Transcription

Acute MyeloidLeukaemiamapping the policy response to an acute cancerin France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UKSupported by:

Acute Myeloid Leukaemiamapping the policy response to an acute cancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UKContents2About this report4Executive summary77Chapter 1: Introduction—what is AML?An acute leukaemia7A genetically complex malignancy8Understanding and quantifying the burden in Europe13 Chapter 2: Navigating the healthcare and patient care experience13 Diagnosis and testing for AML20 Mapping the treatment pathway22 Stem cell transplants—only for younger, fitter patients?26 Chapter 3: The costs of AML26 Economic costs of AML27Cost of intensive therapy27Cost of supportive care and less intensive therapy29Indirect costs29 Impact on patients, their families and carers29Side effects of treatment30Fertility preservation: a key consideration for younger patients32Psychosocial support is crucial33Financial impact on patients35 Chapter 4: AML heath policy under the spotlight35 National policy and evidence-based treatment guidelines36 Specialist cancer nurses and the multidisciplinary care team37 Centralised, specialist centres37 Humanising hospitals39 Vaccination of healthcare staff and reducing infections41 Measuring and monitoring AML43 Awareness, advocacy and education: the role of patient groups and expertpatients45 Conclusion The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 20191

2Acute Myeloid Leukaemiamapping the policy response to an acute cancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UKAbout this reportAcute Myeloid Leukaemia: mapping the policy response to an acutecancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK is an EconomistIntelligence Unit report, supported by Amgen, a pharmaceuticalcompany. It considers the healthcare system approaches to themanagement of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), as well as its costs andpatient experience, to make recommendations for policy responsesgoing forward.The research reviews AML care across five European countries andexplores a number of factors that play a part in the development ofhigh-quality services for patients with AML.This report is based on desk-based research and in-depth interviewswith 13 experts drawn from healthcare professionals, patient groups,patients, government organisations and health economists. Ourthanks are due to the following for their time and insights (listedalphabetically): Simone Boselli, public affairs director, EURORDIS (Rare DiseasesEurope) Felicetto Ferrara, chief of Haematology Unit, Cardarelli Hospital,Naples, Italy Arnold Ganser, director of the Department of Haematology,Haemostasis, Oncology and Stem Cell Transplantation, HannoverMedical School, Germany Jan Geissler, steering committee member of the Acute LeukemiaAdvocates Network (ALAN); founder and chief executive ofPatvocates; former director of the European Patients’ Academy(EUPATI); and co-founder of LeukaNET, the CML Advocates Networkand the Leukemia Patient Advocates Foundation. Deborah Harkins, AML patient; chief officer health and wellbeing(director of public health), Dudley Council, West Midlands, UK Alessandro Isidori, professor of haematology, Haematology and StemCell Transplant Centre, Marche Nord Hospital, Pesaro, Italy Harpreet Kaur, consultant haematologist, Sheffield TeachingHospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK Pau Montesinos, haematologist, Haematology Department, HospitalUniversitari i Politècnic La Fe, València, Spain The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2019

Acute Myeloid Leukaemiamapping the policy response to an acute cancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK Jenna Ostrowski, AML patient, corporate solicitor, Birmingham, UK Christian Récher, head of the haematology department, ToulouseUniversity Hospital Centre, Toulouse University Cancer InstituteOncopole, France; and Chairman of the French Innovative LeukemiaOrganisation (FILO) study group working party on AML. Nicola Shepherd, clinical nurse specialist in leukaemia and lymphoma,Guy’s Hospital, London, UK Gemma Trout, leukaemia clinical nurse specialist at UniversityCollege London Hospitals NHS Trust, UK Amer Zeidan, associate professor of internal medicine (haematology),Department of Internal Medicine, Yale Cancer Center and SmilowCancer Hospital, Yale University School of Medicine, USThis report was written by Ingrid Torjesen and edited by ElizabethSukkar of The Economist Intelligence Unit. The findings and viewsexpressed in this report are those of The Economist Intelligence Unitand do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsor.December 2019 The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 20193

