Transcription

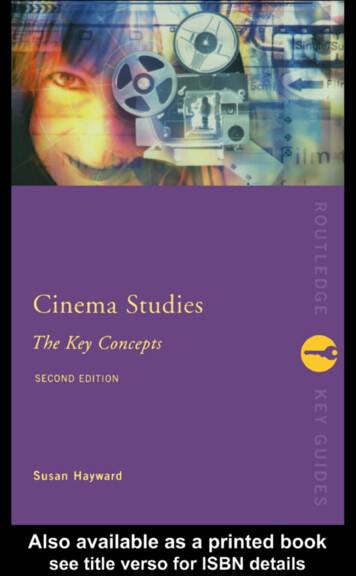

Cinema Studies:The Key ConceptsThis is the essential guide for anyone interested in film. Now in itssecond edition, the text has been completely revised and expanded tomeet the needs of today’s students and film enthusiasts. Some 150 keygenres, movements, theories and production terms are explained andanalysed with depth and clarity. Entries include: auteur theoryBlack CinemaBritish New Wavefeminist film theoryintertextualitymethod actingpornographyThird World CinemaWar filmsA bibliography of essential writings in cinema studies completes anauthoritative yet accessible guide to what is at once a fascinating areaof study and arguably the greatest art form of modern times.Susan Hayward is Professor of French Studies at the University ofExeter. She is the author of French National Cinema (Routledge, 1998)and Luc Besson (MUP, 1998).

Also available from Routledge Key GuidesAncient History: Key Themes and ApproachesNeville MorleyCinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Second edition)Susan HaywardEastern Philosophy: Key ReadingsOliver LeamanFifty Eastern ThinkersDiané CollinsonFifty Contemporary ChoreographersEdited by Martha BremserFifty Key Contemporary ThinkersJohn LechteFifty Key Jewish ThinkersDan Cohn-SherbokFifty Key Thinkers on HistoryMarnie Hughes-WarringtonFifty Key Thinkers in International RelationsMartin GriffithsFifty Major PhilosophersDiané CollinsonKey Concepts in Cultural TheoryAndrew Edgar and Peter SedgwickKey Concepts in Eastern PhilosophyOliver LeamanKey Concepts in Language and LinguisticsR. L. TraskKey Concepts in the Philosophy of EducationJohn Gingell and Christopher WinchKey Concepts in Popular MusicRoy ShukerKey Concepts in Post-Colonial StudiesBill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen TiffinSocial and Cultural Anthropology: The Key ConceptsNigel Rapport and Joanna Overing

Cinema Studies:The Key ConceptsSecond editionSusan HaywardLondon and New York

First published 2000 by Routledge11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EESimultaneously published in the USA and Canadaby Routledge29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis GroupThis edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2001. 2000 Susan HaywardAll rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced orutilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, nowknown or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or inany information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writingfrom the publishersBritish Library Cataloguing in Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British LibraryLibrary of Congress Cataloging in Publication DataA catalogue record for this book has been requestedISBN 0-415-22739-9 (hbk)ISBN 0-415-22740-2 (pbk)ISBN 0-203-12994-6 Master e-book ISBNISBN 0-203-17993-5 (Glassbook Format)

For my students.

CONTENTSPreface to the first ediitionixAcknowledgementsxiList of Key ConceptsKEY CONCEPTSxiii1Bibliography476Index of Films495Name Index505Subject Index517vii

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITIONKey Concepts in Cinema Studies has been two years in the writing. Itis intentionally an in-depth glossary which, it is hoped, will providestudents and teachers of film studies and other persons interested incinema with a useful reference book on key theoretical terms and,where appropriate, the various debates surrounding them. The glossaryalso gives historical overviews of key genres, film theory and filmmovements. Naturally, not ‘everything’ is covered by these entries. Ina later edition further entries may be included, and I would welcomesuggestions of further entries from readers. The present book is basedon my perception of students’ needs when embarking on film studies;its intention is also to give teachers synopses for rapid referencepurposes. Entries have been written as lucidly and as succinctly aspossible, but doubtless there will be some ‘dense’ areas; again Iwelcome feedback. My own students have been very helpful in thisarea.All cross-references are in bold. Sometimes the actual conceptcross-referred may not be the precise form in the entry (for example,ideological in bold actually refers to an entry on ideology).Bibliographical citations at the end of certain entries refer to thebibliography at the end of the book. Wherever it is useful to explain theparticular relevance or direction of a suggested text, this has beendone. Cross-references and bibliographies are given in order ofimportance wherever this seemed significant, otherwise in alphabeticalorder.Finally, instead of a table of contents in traditional style I havesupplied a list of all concepts dealt with in this book. Where a conceptis part of a larger issue, the entry is a cross-reference to the main entrywhere it is discussed (thus, ‘jouissance’ is entered under the ‘J’ entriesix

