Transcription

The Foster Parent Resource GuideTST-FC: A TRAUMA-INFORMED CAREGIVING APPROACHAPRIL 2017THE ANNIE E. CASEY FOUNDATIONTHE ANNIE E. CASEY FOUNDATION-1-

TST-FC: TRAUMA-INFORMED CAREGIVINGTrauma Systems Therapy for Foster Care (TST-FC) was adapted from Trauma SystemsTherapy, developed by Dr. Glenn Saxe of NYU’s Child Study Center. The Foster ParentResource Guide was written by Kelly McCauley, LSCSW, with consultation from Dr.Saxe. Development of the guide was supported by the Annie E. Casey Foundation andincludes work adapted from materials developed by Dr. Marion Forgatch and Dr. GlennSaxe and adapted by Dr. Connie Keeling and Dr. Linda Bass. The Self-Care Assessment isfrom Saakvitne, K. W., & Pearlman, L. A. (1996). Transforming the pain: A workbook onvicarious traumatization, and was adapted by Kelly Young, LSCSW.TECHNICAL ASSISTANCEFor more information about TST-FC, please contact the Child Welfare Strategy Group atwebmail@aecf.org. 2017, The Annie E. Casey Foundation, Baltimore, Maryland

contentsi. INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1I. CHAPTER 1: Understanding Trauma and My Child . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Trauma’s effect on children’s emotions and behavior . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Understanding the 4 R’s . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6Understanding survival-in-the-moment states . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8Learning about the cat and the cat hair . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10Understanding signals of stress . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Three trauma stories: John, Sophia and Hector . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13TST-FC, your team and you . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15More resources on trauma . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17II. CHAPTER 2: Preparing for Success With My Child. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19Two tools: The MEG and practicing emotional regulation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19Developing and using centering plans . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27My centering plan (a worksheet) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31Talking about psychological safety . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33How to use pre-teaching . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35A pre-teaching worksheet to help you plan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37Helping a child build self-control (an exercise) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39“The Child I Care About” worksheet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Moment-by-moment assessment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47The priority challenge worksheet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49About revving: Learning, role playing and reviewing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53How did it go? (a revving review worksheet) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55III. CHAPTER 3: Handling Challenging Behavior in the Moment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57Staying calm and neutral . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58Increasing signals of safety . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59Using centering plans . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61Avoiding power struggles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62Avoiding power struggles (a worksheet). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63Helping a child who is having a meltdown moment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65Introducing “time-in” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66Knowing what to do before, during and after an emergency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67Family emergency information form . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69IV. CHAPTER 4: Finding Energy and Hope . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71Your self-care assessment (a worksheet) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

iintroductionYou are caring for one or more children who need your support. They haven’t always had an easy life andwhat they learn while in your home, in your care, can make a real difference.During your TST-FC training you will learn a lot about how you can help particular children, teenagers orsiblings in your home. This booklet will help you remember and practice what you learned.Some of the exercises are for you — to help you figure out what overwhelms a child and what centers himor her. Some may help you recognize your own trauma triggers and how they may affect your parenting.Other exercises can be done with the child and with others in your family. The idea is for everyone to getmore comfortable experiencing strong feelings without becoming overwhelmed.GET IDEAS FASTPay special attention to Chapters 3 and 4. Look there when you’re at your wit’s end and need ideas fast.There is a review of strategies for working in the moment with children who are struggling. There are alsomaterials to remind you to take care of yourself, since you are an important part of your child’s team.Thank you for your commitment to the children in your care.Tracey FeildManaging DirectorChild Welfare Strategy GroupThe Annie E. Casey FoundationKelly McCauleyAssociate DirectorKVC Institute for Health Systems InnovationKVC Health Systems, Inc.-1-

