Transcription

IMPROVING SOCIAL ANDEMOTIONAL LEARNING INPRIMARY SCHOOLSGuidance Report

We would like to thank the many researchers and teachers who provided support and feedback on drafts of this guidance. Inparticular, we would like to thank the Advisory Panel and Evidence Review Team:Advisory Panel: Jonathan Baggaley (PSHE Association), Professor Robin Banerjee (University of Sussex), Professor MargaretBarry (National University of Ireland Galway), Dr Vashti Berry (University of Exeter), Jean Gross CBE (SEAL Community), Emma Lewis(Heathmere Primary School), and Liz Robinson (Big Education).Evidence Review Team: Dr Michael Wigelsworth, Lily Verity, Carla Mason, Professor Neil Humphrey, Professor Pamela Qualter(University of Manchester).Authors: Matthew van Poortvliet (EEF), Dr Aleisha Clarke (EIF), and Jean Gross CBE (SEAL Community).About the Education Endowment FoundationThe Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) is an independent charity supporting teachers and school leaders to use evidence ofwhat works – and what doesn’t – to improve educational outcomes, especially for disadvantaged children and young people.About the Early Intervention FoundationThe Early Intervention Foundation (EIF) is a research charity and What Works centre established in 2013 to champion and support theuse of effective early intervention to improve the lives of children and young people at risk of experiencing poor outcomes.Education Endowment Foundation

CONTENTSForeword2Introduction3What is social and emotional learning (SEL)?4Summary of recommendations8Recommendation 1Teach SEL skills explicitly10Recommendation 2Integrate and model skills through everyday teaching18Recommendation 3Plan carefully for adopting a SEL programme22Recommendation 4Use a ‘SAFE’ curriculum: Sequential, Active,Focused and Explicit26Recommendation 5Reinforce SEL skills through whole-school ethos and activities30Recommendation 6Plan, support, and monitor SEL implementation34References40How this guidance was compiled44Improving social and emotional learning in primary schools1

FOREWORDAsk any primary school teacher, andthey will tell you that alongside the‘core business’ of teaching literacyand numeracy, a large and oftenunrecognised part of their job, involvesaddressing children’s emotional,social and behavioural needs. Withthe right support, children learn toarticulate and manage their emotions,deal with conflict, solve problems,understand things from anotherperson’s perspective, and communicatein appropriate ways. These ‘socialand emotional skills’ are essentialfor children’s development, supporteffective learning, and are linked topositive outcomes in later life.However, many schools feel that there’s little timefor developing such skills, given the pressure toimprove attainment. Although all schools are expectedto deliver Personal, Social, and Health Education(PSHE), it has not been a statutory requirement inthe primary phase and in practice is often squeezedout. Few teachers receive support on how they candevelop social and emotional skills in their mainstreamteaching. This is a missed opportunity because,when carefully implemented, social and emotionallearning can increase positivepupil behaviour, mental healthand well-being, and academic“The evidenceperformance. It is especiallyimportant for children fromsuggests that howdisadvantaged backgrounds, andSEL is adopted andother vulnerable groups, who onaverage have weaker social andembedded reallyemotional skills than their peers.social and emotional development. It provides a startingpoint for schools to review their current approaches,and suggests practical ideas they can implement.Importantly, it argues that such approaches can bewoven into everyday class teaching without creatingburdensome new programmes of work.To arrive at the recommendations, we reviewed thebest available international research and consulted withteachers and other experts. We identified a group ofcore skills and strategies that occur frequently in socialand emotional learning programmes that have goodevidence of impact, and suggest ways of embeddingthese in the classroom and beyond.The international evidence in this area is extensivebut knowledge of how best to implement it in Englishschools is not yet as strong as we would like, soan over-arching recommendation focuses on theimportance of implementing and monitoring progresscarefully, and the requirement for school leaders toprioritise this work if it is to have an impact. Althoughsome schools may feel social and emotional learningis ‘what we do already’, the evidence suggests thathow SEL is adopted and embedded really matters forchildren’s outcomes.As with all our guidance reports, this publication isjust the start. We will now be working with the sector,including through our colleagues in the ResearchSchools Network, to build on the recommendationswith further training, resources, and guidance. And, asever, we will be looking to support and test the mostpromising programmes that put the lessons from theresearch into practice.matters for children’soutcomes.”That is why we have developedthis guidance report. At a timewhen schools are reviewing theircore vision and curriculum offer,and planning to implement statutory Relationships andHealth education, this guidance offers six practical andevidence-based recommendations to support children’s2Sir Kevan CollinsChief ExecutiveEducation Endowment FoundationEducation Endowment Foundation