4Acute Myeloid Leukaemiamapping the policy response to an acute cancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UKExecutive summaryAcute myeloid leukaemia (AML) is the mostcommon form of acute leukaemia in adults,although it is considered a rare disease. Thedisease often affects older people and isuncommon in people under the age of 45.However, incidence is expected to rise with anageing population, which will place demandson healthcare systems.intensity chemotherapy and haematopoieticstem cell transplants. These approachesare physically and mentally demanding forpatients, requiring several bouts of hospitalstays lasting several weeks, and generallyonly feasible in relatively fit and, therefore,younger patients. Other patients are currentlyprovided with supportive care.The direct healthcare costs of AML increasewith the complexity of the care required andmost of the limited research specifically on thedirect costs of AML has focused on treatmentof younger patients who are fit enough toreceive intense treatment.This report looks at the incidence, diagnosis,treatment and costs of AML and theexperience of patients in these five Europeancountries, with the aim of highlighting areasof particular attention to policymakers. Basedon qualitative interviews and desk-basedresearch, it is clear that there are a number ofchallenges that policymakers and healthcareprofessionals will need to address to improveoutcomes for those living with AML.This report looks at five countries inEurope—France, Germany, Italy, Spain andthe UK—finding that the UK has the highestprevalence of the condition, at more than5,000 cases, while Spain has the lowest, atunder 2,300 cases. The condition also has thefifth worst five-year survival by cancer type,after pancreatic, lung, liver and oesophagealcancers, and is responsible for 62% of allleukaemia deaths.AML occurs when there is a build-up ofcytogenetic changes in blood stem cells(haematopoietic stem cells) that interfereswith the production of normal blood cells.Patients initially experience non-distinctsymptoms such as fatigue and repeatedinfections, but as the number of abnormalblood cells (known as blast cells) rises, patientsare likely to exhibit bruising and bleeding.Ultimately, their blood will contain so fewnormal cells that the condition becomes lifethreatening.The goal of active treatment is remission,and current approaches are focused on high The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2019Key findings:Awareness raising of symptoms amongprimary care physicians and the publiccould speed up diagnosisAlthough the initial symptoms of AML areindistinct, a simple blood test will show animbalance of blood cells that warrants urgentinvestigation. However, as is the case withmost rare diseases, patients report difficultiesin obtaining a diagnosis. This is especially thecase in the UK, where general practitioners(GPs) act as gatekeepers to hospital services(where patients with AML will ultimatelyreceive treatment). Unexplained bleedingor bruising, alongside indistinct symptomssuch as fatigue and infections, should prompta blood test to exclude haematologicalmalignancy. Raising awareness of this amongprimary care physicians and the public couldhelp to speed up diagnosis for some patients.

Acute Myeloid Leukaemiamapping the policy response to an acute cancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UKGuidelines with a greater focus on holisticmanagement and maximising patients’quality of life neededManagement of AML in Europe is basedprimarily on the 2017 European LeukaemiaNet(ELN) guidelines.1 This document is focusedon clinical management of the diseasein the acute stage. The extent to whichpatients receive holistic and psychosocialsupport from a multidisciplinary team andsupport services varies between and withinEuropean countries. Wider-ranging guidanceis needed, taking into account treatment sideeffects, impact on quality of life and need forpsychosocial support.Greater centralisation of services iswarrantedThe care of rare and complex diseases isusually best placed within a few centres ofexcellence, so that patients are treated byprofessionals who have broad experience ofmanaging the condition, as well as access toa wide range of dedicated support services.Experts recommend that this would be thebest approach for AML.Faster genetic testing is required fordiagnosis and monitoringEach patient with AML has a unique profile ofcytogenetic abnormalities, and these affecttheir prognosis and which treatments aremost likely to be effective. Therefore, patientswith AML should receive genetic testing. Thespeed at which the results of cytogenetic testsare available post diagnosis to haematologistsvaries across Europe, from a few days to a fewweeks. The results of these tests will becomeever more important as a greater number oftargeted therapies, which are only effectivefor patients with particular mutations andneed to be started soon after diagnosis,become available. As the cytogenetics of AMLevolve and change, these tests also need tobe repeated intermittently to ensure that themanagement approach taken offers patientsthe best potential outcome. Such testingallows more accurate detection of minimalresidual disease to stratify patients accordingto their risk of relapse and prognosis.2Investing in these tests has the potential toimprove outcomes for patients.Improving the care experience for patientsIt is not uncommon for patients to spendat least four weeks at a time in hospital toreceive intensive chemotherapy, where theywill be kept isolated to protect them frominfection. Extended visiting hours, and accessto free WiFi and television can greatly improvepatients’ hospital experience by enablingthem to maintain relationships, keep up todate with work or study, and generally remainoccupied. Initiatives to provide more “homely”accommodation alternatives to regularhospital wards—or allowing patients to betreated as outpatients where possible—canalso have benefits for wellbeing and reducecosts. In the future, greater availability oftargeted medications is likely to increasethe potential for patients to be treated asoutpatients; it would be prudent to designclinical pathways to support this, as well asensuring the availability to health providers ofappropriate services needed to manage morepatients closer to home through shared carearrangements.1 Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D et al, “Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel”,Blood, 2017 Vol. 129, No. 4, 2017, pages 424-447. oi/10.1182/blood-2016-08-7331962 Hante A, Stock W, Kosuri S, “Molecular Minimal Residual Disease Testing in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Review for the Practicing Clinician”, Clinicallymphoma, myeloma & leukemia, Vol. 18 No. 10, 2018, pages 636-647. -2650(18)30480-4 The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 20195

