Transcription

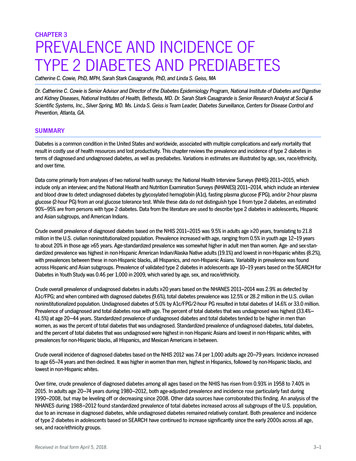

PART 2: GBV DEFINITION,PREVALENCE, AND GLOBALSTATISTICSDefining GBV and showing its prevalence throughglobal statistics raise vital awareness about severalimportant issues: what it is and how to recognize it;the scope of the problem; whom it affects; how itaffects workers and workplace productivity; and itscosts to households and nations.Knowing what constitutes work-related GBV and theurgency of the problem can help economic growthproject implementers, employers, managers, andworkers advocate for reducing GBV and increaseaccountability for safer, more productive workplacesand communities. In the world of work, multiple typesof GBV significantly affect individuals and workplaces,as well as wider economic development objectives.U.S. GOVERNMENT’S DEFINITION OF GBVViolence that is directed at an individual based onhis or her biological sex, gender identity, orperceived adherence to socially defined norms ofmasculinity and femininity. It includes physical,sexual, and psychological abuse; threats; coercion;arbitrary deprivation of liberty; and economicdeprivation, whether occurring in public or privatelife. GBV takes on many forms and can occurthroughout the life cycle. Types of gender-basedviolence can include female infanticide; child sexualabuse; sex trafficking and forced labor; sexualcoercion and abuse; neglect; domestic violence;elder abuse; and harmful traditional practices suchas early and forced marriage, “honor” killings, andfemale genital mutilation/cutting.Specific forms of GBV that impact workers and the workplace include: Domestic and IPV Gender-based workplace discrimination,stigmatization, and social exclusion Sexual harassment and intimidation Sexual exploitation and abuse Trafficking for forced labor and sex work withinand across borders.According to the International Labor Organization(ILO 2011), high-risk groups comprise workers informal and informal economies and include: Office and factory workers Day laborers Dependent family workers Women farmersBoth Women and Men Experience GBVWomen and girls are the most at risk and most affectedby GBV. Consequently, the terms “violence againstwomen” and “gender-based violence” are often usedinterchangeably. But boys and men can also experienceGBV, as can sexual and gender minorities. Regardless ofthe target, GBV is rooted in structural inequalities betweenmen and women and is characterized by the use andabuse of physical, emotional, or financial power andcontrol.Source: 2012. United States Strategy to Prevent and Respondto Gender-based Violence Globally. Washington, DC.Toolkit for Integrating GBV Prevention and Response into Economic Growth Projects3

Child laborers Forced and bonded laborers Migrant workers Domestic workers Health services workers Sex workers.Women are often overrepresented in temporary, lower paying, and lower status jobs with littledecision-making or bargaining power over the terms and conditions of their labor. Risks of work-relatedGBV may be higher in low-wage industries where women workers predominate and hold fewmanagerial positions, such as certain agricultural commodities or garment production. Lack of bargainingpower and labor policies leave millions of workers, particularly women, unprotected and withoutrecourse in the face of gender-based discrimination and workplace violence. Further, workers who donot conform to stereotypical social norms for what a “man” or a “woman” should be or do for theirlivelihood, or who practice diverse gendered behaviors, can become targets of work-relateddiscrimination, stigma, harassment, exploitation, and abuse.In conflict and crisis-affected contexts, forcibly displaced persons—including internally displaced persons(IDP), refugees, and those affected by disasters, famine, or political crisis—face existing and increasedrisks of GBV in their efforts to earn a living. A 2011 United Nations High Commission for Refugees(2011) study of IDP camps in Haiti found that women in all five camps were exploited sexually to obtaincash for basic necessities such as food. “Transactional sex” in situations of crisis and deprivationconstitutes a form of economic, psychological, physical, and sexual GBV. IDP attempting to return topreviously crisis-affected areas for recovery and longer-term development may also be at heightenedrisks of GBV in all spheres of life, including at work.PREVALENCE AND GBV STATISTICSThe global prevalence of GBV is staggering. Women are affected disproportionately. Available statisticsat national, multinational, and global levels set the context and make a compelling case that cannot beignored. Economic growth projects must work to prevent and respond to GBV to ensure that it doesnot undermine economic outcomes and human development.Toolkit for Integrating GBV Prevention and Response into Economic Growth Projects4

