Transcription

SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENTIN EARLY ADOLESCENCE:TAPPING INTO THE POWER OF RELATIONSHIPSAND MENTORING2019Delia Hagan, Bernadette Sánchez, Jason Cascarino, Kilian WhiteWith Generous Support from the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThis guide was made possible by the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation. It was enriched bythe generous contributions of the following partners, who provided critical framing, feedback, research, and information that shaped this guide to ensure its accuracy, relevance,and effectiveness.Samantha AlvesMike OmenazuAmy AndersonSam MoultonSam BlombergJenny NagaokaJason CascarinoDarrin PersonDerald DavisMichael RedmonMike Di MarcoDesiree RobertsonAngela DiPesaGene RoehlkepartainBeth FrasterBernadette Sánchez, Ph.D.Michael GarringerElizabeth SantiagoJim GoebelbeckerJo-Ann SchofieldDenise MaroisRobert ShermanGuida MattisonDudney SyllaLydia Monjaras GaytanTorie Weiston-Serdan, Ph.D.Delia HaganJen Vorse WilkaKristin HowardKilian WhiteShaunda LewisJonathan ZaffEmily McCannAnd special thanks to the membersBenita Meltonof the Citizen Schools Middle SchoolMaritere MixYouth Focus GroupWith Generous Support from the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation

TABLE OF CONTENTSSection 1: Introduction1.1: What Is Social and Emotional Learning?. 21.2: Social and Emotional Learning during Early Adolescence. 61.3: Social and Emotional Learning and Relationships. 8Section 2: Literature Review: Relationships, Mentoring, and Social, Emotional,and Academic Development among Young Adolescents2.1: Overview. 102.2: What Social and Emotional Outcomes Are Affected by Relationshipsand Relationship-Based Programs?. 102.3: What Relationship-Based Activities Promote Social and Emotional Outcomes?.162.4: W hat Other Factors Determine Whether Relationship-Based StrategiesAre Successful?.182.5: C haracteristics of Relationship-Based Programs Includedin Literature Review.21Section 3: Case Studies: Four Promising Models3.1: Talking in Circles.243.2: Leaders, Big and Little.293.3: Uniting Nations.353.4: Connecting the Dots. 40Section 4: Recommendations4.1: Researchers. 464.2: School, District, and Youth Development Practitioners.474.3: Policymakers and Funders.51Section 5: Appendix.53

INTRODUCTIONSocial and emotional skills go bymany names — twenty-firstcentury skills, soft skills,non-cognitive skills, and character— just to list a few. Regardless ofwhat we call these skills, orwhether we engage with youth inclassrooms, on the basketball courtor on the school bus, researchand best practices suggest thatstudents’ relationships with peersand caring adults are a key vehiclefor learning critical life skills, suchas teamwork, communication, andcoping with and expressingfeelings.¹ However, many socialand emotional learning programsand initiatives focus more oninstruction and curricula than theydo on relationships and mentoring.Research tells us that anintegrated, intentional approachto social and emotional learningis best,² but without specificinformation about the relationshipbased strategies that best supportstudents’ development, our socialand emotional learning initiativesmay continue to miss criticalopportunities for connectionand growth. This guide sharesspecific information about therelationship-based strategies,including mentoring, that showpromise for cultivating social andemotional learning for youngadolescents, both in school andin out-of-school time settings.What are relationship-basedapproaches? They are practicesthat engage youth in caringrelationships in order to provideopportunities for support, growth,and development. They includeone-to-one mentoring programsthat cultivate individualrelationships between studentsand adult volunteers, and advisorygroups that connect students withpeers and a teacher or adviser toprocess experiences and practicenew skills. They also include groupand peer mentoring programs thatconnect youth with other studentsand caring adults, and can rangefrom structured programs to moreinformal opportunities for youthand adults to connect. And theycan take place during the schoolday, or in an after-school orcommunity-based program.This guide focuses specifically onrelationship-based strategies foryoung adolescents in the middlegrades. Young adolescence is atime of tremendous social andemotional growth,³ yet researchand interventions specific to thisunique developmental stage aresparse compared to those focusingon the elementary grades.⁴ In thewords of Principal MichaelRedmon of Thurston Middle Schoolin Westwood, Massachusetts,“A lot of [social and emotionallearning] work doesn’t focus onthis age group, and this can be themost challenging three years of achild’s life.” Identifyingspecific relationship-basedstrategies that promote social andemotional learning for students inthe middle grades will ensure thatstudents receive the necessarysupports to maximize their socialand emotional learning potentialand lay the foundation for healthydevelopment and relationships asthey grow, increasing their chancesof future academic, career, andlife success.This guide summarizes theexisting research findings abouthow relationships can help fostersocial and emotional developmentfor young adolescents. It providesexamples from the field thatillustrate relationship-basedpractices that can be applied andscaled in schools, after-schoolprograms, and community-basedsettings to enhance opportunitiesfor social and emotional learning.School and district practitioners,as well as youth developmentpractitioners in after-school andcommunity-based settings, canuse this guide to identifypractices that are best suitedfor their communities, as wellas resources to help them applyresearch-based insights in theirwork with young adolescents.Researchers, funders, andpolicymakers can use this guideto identify promising practices,implementation challenges, and1

