Transcription

Effective Public ManagementDecember 2014Turning a Profit While Doing Good: AligningSustainability with Corporate PerformanceBy George SerafeimINTRODUCTIONThis paper seeks to shed light on an important question in 21st century capitalism. Can corporationsdo well while doing good? In other words, does a company that improves its social or environmentalperformance increase, decrease, or leave unchanged its financial performance? Adopting a longterm horizon, understanding materiality, as well as emerging regulations, societal expectations,firm innovations, and corporate governance models seem to be the answers to the conundrum.George Serafeim isthe Jakurski FamilyAssociate Professor ofBusiness Administrationat the Harvard BusinessSchoolBACKGROUND – MEASURING CORPOR ATEPERFORMANCEFor many years corporations and managers were thought to have a single objective: dowhatever is necessary, within the boundaries of the enforceable law, to maximize profits.This was consistent with Milton Friedman’s ideology around the role of the corporationin society: profit maximization.1 But which profits should a manager maximize? In other words,how should a manager decide over which time horizon she should maximize profits? Subsequentresearch made the task even simpler for managers. Under the assumption of market efficiency,where all publicly available information is incorporated in stock prices, a manager can look at thestock price and see whether she is doing the right thing. 2 Further support was provided by scholarswho argued that the stock price should be used not only as a guide for managerial decision makingbut also for incentivizing executives. 3 This completed the puzzle of ‘stock price dominance.’ If thestock price went up, a firm should be hailed. If the stock price went down, managers should befired and discipline should be exerted from the market.1 Friedman, M. 1970. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine, 32(13):122-126.2 Fama, Eugene (1970). Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work. Journal of Finance 25 (2):383–417.3 Jensen, Michael C., and Kevin J. Murphy. Performance Pay and Top Management Incentives. Journal of PoliticalEconomy 98, no. 2 (April 1990): 225–265.1

This system was as remarkably elegant as it was simple. Clarity brought by its one-dimensional objective wasits advantage. And, in some cases, it worked well as pay-for-performance schemes aligned incentives, investoractivism improved performance of badly managed firms, and board of directors supervised management moreeffectively. Perhaps not surprisingly though, this system brought excesses. Managers became obsessed withincreasing stock prices, and investors were legitimized to intervene to make sure that stock prices would continuegoing up – even if this had adverse consequences in the long-term. Corporate scandals were revealed one after theother, and accounting scandals in companies like Enron and Worldcom were becoming the standard news of theday. Well respected companies like industrial powerhouse Siemens, and defense contractor BAE Systems foundthemselves involved in bribery scandals, and oil and gas giant Royal Dutch Shell was found to have overstated itsreserves.4 Other firms laid-off thousands of people to become ‘leaner’ and thereby more profitable. Still othersmoved their operations to low-cost jurisdictions where labor costs were cheaper. Unfortunately, while movingtheir supply chains and operations, many firms adopted practices that were against the law. Some companieswere involved in child labor scandals while others bribed public officials to win contracts. Some caused majorenvironmental disasters that left local communities to pick up the pieces. Simply put, the negative effects onsociety were growing to be large while firms were pursuing ‘shareholder value maximization.’It should come as no surprise then that civil society would fight back. People demanded that corporations shouldexhibit responsibility towards society and be held accountable for their actions. Environmental concerns were atthe forefront of the debate. NGOs pressured companies to stop pollution and to tackle the ultimate common goodsproblem: climate change. With companies becoming larger and their impact on society growing, the pressureon companies to improve performance on nonfinancial dimensions increased. Consider this: in the early 1990s,there were fewer than 30 companies producing a report with environmental or social data. 5 Twenty years later,more than 6,000 companies in the world, or more than 50% of the world market capitalization, produced a sustainability report.6In the meantime, many companies experienced disruptions in their business models. The Electronic and ManufacturingServices giant Foxconn Technologies came under public scrutiny after a string of employee suicides reached theinternational press. Foxconn did not fully appreciate that advances in technology allowed fast and wide dissemination of information about what was happening inside their factories, that citizens would demand better workingconditions for the employees and that this demand for accountability would force Foxconn’s major customer,Apple, to react in order to avoid a reputational disaster. The result was a series of wage increases in Foxconnthat left the company with decreased competitiveness, a failure to uncover the true source of the problem in thefactories, and half of its market capitalization and profit margins erased.7Similarly, banking giant UBS was challenged at its core when the U.S. government launched an investigation anda legal battle against the company requiring UBS to hand in names of U.S. citizens that held secret accounts withUBS. UBS failed to appreciate citizen demand for increased transparency in business dealings and pressure on4 See for Siemens siness/21siemens.html?pagewanted all& r 0; BAESystems le/2010/02/05/AR2010020503811.html; Royal Dutch Shell landpetrol.news.5 Eccles, Robert G., George Serafeim, and Phillip Andrews. 2011. “Mandatory Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure in theEuropean Union.” Harvard Business School Case 111-120.6 A sustainability report is a firm-issued general purpose non-financial report, providing information to investors, stakeholders (e.g.,employees, customers and NGOs), and the general public about the firm’s activities around social, environmental and governance issues,either as a stand-alone report or as part of an integrated report.7 Eccles, Robert G., George Serafeim, and Beiting Cheng. “Foxconn Technology Group (A).” Harvard Business School Case 112-002, July2011.Effective Public ManagementCorporate Sustainability and Financial Performance2