GBV PREVALENCE: GLOBAL AND NATIONAL STATISTICS According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 35 percent of women worldwide have experiencedeither physical and/or sexual IPV or non-partner sexual violence (WHO 2013). Violence studies from 86 countries across WHO regions of Africa, the Americas, Eastern Mediterranean,Europe, South-East Asia and the Western Pacific, show that up to 68 percent of women have experiencedphysical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime from an intimate partner (ibid., p. 44). The highest prevalence rates were found in central sub-Saharan Africa, with an estimated up to 66 percent ofever-partnered women having experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner (ibid.). GBV is a major cause of disability and death for women aged 15–44 years (United Nations Women 2011). Globally, one out of every five women will become a victim of rape or attempted rape over the course ofher lifetime (Heise, Ellsberg, and Gottemoeller 1999). Between 20,000 and 50,000 women in Bosnia-Herzegovina were raped during the 1992–1995 war (UNIFEM2002). During the 1994 Rwandan genocide, an estimated 250,000–500,000 women were raped (UN 1996). In 2009, men represented 24 percent of trafficking victims detected globally (United Nations Office on Drugs andCrime 2012). In 2012, women and girls represented 55 percent of the estimated 20.9 million victims of forced laborworldwide, and 98 percent of the estimated 4.5 million forced into sexual exploitation (ILO 2012). Available evidence shows that IPV and non-partner sexual violence are highly prevalent and documentedforms of GBV that women face around the world. IPV and non-partner sexual violence affect workers,workplaces and productivity outside the home, through lost days of work, lost wages, medical expenses,and pain and suffering. Because of the widespread prevalence of IPV and of non-partner sexual violence,and their effects on workers and workplace productivity, several case examples and references in theToolkit relate to forms of IPV or non-partner sexual violence, specifically against women.FORMS OF IPV AND NON-PARTNER SEXUAL VIOLENCE—ALL AFFECT THE WORLD OF WORKIPV refers to any behavior within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological, or sexual harm tothose in the relationship. Non-partner sexual violence refers to any experience of being forced to perform anysexual act that a person did not want to by someone other than his or her partner. All forms of IPV and nonpartner sexual violence affect workers and can take place within the workplace. One of the most prevalentforms in the workplace is sexual harassment.Examples of IPV and non-partner sexual violence that affect the world of work include: Emotional (psychological) abuse, such as sexual harassment, insults, belittling, constant humiliation,intimidation (e.g., destroying things), threats of harm, or threats to take away children; Controlling behaviors, including isolating a person from family and friends; monitoring theirmovements; and restricting access to financial resources, employment, education, or medical care; Acts of physical violence, such as slapping, hitting, kicking, and beating; Sexual violence, including forced sexual intercourse and other forms of sexual coercion.While IPV and non-partner sexual violence prevalence are broadly documented, all forms of GBVremain under-researched in and outside of the world of work. Sexual harassment is a widespread formof workplace GBV, and yet substantial information gaps persist across industries and countries.Toolkit for Integrating GBV Prevention and Response into Economic Growth Projects5