6Acute Myeloid Leukaemiamapping the policy response to an acute cancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UKA louder patient voiceMost patient support organisations thatfocus on haematological cancers are smalland resource poor, and focused on givingsupport to patients during active treatment.Patients would benefit if these groupswere able to extend the support that theyoffer to after-care for “survivors” who needadvocacy support to help them speak abouttheir experiences to raise awareness of thecondition among the public and amongpolicy makers. Expert patients can provideuseful support, information and hopefor patients recently diagnosed with thedisease. Policymakers should involve patientrepresentatives more in decisions in policyand service development around rare acuteleukaemia. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2019Improving data collection will informservice provisionComprehensive data on the epidemiology,genetics, management and outcomes (survivaland minimal residual disease) of AML is notcurrently collected. Initiatives to improve datacollection and share it across Europe shouldbe supported. Where registries exist, they arefocused on patients who are actively managedthrough clinical trials. A more accurate pictureof incidence and prevalence is needed sothat countries can ensure that their specialistservices can cope with the growing numberof patients with AML, the right numbers ofspecialist healthcare staff are trained andrecruited, and services and treatmentsare appropriately funded. Europe-widecollection of anonymised patient data willalso support efforts to better understand thedisease mechanism of AML, as well as whichcytogenetic profiles are linked with the bestresponses to particular treatments and theirlong-term outcomes.

Acute Myeloid Leukaemiamapping the policy response to an acute cancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UKChapter 1: Introduction—what is AML?An acute leukaemiaAcute myeloid leukaemia (AML) is the mostcommon form of acute leukaemia in adults,and its incidence increases with age.3,4 Survivalcan vary substantially, ranging from 35-40% inadults aged 60 and below to as low as 5-15%in older patients, who are often not fit enoughfor intensive therapy and may be managedonly with supportive care.5The cause of AML is generally unknown, butpeople may develop it following exposure tocertain agents, such as radiation, particularchemicals or prior treatment for cancer, orfollowing another haematological disorder.6Blood cells are made in the bone marrowwhen haematopoietic stem cells divide toproduce progenitor cells, which developinto immature blast cells and, finally, fullyfledged blood cells. There are two types ofprogenitor cells, myeloid and lymphoid. AMLaffects progenitor myeloid cells, which are theprogenitor cells for red blood cells, plateletsand all white blood cells, except lymphocytes.7AML comes about as a result of successivegenomic alterations in stem cells. Largechromosomal translocations, as well asmutations in key genes involved in the division,growth and development of the cells, resultin the accumulation of poorly differentiatedmyeloid cells.8Chronic forms of leukaemia develop moreslowly, whereas acute forms can becomelife threatening very quickly, meaning thatpatients affected by the latter often needprompt diagnosis and urgent specialist andmultidisciplinary treatment, which placesincreased demands on healthcare systemsand providers.A genetically complex malignancyAML is a very complex and diversemalignancy, which makes managementand treatment a challenge. Molecular andcytogenetic abnormalities in AML can involvemutations in critical genes of normal celldevelopment, cellular survival, proliferationand maturation. Targeting these pathwayswithout inducing toxicity in healthy cells istherefore a challenge.In almost every patient with AML, multiplemalignant cell clones exist. Each of thesesubclones is characterised by a uniqueconfiguration of genetic and epigeneticabnormalities that may influence prognosisand response to treatment.9Healthcare providers therefore need tounderstand that AML requires an individualisedapproach to treatment. The identification ofgenetic mutations, such as FLT3-ITD, NMP1and CEBPA, has helped to refine individualprognosis and guide management.103 Löwenberg B, Rowe JM, “Introduction to the review series on advances in acute myeloid leukemia (AML)”, Blood, Vol. 127, No.1, 2016, epub. is RM, Wang R, Davidoff A, Ma X, Zeidan AM. Epidemiology of acute myeloid leukemia: Recent progress and enduring challenges. Blood Rev.2019 Jul;36:70-87. Doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2019.04.005. Epub 2019 Apr 29.5Editorial, “Closing in on targeted therapy for acute myeloid leukaemia”, Lancet Haematology, Vol. 6, 2019, page e1. nberg B, Rowe JM, “Introduction to the review series on advances in acute myeloid leukemia (AML)”, Blood, Vol. 127, No.1, 2016, epub. wise, “Acute Myeloid Leukaemia”. d-leukaemia8Löwenberg B, Rowe JM, “Introduction to the review series on advances in acute myeloid leukemia (AML)”, Blood, Vol. 127, No.1, 2016, epub. 10De Kouchkovsky I, Abdul-Hay M, “Acute myeloid leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2016 update”, Blood Cancer Journal, Vol. 6, 2016, page e441.http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2016.50 The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 20197