Preface to the first editionbut as a cross-reference to ‘psychoanalysis’ where it is explained. Atthe beginning of most entries there is a parenthesis suggesting thatyou consult other entries – I believe you will find this dipping acrossuseful and that it will help widen the issue at hand.x

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSMy thanks for the Second Edition extend to Jacqueline Maingard forher help on certain entries (specifically Postcolonial Theory, ThirdCinema, Third World Cinema); to my mother Kathleen Hayward for herassistance on the Bibliography. All other thanks remain the same. Thus,I would like to thank various people who have helped this projectalong. First, Rebecca Barden, my editor, whose unfailing enthusiasmfor the project has made it such an enjoyable book to write. Second,colleagues, students and Routledge readers who put a lot of effort intogiving me feedback on the different entries. Third, I must express mythanks to the British Film Institute for its existence and the extremelyhelpful librarians who made my task that much easier. My thanks forthe First Edition also go to Professor Jennifer Birkett for making timeavailable to complete the project.xi

LIST OF KEY anamorphic lensanimationapparatusart cinemaaspect ratioasynchronization/asynchronous soundaudienceauteur/auteur theory/politique des auteurs/Cahiersdu cinémaavant-gardeBbackstage musical see musicalBlack cinema – UKBlack cinema/Blaxploitation movies – USAB-moviesbody horror films see horror filmsBritish New Wavebuddy filmsxiii

List of key conceptsCCahiers du cinéma group see auteur/auteur theory, FrenchNew Wavecastration/decapitation see psychoanalysiscensorshipcinema nôvocinemascopecinéma-véritéclassclassic canons see codes and conventionsclassic Hollywood cinema/classic narrative cinema/classical narrative cinemacodes and conventions/classic canonscolourcomedyconnotation see denotation/connotationcontent see form/contentcontinuity editingcostume dramascounter-cinema/oppositional cinemacrime thriller, criminal films see film noir, gangster/criminaldetective thriller, private-eye films, thrillercross-cuttingcutDdecapitation see castration/decapitationdeconstructiondeep focus/depth of fielddenotation/connotationdepth of field see deep focusdesire see fantasy, flashbacks, narrative, spectator, stars,subjectivitydetective thriller see gangster egetic/extra- and intra-diegeticdirectordirector of photographydiscoursedisruption/resolutionxiv

List of key arydollying shot see tracking shotdominant/mainstream cinemaEediting/Soviet montageellipsisemblematic shotenunciationepicsEuropean cinemaeyeline matchingexcessexpressionism see German expressionismFfadefantasy/fantasy filmsfemale spectator see spectatorfeminist film theoryfetishism see film noir, voyeurism/fetishismfilm industry see Hollywood, studio systemfilm noirfilm theory see e British CinemaFrench New Wave/Nouvelle VagueFrench poetic realismfuturismGgangster/criminal/detective thriller/private-eye filmsgaze/lookgenderxv

List of key conceptsgenre/sub-genreGerman expressionismGermany/New German cinemagesturalitygothic horror see horrorHHammer horror see horrorHays codehegemonyhistorical films/reconstructionsHollywoodHollywood blacklistHollywood majors see classic Hollywood cinema, studio systemhorror/gothic horror/Hammer horror/horrorthriller/body horror/vampire moviesIiconographyidentification see distanciation, spectator-identificationidentity see psychoanalysis, spectator-identification, dent cinemaintertextualityItalian neo-realismJjouissance see psychoanalysisjump cutLlap dissolve see dissolvelightinglook see gaze/look, imaginary/symbolic, scopophilia, suturexvi

List of key conceptsMmainstream cinema see dominant/mainstream cinemamatchcuttingmediationmelodrama and women’s filmsmetalanguagemetaphor see metonymy/metaphormethod emisrecognition see psychoanalysis, suturemodernismmontage see editing, Soviet uralizingnaturalismneo-realism see Italian neo-realismNew German cinema see Germany/New German cinemaNew Wave/Nouvelle Vague see French New WaveOOedipal trajectory180-degree ruleopposition see narrative, sequencingoppositional cinema see counter-cinemaPparadigmatic/syntagmatic see structuralism/post-structuralismparallel reversalparallel sequencing see editingpatriarchy see Imaginary/Symbolic, Oedipal trajectory,psychoanalysisxvii