Documentation of GBV in the workplace against men remains an under-researched area as well, and aninformation gap. Data gaps must be addressed on gender-based labor discrimination, stigma, harassment,intimidation, exploitation and abuse, and labor and sex trafficking. More research is needed on all formsof GBV that affect work and the workplace.Recent research and documentation of workplace GBV against women are as eye opening as global GBVSEXUAL HARASSMENT IN THE WORKPLACESexual harassment is a global problem. Between 15 percent and 30 percent of working women questioned insurveys conducted in industrialized countries say they have been subjected to frequent, serious sexualharassment—unwanted touching, pinching, offensive remarks, and unwelcome requests for sexual favors.These offensive and demeaning experiences often result in emotional and physical stress and related illnesses,reducing morale and productivity.“The full picture is incomplete because a large percentage of cases go unreported in every country.” [Dr.Mary] Chinery-Hesse says.Some studies reveal that sexual harassment caused between 6 percent and 8 percent of women surveyed tochange their jobs. According to the ILO, the proportion of one out of 12 women being forced out of a job,after being sexually harassed, could apply to many countries worldwide.Source: ILO. August 1995. re/press-releases/ WCMS 008091/lang-en/index.htmprevalence statistics, which show that women are disproportionately affected. In 2011, the PalestinianCentral Bureau of Statistics worked in partnership with the International Labor Organization (ILO) andthe Institute of Women Studies at Birzeit University to conduct a survey in the occupied Palestinianterritory on GBV in the workplace. The study focused on three types of workplace violence: Gender harassment, Unwanted sexual attention, and Sexual coercion.The survey found that victims of workplace GBV were predominantly young women. Of the 853 womenwho responded to the survey, 29 percent of those aged 25–29, and 18 percent of those aged 24 andunder, reported having experienced one or more of the three forms of violence at work over theprevious 12 months. A further 32 percent of women aged 30–40 interviewed also said they hadexperienced one or more forms of workplace GBV in the last year. Women of all ages are at risk ofGBV in the workplace, whether because of the nature of their jobs or overall social status in society.Sexual harassment and other forms of harassment are serious forms of discrimination across the world that undermine thedignity of women and men, negate gender equality, and can have significant implications. Gender-based violence in theworkplace should be prohibited; policies, programme, legislation and other measures, as appropriate, should be implementedto prevent it. The workplace is a suitable location for prevention through educating women and men about both thediscriminatory nature and the productivity and health impacts of harassment. It should be addressed through social dialogue,including collective bargaining where applicable at the enterprise, sectoral or national level.Source: Report of the Committee on Gender Equality 98th Session of the International Labour ConferenceGeneva, June 2009Toolkit for Integrating GBV Prevention and Response into Economic Growth Projects6

WHY DOES GBV MATTER TO ECONOMIC GROWTH PROJECTS?All forms of GBV affecting the world of work both reflect and reinforce social, economic, and politicalgender inequalities, with unequal outcomes in labor markets and for national economies (Glenn, Melis,and Withers 2009). According to an ILO (2011) report, “[g]ender-based violence not only causes painand suffering but also devastates families, undermines workplace productivity, diminishes nationalcompetitiveness, and stalls development.”A significant proportion of women workers participating in any economic growth project are likely tohave experienced one or more forms of GBV in their lives, in and beyond the world of work. Heise,Ellsberg, and Gottemoeller (2000) estimated that one out of three women has experienced physical,emotional, or sexual violence in an intimate relationship. In 48 population-based surveys from aroundthe world, some 10–69 percent of women reported being physically assaulted by an intimate malepartner at some point in their lives (WHO 2002). It is the case that many women workers manage risksand incidences of IPV, non-partner sexual violence, and all forms of GBV at home and in the workplacesimultaneously.HOW COMMON IS IPV?A growing number of population-based surveys have measured the prevalence of IPV, most notably theWHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic VAW (Heise, Ellsberg, and Gottemoeller1999). The study collected data on IPV from more than 24,000 women in 10 countries, representing diversecultural, geographical, and urban rural settings. It confirmed that IPV is widespread in all its target countries.Among women who had ever been in an intimate partnership: 13–61 percent reported ever having experienced physical violence by a partner 4–49 percent reported having experienced severe physical violence by a partner 6–59 percent reported sexual violence by a partner at some point in their lives 20–75 percent reported experiencing one emotionally abusive act, or more, from a partner in theirlifetime.In addition, a USAID-funded comparative analysis of Demographic and Health Survey data from ninecountries found that the percentage of ever-partnered women who reported experiencing any physical orsexual violence by their current or most recent husband or cohabiting partner ranged from 18 percent inCambodia to 48 percent in Zambia for physical violence, and 4–17 percent for sexual violence. In a 10country analysis of these survey data, physical or sexual IPV reported by currently married women rangedfrom 17 percent in the Dominican Republic to 75 percent in Bangladesh. Similar ranges have beenreported for other multi-country studies.Source: WHO. 2012. Understanding and addressing violence against women. Intimate Partner 77432/1/WHO RHR 12.36 eng.pdf?ua 1Women are often victims of violence at home and at work. GBV does not only originate or recur in thehome, rather it is perpetuated across all systems in which social norms ascribe what is considered correctbehavior for a woman at home, at work, in the community or elsewhere. At work, there are manyaccounts of women not reporting violence at work for fear of stigma and worsening violence perpetratedagainst them in the home or community. Shame, fear of ostracization, isolation, and social norms ofblaming the victim, compound the effects of GBV and contribute to under-reporting, inadequate statistics,and a lack of needed psychological, medical and legal response services for GBV survivors.Toolkit for Integrating GBV Prevention and Response into Economic Growth Projects7