INTRODUCTIONWhat does this guidance cover?This guidance report aims to help primary schoolssupport children’s social and emotional development.It draws on a recent review of the evidence aboutsocial and emotional learning conducted by theUniversity of Manchester, which was funded by theEducation Endowment Foundation (EEF) and the EarlyIntervention Foundation (EIF). It also draws on a widerbody of evidence and expert input.Currently, most of the evidence regarding Social andEmotional Learning (‘SEL’) is focused on interventionprogrammes with little guidance on the types of strategiesor practices that teachers can integrate into their everydayteaching.* The evidence review aimed to summarise whatis known about the former, and to conduct new analysison the latter, in order that this guidance can providerecommendations on both structured programmes andeveryday teaching practices.In addition to the evidence review, the EEF and EIFcommissioned a survey of what primary schools inEngland are currently doing to support children’ssocial and emotional development. This informationis used to provide context for the recommendations,and to identify where there are gaps between currentpractice and the evidence.More information about the report and how it wasproduced is provided at the end of this guidancereport. Some key references are included for thosewishing to explore the subject in more depth. Thefull evidence review and survey will be publishedseparately, and will contain more comprehensivemethods and reference sections.Who is this guidance for?This guidance is intended for primary schools. It isaimed primarily at senior leaders who are thinkingabout their school’s approach to social and emotionallearning, and at Early Years, Key Stage 1, and KeyStage 2 class teachers. Further audiences who mayfind the guidance relevant include other staff withinschools who are responsible for children’s socialand emotional development (for example, PSHEcoordinators or inclusion leads), local authorities,multi-academy trusts, governors, parents, programmedevelopers, and educational researchers.Acting on the guidanceThe recommendations in this guidance report providea starting point for school leaders to critically reviewhow they support children’s social and emotionaldevelopment. This could include auditing their currentapproach to PSHE or Relationships and Health educationand how it links to classroom teaching, their behaviourmanagement or anti-bullying policies, or their trainingand support for staff. If schools havebought a SEL programme, it mightprompt them to consider if it is aspromising as hoped, and how it might “This guidancebe implemented more effectively—providesor replaced.recommendationsAdditional resources to supporton both structuredthe implementation of theprogrammes andrecommendations made in thiseveryday teachingreport will be developed. The EEF’sguidance report, Putting Evidencepractices.”to Work—A School’s Guide toImplementation, can also supportteachers and senior staff to applythe recommendations in a practical way in their ownschools. The EEF’s other guidance reports, particularlythose on Behaviour, Metacognition, and Working withParents are also relevant, and the EIF Guidebookprovides assessments of evidence-based SELprogrammes.Schools may also want to seek support from the EEF’snational network of Research Schools. ResearchSchools aim to lead the way in the use of evidencebased teaching, building affiliations with large numbersof schools in their region, and supporting the use ofevidence at scale.* By ‘programme’ we mean a structured intervention or curriculum, usually supported by a manual,external training, resources, and timetabled delivery. By ‘practice’ we mean a flexible strategy that can beincorporated into everyday teaching or school life, with few external inputs or formal requirements.Improving social and emotional learning in primary schools3