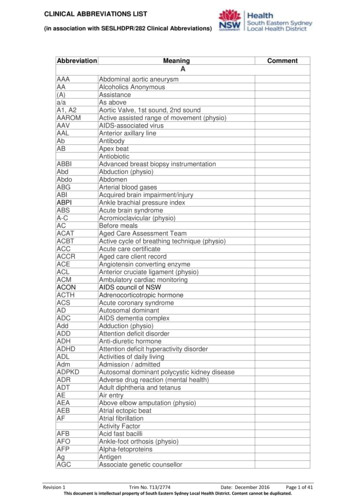

8Acute Myeloid Leukaemiamapping the policy response to an acute cancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UKHowever, in addition to genetic alterations inthe DNA, AML is also affected by epigeneticalterations, which may profoundly disrupta variety of key intracellular pathways.Epigenetic alterations are changes in geneexpression that are inheritable by cell divisionbut not caused by changes in the DNA itself.11In 2016 the World Health Organisation(WHO) updated its classification of myeloidcancers and acute leukaemias, recognisingthe significant cytogenetic and molecularsubgroups of AML. Although most cases ofacute leukaemia or myelodysplastic syndromeare not inherited genetic defects, the WHOrecognises that some cases are associatedwith germline mutations that are inherited.12,13Other types of AML include: therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, wherepatients develop cancer following cytotoxictreatment; AML with myelodysplasia-related changes,which has a particularly poor prognosis andis more common in the elderly;14 acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL);this form of AML is considered a medicalemergency and managed differently, butis curable if treated promptly.15 Almost allpatients have a specific faulty gene calledPML/RARA, where there is a translocationof chromosomes 15 and 17 - t(15;17).16Patients with suspected APL undergo adifferent clinical management to AML; AML types that do not fit into other groups.17Understanding and quantifying theburden in EuropeAML is generally a disease of older peopleand is uncommon before the age of 45. Theaverage age of people when they are firstdiagnosed with AML is about 68.18,19This report looks at five major economies inEurope, finding that the UK has the highestprevalence of AML, at more than 5,000 cases,while Spain has the lowest at under 2,300cases, according to data from the GlobalBurden of Disease Study 2017 (see Figure 1 ).AML is slightly more common among menthan women, and the average lifetime risk ofAML in both sexes is about 0.5%.20The incidence of AML is believed to be broadlysimilar across European countries, at around3.5 cases per 100,000 population per year(there were an estimated 17,746 new cases inthe EU in 2013).21, 2211 Wouters BJ, Delwel R. Epigenetics and approaches to targeted epigenetic therapy in acute myeloid leukemiaBlood Vol 127, 2016, pages42-52; doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-07-60451212West AH, Godley LA, Churpek JE, “Familial myelodysplastic syndrome/acute leukemia syndromes: a review and utility for translationalinvestigations”, Ann N Y Acad Sci, Vol. 1310, 2014, pages 111-118. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.1234613Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al, “The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia”,Blood, Vol. 127, No. 20, 2016, pages 2391-2405. oi/10.1182/blood-2016-03-64354414American Cancer Society, “Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Subtypes and Prognostic Factors”. 5Sanz MA, Fenaux P, Tallman MS et al, “Management of acute promyelocytic leukemia: Updated recommendations from an expert panel of theEuropean LeukemiaNet”, Blood, Vol. 133, No. 15, 2019, pages 1630-1643. odwise, “Acute promyoelcytic leukaemia”. locytic-leukaemia17Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al, “The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia”,Blood, Vol. 127, No. 20, 2016, pages 2391-2405. oi/10.1182/blood-2016-03-64354418American Cancer Society, “Key Statistics for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)”. ia/about/keystatistics.html19Shallis RM, Wang R, Davidoff A, Ma X, Zeidan AM, “Epidemiology of acute myeloid leukemia: Recent progress and enduring challenges”, Blood Rev,Vol. 36, 2019, pages 70-87. -960X(18)30139-520 American Cancer Society, “Key Statistics for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)”. ia/about/keystatistics.html21Miranda-Filho A, Piñeros M, Ferlay J et al, “Epidemiological patterns of leukaemia in 184 countries: a population-based study”, Lancet Haematol Vol.5, 2018. Pages e14–24. ta G, Capocaccia R, Botta L et al, “Burden and centralized treatment in Europe of rare tumours: results of RARECAREnet—a population-basedstudy”, Lancet Oncol, Vol. 18, No. 8, 2017, pages 1022-1039. -2045(17)30445-X The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2019