List of key conceptsperformance see gesturality, star systemplot/story see classical Hollywood cinema, discourse, narrativepoint of view/subjectivity see subjective camera, subjectivitypolitique des auteurs see auteur, French New Wave, mise-en-scènepornographypostcolonial theorypostmodernismpost-structuralism see structuralism/post-structuralismpreferred readingpresence see absence/presenceprivate-eye films see gangster filmsproducerprojection see apparatus, psychoanalysisprojector see apparatuspsychoanalysispsychological thriller see thrillerQQueer cinemaRrealismreconstructions see historical filmsrepetition/variation/opposition see narration, sequencingrepresentation see feminist film theory, gender, sexuality,stereotypes, subjectivityresistances see avant-garde, counter-cinemareverse-angle shot see shot/reverse-angle shotroad movierules and rule-breaking see counter-cinema, jump cutSscience fiction filmsscopophilia/scopic drive/visual pleasureseamlessnesssemiology/semiotics/sign and iii

List of key conceptsshotsshot/reverse-angle shotsign/signification see semiology/semioticssocial realismsound/soundtrackSoviet cinema/schoolSoviet montage see editing, Soviet cinemaspace and time/spatial and temporal e spectatorstars/star system/star as capital value/star asconstruct/star as deviant/star as cultural value: signand fetish/stargazing and ismstudio systemsubject/objectsubject/subjectivitysubjective camerasurrealismsuturesyntagmatic see paradigmaticTtheoryThird CinemaThird World Cinemas30-degree rulethriller/psychological thrillertime and space see spatial/temporal contiguitytracking shot/travelling shot/dollying shottransitions see cut, dissolves, fade, jump cut, unmatched shots,wipetransparency/transparencetravelling shot see tracking shotUunderground cinemaunmatched shotsxix

List of key conceptsVvampire movies see horror moviesvariation see repetitionvertical integrationviolence see censorship, voyeurism/fetishismvisual pleasure see scopophiliavoyeurism/fetishismWwar filmsWesternswipewomen’s films see melodrama and women’s filmsZzoomxx

Aabsence/presence (see also apparatus) A first definition: cinema makesabsence presence; what is absent is made present. Thus, cinema isabout illusion. It is also about temporal illusion in that the film’snarrative unfolds in the present even though the entire filmic textis prefabricated (the past is made present). Cinema constructs a‘reality’ out of selected images and sounds.This notion of absence/presence applies to character andgender representation within the filmic text and confers a readingon the narrative. For example, an ongoing discourse in a film on acentral character who is actually off-screen implies either a reification(making her or him into an object) or a heroization of that character.Thus, discourses around absent characters played by the youngMarlon Brando, in his 1950s films, position him as object of desire,those around John Wayne as the all-time great American hero. Onthe question of gender-presence, certain genres appear to begender-identified. In the western, women are, to all intents andpurposes, absent. We ‘naturally’ accept this narrative conventionof an exclusively male point of view. But what happens when awestern is centred on a woman, for example Mae West in KlondikeAnnie (Raoul Walsh, 1936) and Joan Crawford in Johnny Guitar(Nicholas Ray, 1954)? Masquerade, mimicry, cross-dressing andgender-bending maybe, but also a transgressive (because it is afemale) point of view – absence made presence.Absence/presence also feeds into nostalgia for former times.This is most clearly exemplified in the viewing of films where thestars are now dead. Obviously, the nostalgia evoked is for differenttypes of ‘realities’ depending on the star yearned after. For example,Marilyn Monroe and James Dean elicit different nostalgia1