research gaps that can inform theirexploration of scalable solutions.At the end of this guide, you willfind recommendations based onresearch and practice findingsfor these different audiences.Ultimately, our hope is thatthis guide will help youthdevelopment professionals acrosssettings understand the power ofrelationships to support studentssocially and emotionally, identifypromising practices that can bescaled, and increase access tothese supports for youngadolescents in communitiesacross the United States.1.1 WHAT IS SOCIAL ANDEMOTIONAL LEARNING?Social and emotional learning is acomplex and ongoing process ofdevelopment, spanning childhoodand adulthood, which influencesour ability to understandourselves, manage our emotions,form healthy relationships, andnavigate the environments andcommunities where we learn, work,and play.⁵ But what does this looklike in our everyday lives? Here aresome of the ways young peopleand practitioners have explainedwhat social and emotional learningmeans to them:“It means learning and being kindto each other.” —Ingrid, age 12,Citizen Schools participant,Massachusetts.“To show others how to be agood leader.” —Roodiana, age 12,Citizen Schools participant,Massachusetts.“For me as a mental healthprofessional, leader, and educator,social-emotional learning isessential for our youth to becomeproductive, successful adults.Having the skills to be self-aware,having the ability to selfregulate, be socially aware,develop relationship and conflictmanagement skills, ultimately leadsto one’s ability to make responsibledecisions and maintain effective,healthy relationships. Our youthneed to be taught these skills bybeing in environments where theseskills are modeled by adults andreinforced on a daily basis.”—Molly Ticknor, MA, ATR, LPC,Director of Behavioral Health,Kansas City Public Schools.“To me social and emotionallearning means another way ofteaching individuals how to care,persevere, and to be aware of whothey are and the strengths theypossess.” —Darrin O. Person, Sr.,MSW, Mentoring Manager, FresnoUnified School District.“The great thing about [social andemotional learning] is that itoftentimes happens naturallyduring the time our mentors andstudents spend together. Since ourmentors spend time outsideof school with our students, theyare able to have intentionalconversations that our programstaff may not have the capacityto facilitate with the student. Ourmentors are always asking for toolsto engage with their student ina meaningful way and social andemotional learning provides sucha great framework to provide ourmentors with some tangible waysto help their students continue togrow in these areas in their life. Iam also a mentor to a student andit’s great because I’m able to beaware of how I am doing with myown social and emotional learningand make sure that I am being apositive role model for my studentin this area.” —Audrey Reyes,Manager of Volunteer MentorProgram, Denver Kids.Social and emotional learning isa complex domain of humandevelopment experienceddifferently by people in differentcultural, social, and politicalcontexts, and this has resultedin a complex landscape ofdefinitions, frameworks, andlanguage in the research andpractice fields that surround it.For a summary of the existingresearch literature on social andemotional skills and competencies,and efforts to clarify the varieddefinitions used by researchersand practitioners, see Annex 1.2