The workplace has become an important site of intervention to reduce GBV and its costly effects not onlyon productivity, but also on individuals, families, and societies. As new forms of paid labor challengestereotypical gender norms related to “women’s” versus “men’s” work, new opportunities for women’seconomic advancement and development open up. This brings both benefits and risks, depending on thecontext and availability of services designed to prevent and respond to GBV. Factors related toglobalization; the rise of insecure, flexible, and temporary forms of labor; deepening economicinequalities; food insecurity; health and political crises; and conflict—all escalate risks and prevalence ofGBV across many contexts.Also in recent decades, the rise in the number of single female-headed households and increasingfeminization of poverty leave many women-headed households among the poorest of the poor (Chant2007). Increased poverty for single female household heads, combined with a lack of adequate laborprotections, heighten their risks of GBV, lost wages, and health problems while further depletingeconomic assets. Single female-headed households often have great caregiving burdens to juggle alongwith being the primary breadwinner. Further, where there are small children, the ill, or the elderly withno earnings, having a single and lesser-paid household head increases risks of economic collapse of theentire household. Taken together, a range of factors heighten risks and costs of GBV amongeconomically, socially, and politically marginalized groups, with domestic VAW being most persistentlywidespread across low-, middle-, and high-income countries and all cultures.In low- and middle-income countries, women’s economic empowerment has had mixed effects on theirrisks of GBV. Women’s secondary school completion and higher education, control over productiveassets, and land ownership have been found to offer some protection. Several studies have forwardedevidence that women’s asset ownership and control may protect them from experiencing IPV (Bhatla,Chakraborty, and Duvvury 2006; Bhatla, Duvvury, and Chakraborty 2011; Jacobs, K. et al, 2011; Kes,Jacobs and Namy 2011; Panda and Agarwal 2005; Swaminathan, Walker, and Rugadya 2008). A 2014mixed methods study in Nicaragua and Tanzania examined women’s land ownership, power in anintimate relationships, and experiences of psychological and physical violence (Grabe, Grose and Dutt2014). The study found that women who owned land exercised greater power in their relationships andwere less likely to experience violence than women who did not own land (ibid.). Further, a Peru landtitling policy innovation in the 1990s helped contribute to women’s economic empowerment andgreater gender equality (Malhotra, A., J. Schulte, P. Patel, and P. Petesch 2009). The policy requiredmandatory joint land titling for married couples, which led to improved employment opportunities andaccess to credit provided by the government (ibid.), which in turn may have improved women’seconomic fallback position and reduced their risks of violence.Women’s increased income generation, greater financial autonomy and asset ownership have shownmixed effects on violence against women. Some studies have found that violence against women mayincrease initially, but then reduce as a result of women’s participation in economic empowermentprograms or groups as household stresses decrease when women’s incomes increase (Schuler et al1996; Hadi 2005). Some research has suggested that women’s involvement in skills training andemployment programs help reduce violence against them, as men see benefits of women’s participation(Ahmed 2005). Women’s economic advancement and asset accumulation can bring either protectiveeffects against IPV and non-partner sexual violence, or increased women’s risks of violence, dependingon contextual factors, such as dominant gender attitudes restricting women’s involvement in paid workor women managing financial and productive resources (Vyas and Watts 2009). Using logistic regressionof adjusted relative risks, a multi-site survey on domestic VAW in India identified gender gaps inToolkit for Integrating GBV Prevention and Response into Economic Growth Projects8