INTRODUCTIONWhat is Social and Emotional Learning?behaviour management; personal development; andSpiritual, Moral, Social and Cultural Development.Social and Emotional Learning refers to the processthrough which children learn to understand andmanage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feeland show empathy for others, establish and maintainpositive relationships, and make responsible decisions.1There are a range of other terms that schools use thatoverlap with SEL (though have different emphases),including: supporting children’s mental health andwellbeing; character education; development ofchildren’s resilience; bullying prevention; life skills;Throughout this report we refer to ‘SEL’, as definedby the Collaborative for Academic, Social, andEmotional Learning (CASEL), because this definitionis widely used internationally. It consists of five corecompetencies (see Table 1).2 These are skills thathave been linked to a range of positive outcomes,3as explained in more detail in the section below.Table 1: Core Skills at the heart of SELAdapted From - petencyDefinitionAssociated skillsSelfawarenessThe ability to accurately recogniseone’s own emotions, thoughtsand values and how they influencebehaviour. The ability to accuratelyassess one’s strengths and limitationswith a well-grounded sense ofconfidence and optimism. The ability to successfully regulateone’s emotions, thoughts andbehaviours in different situations –effectively managing stress, controllingimpulses, and motivating oneself.The ability to set and work towardspersonal and academic goals. ponsibledecisionmaking4Identifying emotionsAccurate self-perceptionRecognising ResponsibleDecisionMakingImpulse controlStress managementSelf-disciplineSelf-motivationGoal settingOrganisational skillsThe ability to take the perspective of Understanding emotions Empathy/sympathyand empathise with others. The ability Appreciating diversityto understand social and ethical Respect for othersnorms for behaviour and to recognisefamily, school and communitySelf ManagementSelf-Awarenessresources and supports.The ability to successfullyThe ability to accuratelyThe ability to establish and maintainhealthy relationships with diverseindividuals and groups. The abilityto communicate clearly, listenwell, cooperate with others, resistinappropriate social pressure,negotiate conflict constructively andseek and offer help when needed. The ability to make constructivechoices about personal behaviourand social interactions. The realisticevaluation of consequences of variousactions and a consideration of thewellbeing of oneself and others.Identifying emotionsAccurate self-perceptionRecognising strengthsSelf-confidenceSelf-efficacy Identifying problemsAnalysing solutionsSolving problemsEvaluatingReflectingEthical responsibilityasScsrohooFamomCurriculum and Insl c li mily recognise one’s own emotions,thoughts and values and howCommunicationthey influencebehaviour. Theability to accuratelyassessSocial engagementone’s strengthsand limitationsRelationshipbuildingwith a well-grounded sense of Teamworkconfidenceand optimism.Social,Emotional andAcademicLearningtr ua t e, P o li c i e s a n d Pnd Comm u nity P a rt nc tiraconti c eer shipsSocial AwarenessRelationship Skills The ability to take theregulate one’s emotions,perspective of and empathisethoughts and behaviours inwith others. The ability toDiagramadaptedfromsocialCASEL2017different situations– effectivelyunderstandand ethicalmanaging stress, controllingnorms for behaviour and toimpulses, and motivatingrecognise family, school andoneself. The ability to set andcommunity resources andwork towards personal andsupports.academic goals. Impulse controlStress managementSelf-disciplineSelf-motivationGoal settingOrganisational skillsEducation Endowment FoundationsUnderstanding emotionsEmpathy/sympathyAppreciating diversityRespect for othersThe ability to establish andmaintain healthy relationshipwith diverse individuals andgroups. The ability tocommunicate clearly, listenwell, cooperate with othersresist inappropriate socialpressure, negotiate conflictconstructively and seek andoffer help when needed.CommunicationSocial engagementRelationship buildingTeamwork

INTRODUCTIONFigure 1: Evidence reviews including over 700 studies show that on average SEL has a positive impacton academic attainment, equivalent to 4 additional months’ progress.Social and emotional learningModerate impact for moderate cost, based on extensive evidence 4Why do social and emotional skills matter?There is extensive evidence associating childhoodsocial and emotional skills with improved outcomes atschool and in later life, in relation to physical and mentalhealth, school readiness and academic achievement,crime, employment and income.4 For example,longitudinal research in the UK has shown that goodsocial and emotional skills—including self-regulation,self-awareness, and social skills—developed by theage of ten, are predictors of a range of adult outcomes(age 42), such as life satisfaction and wellbeing, labourmarket success, and good overall health.5There is also evidence that children’s skills can beimproved purposefully through school-based SELprogrammes, and that these impacts can persist overtime.6 Numerous large evidence reviews7 indicate that,when well implemented, SEL can have positive impactson a range of outcomes, including: Improved social and emotional skills; improved academic performance (see Figure 1); improved attitudes, behaviour and relationshipsEfforts to promote SEL skills may be especiallyimportant for children from disadvantaged backgrounds,who on average have weaker SEL skills at all agesthan their better off peers.8 This matters for a range ofoutcomes, as lower levels of SEL skills are associatedwith poorer mental health and academic attainment.9There is also evidence to suggest that the benefitsof SEL may extend to teachers and to the schoolenvironment, including a less disruptive and morepositive classroom climate, and teachers reportinglower stress levels, higher job satisfaction, betterrelationships with their children, and higher confidencein their teaching.10 For example, in one survey, 72% ofUK teachers said that teaching SEL had improved theirown relationships with their students.11However, it is important to note that most of theevidence to date is from the US, and how SEL isdelivered is important.12 So, schools should thinkcarefully about how recommended approachesapply to their own contexts. This is discussed in therecommendations that follow.with peers; reduced emotional distress (student depression,anxiety, stress and social withdrawal); reduced levels of bullying; reduced conduct problems; and improved school connection.Improving social and emotional learning in primary schools5

