Transcription

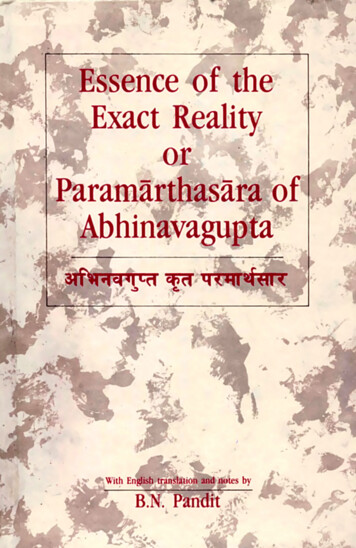

ESSENCE OF THE EXACT REALITY ORPARAMÄRTHASÄRA OF ABHINAVAGUPTA

3T f » R 3 »T*ŤT«c TTlTT«fîtTT3Toafqsft ar qi? aqr re q r ?ď r

Essence o f the Exact RealityorParamarthasara o f Abhinavaguptawith English translation and notes byDr. B N. Panditfriunshiram M an oh arlalP u b lish ers P v t. L td

ISBN 81-215-0523-0First published 1991 1991, Pandit, Baljita NathPublished by Muoshiram M anoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., Post Box 571554 Rani Jhansi Road, New Delhi-110055 and printed at Upasna PrintersShahdara, Delhi-110032.

n to deityI2-3Introductory statementFour spheres (anqias)45The enjoyer6-7One appearing as many8Manifestation of consciousness9Manifestation of Divinity10-11Paramaiiva the Absolute12-13Reflectionary manifestation of diversity14Pure creation15Impure creation16-17Creation of Kaficukas18Removal of Kaficukas19-20Creation of senses and organs21-22Subtle and gross elements23-24Three coverings of consciousness25View based on ignorance26One appearing as many27Diversity an apparent phenomenon28-31Delusion and its two types32Four coverings of Atman33Removal of coverings34Consciousness as the unhidden reality35States of animation36The ever-pure Absolute37Psychic differences between beings38God appearing diverselyDissolution of delusion39-40Dissolution of diversity41-4243Definition of -3434-353536363737-393940404141424242-4343-4444

969798-102103104-105ContentsBrahman the base of everythingInterior creationExterior creationSelf-realizationDissolution of delusion and miseryKarman the cause of rebirthDissolution and ineffectiveness ofkarmanNo rebirth and misery for the purifiedDefinition of liberationLiberation in mortal lifeIneffectiveness of karmanVâsanâ as the cause of rebirthLiberation on the dissolution of VâsanâDeeds without fructificationFreedom from conceptual cognitionNo religious disciplineNon-pollution by sin or pietyCharacter of the liberatedThe Pâsupata vow of a jftâninSatisfaction in perfect unityNo place as pure or impureLiberated even while livingFreedom from upâdhisSituation at the end of lifeRebirth and liberationPsycho-physical behaviour of a jftâninQuick liberationLiberation by stagesDelayed liberation of a Yoga-bhra?laMerits of the knowledge of îealityConclusionGlossary o f Sanskrit 56565757-5858-6161-6262-636363-6464-6565 6666676868-707070-717381

PrefaceKashmir Saivism is a highly perfect school of Indian philosophy,but has remained more or less confined to the valley of Kashmir.Scholars in Indian plains and the South developed interest in it aslate as the present century. The subject is now gaining popularityat some universities in north India as well as in the West. But themain difficulty in the spread of the study of its important works isthe non-availability of an easy textbook that could pave the pathto explore its finer and sophisticated principles and doctrinesdiscussed in some very important works like Sivadfsti, livarapratyabhijiid, Tantraloka etc.It appears that Abhinavagupta, the final authority on KashmirSaivism, must have felt such lacuna in the academic developmentof the subject. Why should he have otherwise taken so muchinterest in recasting and re-editing the Vai navite Paramarthasaraof Patanjali for the purpose of expressing through it most of themain principles of the theistic and monistic absolutism of KashmirSaivism, by the means of an easy and simple method, not overburdened by terse logical arguments and discussions? ThatParamarthasara by Abhinavagupta has been serving students ofKashmir Saivism as an easy textbook of a comprehensive characterfor centuries in the past. Students of Saivism in Kashmir have allalong been using such work as a textbook at the initial step oftheir study in the subject.Paramarthasara of Abhinavagupta, being available only inSanskrit language, could not at present serve the purpose ofcommon man interested in the study of Kashmir Saivism. Itrequired to be brought out in English and Hindi with explanatorynotes for such purpose. The author of the work in hand preparedsuch two editions of the text some years back. But both themanuscripts remained unpublished for all these years for want ofa publisher prepared to invest a good amount for the purpose.Thank God, the director, Munshirara Manoharlal Publishers