employment, men’s drunkenness, and harassment as risk factors for GBV (International Center forResearch on Women and the Center for Development and Population Activities 2000). Protectivefactors identified included social support, and labor and timesaving appliances in the household (ibid.).It is important to remember the multiple effects of GBV on workers, productivity, and economic growthproject outcomes. Projects can help reduce or unintentionally increase existing or new GBV risks; theycan play a critical role in addressing GBV in and related to the workplace. Any economic growth projectmust take into account the dual effects that GBV can have both on participants and on desired projectoutcomes.COSTS OF GBV TOINDIVIDUALS, HOUSEHOLDS,WORKPLACES, AND NATIONSAll forms of violence are costly and negativelyimpact economic growth and poverty reductionefforts (WHO 2004). Among the many forms ofGBV that affect the workplace and workerproductivity, domestic VAW and IPV have beenthe subject of extensive efforts to measure coststo individuals, households, and nations. Suchstudies have shown that the costs of IPV place anenormous burden on individuals and families,with ripple effects throughout society. Survivors,who are disproportionately women, sufferisolation, inability to work, loss of wages, lack ofparticipation in daily activities, and limited abilityto care for themselves and their dependents.Costs of domestic and workplace-related GBVIn addition to pain and suffering caused by such violence,direct financial costs include those resulting from victims’absenteeism and turnover, illness and accidents, disabilityor even death. Indirect costs include the victims’decreased functionality and performance, quality of work,and timely production. In the case of an organization orcompany, violence at work can include destruction ofproperty; the impact of violence can also negatively affectmotivation and commitment among staff, loyalty to theenterprise, working climate, its public image, and evenopenness to innovation and knowledge building.Source: Di Martino, V. 2002. “Violence at the workplace:The global response,” Africa Newsletter on OccupationalHealth and Safety, Issue 12, p. 5, cited in Gender-basedviolence in the world of work: overview and selectedbibliography. ILO. 2011.Research specifically on the economic costs of VAW has identified four categories of cost: (1) direct andtangible, (2) indirect and tangible, (3) direct and intangible, and (4) indirect and intangible (Table 1).Toolkit for Integrating GBV Prevention and Response into Economic Growth Projects9

TABLE 1. FOUR CATEGORIES OF COSTS OF VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMENDirecttangibleThese costs are actual expenses paid, representing real money spent in response to GBV. Examplesare taxi fare to a hospital and salaries for staff in a safe house or shelter. These costs can beestimated through measuring the goods and services consumed and by multiplying their unit cost.IndirecttangibleThese costs have monetary value in the economy but are measured as a loss of potential. Examplesare lower earnings and profits resulting from reduced productivity. These indirect costs are alsomeasurable, although they involve estimating opportunity costs rather than actual expenditures. Lostpersonal income, for example, can be estimated by measuring lost time at work and multiplying by anappropriate wage rate.DirectintangibleThese costs result directly from a GBV incident but have no monetary value. Examples are pain andsuffering, and the emotional loss of a loved one through a violent death. These costs may beapproximated by quality or value of life measures, although there is some debate as to whether ornot it is appropriate to include these costs when measuring the economic costs of VAW. Those whosupport including direct, intangible costs seek to quantify, for example, the value of child or eldercaregiving that a lost household member may have once provided to support a household memberworking and earning outside the home.IndirectintangibleThese costs result indirectly from GBV, and may have no direct monetary value. Examples are thenegative psychological effects on children who witness GBV. These effects cannot be measured orestimated numerically.Source: Day, T., K. McKenna, and A. Bowlus. 2005. The Economic Costs of Violence Against Women: An Evaluation of the Literature.London, Ontario: United Nations. f%20costs.pdfThe International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) recommended that the costs of VAW andIPV in developing countries need to be collected at household and community levels, and should focuson monetary costs (Duvvury, Grown, and Redner 2004). An ICRW multi-site household survey fundedby USAID on domestic violence in India found that women lost on average seven workdays after anincident of domestic violence (ICRW and the Center for Development and Population Activities 2000,p. 26). The study also found that domestic violence had an impact on a husband’s ability to work, with42 percent of women who reported injury also stated that their husband missed workdays after adomestic violence incident. In terms of income loss from waged work, the average cost per domesticviolence incident per household was Rs759.30. This represents an estimated nearly 100 percent of awoman worker’s average monthly income1 in day-labor households in rural and urban slumcommunities.A study (Siddique 2011) by USAID and CARE Bangladesh found the total cost of domestic VAW inBangladesh—including direct monetary costs to victims, perpetrators, and families, along with costs tothe state and to non-state actors—to be 12.54 percent of the total government budget expenditure and2.10 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In contrast, the Government of Bangladesh’sexpenditure for programs designed to combat VAW for the 2010 fiscal year was only about 0.12percent of total government budget and about 0.02 percent of the estimated GDP for that year (ibid.).Data from this study indicate that the costs of lost workdays, income loss, and increased healthexpenses disproportionately fall upon the shoulders of individuals and families (Table 2). The state,CSOs, and the private sector can and should provide more protective services to prevent and respondto VAW.1, Ibid., p. 26. The study cited women’s average wages at Rs31.7 per day, or Rs 760.80 per month for a six-day workweek.Toolkit for Integrating GBV Prevention and Response into Economic Growth Projects10