governments to collect tax revenues. Under those demands, a wealth management company supported by thesecrecy laws in Switzerland would be unlikely to grow and prosper. The result was long-lasting damage in UBS’sreputation, 780 million in fines by the US government, more than 200 billion of private client assets leavingthe bank, and the governments of Germany, France, Brazil, and Canada – among many others – putting pressureon Swiss banks and the Swiss government to disclose client names.8 Perhaps not surprisingly, a few years afterUBS’s main competitor also from Switzerland, Credit Suisse, found itself in the same shoes paying ultimately 2.5billion, after pleading guilty to criminal charges.9The news was not always bad. Other companies uncovered new opportunities for value creation. Dow Chemical, anenergy intensive chemical manufacturer, reported savings of 9.4 billion and 1,800 trillion Btu between 1994 and2010 from energy efficiency programs.10 Energy intensity improved 22 percent during their first 10-year energyintensity goal (1994-2005), exceeding their 20 percent improvement target for the period. In another example, in2010, General Motors claimed to have eliminated production waste in over half of its 142 global production facilities.Waste was repurposed for productive uses such as: reconditioning oil for use in General Motors’ facilities; reusingand rebuilding wooden pallets or grinding them into landscaping chips; turning cardboard into sound-absorptionmaterial; and turning paint sludge into plastic shipping containers. General Motors claimed that since 2007 and2010, its recycling and reuse initiatives had earned the company more than 2.5 billion.11Apart from finding innovative ways to reduce costs, companies also began changing their products and servicesto meet new demands and to better serve existing ones. In 2005, General Electric (GE) launched its “ecomagination” initiative, a business strategy aimed at creating value for customers and investors by focusing on energy,efficiency, and water challenges. These products range from new types of kitchen appliances to new jet engines.GE invested 2.3 billion in the ecomagination initiative in 2011, while generating 21 billion in revenues fromecomagination products and services.12 According to its website, “Over the next five years, GE has committed togrow ecomagination revenues at twice the rate of our total company revenue, making ecomagination an evenlarger proportion of total company sales.” 13 In 2005, Nike embedded the “Considered Design” concept into itsbusiness model, with a focus on high-performing, aesthetically pleasing greener products. The goal was to drivesustainability and innovation practices in Nike’s production creation process, including assessing the entireproduct lifecycle. The structure of Considered Design was meant to cultivate innovation, with the Design teammaintaining a centralized hub that participates in key Nike functions, while responsibility was placed in the handsof individual designers. Nike believed the combination of innovation and sustainability could trigger advancesin both. Nike Flyknit technology was given as an example: “It’s a new way to knit a shoe upper out of what isessentially a single thread. It’s great for the athlete because it is lighter and offers a more custom fit. It is goodfor the planet because it drastically reduces waste from the upper production process. And shareholders benefitfrom the reduced cost of production and increased margins.” 148 Healy, Paul M., George Serafeim, and David Lane. “Wealth Management Crisis at UBS (A).” Harvard Business School Case 111-082,March 2011.9 See vasion.10 Dow Chemical annual report 2011.11 “Sustainability for Business: Innovation, Cost Savings, Opportunity,” NJPRO Foundation, April 2012. http://www.njprofoundation.org/pdf/sustain.pdf12 GE Ecomagination Portfolio, http://www.ecomagination.com/portfolio.13GE Ecomagination Portfolio, http://www.ecomagination.com/portfolio14 Nike Corporate Responsibility Report, Letter from the CEO, hapter/letter-fromthe-ceo. Accessed November 2012.Effective Public ManagementCorporate Sustainability and Financial Performance3