INTRODUCTIONHow does SEL relate to mental health?Social and emotional skills are protective factorsfor mental health. They equip children with thetools and resources to address mental healthchallenges that interfere with life, learning and wellbeing (for example, difficulty regulating emotions,concentrating, and interacting with peers).13 Indeed,recent research has shown that SEL skills at agenine predicted Key Stage 2 test scores at age 11(controlling for prior attainment), via their influence onmental health difficulties in the interim.14However, SEL does not replace the need forcomprehensive systems and services for childrenwith mental health difficulties; rather, SEL providesa foundation that promotes the developmentof competencies in all children and provides aframework to support early intervention and intensiveinterventions for children who need additionaltargeted help.15What does SEL look like in English schools, and how does it relate to PSHE?There are many approaches to developing socialand emotional skills in primary schools, which canrange from taught PSHE lessons, to whole schoolprogrammes, to less intensive practices that teachersintegrate into their everyday teaching. These usuallywork at three levels: whole-school (for example, all-staff training, schoolwide efforts to reduce bullying or improve schoolethos); whole-class (for example, an explicitly taughtweekly classroom curriculum, or integratedstrategies); and targeted (for example, individual or group-basedsupport for children with greater needs).This guidance focuses on whole-school and wholeclass approaches, because targeted approacheswere outside the scope of the review, and are likelyto require more specialist input. Recommendations1–4 particularly focus on the classroom, whilst6Recommendations 5 and 6 focus on the whole school,and implementing change. Schools interested in howSEL may apply to children with Special EducationNeeds and Disabilities (SEND) should look out for EEF’sforthcoming guidance report on SEND.High quality PSHE education will aim to developchildren’s skills whilst also building knowledge aboutparticular aspects of life, for example, physical health orsafety. PSHE can therefore provide valuable contexts inwhich to teach social and emotional learning. However,it is important that: a SEL programme does not simply replace the widerPSHE curriculum; and SEL is not taught as an isolated programme only inPSHE time, without involvement or connection withthe wider staff and school.Education Endowment Foundation

INTRODUCTIONWhat do schools currently say about SEL?A survey of over 400 primary schools conducted by theUniversity of Manchester found that:16 Many schools say that SEL is important: 46% saidthat SEL is their top priority and a further 49% believeit is important alongside a number of other priorities. Nearly half of schools (48%) say that they are devoting‘much more time’ to SEL compared to five years ago,and further third (36%) ‘somewhat more time’, citinghigher needs among children and families, includingchildren ‘struggling to cope’. However, only a third (36%) said that dedicatedplanning for SEL was central to their practice. Schools reported barriers to delivering SEL: time is thenumber one issue (71%), and the pressure to focus onother priorities was also commonly cited (68%). Half of schools (51%) reported that they have specifictime-tabled slots for SEL; the other half did not. Ofthose that did, most spent 30–60 minutes per week onSEL. A separate survey of teachers suggested that lessthan one third have any class time dedicated for SEL.17 School-wide approaches to supporting SEL (such as,school policies, assemblies, or dedicated staff groupswith responsibility for SEL), were considered ‘centralto practice’ in around half of schools (40–60%).These findings suggest several key areas whereschools might benefit from additional support, including:strategies and resources that can support SEL teaching(ideally without requiring large blocks of dedicated time);information on evidence-based programmes and curricula;and ideas for improving whole-school approaches andplanning for SEL, including staff development. Few schools reported using evidence-basedprogrammes; the most commonly cited programmeswere ’dot-b’ mindfulness (27 schools) and FRIENDSfor Life (15 schools). The most commonly used approach among schoolswas SEAL (Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning),which was developed as part of the Primary NationalStrategies. 104 schools said they used SEALresources, and a further 74 that they had used thempreviously. Many schools reported having had some trainingrelated to SEL, but in most cases this appears tohave been a one-off workshop, rather than ongoingsupport. When asked what would help them deliver SEL moreeffectively, schools identified training as the greatestneed. This was followed by the desire for a curriculumand resources on SEL including ‘links to the corecurriculum’ and resources ‘that don’t require hugetime commitments’.The guidance that follows aims to support schools inintegrating high quality SEL throughout the school,considering the priorities and challenges that schoolshave identified.Improving social and emotional learning in primary schools7