However, interdisciplinaryresearch has helped the educationand youth development fieldsto establish some universalknowledge about social andemotional development.Learning involves manyinterconnected areas of the brain.The cognitive, social, emotional,linguistic, and academic domainsof human development are allneurologically linked, so strengthsand weaknesses in one area haveimplications for other areas.⁶As such, skills and competenciesthat are commonly categorizedas social and emotional alsoinvolve cognitive processes,and vice versa.⁷Social and emotional processesand skills are intertwined.Though many social andemotional learning initiativesemphasize a single social oremotional skill — such as gritor growth mindset — researchsuggests that social and emotionalcompetencies are intertwined,and as a result, should beaddressed in comprehensiveand integrated ways rather thanin isolation, alongside academiclearning.⁸Social and emotional learning isprogressive. More complex skillsbuild from more basic skills learnedearlier in life, and different socialand emotional skills becomemore necessary at differentdevelopmental stages.⁹Social and emotional skills areintegral to academic learning.They enable and enhance thelearning process by helpingstudents find meaning in coursematerial and practice, and applyand reflect on their new learningthrough personal connection,emotional processing, and socialinteraction.10Social and emotional learning iscultural and contextual. The wayswe define social and emotionalskills, and the values we place onthese skills, is bound by ourculture — that of our families,racial, ethnic, and religious groups,and the other communities ofwhich we are a part — as well asour contexts (the individualcircumstances, environments, andrelationships we encounter). Thisis especially true as young peopleexplore and seek to define theiridentities, a critical and evolvingsocial and emotional taskthroughout the lifespan.11 Duringyoung adolescence, in particular,identity is highly contextual andrelational, shifting as young peopleform bonds with peers, facerejection, and seek inclusion ingroups. Understanding both theculture young people are broughtup in, as well as the dominantculture of the social, learning, andwork environments they encounteras they grow, is critical tosupporting them effectively.12Additionally, understanding andsupporting young people’sdevelopment of social andemotional skills related to theircultural, ethnic, and racialexperiences, including dealingwith discrimination, coping withracial trauma, and ethnoculturalempathy, is an essentialcomponent of social andemotional development thatis often underemphasized inresearch and practice.13Social and emotional learningis correlated with positivelong-term life outcomes.A strong body of evidence nowdemonstrates that social andemotional learning is correlatedwith academic achievement,college and career success, healthyrelationships, and other positivelife outcomes. Studies show thathigh-quality programming thatfosters social and emotionallearning in schools can improvestudents’ grades, standardizedtest scores, ability to get alongwith others and navigatechallenges, and make healthydecisions.14 Research also indicatesthat social and emotional skillsare correlated with higher ratesof college attendance andgraduation, career success,3

improved mental and physicalhealth, civic engagement, andhealthy relationships withfamily and colleagues.15 In fact,while middle-school grades remainthe strongest single indicator ofcollege readiness, researchindicates that success with twoSEL indicators, motivation, andbehavior may actually have astronger impact on collegereadiness than grades alone.16Furthermore, employers in diversesectors are struggling to findqualified candidates whodemonstrate social andemotional skills related toworkplace success, such asproblems-solving, critical thinking,and communication skills,17 makingthese skills more in demand thanever in our current and futurelabor market.This confluence of research mayexplain why support forintegrated and collaborativeapproaches to social andemotional learning in localcommunities as well as at thefederal level has been growing.18However, equitable access tosocial and emotional learning andsupports is still far from a reality.For more on the growing interestand momentum around social andemotional learning, and persistentissues of inequitable access,see Annex 2.Social and emotional learningopportunities — and students’experiences — are influenceddramatically by historical andsocietal factors.19 Much of thepopular discourse about social andemotional learning focuses on theskills and competencies that youthhave or do not have, creating theperception that youth — and theirability to develop these skills —determine their future prospectsand outcomes. However, historicalevents and societal structures thatinfluence the socioeconomic andlife outcomes of individuals andcommunities, including the UnitedStates’ history of slavery,segregation and racialdiscrimination towardAfrican-American peoples,exploitation and displacementof Native peoples, discriminationtoward and isolation of immigrantand refugee groups, misogyny andhomophobia, and capitalism andits resulting socioeconomicdisparities — from unemploymentto homelessness — shapedeveloping youth’s lives incomplex and intersectingways, facilitating or limitingopportunities for advancementand access to resources based ona student’s race, class, ethnicity,sexuality, and other aspects oftheir identities.20These systemic factors alsoinfluence damaging narrativesthat shape many social andemotional learning efforts. Forexamples, some social andemotional learning initiativestarget low-income students andstudents of color labeled as “highrisk”. Such initiatives reiteratedamaging messages about whichstudents do and do not have socialand emotional assets from whichto build, while overlooking theneed for White students andsocioeconomically privilegedstudents to learn critical social andemotional skills related to power,privilege, and cultural humility.21As we define and understandsocial and emotional skills andcompetencies and considersolutions and interventions, wemust acknowledge the profoundstructural inequities thatinfluence students’ living andlearning environments, andensure that long-standingsystemic barriers areacknowledged and addressed asreadily as students’ immediate,day-to-day social and emotionalneeds.22 For more on partneringwith youth to address systemicinjustice while supporting them innavigating their everyday realities,see Annex 3.4