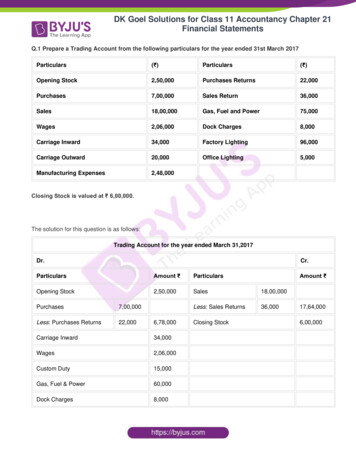

These do not seem to be isolated examples; an increasing number of firms seem willing to engage with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues that are collectively included under the umbrella of ‘corporatesustainability.’ Figure I shows the number of signatories to the United Nations Global Compact over time, a signof increasing corporate interest in sustainability.15 While joining an organization like the Global Compact couldcertainly represent a form of ‘cheap talk’ and greenwashing, it does provide some evidence of corporate interestin responsible business activities.Source: UN Global Compact https://www.unglobalcompact.org/; Eccles, Robert G., and George Serafeim. “A Tale of Two Stories:Sustainability and the Quarterly Earnings Call.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 25, no. 3 (Summer 2013): 66–77.Consistent with increasing corporate engagement with sustainability issues both the 1990s and 2000s witnesseda growth in voluntary sustainability reporting. Figure II shows the number of sustainability reports issued bycompanies over time.In parallel, sell-side analysts and investors now increasingly integrate ESG data in their valuation models.16Figure III shows the number of signatories to the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment as a signof investor interest in ESG data.17 As of 2014, asset managers and owners with more than 45 trillion in assetsunder management have committed to following the principles.While both companies and investors seem willing to accept the importance of ESG issues for business decisions,actually changing corporate and investor behavior is difficult. This is because in some cases, with the currentregulations, market logics, processes, products and business models, economic returns and better performanceon some environmental or social issue are at odds. This is not always the case though. Inefficiency occurs when a15 ‘The UN Global Compact is a strategic policy initiative for businesses that are committed to aligning their operations andstrategies with ten universally accepted principles in the areas of human rights, labor, environment and anti-corruption.’ tml16 Cheng, Beiting, Ioannis Ioannou, and George Serafeim. 2014. “Corporate Social Responsibility and Access to Finance.” StrategicManagement Journal 35 (1): 1-25; Ioannou, Ioannis, and George Serafeim. “The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on InvestmentRecommendations: Analysts’ Perceptions and Shifting Institutional Logics.” Strategic Management Journal (forthcoming).17 The United Nations-supported Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) Initiative is an international network of investors workingtogether to put the six Principles for Responsible Investment into practice. Its goal is to understand the implications of sustainability forinvestors and support signatories to incorporate these issues into their investment decision making and ownership practices. fective Public ManagementCorporate Sustainability and Financial Performance4

Source: Eccles, Robert G., George Serafeim, and Phillip Andrews. “Mandatory Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure in theEuropean Union.” Harvard Business School Case 111-120, June 2011.Source: UN PRI http://www.unpri.org/; Eccles, Robert G., and George Serafeim. “A Tale of Two Stories: Sustainability and the QuarterlyEarnings Call.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 25, no. 3 (Summer 2013): 66–77.company’s practice is both costly to it and society. For example, the inefficient use of energy raises a company’senergy costs and increases its carbon emissions; adopting a better management practice can create a benefitfor both. These situations are typically “low-hanging fruit” and, while laudable, might not have a material impacton the company’s strategy. Conversely, the company’s very business purpose produces a benefit to both thecompany and to society. While this is obvious for industries like education and health care, it applies to everysingle industry: unless some social benefit is being obtained (e.g., satisfied customers, employees with jobs, andshareholders getting a return on their money), these industries would not exist.The bigger challenges are in situations where the company benefits from a social cost when a negative externalityis being created, such as the carbon emissions produced by a utility company burning coal to provide electricityto its customers. Similarly, where companies are providing positive externalities, in the form of employee training,Effective Public ManagementCorporate Sustainability and Financial Performance5