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONSTeaching strategies1Teach SEL skills explicitly Use a range of strategiesto teach key skills, both indedicated time, and in everydayteaching. Self-awareness: expandchildren’s emotional vocabularyand support them to expressemotions. Self-regulation: teach children touse self-calming strategies andpositive self-talk to help deal withintense emotions. Social awareness: use storiesto discuss others’ emotions andperspectives. Relationship skills: role play goodcommunication and listeningskills.Curriculum23Integrate and model SELskills through everydayteachingPlan carefully for adopting aSEL programme Model the social and emotionalbehaviours you want children toadopt. Give specific and focused praisewhen children display SEL skills. Do not rely on ‘crisis moments’for teaching skills. Embed SEL teaching across arange of subject areas: literacy,history, drama and PE all providegood opportunities to link toSEL. Use simple ground-rules ingroupwork and classroomdiscussion to reinforce SELskills. Use a planned series of lessonsto teach skills in dedicated time. Adopting an evidence-basedprogramme is likely to be abetter bet than developing yourown from scratch. Explore and prepare carefullybefore adopting a programme—review what is required to deliverit, and whether it is suitable foryour needs and context. Use evidence summaries (suchas those from EIF and EEF) asa quick way of assessing theevidence for programmes. Once underway, regularly reviewprogress, and adapt with care. Responsible decision-making:teach and practise problemsolving strategies.Page 108Page 18Education Endowment FoundationPage 22

Whole-school45Use a SAFE curriculum:Sequential, Active,Focused and ExplicitReinforce SEL skills throughwhole-school ethos andactivitiesImplementation6Plan, support, and monitorSEL implementationSAFE Ensure your curriculum buildsskills sequentially across lessonsand year groups. Start early andthink long term. Establish schoolwide norms,expectations and routines thatsupport children’s social andemotional development. Establish a shared vision forSEL: ensure it is connected torather than competing with otherschool priorities. Balance teacher-led activitieswith active forms of learning,such as: role-play, discussionand small group work, topractise skills. Align your school’s behaviourand anti-bullying policies withSEL. Involve teachers and school staffin planning for SEL. Focus your time: quality mattersmore than quantity. Brief regularinstruction appears moreeffective than infrequent longsessions. Be explicit: clearly identify theskills that are being taught andwhy they are important. Seek ideas and support fromstaff and pupils in how theschool environment can beimproved. Actively engage with parentsto reinforce skills in the homeenvironment. Provide training and supportto all school staff, covering:readiness for change;development of skills andknowledge; and support forembedding change. Prioritise implementationquality: teacher preparednessand enthusiasm for SELare associated with betteroutcomes. Monitor implementation andevaluate the impact of yourapproaches.Page 26Page 30Page 34Improving social and emotional learning in primary schools9