Acute Myeloid Leukaemiamapping the policy response to an acute cancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UKFigure 1: Prevalence of acute myeloid leukaemia in the EU5, all ages (number of cases), 2017All-age deaths 2,836Spain2,216Source: Institute for Health /Global Burden of Disease Study 2017; data compiled by EIU analyst Darshni Nagaria.Figure 2: Incidence of acute myeloid leukaemia in France by age, 2017MaleIncidence rate (per 100,000)40FemaleBoth353025201510595 40-4435-3930-3425-2920-2415-1910-145-91-4 10Age rangeSource: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation/Global Burden of Disease Study 2017; data compiled by EIU analyst Darshni Nagaria. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 20199

Acute Myeloid Leukaemiamapping the policy response to an acute cancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UKFigure 3: Incidence of acute myeloid leukaemia in Germany by age, 2017MaleIncidence rate (per 100,000)40FemaleBoth353025201510595 40-4435-3930-3425-2920-2415-1910-145-91-4 10Age rangeSource: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation/Global Burden of Disease Study 2017; data compiled by EIU analyst Darshni Nagaria.Figure 4: Incidence of acute myeloid leukaemia in Italy by age, 2017Male35Incidence rate (per 100,000)FemaleBoth30252015105Age rangeSource: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation/Global Burden of Disease Study 2017; data compiled by EIU analyst Darshni Nagaria. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 201995 40-4435-3930-3425-2920-2415-1910-145-91-40 110

Acute Myeloid Leukaemiamapping the policy response to an acute cancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UKFigure 5: Incidence of acute myeloid leukaemia in Spain by age, 2017MaleIncidence rate (per 100,000)30FemaleBoth25201510595 40-4435-3930-3425-2920-2415-1910-145-91-4 10Age rangeSource: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation/Global Burden of Disease Study 2017; data compiled by EIU analyst Darshni Nagaria.Figure 6: Incidence of acute myeloid leukaemia in UK by age, 2017MaleIncidence rate (per 100,000)80FemaleBoth7060504030201095 40-4435-3930-3425-2920-2415-1910-145-91-4 10Age rangeSource: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation/Global Burden of Disease Study 2017; data compiled by EIU analyst Darshni Nagaria.The incidence of AML overall is increasing.23, 24When looking at AML by incidence, the peaktends to be in older people and in men (seeFigures 2-6; based on data from the GlobalBurden of Disease Study, 2017). In Germany,for instance, the incidence of AML in bothsexes is less than six cases per 100,000population in those 69 years of age or younger,but rises to 28 per 100,000 in 80-to-84-yearolds.According to Dr Harpreet Kaur, consultanthaematologist at Sheffield Teaching HospitalsNHS Foundation Trust in the UK, “incidenceworldwide has risen by nearly a third overthe [past] couple of decades, because peopleShallis RM, Wang R, Davidoff A, Ma X, Zeidan AM, “Epidemiology of acute myeloid leukemia: Recent progress and enduring challenges”, Blood Rev,Vol. 36, 2019, pages 70-87. -960X(18)30139-524Cancer Research UK, “Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) incidence statistics”, aemia-aml/incidence The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 20192311