Social and emotional learningis profoundly influenced by theclimate and culture of students’learning environments. Schoolclimate and culture havesubstantial impacts on students’social and emotional learningoutcomes.23 These systemicfactors, which are shaped by theavailability of supportiverelationships in schools, as wellas the racial, ethnic, cultural, andlinguistic relevance of students’coursework and learningexperiences, can influence whetherstudents feel a sense of belongingin school. Students who feel theybelong in school tend to performbetter academically and reportbetter physical and mentalwellness.24 For more on climate,culture, and belonging, seeAnnex 4.Social and emotional learning isjust as important for adults as it isfor youth. Because social andemotional learning continuesthroughout the lifespan, ongoingdevelopment opportunities foradults, particularly thosepositioned to model these skillsfor youth, are just as essential asprogramming for young people.Thought leaders in the field arebeginning to consider integratedsocial and emotional learningapproaches that includeopportunities to build the capacityof adults in school and after-schoolenvironments — includingteachers, guidance counselors,administrators, cafeteria staff, andvolunteer mentors — to practiceand model the same skills theyhope to cultivate in theirstudents.25 Because students’social and emotional developmentrequires nurturing learningenvironments and relationships,26addressing adult needs andcapacity has become a centralintervention point for promotingpositive student outcomes.Instead of asking, “What skills andcompetencies do students needto achieve social and emotionalwellness?” leaders in thismovement have begun asking,“How can adults in students’learning environments becomethe type of people youth come toprocess emotions, receive support,and take the risks required for theirdevelopment?”Social and emotional learningoccurs in relationship withothers. In order to growsocially and emotionally, youngpeople need healthy, stablelearning environments, completewith healthy relationships, bothinside and outside of school.27As will be explored in the comingsections, young people who havesupportive relationships withcaring adults, and meaningfulrelationships with peers tend tohave more opportunities todevelop socially and emotionally,provided that these relationshipsare developmentally targeted,empowering, and reliable.28Parents, caregivers, and familiesare a critical source of supportiverelationships and opportunities forsocial and emotional learning, butrelationships with caring adultsin students’ schools, recreationalprograms, and communities areessential for their ongoingdevelopment as well.As referenced above, the pastfew years have seen an evolutionin the research, practice, andpolicy fields surrounding socialand emotional learning, whichhave become more precise intheir understanding of humandevelopment and theintersecting, holisticapproaches needed to nurturestudent growth. A growing bodyof research-to-practice insightsand implementationrecommendations are nowavailable to practitioners lookingto integrate social and emotionallearning into their work in schoolsand out-of-school time programs(See Annex 5 for a summary ofthese best practices). However,more research and collaboration isneeded to ensure that social andemotional learning opportunitiesbuild on the assets of youth andcommunities, are inclusive of youth5