education to local communities, or healthcare provisions, the costs to the company are obvious and immediateand any benefits are uncertain. Tough trade-offs like this are the core challenge facing companies seeking tosatisfy shareholders while responding to ever-increasing demands of other stakeholders.EXPLORING THE REL ATIONSHIP BET WEEN FINANCIAL ANDNONFINANCIAL PERFORMANCEWith companies under pressure to improve multiple dimensions of performance simultaneously, the question ariseswhether the relationship between the different dimensions of performance is positive, neutral, or negative. In otherwords, does a company that improves its environmental or social performance decrease, increase, or leave itsfinancial performance unchanged? For example, a negative relationship between financial and nonfinancial performance arises if there is a net cost in financial terms from improving nonfinancial performance. Adopting cleanerenergy technologies that are more expensive, paying employees higher salaries and providing higher benefits,introducing more expensive control and risk management systems, and avoiding growth markets becauseof corruption risks are several examples that couldWith companies under pressuregenerate this negative relationship.to improve multiple dimensionsof performance simultaneously,the question arises whether therelationship between the differentdimensions of performance ispositive, neutral, or negative.Previously, scholars within the neoclassical economicstradition argued that sustainability strategies unnecessarily raise a firm’s costs, thus creating a competitivedisadvantage vis-à-vis competitors.18 Arguing from anagency theory perspective other studies have suggestedthat employing valuable firm resources for positive socialperformance strategies benefit the manager throughreputation building but not the shareholders.19On the other hand, scholars have argued that better stakeholder relations may lead to obtaining better resources, 20higher quality employees, 21 better marketing of products and services, 22 better access to finance and lower cost18 Friedman, M. 1970. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine, 32(13): 122-126.Aupperle, K. E., Carroll, A. B., & Hatfield, J. D. 1985. An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibilityand profitability. Academy of Management Journal: 446-463.McWilliams, A. & Siegel, D. 1997. The Role of Money Managers in Assessing Corporate Social Reponsibility Research. The Journal ofInvesting, 6(4): 98-107.Jensen, M. C. 2002. Value maximization, stakeholder theory, and the corporate objective function. Business Ethics Quarterly, 12(2):235-256.19 Cheng, Ing-Haw and Hong, Harrison G. and Shue, Kelly. Do Managers Do Good with Other Peoples’ Money? (September 8, 2014).Fama-Miller Working Paper; Chicago Booth Research Paper No. 12-47.20 Cochran, P. L. & Wood, R. A. 1984. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance. The Academy of Management Journal,27(1): 42-56.Waddock, S. A. & Graves, S. B. 1997. The corporate social performance-financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal, 18(4):303-319.21 Turban, D. B. & Greening, D. W. 1997. Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. TheAcademy of Management Journal, 40(3): 658-672.Greening, D. W. & Turban, D. B. 2000. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce.Business & Society, 39(3): 254.22 Moskowitz, M. 1972. Choosing socially responsible stocks. Business and Society Review, 1(1): 71-75.Fombrun, C. J. 1996. Reputation: Realizing value from the corporate image. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.Effective Public ManagementCorporate Sustainability and Financial Performance6