absence/presenceresponses from those of Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr. A seconddefinition (see also apparatus, Imaginary/Symbolic,psychoanalysis, suture): film theorists (Baudry, Bellour, Metz,Mulvey (all 1975) making psychoanalytic readings of the dynamicbetween screen and spectator have drawn on Sigmund Freud’sdiscussions of the libido drives and Jacques Lacan’s of the mirrorstage to explain how film works at the unconscious level. The mirrorstage is the moment when the mother holds the child up to themirror and the child imagines an illusory unity with the mother.This is a first moment of identification, with the mother as object.This moment is short-lived, for the child subsequently perceiveseither his difference from or her similarity with the mother. At thispoint the child imagines an illusory identification with the self inthe mirror but then senses the loss of the mother. In Lacanianpsychoanalytic terms this part of the mirror stage is termed theImaginary. The next phase of the mirror stage is termed the Symbolicand can be explained as follows. The child, having sensed the lossof the mother, now desires reunification with her. But this desire issexualized and so the father intervenes. He enters as the third terminto the mirror/reflection, forming a triangle of relationships. Heprohibits access to the mother by saying ‘No’. In this way languagefunctions as the Symbolic order. For the child to become a fullysocialized being/subject, she or he must obey the father’s ‘No’:that is, the ‘Law of the Father’. In so doing, the child enters therealm of language (enters the Symbolic Order): she or he conformsto the Law of the Father which is based in language (the uttered‘No’). The process of socialization for the male child is complete,supposedly, when he finds eventual fulfilment in a female other;the female child, for her part, turns first to her father as object ofdesire and later transfers that desire onto a male other. (For furtherclarification see Imaginary/Symbolic and Oedipal trajectory; andfor a full discussion see Lapsley and Westlake, 1988, 80–90.)By analogy with this psychoanalytic description of the mirrorstage, the screen is defined as the site of the Imaginary: makingabsence presence (bringing into the spectator’s field of visionimages of people or stars who are not in real life present). Thescreen also functions to make presence absence: the spectator isabsent from the screen upon which she or he gazes. However, theinterplay between absence and presence does not end here; if itdid it would end in spectator alienation. Although the spectator isabsent from the screen, she or he becomes presence as the hearing,2

adaptationseeing subject: without that presence the film would have nomeaning. In this respect the screen is seen as having analogieswith the mirror stage. The screen becomes the mirror into which thespectator peers. At first the spectator has a momentaryidentification with that image and sees herself or himself as a unifiedbeing. She or he then perceives her or his difference and becomesaware of the lack, the absence or loss of the mother. Finally, she orhe recognizes herself or himself as perceiving subject. Accordingto this line of analysis, at each film viewing there occurs a reenactment of the unconscious processes involved in the acquisitionof sexual difference (the mirror stage), of language (entry of theSymbolic) and of autonomous selfhood or subjectivity (entry intothe Symbolic order and rupture with the mother as object ofidentification). It is through this interplay of absence/presence thatcinema constructs the spectator as subject of the look andestablishes the desire to look with all that it connotes in terms ofvisual pleasure for the spectator (see gaze). But this visual pleasureis also associated with its opposite: the shame of looking. Absence/presence now functions so as to position the spectator as ‘she orhe who is seeing without being seen’. In this regard, cinema makespossible the re-enactment of the primal scene – that is, accordingto Freud, the moment in a child’s psychological development whenit, unseen, watches its mother and father copulating (seescopophilia, voyeurism/fetishism).A third definition: woman as absence (as object of male desire),man as presence (as perceiving subject). The woman is eternallyfixed as feminine, but not as subject of her own desire. She iseternally fixed and, therefore, mute.For further discussion, see feminist film theory, gaze, scopophilia,spectator-identification.adaptation Literary adaptation to film is a long established tradition incinema starting, for example, with early cinema adaptations of theBible (e.g., the Lumière brothers’ thirteen-scene production of LaVie et passion de Jésus Christ, 1897, and Alice Guy’s La Vie deChrist, 1899). By the 1910s, adaptations of the established literarycanon had become a marketing ploy by which producers andexhibitors could legitimize cinema-going as a venue of ‘taste’ andthus attract the middle classes to their theatres. Literary adaptations3