viiiPrefacePvt. Ltd. has now taken up the publication of the English editionof Paramarthasara under the title Essence o f the Exact Reality. Itis hoped that the Hindi edition of the work shall also be publishedby the same publisher in the near future.These two editions of Paramarthasara of Abhinavagupta canserve as useful textbooks at the level of M.A. in Sanskrit andPhilosophy at the universities in India and abroad.B.N. PanditJammu Tawi1 January 1991

IntroductionThere are two works on Indian philosophy which are known underthe name Paramarthasara. The earlier one among them is anancient work by AdiSesa. Patafijali is generally known by suchname because it is believed that he was an incarnation of Sesanaga,the famous thousand headed serpent god. Such belief can haverisen out of the fact of his having been the master writer who didmultifarious and extensive academic work as if he had onethousand heads to think and mouths to speak; or it is just possiblethat he may have originally belonged to some Naga-worshippers*sect and may have consequently been called a Naga.Yogaraja the commentator of the later Paramarthasara of Abhinavagupta committed a mistake in taking the Paramarthasara ofSesa as a work belonging to Sarpkhya system. Writers have sincethen been following that view and not even any research scholarsof the present age have bothered to correct the mistake. There isno doubt in the fact that some elements of Samkhya philosophyare present in the work of Sesa, but the elements of Vaisnavitetheism shine more brilliantly in it. Besides, some elements ofSamkhya principles can be found in many other schools of indianphilosophy which are definitely different from the Samkhya school.In fact the Paramarthasara of Se§a is a work of that ancient agein which the ancient theistic Samkhya of sage Kapila, the ancientVaisnavism of Mahabharata and the theistic Vedanta philosophyof Upani§ads were studied as one and single integrated school ofthought with all such elements supporting one another. Suchelements of philosophy had yet to bifurcate and to evolve as somedistinctly separate schools of thought. But, in spite of their suchintegration, the Vaisnavite character of the work* is distinctlypredominant. The Vaisnavism of Patanjali, unlike the philosophyof later Vaispavas, is of monistic view and has absolutism as itsmetaphysical and ontological character. The later Vaisnavismleans towards Vaisnavite mythology but the Vaisnavism of Patan jali maintains its philosophic character. Vallabha advocates a

