal developmental disfluency and early signs ofstuttering are often difficult todifferentiate. Thus, diagnosis of astuttering problem is madetentatively. It is based upon bothdirect observation of the childand information from parentsabout the child’s speech in different situations and at differenttimes. The following sectionshould help the physician makeappropriate referrals as needed.Normal DisfluencyBetween the ages of 18 monthsand 7 years, many children passthrough stages of speech disfluency associated with theirattempts to learn how to talk.Children with normal disfluenciesbetween 18 months and 3 yearswill exhibit repetitions of sounds,syllables, and words, especially atthe beginning of sentences. Theseoccur usually about once in everyten sentences.After 3 years of age, childrenwith normal disfluencies are lesslikely to repeat sounds or syllables but will instead repeat wholewords (I-I-I can’t) and phrases(I want I want I want to go).They will also commonly usefillers such as “uh” or “um” andsometimes switch topics inthe middle of a sentence,revising and leaving sentencesunfinished.All children may be disfluent at any time and are likelyto increase their disfluencieswhen they are tired, excited,upset, or being rushed to

PedBook book 1/9/15 8:11 AM Page 6Stutteringbe extremely sensitive to speechdevelopment and will becomeunnecessarily concerned aboutnormal disfluencies. Theseoverly concerned parents oftenbenefit from referral to a speechclinician for an evaluation andcontinued reassurance.Mild StutteringTake-Home MessageParents don’t causestuttering, but thereis a lot they can doto help.Suggestions for parents can befound on page 14.speak. They also may be moredisfluent when they ask questions or when someone asksthem questions.Their disfluencies may increase in frequency for severaldays or weeks and then behardly noticeable for weeks ormonths, only to return again.Typically, children with normal disfluencies appear to beunaware of them, showing nosigns of surprise or frustration.Parents show a wider range ofreactions to normal disfluenciesthan their children do. Mostparents will not notice theirchild’s disfluencies or will treatthem as normal.Some parents, however, mayMild stuttering may begin at anytime between the ages of 18months and 7 years but most frequently begins between 2 and 5years, when language development is particularly rapid. Somechildren’s stuttering first appears under conditions of normalstress, such as when a new sibling is born or when the familymoves to a new home.Children who stutter mildlymay show the same sound, syllable, and word repetitions as children with normal disfluenciesbut may have a higher frequencyof repetitions overall as well asmore repetitions each time.For example, instead of one ortwo repetitions of a syllable,they may repeat it four or fivetimes, as in “Ca-ca-ca-ca-can Ihave that?”They may also occasionallyprolong sounds, as in “MMMMMMMommy, it’s mmmmmyball.” In addition to these speechbehaviors, children with mildstuttering may show signs ofreacting to their disfluency.For example, they may blink orclose their eyes, look to the side,or tense their mouths when theystutter.Another sign of mild stutteringis the increasing persistence of6disfluencies. As suggested earlier,normal disfluencies will appearfor a few days and then disappear. Mild stuttering, on theother hand, tends to appear moreregularly. It may occur only inspecific situations, but it is morelikely to occur in these situations,day after day. A third sign associated with mild stuttering is thatthe child may not be deeply concerned about the problem butmay be temporarily embarrassedor frustrated by it. Children atthis stage of the disorder mayeven ask their parents why theyhave trouble talking.Parents’ responses to mildstuttering will vary.3 Most will beat least mildly concerned about itand wonder what they should doand whether they have causedthe problem. These parents willneed reassurance that they donot cause stuttering. A few willtruly not notice it; stillothers may be quite concernedbut deny their concern at first.Severe StutteringChildren with severe stutteringusually show signs of physicalstruggle, increased physical tension, and attempts to hide theirstuttering and avoid speaking.Although severe stuttering ismore common in older children, itcan begin anytime between ages11/2 and 7 years. In some cases, itappears after children have beenstuttering mildly for months oryears. In other cases, severe stuttering may appear suddenly fromone day to the next.Severe stuttering is characterized by speech disfluencies in

