Transcription

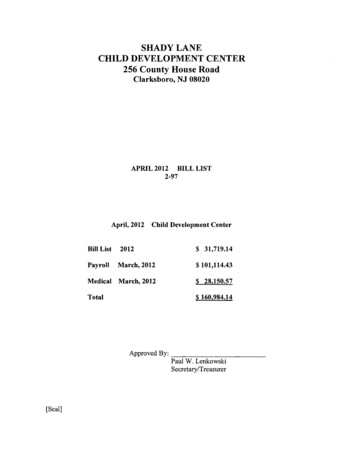

Child developmentIs my child normal?Frank OberklaidKim DreverMilestones and red flags for referralBackgroundDevelopmental problems in young children are commonand have lifelong implications for health and wellbeing.Early detection of developmental problems providesan opportunity for early intervention to shift a child’sdevelopmental trajectory and optimise their potential.ObjectiveThis article describes and recommends a broader conceptof developmental surveillance that should replace thereliance on traditional methods of early detection suchas milestone checklists, parent recall, developmentalscreening tests and clinical judgment.DiscussionGeneral practitioners and other professionals in regularcontact with children and their families are ideally placedto monitor a child’s development, detect problems earlyand to intervene to optimise the child’s developmentand thus promote long term health and wellbeing.Developmental surveillance involves eliciting parentalconcerns, performing skilled observations of the child, andproviding guidance on health and development issuesthat are relevant to the child’s age and the parents’ needs.Standardised tools are available to assist GPs to elicitparental concerns and guide clinical decision making.Keywords: child development; general practice; childhealth services; developmental disabilities/screeningDevelopmental problems in young children are morecommon than generally realised. Surveys suggest thatup to 15% of children under the age of 5 years mayhave difficulties in one or more areas of development,including speech and language, motor, social-emotionaland cognitive.1 At the more severe end of the spectrum,developmental delay and disability will usually bedetected at a relatively early stage, either because thechild has a significant delay that is detected by parentsand/or a health professional, or because they are highrisk (eg. prematurity) and are monitored in a follow upneonatal intensive care unit program.However, many children with mild to moderate problems are notdetected until they are enrolled in structured educational settingssuch as kindergarten or school. In 2009, data collected nationwideon the developmental status of children entering their first year ofschool using the Australian Early Development Index (AEDI) indicatethat up to 24% of children have developmental vulnerabilities inone or more areas.2 Parents are often the first to suspect a delay indevelopment and will seek reassurance from a general practitioneror other health professional.In order to address this often challenging clinical scenario, GPsneed to have an understanding of normal development, a strategyto detect the likelihood of problems, and a network of professionalsto whom children can be referred when necessary and appropriate.Normal developmentDevelopment in children progresses along pathways that arepredictable, with specific observable developmental milestonesachieved at certain ages (Table 1).3 However, there is considerableindividual variability, so that a delay in achieving a particularmilestone is not necessarily significant. However, the level ofconcern rises if the child is late in achieving several milestones.Risk factors to normal developmentBiological and environmental factors impact on the child’sdevelopment. Biological factors include prematurity and low birthweight, birth injury, vision and hearing impairment or chronicillness. Environmental risk factors can be in the immediate family666 Reprinted from Australian Family Physician Vol. 40, No. 9, SEPTEMBER 2011

