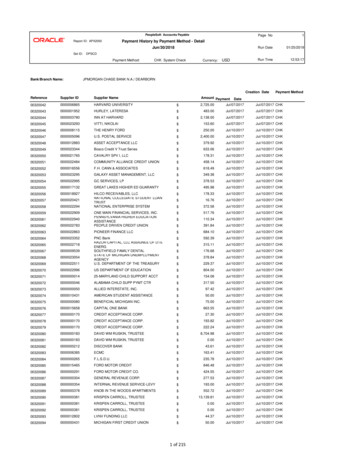

Transcription

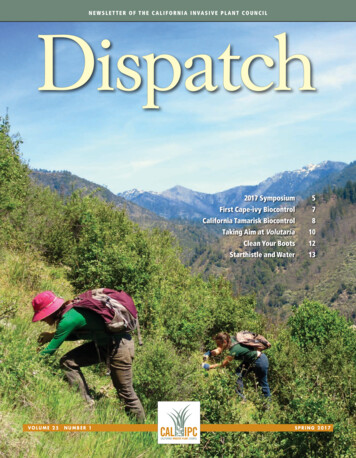

N E W S L E T T E R O F T H E C A L I F O R N I A I N VA S I V E P L A N T C O U N C I LVOLUME 25NUMBER 12017 Symposium5First Cape-ivy Biocontrol7California Tamarisk Biocontrol8Taking Aim at Volutaria10Clean Your Boots12Starthistle and Water13SPRING 2017

FROM THE DIRECTOR’S DESKNativismBy Executive Director Doug Johnson1442-A Walnut Street, #462Berkeley, CA 94709ph (510) 843-3902 fax (510) 217-3500cal‑ipc.org info@cal‑ipc.orgProtecting California’s environment andeconomy from invasive plantsSTAFFDoug Johnson, Executive DirectorAgustín Luna, Director of Finance,Operations & AdministrationBertha McKinley, Program AssistantDana Morawitz, Conservation Program ManagerMona Robison, Science Program ManagerBOARD OF DIRECTORSPresident: Jutta Burger, Irvine Ranch ConservancyVice President: Gina Darin, Cal. Dept. of Water ResourcesTreasurer: Steve Schoenig, Schoenig ConsultingSecretary: Tim Buonaccorsi, RECON Environmental, Inc.Past Pres.: Jason Casanova, Council for Watershed HealthJuan de Dios Villarino, California State ParksDoug Gibson, San Elijo Lagoon ConservancyJason Giessow, Dendra, Inc.William Hoyer, US NavyDrew Kerr, Invasive Spartina ProjectMarla Knight, Klamath National Forest (retired)Julia Parish, Catalina Island ConservancyEd King, Placer Co. Ag. Commissioner’s OfficeLaura Pavliscak, Tejon Ranch ConservancyHeather Schneider, Santa Barbara Botanic GardenBaldeo Singh, Sacramento Conservation CorpsLynn Sweet, UC Riverside Palm Desert CenterSTUDENT LIAISONSMarina LaForgia, UC DavisAmanda Swanson, UC RiversideAffiliations for identification purposes only.Cal‑IPC DispatchSpring 2017 - Vol. 25, No. 1Editor: Doug JohnsonDesigned by Melanie HaagePublished by the California Invasive Plant Council.Articles may be reprinted with permission. Previous issues arearchived at cal‑ipc.org. Mention of commercial products doesnot imply endorsement by Cal‑IPC. Submissions are welcome.We reserve the right to edit content.Follow us:On the cover:Volunteers with the Salmon River RestorationCouncil pull Italian thistle in the KlamathMountains (Photo by Emily Ferrell, from the2016 Cal-IPC Photo Contest)2Spring 2017 DISPATCH cal-ipc.orgOne of the recurring themesin critiques of invasive plantmanagement is that it is drivenby “nativism,” a prejudice against thatwhich is not native. In this time when uglyanti-immigrant sentiment is being incited,such a critique associates environmentalrestorationists with xenophobes. I evenheard an upset citizen describe invasiveplant removal as “ethnic cleansing” at anEnvironmental Commission hearing in SanFrancisco.This critique is dead wrong. Restorationists work to protect diversity, not to limit it.We work to protect native plant communities because they are rare and precious,and because they are critical to the healthof native fauna that evolved with them.There are those who point out that theaddition of naturalized non-native plants tothe native flora only increases the numberof species, one measure of biological diversity. But the relative handful of non-nativeplant species we focus on are prioritizedspecifically because they can spread extensively at the expense of other plants.These accusations tend to happen neardeveloped areas, where the management ofopen space is strongly contested. Issues likethe management of blue-gum eucalyptusstands and the use of herbicides areunderstandably divisive—cutting trees andusing pesticides cuts against the grain ofdeeply rooted environmental orthodoxy. Asone young women said at the San Franciscohearing, we’ve all read Rachel Carson, right?(And we know about the Lorax fightingdeforestation, and Erin Brockovich fightingtoxic contamination of communities.)Though some people are dead-setagainst habitat restoration and will neverbe convinced otherwise, in general it’sa good thing that residents want to usecaution before cutting trees or applyingherbicides. It’s our responsibility topresent a clear case for projects based onthorough, science-based evaluation. As wewere reminded at the March for Scienceon Earth Day, science is the systematicreduction of prejudice and bias. While wework to address the biases of others, weneed to check our own biases as well sothat charges of nativism—an unwaveringconfidence in the righteousness of favoringany native plant over any non-native plantin any situation—cannot gain a foothold.Welcome Dr. Ramona Robison!In January, we welcomed Dr. Ramona Robison to Cal‑IPC as ournew Science Program Manager, replacing longtime Cal‑IPC SeniorScientist Dr. Elizabeth Brusati, who took a position as SeniorScientist with the California Dept. of Fish & Wildlife in their InvasiveSpecies Program. Mona has over twenty years of experience in thefield. As the statewide Invasive Plant Coordinator for California State Parks she initiateda system-wide early detection and rapid response program. As a botanical consultant,she conducted rare plant surveys and wetland delineations, she helped PG&Edevelop a business-wide invasive plant strategy, and she surveyed the state for redsesbania. For her PhD in Plant Biology at UC Davis she studied Cape-ivy distributionalong the California coast, and she has served on the Cal‑IPC Board of Directors.She is currently overseeing several projects at Cal‑IPC: coordinating Volutaria control inBorrego Springs, updating our Inventory, designing research to study invasive plantimpacts on Sierra meadows, and drafting a best practices manual for organizationspreparing weed management plans. We are excited to have her join our staff!