PedBook book 1/9/15 8:11 AM Page 7StutteringCase Example: Sally, a child withMild StutteringSally’s mother and father were concerned because Sally, age3, was beginning to avoid speaking. The problem had begunseveral months earlier when Sally was repeating parts ofwords, like, “Ca-ca-ca-can I ha-ha-ha-have some?” Then afew weeks ago she had difficulty getting started making thefirst sound of a word. She would open her mouth, quite wideat times, but nothing would come out. Once she asked hermom, “Why can’t I talk?”Sally’s speech and language development had beennormal. She began using single words at an early age—9months—and was speaking in 2–3 word sentences by 13months. She talked fluently and enjoyed the family’s fastpaced conversations and word games.When Sally’s father discussed her speech with Sally’spediatrician, she referred Sally to a speech-languagepathologist in private practice who was known to haveexpertise in stuttering. Once-a-week treatment sessionsconsisted of parent counseling and play-oriented interactionsbetween Sally, her parents,and her speech clinician.Over a period of six monthsthe clinician’s relaxed,accepting style, combinedwith Sally’s parents’changes in the intensityof speech and languagestimulation at home, workedto reduce Sally’savoidance of speakingand her inability to getsounds started. Shecontinued to show aslightly greater thannormal number of wordrepetitions and phraserepetition for severalmore years and graduallydeveloped normal speech.7

PedBook book 1/9/15 8:11 AM Page 8StutteringCase Example: Barbara, a child withMild StutteringWhen Barbara was 3, her pediatrician noticed shewas repeating and prolonging sounds when hetalked to her. He discussed this with her mother andfather and found them to be aware of it. In fact, theyhad been instructing her to stop and start over againwhen she repeated sounds. He gave them guidanceabout speaking with their child in an unhurried manner,pausing frequently, and refraining from criticism.When her parents brought Barbara to his office sixmonths later for a minor illness the pediatricianinquired about her speech. Barbara’s parents werefrustrated by the lack of change in her speech and hadbegun to correct her again. Barbara herself seemedreluctant to talk to him. The pediatrician referred Barbarato a speech-language pathologist and continued tocounsel the parents to ease conversational pressureson Barbara and refrain from direct correction.A month later, the pediatrician received a copy ofthe speech-language pathologist’s written evaluationof Barbara. This indicated that her stuttering hadprogressed from mild to severe and that the parentsseemed willing to change some key variables in thehome speaking environment. The plan for treatmentincluded some direct treatment of Barbara’sstuttering in the speech clinic.Several months later, Barbara’s parents brought herto the pediatrician for treatment of an infected insect bite.The pediatrician noticed that Barbara’s speech seemedto be the same as before. The parents indicated that theydidn’t see the sense in using slower speech ratesthemselves and have continued to try to correct Barbara’sstuttering by instructions. They had discontinued speechtherapy because they were unable to afford it. At presentthe pediatrician has given them a copy of the StutteringFoundation’s If Your Child Stutters: A Guide for Parents,and Stuttering and Your Child: Questions and Answersand is counseling them to continue changes at home.8