2Paramarthasara o f Abhinavaguptamonistic view but even he comes closer to mythology and pushesto background the absolutist character of the monistic reality.Therefore his Vttuddhadvaita is different from the advaita of Patanjali which comes closer to the Upani§adic Vedanta. Patanjali’sviews are highly theistic in character and therefore fall apart fromthe Vivariavada of the philosophers in Sankara’s line. Paramarthasara of Patanjali is thus the most ancient philosophic treatise onthe theistic absolutism of Vaisnavitc character.Abhinavagupta, being attracted very much by the style, themethod and the technique of Adisesa, adopted it, made sufficientchanges, additions and alterations in the text of the work andpresented it as a very good textbook of Kashmir Saivism, usefulfor beginners. The language of the work of Abhinavagupta is verysimple and its style is sufficiently lucid and clear. It avoids discus sions on many controversial topics of philosophy and does nottouch the views of any antagonists, but presents, in stead, themainprinciplesofK ashm ir Saivism alone.lt does not resort tothe method of dry logic, but states the principles and doctrinesjn a simple style. Higher philosophic works like Ifvarapratyabhijndand Sivadrsli adopt a method of subtle logic, but Paramdrtliasdraavoids logical discussions. It throws light on all the important andbasic principles of the philosophy of Kashmir Saivism and is thusthe best available textbook to start its study. It is highly helpfulin understanding the works of higher standard like Uvarapratyabhijtla of Utpaladeva.The basic principles of Kashmir Saivism, dealt with in Paratpdrthasara of Abhinavagupta, include those listed below:Metaphysical reality, ontology of Saivism, the theory of the bas\ccausation, the source of the objective creation, the wonderfulnature of the phenomenon, its manifestation in the manner of u.reflection, the process of the evolution of the thirty-six tattvas,the universe as it runs, bondage and its causes, liberation and itsmeans, varieties in liberation, practical paths that lead to it, theposition of an imperfect practitioner, his delayed spiritual evolu tion and so on. It deals thus quite comprehensively with the sub ject and that is its important merit as a textbook.K§emaraja was a disciple of Abhinavagupta. His disciple wasYogaraja, who wrote a detailed commentary on Paramdrthasdra.That commentary explains fully the couplets of Abhinavaguptaand discusses in detail many subtle principles of Kashmir Saivis m.

Introduction3It enhances thus the academic value of the original work asrevised and reconstructed by Abhinavagupta. Such revised, impro ved and explained Paramarthasara of the Saiva author became somuch popular with later academicians that most of them forgotthe more ancient Paramarthasara of AdiSesa. Some grammarianslike NageSa BhaUa do quote the work of Patanjali, but most ofth e later writers on philosophy know only the Paramarthasara ofAbhinavagupta MaheSvarananda, the author of Mahartha-mafijarUpariniala, refers to it as Param arthasara-samgraha. The same hasbeen done by Amj-tananda in his Yoginihfdayadipikd.An English translation of Paramarthasara of Abhinavagupta byL.D. Barnett appeared in the Journal o f the Royal Asiatic Societyin 1910. It was a mere translation without any explanatoiy notes.It did not appear separately as a book and did never become avail able like that.The Sanskrit text of Paramarthasara, along with the detailedcommentary by Yogaraja, was published for the first time in AD1916 at Srinagar under the Kashmir Series of Texts and Studies.Its second edition, along with an additional commentary by ShriD.N. Shastri, was published by Ranviia Kendriya SanskritVidyapeetha, Jammu in 1981. Shri Prabhadevi, a disciple ofSwami Laksmana Joo of Isvara-ashrama, Srinagar, publishedanother edition of the text along with a Hindi commentary on theGita Press style in 1977.Another Hindi edition with detailed explanatory notes, psefulfor M.A. level Indian students, was prepared by the writer of thepresent English translation a few years back. It also will be pub lished as early as possible.The present edition with English translation and notes is inyour hands. The translation is meant to express the sense and thepurport o f the couplets and therefore it is not everywhere astrict literal translation.Both these Hindi and English editions of Paramarthasara ofAbhinavagupta are meant for scholars who want an entrance intothe philosophy of Kashmir Saivism and also into the texts ofhigher standard like livarapratyabhijna and Sivadrjti. Both theseeditions can serve as good textbooks at the M.A. Sanskrit andM.A. Philosophy levels at Indian universities because Paramarthasdra is the best textbook on Kashmir Saivism for beginners. It canadvantageously replace Pratyabhijnahrdaya of Ksemaraja which