adaptationgave cinema the respectable cachet of entertainment-as-art. In arelated way, it is noteworthy that literary adaptations haveconsistently been seen to have pedagogical value, that is, teachinga nation (through cinema) about its classics, its literary heritage.Note how in the UK the BBC releases a film, made for screen andsubsequently television viewing, and then issues a teachingpackage (video plus a teacher and student textbook). The choiceof novels adapted has to some extent, therefore, to be seen in thelight of nationalistic ‘value’.A literary adaptation creates a new story, it is not the same asthe original, it takes on a new life, as indeed do the characters.Narrative and characters become independent of the original eventhough both are based – in terms of genesis – on the original. Theadaptation can create stars (in the contemporary UK context, ColinFirth, Pride and Prejudice, 1995, Ewan McGregor, Trainspottiny,1995, Robert Carlyle, The Full Monty, 1997), or stars becomeassociated with that ‘type’ of role (Emma Thompson, HelenaBonham-Carter, Nicole Kidman, Holly Hunter), whereas the novelcreates above all characters we remember and associate with aparticular type of behaviour (e.g. Mrs Bennett, Darcy in Pride andPrejudice). As André Bazin says 1967, 56), film characterizationcreates a whole new mythology existing outside of the originaltext.Essentially there appear to be three types of literary adaptation:first, the more traditionally connoted notion of adaptation, theliterary classic; second, adaptations of plays to screen; and, finally,the adaptation of contemporary texts not yet determined as classicsand possibly bound to remain within the canon of popular fiction.Of these three, arguably, it is the second that remains most faithfulto the original, although contextually it may be updated intocontemporary times, as with several Shakespeare adaptations (forexample, Baz Lurhmann’s Romeo and Juliet, 1996, which is recastinto contemporary Los Angeles). The focus of this entry is primarilyon the first type of adaptation, although mention will be made ofthe third type.Literary adaptations are, within the Western context, perceivedas mostly a European product – almost as if Europe has theestablished literary canon and northern America has not. It shouldbe pointed out, however, that, while this European heritage cinemais the one that predominates and while it represents a deliberatemarketing ploy for exports (Europe sells its culture to the ‘rest of4

adaptationthe world’), the United States does have its own literary classicsthat get adapted – the novels and short stories of Henry James andthose of Edith Wharton spring to mind (e.g., Portrait of a Lady,Jane Campion, 1996; The Age of Innocence, Martin Scorsese, 1993).Jack Clayton’s 1974 version of Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsbyis arguably the benchmark movie of lavish literary adaptationHollywood-style. Modern classics, written by African-Americannovelists, also rank quite highly (e.g., Alice Walker’s The ColorPurple, Spielberg, 1985, and Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Demme,1998). Otherwise, Hollywood is more commonly associated withpopular fiction adaptations (especially detective fiction).In relation to other generic types, critical literature on literaryadaptations is somewhat thin. There appears to have been a surgeof interest during the 1970s (e.g., Bluestone, 1971, Marcus, 1971;Horton and Magretta, 1981; Wagner, 1975) and then again in themid-1980s through the 1990s (e.g. Morrissette, 1985; Friedman, 1993;Marcus 1993; McFarlane 1996; Griffith, 1997). While literaryadaptations have not attracted much analytical attention in thefield of film studies per se, one could speculate that the firstmanifestation of critical writing in the 1970s is linked to theintroduction of film courses into Departments of English andForeign Languages. The fact that the focus of these studies wason questions of fidelity to the original text would tend to supportthis argument. Furthermore, this interest in literary adaptations couldbe read as a reaction to the more difficult branch of film theorybeing practised at that time, namely, structuralism and a bit laterpost-structuralism. The more recent interest appears to correspondto a time when literary adaptations are at their most popular onscreen (particularly in Britain and France).Fidelity criticism, which makes up a great deal of literaryadaptation criticism, focuses on the notion of equivalence. This isa fairly limited approach, however, since it fails to take into accountother levels of meaning. More recently (Andrew, 1984; Marcus,1993) have stressed the importance of examining the ‘value’ of thealterations from text to text. For example, films are more marked byeconomic considerations than the novel and this constitutes amajor reason why the adaptation is not like the novel. Furthermore,it is clear that the choice of stars will impact on the way the originaltext is interpreted; adaptations will cut sections of the novel thatare deemed un-cinematographic or of no interest to the viewers. Inother words, there is always a motivation behind the choices made.5