PedBook book 1/9/15 8:11 AM Page 9Stutteringpractically every phrase orsentence; often moments of stuttering are one second or longerin duration. Prolongations ofsounds and silent blockages ofspeech are common.The severely stuttering childmay, like the milder stutterer,have behaviors associated withstuttering: eye blinks, eye closing, looking away, or physicaltension around the mouth andother parts of the face. Moreover, some of the struggle andtension may be heard in a risingpitch of the voice during repetitions and prolongations. Thechild with severe stuttering mayalso use extra sounds like “um,”“uh,” or “well” to begin a wordon which he expects to stutter.This stuttering is morelikely to persist, especially inchildren who have been stuttering for 18 months or longer,although even some of thesechildren will recover spontaneously. The frustration andembarrassment associated withreal difficulty in talking maycreate a fear of speaking. Children with severe stuttering often appear anxious or guardedin situations in which they expect to be asked to talk. Whilethe child’s stuttering will probably occur every day, it will probably be more apparent on somedays than others.Parents of children who stutter severely inevitably havesome degree of concern aboutwhether their child will alwaysstutter and about how they canbest help. Many parents alsobelieve, mistakenly, that theyhave done something to causeTake-Home MessageA child who stutters often feels that he is theonly one to have the problem. He willappreciate hearing from his pediatrician thatother children stutter, too.the stuttering. Parents have notdone anything to cause the stuttering, yet they may still feel responsible for the problem.They will benefit from reassurance that their child’s stutteringis a result of many causes andnot simply the effect of something they did or didn’t do.Some guidelines are summarized in Table 1 on page 13.Counseling ParentsCounseling Parents of aChild with DisfluenciesIf a child appears to be disfluent,parents should be reassuredthat these disfluencies are likethe mistakes every child makeswhen he or she is learning anynew skill, like walking, writing,or bicycling. Parents should beadvised to accept the disfluencies without any discernable reaction or comment.Particularly concerned parentsmay find it helpful to speak withtheir child in an unhurried way,use shorter, simpler sentences,and ask fewer direct questions.They will also want to arrangetimes the child can talk to them9in a quiet, relaxed environmentwithout outside interference suchas TV, phones, or other people.They should not instruct the childto talk more slowly or to say a disfluent word over again. Instead,they should concentrate on calmly listening to what their child issaying during that special time.Counseling Parents of aChild with Mild StutteringParents of the child who has amild stuttering problem shouldbe advised not to show concernor alarm to the child butinstead be as patient listeners asthey can. Their goal is to providea comfortable speaking environment and to minimize the child’sfrustration and embarrassment.Parents are usually upsetwhen their child repeats soundsor words, but they should be reassured that these are just slipsand tumbles as the child islearning to match his ability tospeak with the many ideas hewants to express.If the parents let the childknow that repetitive stutteringis acceptable to them, this canhelp the child’s speech and language develop without increasedphysical tension and struggle.

PedBook book 1/9/15 8:11 AM Page 10StutteringCase Example: Jeremy, a child withSevere StutteringJeremy’s speech and language developed more slowlythan that of his older sister. He didn’t start to speak untilhe was two; until then, he would point to what hewanted. When he started to speak, he was difficult tounderstand. Jeremy’s parents often had to ask him torepeat what he had said. His speech became a little clearerat age 3 when he was using 2–3 word sentences. But atabout that time he began to repeat initial sounds ofwords and soon he was prolonging sounds and openinghis mouth extra wide when he couldn’t get soundsstarted. Jeremy’s cousin had also been late indeveloping speech, but never stuttered, so Jeremy’sparents assumed he would just outgrow it in time.Unfortunately, the stuttering worsened. Soon Jeremywas saying “um” several times just before a word to get itstarted, in addition to using facial grimaces and widemouth postures when he got stuck. When he madeseveral attempts to get a word started without success,Jeremy would say “Oh, never mind” and give up. He wasgradually becoming more and more reluctant to talk.By this time, Jeremy’s parents became concernedenough to ask their physician for advice. After talking toJeremy, the physician referred them to a speech-languagepathologist in a local pre-school program. The speechlanguage pathologist soon determined that immediatetreatment was needed and worked with Jeremy and hisfamily in their home for a year with good initial success.Following this, Jeremy entered first grade and was seentwice a week by the school speech clinician and continuesto make good progress. Although he still gets hung up on aword occasionally, his language development is normal andhe participates fully in class and in social situations.They should also be encouragedto talk opening about talking justas they would any other topic.While parents may providemodels of a more relaxed way ofspeaking, they should refrainfrom criticizing, showing an-noyance, or telling the child to“slow down.”It is also important for parentsto provide daily opportunities forone-on-one conversations withthe child in a quiet setting, starting with a “special time” of 5 to1010 minutes.These are times when the childhas chosen the activity and canexperience the feeling of talkingabout anything he or she wants.If the child asks about theproblem, parents should talkabout it matter of factly:“Everyone has difficulty learningto talk. It takes time, and lots ofpeople get stuck. It’s okay; it’s alot like learning to ride a bike.It’s a little bit tricky at first.”The parent may mentioncasually that going slowly cansometimes help or that the childneed not hurry if he seems to beasking for help.If the child’s stuttering persistsfor four to six weeks or more despite these efforts on the parents’part, or if the parents are unableto follow these suggestions, thechild should be referred to aspeech-language pathologist (seelater section on referral).Treatment of the child withmild stuttering may be indirectand focused on creating anenvironment in which the childfeels fairly relaxed about speaking, both at home and in thetreatment setting.If more direct treatment isneeded, the speech-languagepathologist may show the childhow to produce speech moreeasily, without increased physical tension and struggle, so thatstuttering gradually diminishesinto something more like normal speech.4,5,7 Some may chooseto train the parents to workmore directly with the child torecognize those times when thechild is more fluent and increase these times.7,13