identity, context, and culture,address the needs of youth andadults alike, and provide accessto nurturing relationships andlearning environments for allstudents. For a summary ofrecommended next steps forthese fields, see Section 4:Recommendations.1.2 SOCIAL ANDEMOTIONAL LEARNINGDURING EARLYADOLESCENCEA Time of Tremendous ChangeAdolescence is a time oftremendous social and emotionalgrowth for young people, duringwhich they experience some ofthe most significant brain changessince infancy.29 Puberty launchesadolescents into a period ofdramatic physical, hormonal, andbrain changes, which impact theways they view themselves andone another. The development ofemotional processing and rewardstructures in the brain rendersadolescents increasinglysensitive to social feedbackand social status, including cuesabout their social status andappearance.30 The developmentof sexuality during puberty alsocomplicates relationships withpeers and makes adolescentsacutely aware of their ownphysical qualities, withimplications for self-esteem.31For many adolescents, thesechanges can be accompanied byriskier behavior, mood changes,and vulnerability to anxiety anddepression.32Brain imaging studiessubstantiate that the connectionsbetween neurons in the brainincrease rapidly during puberty,followed by a period of “pruning,”or a reduction in these connectionsduring adolescence that allows forthe honing of cognitive,emotional, and social skills.33During early adolescence,capacity for managing emotionand impulses, forward thinking,planning and decision-making,self-awareness and reflection, andunderstanding abstract conceptsexpands, as connections betweenbrain structures involved inexecutive functioning and thoseinvolved in emotional processinggrow stronger.34 During this time,young people build on existingknowledge and self-regulationskills, become more cognitivelyflexible, and grow in their abilityto process more complexinformation, think critically,reflect, and problem solve.35How do young adolescentsdescribe this time in their lives?Middle school students from aCitizen Schools after-schoolprogram in easternMassachusetts described beingtheir age as “hard,” “fun,” “okay,”and “weird.” One student,Roodiana, noted that this is an agewhere she feels adults don’t reallyunderstand her, while Maria sharedthat this age is not fun becausethere’s so much drama in life.Ingrid indicated that being this agecan be stressful sometimes, whileShylah added that it’s stressfulbecause some people say, “Shegot so big!” while others say,“You’re still too young.” Others,like Victor, said that being hisage is simply fun.Amidst all of the cognitive,emotional, and social changesthey are experiencing, youngadolescents are striving to exploreand define their identities. As theyseek to differentiate from parentsand families and secure moreindependence, peer groupsbecome a critical source ofsupport, acceptance, andbelonging.36 In the context ofpeer groups, young teens developintimacy, loyalty, and empathy asthey continue to learn to navigatesocial norms.³⁷ During this time,the avoidance of rejection andsocial isolation becomeparamount, so changes in dressand behavior to “fit in” may becommon. Simultaneously, youngpeople are experiencinggreater day-to-day variationsin their self-esteem, which is6