-2-

Ichapter oneUnderstanding Trauma and My ChildDuring your TST-FC training, you learned how trauma affects a child’s emotions and behavior. Now,instead of asking, “What’s wrong with this child?” you ask, “What has happened to this child?” Youunderstand that children’s experience with trauma may shape how they act.This chapter will remind you of what you have learned and help you extend your knowledge.It will help you: Learn about trauma’s effect on children’s emotions and behavior Understand the 4 R’s Understand survival-in-the-moment states and how the brain responds to threat Learn about TST, your team and you Learn about the cat, the cat hair and the 4 R’s Understand signals of stress Read and think about three trauma stories (John, Sophia and Hector) Find more resources on trauma-3-

TRAUMA’S EFFECT ON CHILDREN’S EMOTIONS AND BEHAVIORWhy is there a specific training on trauma for kin and foster caregivers? It’s because, almost without exception,trauma is the norm for children in foster care. Nearly every child in the foster care system has experiencedat least one traumatic event. One in four have experienced four or more different types of trauma.Parenting children with trauma in their past calls for a different approach. As a caregiver, you may not be ableto count on solutions that your parents used with you or that you used with other children.Children in foster care have often experienced trauma in the context of important relationships with adultsin their lives. They may have suffered physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual assault and neglect. Asa result, they may struggle to handle strong feelings, such as rage, terror and anxiety. They may beverbally or physically aggressive or numb and emotionally shut down. They may make inappropriatechoices or harm themselves by abusing substances, cutting and running away. They may be fearful ofletting adults know they are lesbian, gay or questioning their sexual identities. They may have a hard timeconcentrating, learning and trusting or respecting authority.For children in foster care, everything stands or falls on the quality of their relationships. Their healing mustoccur within the context of their relationships with family, peer groups, school, community and culture.Who is here for me?To move beyond trauma, a child needs to know the answer to the question, “Who is here for me?” This isjust one reason why living in a family, and finding a lifelong family, is so critical. A child must know wherehe or she belongs.Kin and foster caregivers are important in this process. You can show children who have experiencedtrauma that you will stick with them through thick and thin. You can help them form meaningful, positiveconnections — to themselves, to family, to their communities. You can help children process what hashappened to them and build needed emotional and behavioral self-controls that were stunted by trauma.Healing and building new relationship skills takes time and practice. You need to be right there withchildren as they go through good and bad days. This can be challenging, especially when children pushyou away even as they need you to hold them close. They may use coping mechanisms — such as lashingout in anger, retreating into themselves — to protect themselves, even though those mechanisms oftenhave the opposite effect. Your willingness to stand by a child can be a lifesaver.OverwhelmedWhat is trauma? It is a life threatening or extremely frightening incident or environment experienced by achild or someone they care about that overwhelms the child’s ability to cope. There are three categories: Acute trauma. This includes frightening, one-time, time-limited events with a start and a stop, such asdog bites, car accidents or natural disasters. Chronic trauma. Children may experience ongoing, repeated patterns of terrible events, such asphysical, sexual or emotional abuse, domestic violence and neglect. Complex trauma. Children may face extreme experiences beginning when they are younger than 5years old that are brought about by people who are supposed to care for them.-4-