TABLE 2. BANGLADESH FY 2010: TOTAL NATIONAL COSTS OF DOMESTIC VAWSocietal levelTotal expenditure budget of the government (%)Percent of GDP (%)Individual and 2.050.020.032.10*Basedon marital domestic violence. †Based on the total cost of VAW.Developing countries are not alone in bearing these enormous costs. Annual costs of IPV have beencalculated at US 5.8 billion in the United States in 20032 and GBP 22.9 billion in England and Wales in2004 (Walby 2004).3 Costs to the Australian national economy have been estimated at AUD 8.1 billion(Access Economics, Ltd. 2004). The UN Secretary General’s 2005 study on VAW estimated that, whencalculated across 13 countries (Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, Chile, Finland, Jamaica, Nicaragua,Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States), monetary costsamounted to US 50 billion per year.The costs of VAW and IPV to nations, households, and individuals are staggering and threaten social andeconomic development aims. It can be extrapolated that, if estimated, the costs of all forms ofworkplace-related GBV only exponentially increase monetary burdens on workers, workplaces, andnational economies. The toll violence takes on women’s health exceeds that of malaria and trafficaccidents combined (United Nations Millennium Project 2005). Costs to nations span healthexpenditures, demands on justice and law enforcement, education systems, and student achievement, aswell as current and future worker income and productivity (United Nations Population Fund 2005).Taken together, compelling evidence from costing studies shows that myriad forms of GBV and VAWcannot be ignored if economic growth projects are to achieve their goals. GBV in and outside the worldof work results in social and economic inequalities worldwide and perpetuates harmful stereotypesabout women’s capacities to fully participate in the workplace.GBV PREVENTION AND RESPONSE ARE VITAL TO ECONOMICGROWTH AND DEVELOPMENTTaken together, evidence on the costs of GBV, combined with research on the beneficial effects ofwomen’s economic advancement, shows that GBV prevention and response are vital to economicgrowth and development at macro- and micro-levels. Recent research from the International MonetaryFund has shown that “there is ample evidence that when women are able to develop their full labormarket potential, there can be significant macroeconomic gains” (Elborgh-Woytek et al. 2013). Data2. Figure includes direct health costs and indirect productivity losses from intimate partner violence based on 1995 annual estimates. SeeNational Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2003. Costs of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in the United States. Atlanta, GA:Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cited in United Nations General Assembly. 2005. “In-depth Study on All Forms of Violence againstWomen: Report of the Secretary-General.” New York, p. 137.3. Figure includes direct and indirect individual, employer, and state expenses related to violence.Toolkit for Integrating GBV Prevention and Response into Economic Growth Projects11

from 2012 from the ILO have enabled researchers to estimate “that of the 865 million womenworldwide who have the potential to contribute more fully to their national economies, 812 million livein emerging and developing nations” (ibid.). Raising female employment to male levels could potentiallyincrease GDP at estimates of between 34 percent (Egypt) and 9 percent (Japan) (Aguirre et al. 2012),and yet GBV unaddressed directly threatens achievement of these projected gains. Efforts to invest inwomen’s economic advanceme

In 2009, men represented 24 percent of trafficking victims detected globally (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2012). In 2012, women and girls represented 55 percent of the estimated 20.9 million victims of forced labor worldwide, and 98 percent of the estimate