4Paramarthasara o f Abhinavaguptahas been occupying such position simply because of its beingavailable with Hindi and English commentaries and also becauseof the non-availability of any good and suitable textbook withtranslation and notes in any of these two languages.Patanjali. mentioning himself as Gonardiya, belonged to theGonda district in U.P. Since he and his associates were a groupof touring scholars, as is evident from Caraka-samhita, they werecalled Carakas or ever travelling scholars. They travelled farand wide from place to place with their leader Punarvasu Atreyafrom institute to institute and belonged thus to the whole of India.Atrigupta, the ancient ancestor of Abhinavagupta, was aninhabitant of the land between Ganga and Yamuna. He wasinvited to Kashmir by king Lalitaditya who provided a land grantand a suitable residential house to him at Pravarasenapura, themodern city of Siinagar, near the §itam umauli temple on thebank of Vitasta (Jehlum). The location of that temple is yet to beascertained. It may become possible to ascertain it if and whencertain Persian works, dealing with the history of Kashmir duringthe period of its quick Muslimization under the rule of SikandarButshikan in the fifteenth century, comes to light.Some old Pandits of Srinagar, who were alive upto the pastdecade, believed that Abhinavagupta lived at his ancestral homeat Gotapora (Guptapura) in the northern outskirts of the old citynear the new colony named Lai Bazar. Places like Guptagangaand Gopitlrtha (Guptatlrtha) on the eastern bank of the Dal lakecan have had some close connection with Abhinavagupta. Amrtavagbhava, a great modern scholar, a successful practitioner o fthe Sambhaxa-yoga of the Trika system and the originator of akind of Neo Saivism in this age, came across a Kashmiri Brah min under the surname ‘Gopya’ at Srinagar in the late twentiesof this century. Besides, he felt the existence of some yoginsbelonging to the line of Abhinavagupta, living at present in divineforms and moving about on the tracts of land near Bahrar on thenorth western side of Nagin lake towards the north of Harlparbat hill.Atrigupta settled at Srinagar in the eighth century A D andAbhinavagupta lived in his human form in the later part of thetenth and the earlier part of the eleventh century. He has recordedthe time of composition in three of his works, namely—Kramas4otra, Bhairavastotra and JixaraprQtyabhijila-xhTti-ximarsinT and the

Introduction5years concerned correspond with AD 990, 992 and 1014 respecti vely.Abhinavagupta was not a ‘Baniva* (VaiSya), as the surnameGupta would suggest in accordance with the present-day usage.His ancestor, Atrigupta was a prdgryajanma, that is, a Brahminof a very high rank. Probably some ancestor of Atrigupta took upthe job of an administrator of one hundied villages and was onthat account designated as a gopta (from Vgoptr) meaning a p ro tector. Such was the usage in ancient ages—1ftani(gopta gramasatadhyaksab). He must have worked on the postso nicely that his family was called by people as Gopta. Theword in its corrupted form changed afterwards into the wordGupta. The great Canakya, known also as Visnugupta and thegreat mathematician Brahmagupta also were such BrahminGoptas whose such name came later to be pronounced as Gupta.Vasugupta and Lak§managupta can have risen in the family ofAtrigupta.As described by the Kerala saint Madhuraja in his Gurunathapardmaria, Abhinavagupta lived like a prince and not like a beg ging monk. As said by Abhinavagupta himself, he did not haveany wife or children—whf* srqjw rji (ajanma dara-sutabandhu-kathamanaptab). But even then he appears to have livedin his ancestral house with his kith and kin. His five cousins werehis disciples. His younger brother; Manorathagupta, was one ofhis pet disciples. Tantraloka was written by him in the house ofanother pet disciple named Mandra whose name has been men tioned by him along with another such disciple Karna in morethan one works. All of them were his close relatives with whomhe lived and worked.In fact Abhinavagupta and such prominent authors of §aivismwho preceded him did not prescribe the path of wandering monksas did the Buddhists, Jains, PaSupatas and Vedantins. Most ofthem lived the lives of pious house holders, followed the Brahmanic ways of life as laid down in dharma-iastras and as come downto them through tradition. They performed all Brahmanic rites butdid not advocate any sort of puritanism. Unlike the Buddhists andJains, they did neither disown nor disturb the traditional Brahmanicreligion. They recommended it and in addition prescribed someTantric methods of sddhand for the sake of quick attainment of the liberation of the highest type from all bondages. The liberation