Trauma can disrupt healthy brain development, especially for children who experience complex trauma.It can also disrupt healthy caregiver attachment. This means children can lack relationships that, for mosthumans, are the foundation of normal development.Ineffective coping strategiesTrauma often forces children to develop coping mechanisms that make sense in the midst of lifethreatening trauma but not in everyday life. These may include faulty: Internal coping strategies. All of us develop ways of handling difficult circumstances and emotions, suchas stress, hardship, disappointment and fear, in our own minds and bodies. We may take a break from asituation when it gets too hard to handle. We may have self-soothing rituals. We may ignore a problemuntil we have more energy to deal with it or try to think of positive aspects of a difficult situation. External coping strategies. Sometimes we seek support or help dealing with difficulty by reachingbeyond ourselves. We may reach out to a friend or family member, get involved in a different activitysuch as gardening or shopping, leave the situation or drink alcohol.These strategies may be more or less effective, depending on the stressful situation and how successful weare at finding relief via our internal and external coping strategies.For children who have experienced trauma, their internal and external coping mechanisms may not be agood match for their day-to-day lives. Children may be reminded of a past trauma without being aware ofit, then use inappropriate coping mechanisms because they are re-experiencing the terror they felt in theoriginal instance of trauma. Sometimes that reminder is something as simple — and as nonthreatening —as a similar scent, a time of day or a person’s accent.TST-FC will help you understandThis training helps you understand why children have responses that seem like a mismatch with theircurrent situation. It reminds you to ask, “What happened to this child?” instead of “What’s wrong withthis child?” It helps you understand that before you think of disciplinary measures, before you decidewhether a child is being obedient or respectful, you need to understand what frightening feelings thesituation has sparked in the child.In your TST-FC sessions, you will learn about something called “the cat and the cat hair.” You will find areminder about what that means in this binder. Using the TST-FC approach, you and the child’s team willbrainstorm about what your child’s cat hair might be, think of ways to decrease the cat hair in his or herenvironment and build the child’s problem-solving and coping skills to face those triggers when they occur.You will learn that, because of trauma, children may have a broken off switch. Their brains may not realizethat the terrible danger they once faced is over. You will learn about survival-in-the-moment states. This iswhen a child has that zero-to-60 response and hurtles from being calm and relaxed to fearful and terrifiedin seconds. You will learn about the 4 R’s — the four stages of emotions and behavior that help youunderstand which parenting approach will help the child stop feeling so overwhelmed.Your parenting roleTST-FC seeks to help you, as a kin or foster caregiver, to create a safe, calming environment. You willbe able to help your child develop effective coping mechanisms. You will also help him or her buildemotional and behavioral skills to keep from feeling overwhelmed by reminders of past traumas.-5-

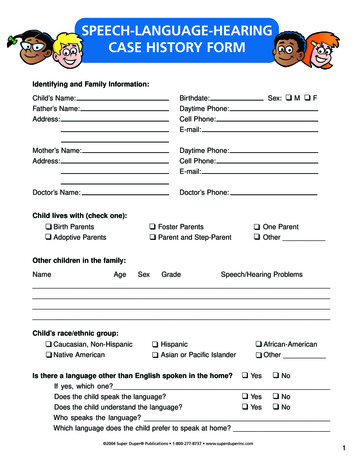

UNDERSTANDING THE 4 R’STST-FC describes four stages of behavior common to children who have experienced trauma. We callthem the 4 R’s. Key things to remember about the 4 R’s: Not only does children’s behavior vary from one stage to another, but so should your behavior. Whenchildren are regulated and calm, your priority is to minimize triggers. When children are revving, yourpriority is working with them to use whatever skills they use to regulate their emotions. It’s not just children’s observable behavior that varies from one stage to another. So do children’s heartrates, thinking styles, sense of time and more.STAGES OF BEHAVIOR (THE 4 NGChild behaviorRestful. Child is calmand engaged in his orher environmentVigilant. Child has beentriggered and is tryingto manage emotionsFight, flight or freeze. Child’s copingskills are overwhelmed; s/he isstrugglingCalming down. Child isbeginning to manageemotions and re-engageYour priorityMinimize triggers toprevent escalationHelp your child regulateemotionMake sure your efforts to containthe child do not re-traumatize himor herHelp your childcontinue to manageemotions and re-engageHeart Rate70-9090-100Freeze101-110Thinking styleAbstractConcreteEmotionalActive brainregionCortexLimbicMidbrainInternal stateCalmAlertAlarmSense of timeExtended futureDays, hoursHours/MinutesFlight111-135Fight136-160Slowly returns tobaselineReactiveReflexiveSlowly returns rSlowly returns to calmMinutes/SecondsNo senseof timeCan see into the futureagainThe 4 R’s include: Regulating. Most of the time, children are in a regulated state. Their heart rate is normal. The morecomplex parts of their brain are working well. They are calm and can think about the future. They cansit quietly in the classroom, eat a pleasant family meal or complete their chores. They can manage theiremotions and their behavior. Revving. When a trigger appears — the sound of someone’s voice, an anniversary date or beingredirected — children quickly enter the revving stage. They become hyper-alert. They shift their focusfrom what they were doing to the perceived source of threat. Their body starts to prepare for fight, flightor freeze. They experience rapid breathing, increased heart rates and muscle tension. Emotions expandand they become intensely angry or fearful. Or they become emotionally numb and shut down.-6-