of capital, 23 and to the creation of unforeseen opportunities. 24 Improved stakeholder relations could function insimilar ways as advertising does, by increasing overall demand for products and services and/or by reducingconsumer price sensitivity. 25 Moreover, it has been argued that better stakeholder relations could reduce the levelof waste within productive processes. 26 Stakeholder theory emphasizes that identifying and managing ties withkey stakeholders may mitigate the likelihood of negative regulatory, legislative or fiscal action, 27 attract sociallyconscious consumers28 or even attract financial resources from socially responsive investors. 29 In addition, stakeholder theory suggests that exhibiting social responsibility may lead to better performance by protecting andenhancing corporate reputation. 30 Finally, a number of studies within the resource-based view of the firm arguethat the mechanisms through which socially responsible behavior occur may lead to competitive advantage. 3123 Cheng, Beiting, Ioannis Ioannou, and George Serafeim. “Corporate Social Responsibility and Access to Finance.” StrategicManagement Journal 35, no. 1 (2014): 1–23.24 Fombrun, C. J., Gardberg, N. A., & Barnett, M. L. 2000. Opportunity platforms and safety nets: Corporate citizenship and reputationalrisk. Business and Society Review, 105(1).25 Dorfman, R. & Steiner, P. O. 1954. Optimal advertising and optimal quality. The American Economic Review, 44(5): 826-836.Navarro, P. 1988. Why do corporations give to charity? The Journal of Business, 61(1): 65-93.Sen, S. & Bhattacharya, C. B. 2001. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility.Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2): 225-243.Milgrom, P. & Roberts, J. 1986. Price and advertising signals of product quality. The Journal of Political Economy, 94(4): 796.26 Konar, S. & Cohen, M. A. 2001. Does the market value environmental performance? Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(2):281-289.Porter, M. E. & Van der Linde, C. 1995. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. The Journal ofEconomic Perspectives: 97-118.27 Freeman, R. 1984. Strategic Management: A stakeholder perspective. Boston, MA: Piman.Berman, S. L., Wicks, A. C., Kotha, S., & Jones, T. M. 1999. Does stakeholder orientation matter? The relationship between stakeholdermanagement models and firm financial performance. The Academy of Management Journal, 42(5): 488-506.Hillman, A. J. & Keim, G. D. 2001. Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: what’s the bottom line? StrategicManagement Journal, 22(2): 125-139.28 Hillman, A. J. & Keim, G. D. 2001. Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: what’s the bottom line? StrategicManagement Journal, 22(2): 125-139.29 Kapstein, E. B. 2001. The corporate ethics crusade. Foreign Affairs, 80(5): 105-119.30 Fombrun, C. & Shanley, M. 1990. What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of management Journal:233-258.Fombrun, C. 2005. Building corporate reputation through CSR initiatives: evolving standards. Corporate Reputation Review, 8(1): 7-11.Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., & Wicks, A. C. 2007. Managing for stakeholders: survival, reputation, and success. New Haven, CT: YaleUniv Press.31 Hart, S. L. 1995. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Academy of Management Review: 986-1014.Litz, R. A. 1996. A resource-based-view of the socially responsible firm: stakeholder interdependence, ethical awareness, and issueresponsiveness as strategic assets. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(12): 1355-1363.Rugman, A. M. & Verbeke, A. 1998. Corporate strategies and environmental regulations: An organizing framework. Strategic ManagementJournal: 363-375.Rugman, A. M. & Verbeke, A. 1998. Corporate Strategy and International Environmental Policy. Journal of International Business Studies,29(4): 819-820.Sharma, S. & Vredenburg, H. 1998. Proactive corporate environmental strategy and the development of competitively valuableorganizational capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 19(8): 729-753.Marcus, A. & Geffen, D. 1998. The dialectics of competency acquisition: Pollution prevention in electric generation. Strategic ManagementJournal, 19(12): 1145-1168.Delmas, M. A. 1999. Exposing strategic assets to create new competencies: the case of technological acquisition in the wastemanagement industry in Europe and North America. Industrial and Corporate Change, 8(4): 635.Delmas, M. A. 2000. Voluntary Agreements for the Environment: Dynamic Capabilities and Transaction Costs.de Bakker, F. & Nijhof, A. 2002. Responsible chain management: a capability assessment framework. Business Strategy and theEnvironment, 11(1): 63-75.de Bakker, F. G. A., Fisscher, O. A. M., & Brack, A. J. P. 2002. Organizing product-oriented environmental management from a firm’sperspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 10(5): 455-464.McWilliams, A., Van Fleet, D. D., & Cory, K. D. 2002. Raising rivals’ costs through political strategy: An extension of resource-basedtheory. Journal of Management Studies, 39: 707-724.Hockerts, K. 2003. Sustainability Innovations, Ecological and Social Entrepreneurship and the Management of Antagonistic Assets.Difo-Druck: Bamberg.Branco, M. C. & Rodrigues, L. L. 2006. Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics,69(2): 111-132.Effective Public ManagementCorporate Sustainability and Financial Performance7