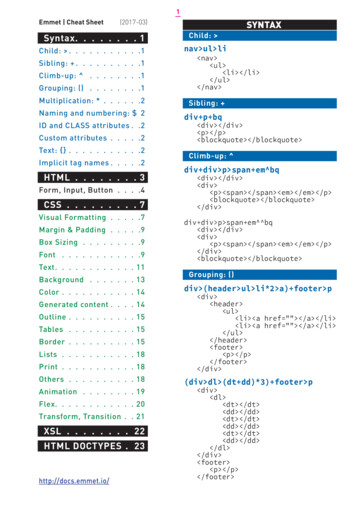

Table 1. Childhood milestones 0–5 years(low parental education, parental mental illness, social isolation,poverty and its consequences), and/or in the community (poorhousing, poor quality services, lack of access to services). Oftenrisk factors cluster together, for example, poverty and its frequentassociations with family and environmental risk factors (whichrepresents the highest identifiable association with mild to moderatedevelopmental delay).Communication and languagemilestonesAverage ageSocial smile6 weeksCooing3 monthsTurns to voice4 monthsBabbles6–9 months‘Mamma’/’Dadda’ (no meaning)8–9 months‘Mamma’/’Dadda’ (with meaning)10–18 monthsUnderstands several words1 yearSpeaks single words12–15 monthsPoints to body parts14–22 monthsAble to name one body part18 monthsParental concernCombines two words14–24 monthsSpeaks six or more words12–20 monthsAble to name five body parts2 yearsHas 50 word vocabulary2 yearsUses pronouns (me, you, I)2 yearsDevelopmental milestones(tasks)Average ageFollows eyes past the midline6 weeksSmiles6 weeksBears weight on legs with support3–7 monthsSits with support4–6 monthsSits without support5–8 monthsBecause parents spend the most time with their children and seethem under different circumstances, they can be expected to be themost reliable observers of their children’s skills. Indeed, there isconsiderable evidence that where parents have concerns about thechild’s development, there is a reasonably high likelihood that thechild will be identified as having problems following assessment.4It follows that health professionals should never ignore parentalconcerns. On the other hand, lack of parental concern about a child’sdevelopment may not mean that the child’s development is normal.Parents’ recall of developmental milestones is often inaccurateand biased toward the normal.5 They tend to be more accurate whenthere is significant developmental delay present.Crawls6–9 monthsPuts everything into mouth4–8 monthsPulls to standing position6–10 monthsFirst tooth6–9 monthsWalks holding on7–13 monthsDrinks from cup10–15 monthsWaves goodbye8–12 monthsClimb stairs14–20 monthsTurns pages2 yearsScribbles1–2 yearsUses a spoon14–24 monthsPuts on clothing21–26 monthsButtons up30–42 monthsJumps on spot20–30 monthsRides a tricycle21–36 monthsBowel control18 months – 4 yearsBladder control (day)8 months – 4 yearsClear hand preference2–5 yearsAdapted with permission Oberklaid F, Kaminsky L. Yourchild’s health. Revised 4th edn. Melbourne: Hardie GrantBooks, 2006Methods of early detectionThere are a number of approaches to the early detection ofdevelopmental problems; these are not necessarily mutuallyexclusive, and most practitioners will often use a combination ofmethods.Milestone checklistsMany professionals use milestone checklists as an aide memoire.Parents especially are reassured when their child’s developmentcorresponds with developmental checklists (Table 1), which can befound in many parenting books. Although development is generallypredictable, it is sometimes uneven, so a child developing normallymay nevertheless be delayed in one or more milestones at aparticular point in time but will subsequently catch up. It is likelythat a reliance on developmental checklists alone will lead to theoveridentification of children with delay. Checklists are best utilisedas an adjunct to early detection.Clinical judgmentAll health professionals rely to a large extent on their clinicaljudgment; informed by their training and clinical experience. It mightbe reasonably assumed that the more experience practitioners have,the more reliable their clinical judgment. While this may hold truefor organic conditions, it has not been shown to be the case in thedetection of developmental problems. A seminal study undertakenmany decades ago showed that paediatricians failed to identifyalmost 50% of children with mental retardation if they relied solelyon clinical judgment.6 Surprisingly, there was little correlationbetween the accuracy of detection and years of experience. WhileReprinted from Australian Family Physician Vol. 40, No. 9, SEPTEMBER 2011 667