Re-experiencing. If children cannot calm down and no one can help them feel safe, they may quicklygo to re-experiencing behaviors of fight, flight or freeze. This is when they face the greatest risk ofharming themselves or others. Reconstituting. Eventually, children will calm down. It is important to know that children in this stageare very sensitive to stress in their environment and can quickly return to the re-experiencing stage.What do changes in behavior stages look like?A child who is in the relaxed stage may play calmly, focusing her attention on a toy with a look of curiosityon her face. But when a loud woman comes into the room who reminds the child of an abusive formerneighbor, that same child may no longer be able to listen. She may act terrified. She may kick and scream.Or she may withdraw and refuse to speak. She might not even be aware that these changes took place in asplit second. She may be re-experiencing her past trauma, even though the loud woman who entered theroom is not trying to hurt her.Other ways to gauge behavior stagesChildren’s affect, awareness and action may give clues about their stage of behavior. What these terms mean: Affect. How people display their feelings, especially on their faces or in their body language, is calledtheir affect. Sometimes a person’s affect does a good job showing how they feel. For example, a happyperson’s face may light up with a smile. On the other hand, sometimes people hide their feelings. Peoplewho are scared or upset might have a blank look on their faces to hide their pain. This is called having a“flat affect.” Awareness. Are you aware how your mood and current and past experiences affect how you are feelingand acting right now? Maybe you feel exhausted. No one likes to feel that way, but it might help if yourealize that you simply have a cold and will soon feel better. If you didn’t have that awareness, it mightbe easier for you to become overwhelmed. You might think, “I never have any energy! I will never beable to finish my work.” Children who have experienced trauma often have limited awareness of howtheir mood and past experiences affect them in the present moment. Action. Sometimes we act happy or frightened. Sometimes we act energetic. Our actions are a way toexpress how we feel. If we are terrified, we may act that way — by being aggressive or pushing peopleaway, as children who have experienced trauma frequently do.-7-

UNDERSTANDING SURVIVAL-IN-THE-MOMENT STATES AND HOW THE BRAIN RESPONDS TO THREATThe human body and mind work closely together to respond when we feel threatened. Our five sensesprocess information from the outside world, our emotions drive action and our bodies respond quickly.These mental, emotional and physical responses focus us on one thing: survival.What are survival-in-the-moment states?Survival-in-the-moment states come about quickly. A child is faced with a terrifying situation or isreminded, even indirectly, of a past trauma. This drives him or her into a fight, flight or freeze response.When these mental, emotional and physical responses kick in, they are often immediate, extreme andoutside a child’s conscious control. It is hard for children to behave calmly and think clearly. They canfeel anxious, worried, nervous or fearful, even when there is no active source of threat. Parents and familymembers describe kids as looking on guard, defensive or out of control.Survival-in-the-Moment StatesSurvival-in-the-moment states affect a child’s mental, emotionaland physical well-being, including the following: Awareness of self and the environment Experience of intense feelings Physical responses Ability to cope9Why does this happen?Survival-in-the-moment states are part of our emergency response systems. When a threat is sensed, ourbrains do not have time to figure out if it is real. The brain has two choices: The low road and the high road.Our low road manages threat. It is a simple reflex — it just reacts.The high road is a little slower. It provides context. The high road senses danger but also tries to determinewhether a threat actually exists. It sizes up the danger. If danger really is likely, the brain heightens the alerteven more. If danger is not likely, the brain stands down and tells the brain to relax.Overusing the low roadIn children who have experienced repeated abuse or neglect, the low road is overused. When they sense athreat to their safety, or the safety of someone they care about, their brains react swiftly, without thinking.This happens whether the threat is real or not. Their brains do not stop to consider reality or the details ofwhat is happening.-8-