12Acute Myeloid Leukaemiamapping the policy response to an acute cancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UKare living longer and the age of onset is fairlyelderly and patients treated with biologicalagents for other cancers are surviving butdamage has been done to other bystanderorgans, including the bone marrow”.25Survival rates for rare cancers are lowerthan for more common cancers, and forAML they are particularly low. AML has thefifth worst five-year survival by cancer type(after pancreatic, lung, liver and oesophagealcancers), and is responsible for 62% of allleukaemia deaths.26Five-year survival for AML isestimated to be around 24%Based on data from 94 cancer registries inEurope from 2000 to 2007, five-year survival forAML in the EU was estimated at 17.5%.27 Morerecent US data from 2016 estimate five-yearsurvival to be 24%, with median survival of 8.5months.28 While mortality from chronic formsof leukaemia such as chronic myeloid leukaemiaand chronic lymphocytic leukaemia has beenfalling, the mortality rate for AML remainedrelatively stable between 2005 and 2016.29Survival rates for AML vary markedly betweenage groups owing to the treatment theyreceive. Approximately 35-40% of patientsunder 60 years of age may obtain long-termsurvival with current forms of aggressivetreatment, while elderly patients can rarelytolerate aggressive regimens, and so theirprognosis is much worse.30 Overall, medianoverall survival for a patient diagnosed aged65 years or more is 2.7 months, and nearly80% of patients in this group will die withinone year, with the most elderly having theshortest survival time.31Across patients receiving aggressive treatmentthere is also a wide variation in survival, dueto the range of genetically distinguishablesubsets of the disease, with some subtypeshaving particularly poor outcomes.European LeukaemiaNet classifies patientsinto three prognostic risk groups according totheir genetics: favourable, intermediate andadverse.32 Validation of this classification inthe under 60s found five-year survival ratesto be 57% in the favourable group, 37% in theintermediate group and 18% in the adversegroup.33 In the over 60s, another study foundthree-year overall survival for patients with afavourable prognosis to be 30%; this drops to12% for those in the intermediate group and6% in the adverse risk group.3425 Ibid.26Shallis RM, Wang R, Davidoff A, Ma X, Zeidan AM, “Epidemiology of acute myeloid leukemia: Recent progress and enduring challenges”, Blood Rev,Vol. 36, 2019, pages 70-87. -960X(18)30139-527Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Botta L et al, “Burden and centralized treatment in Europe of rare tumours: results of RARECAREnet—a population-basedstudy”, Lancet Oncol, Vol. 18, No. 8, 2017, pages 1022-1039. -2045(17)30445-X28Shallis RM, Wang R, Davidoff A, Ma X, Zeidan AM, “Epidemiology of acute myeloid leukemia: Recent progress and enduring challenges”, Blood Rev,Vol. 36, 2019, pages 70-87. -960X(18)30139-529Ibid.30Editorial, “Closing in on targeted therapy for acute myeloid leukaemia”, Lancet Haematology, Vol. 6, 2019, page e1. lis RM, Wang R, Davidoff A, Ma X, Zeidan AM, “Epidemiology of acute myeloid leukemia: Recent progress and enduring challenges”, Blood Rev,Vol. 36, 2019, pages 70-87. -960X(18)30139-532Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D et al, “Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expertpanel”, Blood, 2017 Vol. 129, No. 4, 2017, pages 424-447. oi/10.1182/blood-2016-08-73319633Prajwal C, Boddu MD, Tapan M, Kadia MD, Garcia-Manero G et al, “Validation of the 2017 European LeukemiaNet classification for acute myeloidleukemia with NPM1 and FLT3‐internal tandem duplication genotypes”, Cancer Vol. 125, No. 7, 2019, pages 1091-1100. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.3188534Eisfeld AK, Kohlschmidt J, Mrozek K, et al, “Mutation patterns identify adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia aged 60 years orolder who respond favorably to standard chemotherapy: an analysis of alliance

The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 019 Acute Myeloid Leukaemia: mapping the policy response to an acute cancer in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK is an Economist Intelligence Unit report, supported by Amgen, a pharmaceutical comp