FOCUS Is my child normal? Milestones and red flags for referralclinical judgment is an important component of the detection ofdevelopmental problems, we should not rely solely on it.Developmental screening testsDevelopmental screening tests are standardised tools used to ascertaindevelopmental risk or identify problems in children considered to havedifficulties. The Denver Developmental Screening Test (DDST) wastaught to several generations of medical students worldwide and thusbecame the most commonly used developmental screening test. TheDDST has now largely been replaced by more recent screening tests,which have significantly improved psychometric properties (Table 2).7,8However, all of these instruments have relatively low sensitivity,ie. they will miss significant numbers of children who are likely to haveproblems, and low specificity, ie. they will incorrectly identify childrenwhose development is normal. It should be remembered that a screeningtest is not diagnostic – rather it is designed to identify those childrenwho probably have developmental delay from those who probably do not.Development is a dynamic, complex process characterisedby spurts, plateaus and regression. It follows that a snapshot ofdevelopment at a single point in time, obtained by a developmentalscreening test, is unlikely to provide reliable information about a child’sdevelopmental trajectory.Developmental surveillanceThis is a much broader concept than developmental screening. It isa longitudinal process that relies on repeated purposeful review ofthe child and family. Developmental surveillance aims to not onlydetect delays early, but also identify and intervene into risk factorsfor child development.9 It involves eliciting any parental concerns,performing skilled observations of children, and offering parentsinformation and guidance on health and developmental issuesrelevant to the child’s age and parents’ needs.10 The administrationof a formal developmental screening test can be part of surveillance,but the results are interpreted in the context of all the activitiesdescribed above. Every encounter that the GP has with the child is anopportunity to consider their developmental progress; the monitoringof health and development is integral to primary care clinical practice.Involvement of parents – parentquestionnairesThe active participation of parents has been shown to improve theaccuracy of clinical estimates of child development behaviour. Parentalconcerns, when carefully elicited, have been shown to fairly accuratelyidentify developmental, language and behavioural problems.4The Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS)11 is a10-item questionnaire suitable for use between birth and 8 yearsTable 2. Commonly used developmental screening toolsToolDescriptionAge range(months/years)Time toadminister(minutes)AvailabilityAges andStagesQuestionnaire(ASQ)Parent completed age specificquestionnaire; screeningcommunication, gross motor,fine motor, problem solvingand personal adaptive skills;results in pass/fail score foreach domain4–60months10–15Footprint Books Pty Ltdwww.footprint.com.auTelephone 02 9997 3973Fax 02 999 3185Email info@footprint.com.auBriganceScreensDirectly administered toolcomprising nine forms;screening articulation,expressive and receptivelanguage, gross motor, finemotor, general knowledge andpersonal social skills (whereapplicable)For 0–23 months use parentreport0–90months10–15Hawker Brownlow Educationwww.hbe.com.auTelephone 1800 334 603Fax 03 8558 2444ParentsEvaluation ofDevelopmentalStatus (PEDS)Parent interview form;designed to screen fordevelopmental and behavioralproblems needing furtherevaluation; single responseform used for all ages; may beuseful as a surveillance tool0–8 years2–10Centre for Community Child HealthRoyal Children’s Hospital MelbourneTelephone 03 9345 6150Fax 03 9345 5900Email enquiries.ccch@rch.org.auTools for developmental behavioralscreening and surveillancewww.pedstest.com668 Reprinted from Australian Family Physician Vol. 40, No. 9, SEPTEMBER 2011

Is my child normal? Milestones and red flags for referral FOCUSof age (Figure 1). Parental responses to the questions are scoredusing an accompanying scoresheet and categorised into a numberof action pathways (Figure 2). PEDS is particularly attractive tobusy GPs as a way of identifying children who might need furtherassessment or whose parents might benefit from information andguidance. It needs no particular equipment, can be completedbefore or during a consultation, and takes only a few minutes tocomplete and score. (See Resources for more information, includingdetails on purchasing an Australian authorised version of thePEDS.)Assessment conditions associated with high risk of developmental delay:these include chromosomal abnormalities, significant hearingand/or vision problems, dysmorphism, and where there is aclearly abnormal neurological examination high index of suspicion on the basis of observations, failedscreening tests, or major psychosocial/family risk factors major and persistent parental concerns, even in the face ofnormal observation suspicion of autism.Most GPs will already have their networks of specialists andconsultants whom they use. Relationships with these specialists– consultant paediatrician or hospital clinic, speech pathologists,psychologists, occupational therapists – facilitates earlyassessment.Children suspected of having developmental delay need to bereferred for a formal developmental assessment, which is oftenmultidisciplinary. Most commonly, a paediatricianundertakes the initial assessment: reviews thehistory, undertakes a physical and neurologicalexamination, looking for clues as to aetiology,and may then arrange for investigations– chromosomal, chemical, metabolic andneurological – depending on clinical findingsand index of suspicion. Psychologists administerstandardised tests of cognitive functioning,both to ascertain level of functioning and seta baseline to document future developmentalprogress. Other disciplines may be involvedas appropriate, including neurology, speechpathology, occupational therapy, physiotherapy,ophthalmology, social work and genetics.The goal of the assessment is to formulatean accurate developmental profile of theFigure 1. Parents’ Evaluation of Developm

child’s development, there is a reasonably high likelihood that the child will be identified as having problems following assessment.4 It follows that health professionals should never ignore parental concerns. on the other hand, lack of parental concern about a child’s development may not mean that the child’s development is normal.