adaptationMarcus (ibid.) and Monk (1996, 50–1) have pointed to the need fora third level criticism: that is, to see the adaptation within a historicaland semiotic context. Thus, it is not sufficient to show, throughfidelity criticism, the difference between the texts, nor does it sufficeto do a textual analysis based on a demonstration of how the filmrenders (or not) the language and style of the original throughmise-en-scène, editing techniques, the symbolic use of imagesand, finally, the sound-track and music. We need to understand themeaning of these differences within a socio-political, economicand historical context. We need to understand the signs ofdifference. Adaptations are a synergy between the desire forsameness and reproduction on the one hand, and, on the other, theacknowledgement of difference. To a degree they are based onelision and deliberate lack and at the same time in the privileging,even to excess, of certain narrative elements or strategies overothers.Film adaptations are both more and less than the original. Morenot just because they are in excess of the written word (throughhaving both image and sound). But more also because they are amise-en-abîme of authorial texts and therefore of productions ofmeaning. To explain: there is the original text (T1), the adapted text(T2), the film text (T3), the director text(s) (T4n), the star text(s) (T5n),the production (con)texts (T6n), and finally the various texts’ ownintertexts (T7n). Such a chain of signifiers makes it clear that thenotion of authorship becomes very dispersed. Thus, quiteevidentially, the film is less because the original author is only oneamong many (we hear complaints from the audience: ‘it’s not whatthe author wrote’). But it is also more because of the density ofnew texts (and textual meanings, purposes and motivations)clustered around the original (again audiences complain: ‘it’s notat all like the book’). Imagine, finally within this context, the effectsof modernizing a classic literary text.Audiences might complain. And yet they go in their droves tosee the classics on screen. Higson (1993, 120) is right to say thatthe replaying or downplaying of the original material is at leastmatched by if not superseded by the ‘pleasures of pictorialism’.Our pleasure is deeper than our pained expressions at the end ofthe film. Strong (1999, 61) usefully invokes the term ‘neutering’.Although he uses it in a somewhat more specific context – namely,when the adaptive process alters the original’s rendering of theirown time – essentially this effect of neutering and appropriation of6

adaptationa text is a basic practice of adaptation. To a greater or lesser degree,the adaptation neuters the original interest (or a part of the novelist’sintention) thereby appropriating it so that it ‘makes sense’ withinthe present context (for example, Emma Thompson’s script for AngLee’s Sense and Sensibility, 1995, provides a feminist re-inscriptionof the original Austen novel).Classic adaptations are less than transparent. They materializethe novel into something else and the result is a hybrid affair, amixture of genres. More crucially, a temporal sleight of hand andthus intention occurs. By way of illustration of this point let’s takethe Austen, Forster and Pagnol novels and their subsequentadaptations. These novels were modern texts of their day and setin their time yet they were deeply nostalgic for a lost time in thepast (be it for social, economic values or traditions). A majormotivation of the narrative, then, is a nostalgia for what is no more.A sense of lack, of loss is redolent within the novel. Over time,however, these once modern texts become classic texts enteringthe literary canon. By the time they get to the stage of filmadaptation they are no longer of the present time and so becometransformed into what we know as costume or heritage films. Whatwas present is now of the past. A further shift occurs, however, inour reception of the film. It is nostalgic pleasure we are after, notunderstanding. Thus our focus shifts from a desire to know thetimes the novel is referring to in socio-economic or political terms,to a desire to see the times (in terms of costume and décor). Thusthe earlier intention of the narrative – a nostalgia for a past – isneutered. What drives us, the audience, is a nostalgia for the presenttimes of the novel, the lived moment of Austen’s heroines, orPagnol’s and Forster’s characters – our ‘imagined’ past, not that ofthe original text for which that present time represents unwantedchange. Both the novel and the film are looking backwardsnostalgically, but not at the same past.Production values tend to match the perceived value of theoriginal text. Thus, literary classics have high production valuesand the aim is for an authentic re-creation of the past throughappropriate setting, quality mise-en-scène, minute attention to décorand costume, and for star vehicles to embody the main roles.Audience expectation is such that demand for authenticity andtaste is carefully respected. Popular fiction adaptations make nosuch demands of taste. Sets can be flimsy, actors unknown, thewhole purpose here is for cost-effectiveness. A small budget7

adaptationtherefore means low production values. It does not necessarilymean, however, a loss of value. Indeed, many of the 1930s’ and1940s’ Hollywood B-movies have gained such value that they haveentered the Western cinematic canon. Nor have contemporaryliterary adaptations, while inexpensively produced, been withoutimpact in the evolution of film history. The British New Wave ofthe 1960s, for example, relied heavily on contemporary texts fortheir source of inspiration and produced a grainy socio-realism(closely aligned with kitchen-sink drama) which mainly focused onthe socio-economic crises of young working-class males. The socalled New Scottish cinema also draws on modern literary sourcesand provides low-budget movies with a raw realism of economicdeprivation that mostly, but not exclusively, concerns the youngmale in crisis and the drug culture of contemporary Glaswegianyouth (particularly male youth). The adaptation of Irvine Welsh’snovel Trai

War films A bibliography of essential writings in cinema studies completes an . Key Concepts in Cinema Studies has been two years in the writing. It is intentionally an in-depth glossary which, it is hoped, will provide students and