For children who have been in dangerous or terrifying situations over and over again, the low roadbecomes hardwired. It becomes the way they react. The result is that they begin to perceive threat insituations where it may not exist.RememberTwo important lessons about survival-in-the-moment states: Don’t take the child’s response personally. Survival-in-the-moment states happen so quickly that theyare often beyond a child’s immediate control. Your job is to keep the child and others safe and providethe time, support and space for the child to return to reality. Your assistance can make a difference. Children who have experienced trauma need to practice,practice, practice feeling safe and experiencing self-control. Your persistence, support and help withskill building can hardwire new responses in a child’s brain.When you and the child need help: Remember, children who shut down, isolate or become numb have the highest rates of suicide andself-harm. Should you ever have any concern about a child with these characteristics, contact a mental healthprofessional and the child’s social worker immediately. Together you can plan an intervention anddevelop a safety plan.-9-

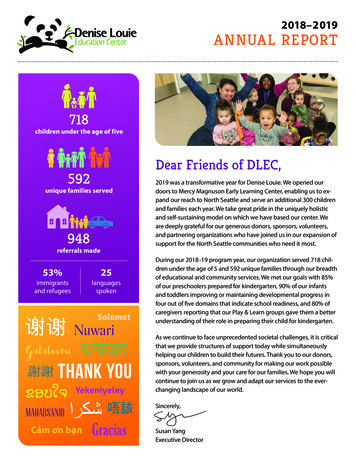

LEARN ABOUT THE CAT AND THE CAT HAIRJaak Panksepp was a scientist who studied the idea of joy. He wanted to try to find a way to measure joy sohe counted the number of times lab rats played (which is apparently a lot). He was impressed!Panksepp wanted to know what would happen to the level of play if he introduced a source of stress intothe rat’s environment. So he placed a single hair from a cat into the rat’s cage. Remember, these were labrats and they had never even seen a cat before.Amount of Play Over 10 DaysCat hair introducedCat hair removedIn Panksepp, J. P. (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundation of human and animal emotions. New York: Oxford University Press.33What happened? The rats’ level of play fell off dramatically. It never returned to normal.What can we learn from this? Every living being has the need for safety and security. When our safety isthreatened, we feel a big response. This trait is in our biology. The drive to survive is hardwired in each of us.When we must focus on survival, other areas of our life suffer. Things like play, learning and buildingrelationships suffer when children have to focus just on staying safe.Good news: Children can recoverUnlike the lab rats, who never received treatment, children can and do get better with help. In fact, ourbrain chemistry and structure can be rewired up until the age of 25 or 30. The impact of trauma on brainfunctioning does not have to be permanent. But we do need to act now. The longer these unhealthypatterns remain, the harder it is for the child to heal.What you need to knowIt is important to identify each child’s cat and cat hairs.The cat is a real or possible risk of harm. The cat hair is a reminder of past danger. For one child, the catmay be a bully in the neighborhood. The cat hair may be walking by a particular tree where he was oncebeaten up on his way to school. Or the cat may be mom’s abusive boyfriend, with the cat hair being thesound of a man’s raised voice.- 10 -

Often loss of control is a cat hair for children. Being redirected, told “no” or being in strange situations canremind children of times when their power was taken away and scary things happened.When a child becomes withdrawn or aggressive or can’t be consoled, it may be that his or her behavior isn’tabout defiance or being disrespectful or purposely causing trouble. It may be about survival in the moment.How can you tell when children are having survival-in-the-moment responses? Look for changes in theirfacial expressions, gestures or tone of voice. Look for changes in their actions and awareness.Possible Cat Hair or Trauma RemindersSensoryTime DrivenSmells Sights Holidays Sounds Seasons Physical contact Times of the day Tastes Anniversary datesConditions Loss of controlSuch as thingsbeing taken away,being told “no” orre-directedTransitions Changing from oneactivity to another Going from thefamiliar to theunknown36Behavior is a powerful communicator. The less you react to children’s behavior, the more you can taketime to figure out what their behavior is telling you. Seeing past the behavior to the child within helps youconnect with children.Trauma is not the cause of all misbehavior. But if you ignore a child’s trauma history, you may miss apowerful driver of a child’s emotional and behavioral challenges.- 11 -