1Teach SEL skillsexplicitlyThis recommendation describes simple activities, routines, and strategies that teachers can use to develop particular socialand emotional skills. Recent research suggests that supporting teachers to develop and use a repertoire of such strategiesis likely to be an efficient way of improving SEL provision without requiring large blocks of dedicated curriculum time.18 Thestrategies in this chapter have been identified from evidence-based programmes, and can be used flexibly: as part of planned time dedicated to SEL; integrated into everyday class teaching; and to complement a more structured programme (see Recommendation 3).Some strategies (e.g. the use of stories) may feel familiar to teachers, but the key element is in making the teaching of SELskills more frequent, purposeful and explicit.19 Some strategies will be easier to align with everyday class teaching; others willfit more naturally into standalone PSHE sessions.The recommendation is focused around the five core SEL skills described in the introduction to this guidance. In each casewe describe what is meant by the skill, why it matters, and strategies and examples that could be used for developing the skill.It is important to note that whilst there is growing research promoting such strategies, and they have been drawn fromevidence-based approaches, they have not been evaluated as standalone strategies, so schools need to judge whichapproaches are suitable for them and are effective in their contexts.A. Strategies to enhance children’s self-awarenessWhat do we mean by self-awareness?Self-awareness is concerned with the ability torecognise our emotions and thoughts, and tounderstand how they influence our behaviour. It alsomeans being aware of our strengths and having abelief in oneself (‘self efficacy’). Good self-awarenessis associated with reduced difficulties in socialfunctioning and fewer externalising problems, inparticular aggression.20 Two areas that teachers cansupport are children’s knowledge of emotions, andability to express emotions.Examples of activities used to develop children’s self-awarenessKnowledge of emotionsTeachers can help children label and recogniseemotions through explicit vocabulary teaching (‘puttingfeelings into words’), and activities that give childrenthe opportunity to practise using this language in realcontexts through games, stories, and other activities.For example: using story books to discuss how characters feeland why;10 using games to develop children’s vocabulary e.g.miming activities where children guess a feeling thatis being portrayed (‘emotional charades’); and using mirrors, photographs and pictures to talkabout what happens to people’s faces and bodieswhen they are experiencing particular emotions:for example, children might match photographsdisplaying different emotions with emotion labelsand scenario labels.Education Endowment Foundation

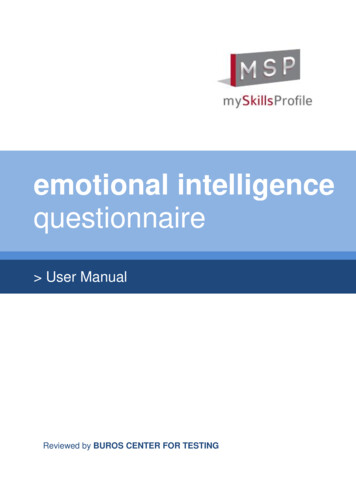

Emotional expressionChildren’s ability to recognise and express emotionscan be supported with a class display, which isregularly referenced (see Box 1). Teachers can alsodevelop children’s ability to tell others how they arefeeling by, for example: explaining to children that all feelings are okay, butthe behaviours they lead to may not be okay. It isokay to feel angry, for example, but not okay to actin ways that hurt others. teaching them to use ‘I’ messages (articulating howyou feel and why): ‘I feel x because ’ providing supportive prompts to children who havedifficulty talking about their emotions, such as: ‘Itlooks like you might be feeling sad, can you tell mewhat happened?’. The simple act of naming theemotion can help children understand it more clearly.Box 1: Feelings displayCreate a ‘feelings display’ in the classroom (forexample, feelings tree with the leaves as differentFeelings wheel: to support explicit teaching andpractice of new vocabularyfeelings words, emoticon board, feelings wheel,poster or dictionary). The teacher can introduce theExcitedthey are feeling when they come into the classroomin the morning, or at the start of the afternoon.21Teachers may also make reference to the display indescribing their own emotions: ‘This is beginning tomake me frustrated, because you’re talking whilst eemotion within the feelings display to indicate howdSachildren place their name or photo on a relevantScemotional expression, for example, by havingeBluwnDo eypMo ssedpreDeTeachers can also use the display to supportntelfill ntedPleasedthink of a time you might feel frustrated?’HaWhat does it mean to feel frustrated? Can youer ‘We have learned a new feelings word today–edart-he ticrmtheWa mpagSyvinLo dKinfeelings tree that you could use?’ndTe ‘You feel happy? Is there another word on ourEnergeticNervousEcstaticBouncyymany ways on an ongoing basis, for example:TenJit setAn eryxiouTerrifi sedvocabulary in the display, and then use the display inAngryam trying to explain something important to you.’Improving social and emo

develop social and emotional skills in their mainstream teaching. This is a missed opportunity because, when carefully implemented, social and emotional learning can increase positive pupil behaviour, mental health and well-being, and academic performance. It is especially i