6Paramarthasara o f Abhinavaguptaattainable through other paths like those of Buddhists, Jains, Vai flavas and Vedantins was taken by them as a thinner bondage ofvarious types. Most of such states of animation were recognizedby them as different sub-states of life in its sleeping state calledsufupti. The path of such Saiva teachers is the path of Siddhas orperfect saints. The methods of sddhana advocated by them areTantric in character. Such methods are very often quick andunfailing in results and yield absolute unity, tasteful through theblissfulness of the absolute, infinite and ever playful divine poten cy realized as one’s own basic nature. The goal of the life prescri bed by these Saivas is the recognition and direct realization ofabsolute Godhead as one’s own basic nature. It is called Pratyabhijftd and can be attained even while one is yet living in a mortalform. These 3aiva philosophers did not prescribe any hard austeri ties for the purification of the self, nor did they advocate anytorturing practices in Hathayoga. The suppression of emotionsand instincts, forcible control of mind and starvation of senses andorgans have been taken by them as harmful. They advocate somesuch easy and spontaneous practices in Tantric yoga through whicha practitioner realizes intuitively his pure and divine nature andrecognizes finally himself as none other than the Almighty Godhaving playfully taken up the role of a bonded soul. Besides, theytaught a monistic philosophy establishing theistic absolutism.Their view has always been pantheistic in character but theyadvocate absolutism as well and thus their philosophy is differentfrom the pantheism of the West which does not see God as an*absolute reality, lying beyond all phenomena. Their practical pathof theology brought about a compromise between the householdreligion and spiritual sddhana, so that both went on harmoniously.Their sddhana was a beautiful combination of jndna (knowledge)yoga and bhakti. Unlike Vaiwavas, their bhakti did not aim onlyat a union between God and soul, but also such a perfect unitywhere God is felt as one’s real self by a devotee and where He isseen by him as all phenomena. That is the difference betweenunion and unity. Union is a lower state of spiritual progress andr perfect unity is its final state.The ¿aivas of Kashmir did not form any special religious sect,as did the Vtraiaivas of Karnataka. They did not at all disturbthe traditional religion taught By Sm ftis. They advised to followone’s religion and to practise ¿aivayoga, side by side. They did

Introduction7not impose any restrictions based on caste, creed, sex etc. Anyone having devotion for Lord Siva could be initiated in Saivism.Therefore it can be adopted by any one who likes it. His adoptionof Saiva practice shall not disturb his traditional religious prac tices. Importance of devotion makes it very sweet and interesting.It teaches an integral path of a spiritual training of both headand heart through logical knowledge and devotionol theology.Besides, it does not ignore or curb the Vdsands for objectiveenjoyments. A disciple, having such Vdsands, is imparted a specialinitiation called yojanikd which carries him after death to somesuperior existence where he can taste superior objective enjoy ments. From there he is lead to quick or gradual spiritual eleva tion in accordance with his psychic situation. Kashmir Saivismdoes not thus ignore human psychology. Its method is bothlogical and phsycholog»cal. Such philosophy of iSaivism ofKashmir was carried to its climax on both of its sides of theoryand practice by Abhinavagupta, the author of the Saiva Paramdrthasdra.Yogaraja, the commentator of Paramdrthasdra was an inhabi tant of a village named Vitastapurl, the modern Vethavottur orVitastavatara. It is a hamlet situated in the foot of Banihal moun tain below Lower Munda. Vitasta or Jehlum, rising from thespring of Verinag, used to flow by the side of that village andproceed to the downward plane on the back of modern Qazigund. That course of the stream was the downward course ofVitasta and was consequently called Vitastavatara. The hamletby its side, where Vitasta was worshipped, got also such name.The waters of the Verinag spring have now been diverted sincelong to the light side slope but the name Vethavottur is still borneby the stream flowing beneath Qazigund.Yogaraja was a disciple of Ksemaraja who lived or only wroteat Bejbehara (Vijayesvara). Ksemaraja was a disciple of Abhinava gupta and lived in the earlier part of the eleventh century. Yoga raja belonged to the later part of the same century. Ksemaraja isthe only disciple of the great master preceptor who took interestin academic activities. He wrote several commentaries on ancientworks and a few independent works on ¿aivism. But it is a wonderthat he did not take up any important work of Abhinavagupta forwriting a good commentary. Mdlinivijaya-vdrtika is still withouta commentary and so is Tantrasdra. The duty of writing a detailed