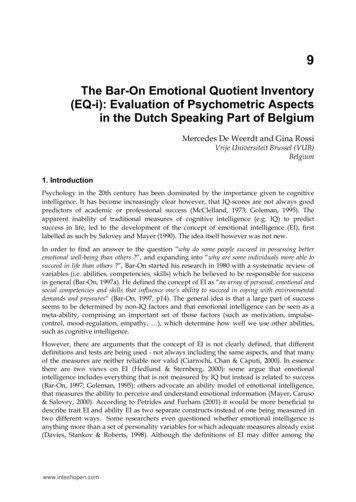

influenced by peer and parentsupport as well as schoolsuccess.³⁸ Having a positive viewof one’s self and the value of one’sefforts to succeed academicallyand socially has implications foryoung adolescents’ developmentof a growth mindset, which canhelp them persist throughadversity and try again when theirinitial efforts don’t work — a keyfactor for navigating the futurechallenges of late adolescenceand adulthood.39Improving Learning Environmentsfor Young AdolescentsTo maximize the potential ofyoung adolescents during this timeof growth, experts recommend50%31%71%69%52%42%providing opportunities for youthto explore their interests, beliefs,and values in safe, supportiveenvironments.40 Relationshipsbetween youth and adults whotake an interest in their strengths,interests, and beliefs providean ideal foundation for thedevelopment of identity andself-confidence. Such relationshipsalso support opportunities toengage in projects that challengeand engage youth personally andlay the groundwork for thedevelopment of agency, critical-thinking, and problem-solving.41Panorama Education and YouthTruth are two organizations thatsupport schools and districts incollecting student data related to“I really feel like a part of myschool’s community.”In your school this year, is there at least one adultwilling to help you with a personal problem?“I know someoneoutside of school whoI can talk to.”“I know some waysto make myself feelbetter or cope with it.”“There is an adult at my school whoI can talk to about it.”“There are programs or services at my schoolthat can help.”Data provided by Youth Truthsocial and emotional learning andother indicators that can informschool improvement, bydeveloping and implementingsurveys that measure indicators ofsocioemotional learning and theirconnections to student outcomes.Both have collected compellingdata that sheds light on theexperiences of middle schoolstudents with regard to schoolclimate, belonging, andrelationships.Youth Truth has surveyed over amillion students across 39 states.From the 215,000 middle schoolstudents who responded to theirsurveys, about 50 percentreported that they felt like a partof their school’s community, butonly 31 percent reported havingat least one adult who would bewilling to help them with apersonal problem. Furthermore,in 32,000 middle school studentswho were asked about supportand social connection in timesof stress, a higher proportion ofstudents reported seeking supportfrom someone outside of school,while a smaller proportion ofstudents found that support froman adult in school or fromprograms or services in school.42Meanwhile, Panorama hascollected data from 3.2 millionstudents across 4,800 schools, and380 districts across the7

n 193,01487.5Belonging76.5This graph showsstudent responsesto Panorama’s Senseof Belonging Scale(scored 1–10) as afunction of their gradelevel and gender.A dramatic drop insense of belongingoccurs between fifthand seventh grade forboth boys and girls.Boys6Girls5.553456789101112Grade LevelUnited States,43 includingresponses to questions such as“How well do people at yourschool understand you as aperson?” and “If you walked out ofclass upset, how concerned wouldyour teacher be?” which measurestudents’ experiences withteacher-student relationships andsense of belonging in school.44The data collected from youngadolescents in the middle gradesreveals that social connectionmatters tremendously at thisdevelopmental stage, but may beharder for students to attain thanat other stages. Young adolescentsin middle school report havingweaker relationships with theirteachers as well as lower ratings oftheir sense of belonging in schoolthan both older and youngerstudents.45 Simultaneously, thecorrelation between theseindicators and student outcomes,including attendance, behavior,and course performance, is muchstronger at this developmentalstage. Just as students arereporting more disconnectionfrom school and adult relationshipsthan ever before, they need themmore than ever before.46 Together,Panorama’s and YouthTruth’s datapoint to a critical gap inpositive youth-adult relationshipsin schools, which intentionalrelationship-based interventionscan help to close.1.3 SOCIAL ANDEMOTIONAL LEARNINGAND RELATIONSHIPSWhile relationships with parentsand caregivers are generallyconsidered the most importantfor young people’s social andemotional development,nonparental adults and peersalso play a critical role, particularlyas students grow and buildrelationships outside of the home.Research suggests that adults andpeers model self-regulation skillsand help young people understandsocial expectations in theircommunities.47The Need for DevelopmentalExperiences and RelationshipsAccording to the University ofChicago Consortium on SchoolResearch’s Foundations for YouthAdult Success Framework,developmental experiences areopportunities for young peopleto process and practice new skillsessential for their development.These experiences are mosteffective when they occur in thecontext of social interactions withadults and peers,48 and can beespecially important for youngpeople’s development of agency,or the confidence and ability totake action to influence theoutcomes of their own lives, asthey experience their own impact8

and value in social contexts.49Relationships with caring adultsthat support young people inreflecting upon, processing,and understanding theirexperiences in

emotional learning for students in the middle grades will ensure that students receive the necessary supports to maximize their social and emotional learning potential and lay the foundation for healthy development and relationships as they grow, increasing their chances of future academic, career,