While all the aforementionedreasons could lead to mixed results,a lack of conclusive results couldbe fundamentally attributed tothree factors: the lack of analysisof long-term effects, difficultyin identifying companies thatgenuinely commit to sustainabilityrather than greenwashing, andthe absence of an understandingof the materiality of the differentsustainability factors.When these theories were tested using archival data,scholars found contradictory evidence. 32 Such mixedresults may be attributed to existing studies “suffer[ing]from several important theoretical and empiricallimitations”33 while other scholars have suggestedthat contradictory evidence arises due to “stakeholdermismatching,”34 the neglect of “contingency factors,”35the existence of “measurement errors”36 or overall“flawed empirical analysis.”37While all the aforementioned reasons could lead to mixedresults, a lack of conclusive results could be fundamentally attributed to three factors: the lack of analysis oflong-term effects, difficulty in identifying companiesthat genuinely commit to sustainability rather thangreenwashing, and the absence of an understanding ofthe materiality of the different sustainability factors. Aswe will see below, addressing these issues reveals a much clearer picture around the performance of companiesthat develop a sustainable strategy.EVIDENCE FROM A LONG-TERM INVESTIGATIONIn a paper I co-authored with Professors Ioannis Ioannou of the London Business School and Robert Eccles ofHarvard Business School, we analyzed two virtually identical sets of firms in terms of industry membership, size,financial performance and growth prospects, of 180 US companies over the period from the beginning of 199332 Barnett, M. L. & Salomon, R. M. 2006. Beyond dichotomy: the curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financialperformance. Strategic Management Journal, 27(11): 1101-1122.Margolis, J. D. & Walsh, J. P. 2003. Misery loves companies: rethinking social initiatives by business. Administrative Science Quarterly,48(2): 268-305.Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. L. 2003. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organization Studies, 24(3):403-441.Hillman, A. J. & Keim, G. D. 2001. Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: what’s the bottom line? StrategicManagement Journal, 22(2): 125-139.McWilliams, A. & Siegel, D. 2000. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: correlation or misspecification? StrategicManagement Journal, 21(5): 603-609.Rowley, T. & Berman, S. 2000. A brand new brand of corporate social performance. Business & Society, 39(4): 397.Mahon, J. F. & Griffin, J. J. 1999. Painting a portrait: A reply. Business & Society, 38(1): 126.Roman, R. M., Hayibor, S., & Agle, B. R. 1999. The relationship between social and financial performance: Repainting a portrait. Business &Society, 38(1): 109.Griffin, J. J. & Mahon, J. F. 1997. The corporate social performance and corporate financial performance debate. Business and Society,36(1): 5-31.Ullmann, A. A. 1985. Data in search of a theory: a critical examination of the relationships among social performance, social disclosure,and economic performance of US firms. Academy of Management Review, 10(3): 540-557.33 McWilliams, A. & Siegel, D. 2000. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: correlation or misspecification?Strategic Management Journal, 21(5): 603.34 Wood, D. J. & Jones, R. E. 1995. Stakeholder mismatching: A theoretical problem in empirical research on corporate socialperformance. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 3: 229-267.35 Ullmann, A. A. 1985. Data in search of a theory: a critical examination of the relationships among social performance, socialdisclosure, and economic performance of US firms. Academy of Management Review, 10(3): 540-557.36 Waddock, S. A. & Graves, S. B. 1997. The corporate social performance-financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal,18(4): 303-319.37 McWilliams, A. & Siegel, D. 2000. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: correlation or misspecification?Strategic Management Journal, 21(5): 603-609.Effective Public ManagementCorporate Sustainability and Financial Performance8

to the end of 2010. To understand the effects of integrating social and environmental issues in an organization’sbusiness model, we first needed to identify companies that have explicitly placed a high level of emphasis onemployees, customers, products, the community, and the environment as part of their strategy and businessmodel. We used as a template a number of corporate policies identified by leading data providers (in th

1 ffectie Public anaement Turning a Profit While Doing Good: Aligning Sustainability with Corporate Performa