8Paramdrthasara o f Abhinavaguptacommentaiy on Tantraloka of Abhinavagupta fell on Jayaratha inthe twelfth century. It appears from the writings of K emarajathat he was over-conscious about his superior intelligence andscholarship and was very keen to make a show of it by finding outnew meanings and by expressing things in a complex way. In hiscommentaries on some important works like Sivasutra he takesgreater interest in quoting passages from various texts andtries less to explain the sense and the words of the ancient texts.So far as his philosophic works like Pratyablujnahrdaya are con cerned, he tried to confuse the doctrines of Kashmir Saivism bypresenting them in a complex form and by combining togetherthe theoretical principles and practical doctrines in order to makehis scholarship and intelligence felt. Besides, he did not try hispen on works containing minute philosophic thought and choseStotras and Agamas instead. This tendency did not permithim to make things clear and to work on the important works ofAbhinavagupta. In addition, he expresses disregard towardsvery great ancient preceptors like Bhatta Kallata for whomAbhinavagupta had immense respect and reverence. It is perhapson such account that the great teacher did not mention his name inany of his available works in which he describes the worth of someof his worthy disciples and simply mentions many of them by name.But it is a great merit in Yogaraja that he does not inherit anyconfusing tendency from Ksemaraja. Modem scholars have so farbeen studying Abhinavagupta and other great teachers throughthe writings of Ksemaraja. But now they can start their study of¡Saivism through the Paramarthasdra of Abhinavagupta and thatwill make a marked difference in their understanding.Kashmir Saivism as a distinct school of monistic Saiva philoso phy and its sadhana of the Trika system were introduced to theValley by Sangamaditya in the eight century A D . He was the six teenth teacher in the line of Tryambakaditya I who, having learntit from sage Durvasas at the Kaila a mountain, gave a new start toits teaching in two lines of disciples, one through his son and theother through his daughter. Sangamaditya appeared in the formerline named Tryambaka-mathikd. The other tradition of its teachingwas known as Ardha-tryambaka-malhikd. It flourished later at theJalandhara-pitha at the modem town of Kangara. The divine scrip tures of the Tryambaka-maihika were revealed to its teachers inthe Valley of Kashmir between Ad 7Q0 and 800. These included

Introduction9Siddha, Malini and Vdmaka (Ndmaka) Tantras which constitute thetrinity of the main Trika scriptures. This Trinity of scriptures gavethe name Trika to the mostly popular practical system of KashmirSaivism of the school of Tr/ambaka. The other important scrip tures of the school are Svacchanda, Netra and the well knownRudraydmala Tantras, Sivasutra, a special type of scriptural work,was revealed to Vasugupta sometime in the beginning of the 9thcentury A D . His chief disciple, Bhalta Kallafa flourished duringthe reign of king Avantivarman in the later part of the ninth cen tury. He is the only author of Saivism who has been praised byKalhana in his Rajatarangini as a siddha descended to earth forthe spiritual uplift of people. (See R T , V-66). The other Saivaauthor who has been mentioned by him by name is Somananda.He had built a Siva temple named Someivara where king Har§adeva took refuge for a day before his death when he was chasedby his enemies. Somananda* s name has been mentioned in connec tion with such event in political history. But it appears that spiri tual attainments of Bhatta Kallata had made him so famous andpopular as to attract the attention and interest of the writer of thatpolitical history of Kashmir. His religio philosophical and acade mic activities made the school of Tryamkala sufficiently popularin the valley. He wrote several works, most of which are knownnow only through references and quotations. His Spandakarikaand Spandavfttiy both known together as Spandasarvasva, are stillavailable. In Tantraioka there is such a quotation from one of hisworks which describes the importance of “duti” and proves thushis mastery over the Kula system of Tantrism as well. Some of hisworks like Sxasxabhaxa-sambodhana and Tattvavicara are knownfrom quotations alone. One of his highly important works wasTattvdrthacintdmani which has been referred to and quoted byseveral authors. He wrote a commentary named Madhuvdhini onSivasutra, but that work has also been lost. His works must havebeen highly mystic in style and character and may have remainedout of the scope of ordinary readers and therefore may not haveearned the interest of copyists and got consequently lost in obli vion. Influence of Kjemaraja, who was prejudiced against him,may also have been a cause of disregard for them in the institu tion in later centuries.Spandakarika was wrongly ascribed by K§emaraja to Vasuguptaand most of the scholars of the present age have been wrongly