UNDERSTANDING SIGNALS OF STRESSWhen any of us feel stressed, our body, mind and environment give warning signals. It is important to payattention to those signals. Often, steps can be taken to calm down so those signals of stress do not buildor become overwhelming. This page talks about you, the adult, but its lessons are true of children in yourcare too.What are signals of stress? Body signals. When you are trying to understand signals of stress, ask: “What is happening in my bodythat indicates I may be becoming stressed?” You might be clenching your fists or your jaw. Maybe yourshoulders are tight. Are you pacing, or crossing your arms over your chest? Are you biting your nails?Other body signals happen inside your body. You might be sweating or turning red. Your heart might beracing. You may feel light headed or nauseous. Feeling signals. Are you suddenly expressing feelings in a negative way? Maybe you are making negativecomments about yourself (saying things like, “I am so stupid!” Or “I am no good at that!”). Are youshowing other signs that negative feelings are building inside you (such as anger or insecurity, or feelingincompetent or unloved)? Triggers. Are there certain situations that remind you of bad things that happened in your past? Doyou dislike loud noises or crowds, for example? Do you dislike being told what to do? Are there smellsor places or types of people who make you feel uncomfortable? What about seasons or anniversaries?Do you tend to be sad in April, because that’s when your beloved grandmother died or you moved awayfrom your childhood home?- 12 -

THREE TRAUMA STORIES: JOHN, SOPHIA AND HECTORTo understand more about trauma’s effect on children, read the following three stories. After each story,you will find four questions. Answer them by yourself or discuss the questions with other foster or kincaregivers, your caseworker or members of your team or family.JohnJohn’s abuse began at age 2. To discipline him, John’s father put lit cigarettes out on his body. His motherhit him with objects. In addition, John lived in a neighborhood in which he was often bullied. Older kidswould hold him and punch him over and over.At the age of 12, John was taken from his parents’ home and placed with foster parents. He often hasphysical fights at school. He has a hard time understanding and finishing his homework.Recently, John was angry with his foster mother after a family friend, who smelled of cigarette smoke,came to visit the home and wanted to shake John’s hand, even after John said no. When the foster parentraised her voice in frustration, John became furious and put his fist through a wall.John has also been in trouble at school. Recently, he was about to complete a physical fitness test. Timeran out. When he found he would not be able to complete the test, John swore at the teacher and stormedout of the classroom. As he left, he pushed a male student against the wall.Discussion questions W hat type of trauma did John experience? Was it acute, chronic or complex? I s John showing survival-in-the-moment responses of fight, flight or freeze? C ould experiences in his foster home and at school have reminded John of his past trauma experiences? A re there ways John’s behavior might have protected him in his parents’ home and community?SophiaSophia lives with her grandmother and little brother in an apartment two blocks from school. Sophia’sgrandmother often has to go to work on short notice. One night, Sophia’s aunt, the children’s usualbabysitter, was not able to help. Sophia’s grandmother asked a female neighbor who lives a couple of doorsaway to watch the children.When her grandmother got back from work, Sophia ran to her and wouldn’t stop holding on to her.Sophia’s clothes were messy and she would not talk to her grandmother or the neighbor.The family returned home and got ready for bed. Sophia’s grandmother noticed blood on hergranddaughter’s underwear. Sophia told her grandmother she had been sexually abused. Her grandmothertook Sophia to the emergency room.Lately, Sophia has been going to the school nurse. She complains of stomach pain to get out of math class.If that does not work, she simply leaves class.- 13 -

Her grandmother says Sophia does not want to go to school. She has always been a bright, hardworkingmath student. Now her female teacher says Sophia won’t participate. She isn’t doing her work. The mathteacher says they used to get along well. Now Sophia seems very afraid of her. S

Resource Guide was written by Kelly McCauley, LSCSW, with consultation from Dr. Saxe. Development of the guide was supported by the Annie E. Casey Foundation and includes work adapted from materials developed by Dr. Marion Forgatch and Dr. Glenn Saxe and adapted by Dr. Conni