PedBook book 1/9/15 8:11 AM Page 11StutteringCounseling Parents of a Childwith Severe StutteringThe child with severe stutteringshould be referred immediatelyto a qualified speech-languagepathologist for an evaluation,further counseling, and directtreatment of the child. Becausesevere stuttering frequentlyseems to develop when a childstruggles or becomes afraid ofor concerned with speaking inresponse to his milder stuttering, anything that helps thechild react less negatively andtake his or her disfluencies instride will be of benefit.Parents should model a slowerrate of speaking. They shouldtry to convey acceptance of thechild regardless of the stutteringby paying attention to what thechild is saying rather than to thestuttering. The speech-languagepathologist working with thechild might also encourage theparents to nod or comment onthe child’s courage for “hangingin there,” when the child has aparticularly hard time on aword. In addition, the child withsevere stuttering would benefitfrom being able to share his orher frustration with his or herparents. This may be difficult insome families and may be besthandled with the help of aspeech-language pathologist experienced with the managementof stuttering.Professional treatment of severe stuttering often consists ofhelping the child overcome thefear of stuttering and, at thesame time, teaching the child tospeak, regardless of stuttering,in a slower, more relaxed fash-closely monitor the therapy.3,4,5During a period of a year ormore, the child’s stuttering willoften gradually decrease in frequency and duration. In somecases, the child may recover completely. Treatment results depend on the nature of the child’sproblem, the presence of otherstrengths, the skills of the therapist, and the ability of the familyto provide support.When to Refer to aSpeech-LanguagePathologistTake-Home MessageTalk openlyabout stuttering,acknowledging that“sometimes wordsare hard to say.”ion. In addition, treatment is focused on helping the child’s family create an atmosphere of acceptance of stuttering and conducive to ease in speaking.4,5,7,17As mentioned earlier, somespeech-languagepathologistsmay choose to train the parents toprovide some aspects of therapyin the home. Parents will want tokeep careful records of the child’sresponses to treatment the timeswhen the child is fluent, and will11Children with severe stutteringproblems should be referred immediately. Children who havemild stuttering problems thathave not shown marked improvement within six to eight weeks,depending on the child, should also be referred. These childrenshould be given direct treatmentif it is warranted, and theirparents will receive support andguidance, and they will befollowed carefully.Some children with mild problems may receive direct treatment,but it should be carefully plannedso as not to make the child feel apprehensive or self-conscious aboutthe problem. As Table 1 suggests,children with normal disfluency donot need to be referred unless theparents are so concerned that theyneed reassurance about the normalcy of their child’s speech. Theymay also be followed by the speechclinician to provide additionalguidance if needed.Speech-language pathologists

PedBook book 1/9/15 8:11 AM Page 12Stutteringshould have a Certificate ofClinical Competence (CCC-SLP)from the American SpeechLanguage-Hearing Association,and should also be licensed by thestate in which they practice.Certification requires a master’sdegree from an accredited university, a national examination, anda year of supervised internship.Because stuttering is nolonger required as an area inwhich speech-language pathologists must have hands-on experience to obtain their CCC-SLP,you will want to make sure yourefer to a therapist who has hadextensive experience workingwith the disorder.The Stuttering Foundationprovides referrals to qualifiedspeech-language pathologists inmost areas of the country. Theirtoll-free telephone number is800-992-9392 and web site iswww.StutteringHelp.org. Theyalso provide books and DVDsfor parents.ConclusionPediatricians are often the firstprofessionals to whom parentsturn for advice about their child’s

will outgrow it within 6 months. Time since onset Between 75% and 80% of all children who begin stuttering will begin to show improvement with-in 12 to 24 months without speech therapy. If the child has been stut-tering longer than 6 months, or if the stuttering has worsened, he may be less likely to outgrow it on his own. If he has been .