10Parcmarthasara o f Abhinaragttptafollowing his opinion in such respect. It appears that some mutualrivalry grew between the teachers in the lines of Vasugupta andSomananda in the time of Ksemaraja. The last couplet no. 53 ofSpandakarika was added to it by the teachers of these two linesin two different versions, one ascribing vaguely the authorshipof Spandakarika to Vasugupta and the other ascribing it clearlyto Bhatta Kallata. That 53rd couplet does not exist in the textsexplained by the ancient commentators, that is, Bhatta Kallatahimself and Ramakantha, one of his younger contemporaries.Kscmaraja emphasized the former view and also tried to criticiseBhatta Kallata. But Ramakantha, having lived during the reign ofAvantivarman, must have been a younger contemporary of BhattaKallata. He must have known him and his works very well. Hisopinion carries thus a far greater weight than that of Ksemarajawho appeared in the eleventh century and who was prejudicedagainst Bhatta Kallata. Ramakantha says in clear terms that thefiftysecond couplet,. (Agadha-sam§ayambodhi. . .)etc., is meant to pay homage to Vasugupta, the preceptor of theauthor of the work in hand, that is, Spandakarika. Thus he doesnot mention Vasugupta as the author of Spandakarika but as theteacher of its author. The text of his work consists of only fiftytwo couplets. The fiftythird couplet is therefore definitely a laterinterpolation.Many great teachers and authors of Saiva monism appeared inKashmir during the reign of king Avantivarman and composedmany works of great importance. Bhatta Pradyumna, a cousin o fBhatta Kallata, composed Tattvagarbha-stotra, a lyric, throw ing light on the principles of Saivism and w'ritten in the mannerbefitting ¿aktism. Somananda, the presiding teacher of the schoolof Tryambaka, wrote Sivadfsti, the first philosophical treatise on3aiva monism. His commentary on ParHtrimSaka is known onlythrough references and quotations. His chief disciple, Utpaladeva,w'rote many important works and commentaries, some of whicharc available but some have been lost. His livara-pratyabhijna isthe most important work on the theoretical side of Saiva monism*His three smaller works, known jointly as Siddhitrayi, formsupplements to his Iivara-pratyabhijila. His commentaries on allthese four works and also on ivadr (i are available in fragments.Some such quotations from his pen arc available, which do notexist in any of his known works, and that points towards the

Introduction11fact of his having written some mote important work or works.He was not only a philosopher but a poet of high merit as well.His Sivastotravali, containing religio-philosophic poetry of highmerit, is still sung popularly in the Valley. Ramakantha, a discipleof Utpaladeva and a younger brother of Muktakana, the courtpoet of King Avantivarman, wrote Spandavivrtti, a detailed com mentary on the Karikd of Bhatta Kallaja and a Saivite commen tary on BltagavadgTta, following the Kashmirian version of thetext. His other works are not available even by name. BhaUaNarayana, the author of Stavacintdmani, a philosophic lyric inpraise of Siva, also belonged to the same period.Bhatta Bhaskara, the seventh teacher in the line of Va

position of an imperfect practitioner, his delayed spiritual evolu tion and so on. It deals thus quite comprehensively with the sub ject and that is its important merit as a textbook. K§emaraja was a disciple of Abhinavagupta. His disciple was Yogaraja, who wrote a detailed commentary on Paramdrthasdra.