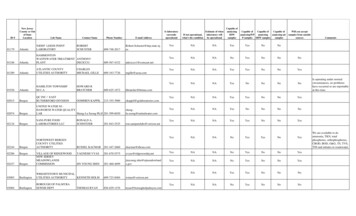

CAL‑IPC UPDATESInventory revision. We postedassessments for ten species proposed foraddition as invasive, plus risk assessmentsfor 87 naturalized species evaluated ashaving a high risk of becoming invasive.After the 60-day public comment period,we will post changes for a secondcomment period before finalizing.Arundo mapping. Our mapping team,including partners from Sonoma EcologyCenter, the Council for Watershed Health,the Cal. Dept. of Water Resources, andDendra, Inc. is halfway done mappingArundo donax at high resolution acrossthe Central Valley, using thousands ofaerial photos. The region covers some 14million acres from Redding to Bakersfield.The resulting maps of Arundo distributionwill provide a critical foundation fordesigning and implementing riparianrestoration projects.Wildland Weed NewsPlanning BMPs. Every land-managingorganization should have an invasive plantmanagement plan for their lands (andwaters). The US Fish & Wildlife Serviceis contracting with Cal‑IPC to developa manual covering best managementpractices (BMPs) tohelp organizationscraft strong plans.We have conveneda technical advisorycommittee, and arecollecting examples ofplans to draw from.The manual will becomplete in 2018.Volutaria control.Cal‑IPC receiveda grant from theNational Fish &Wildlife Foundation(NFWF) to controlVolutaria tubuliflora,a new Mediterraneanweed that threatensto spread across theAmericansouthwest.Story on page 10.Illustration by Ryan Jonesin the desert, in Palm Springs,Oct. 24-27. See pages 4 and 5 formore information about our 25thSymposium last year and aboutthe upcoming 2017 Symposium.Limonium control. Cal‑IPChas NFWF funding to controlinvasive sealavender (Limoniumramosissium and L.duriusculum) in SanFrancisco Bay saltmarshes. Our secondseason at 13 sites isunderway. Story in theFall 2016 Dispatch.Sierra meadows.Cal‑IPC is developinga rating system togauge vulnerabilityof Sierra meadowsto impacts frominvasive plants. Weare also developingBMPs to preventVolutaria bolting above desert wildlfowers,weed spread duringincluding desert dandelion, sand verbena,hydrologic restorationand Cryptantha.of meadows, and research designs forgauging the impact of invasive plantson wildlife, water, and carbon in Sierrameadows.Pat Matthews2017 Symposium. We will beVolunteer training. Cal‑IPC hasorganized four workshops around the SFBay Area this summer to train volunteerson invasive plant management andprovide networking opportunities for localwatershed groups working on weeds.See page 16.OTHER NEWSMichelle ForysEnglish ivy petition. Twentyorganizations from the north coast,including the BLM, Sierra Club, and YurokTribe, have petitioned the Cal. Dept.of Food & Agriculture to list English ivy(Hedera helix) as a noxious weed based onEnglish ivy covers forest understory at Trinidad State Beach in Humboldt County.(Continued on page 14)cal-ipc.org DISPATCH Spring 20173

Invocation to Cal‑IPC’s 25th SymposiumEditor’s Note: Garrett Dickman is Restoration Ecol‑ogist at Yosemite National Park, where he overseesinvasive plant management work that interfaceswith fire management, cultural resource manage‑ment and recreation. He is a longtime memberof Cal‑IPC, and he was a major contributor to ourprevention best management practices manualsand videos. He also helped set up our 25th An‑niversary Symposium last fall at the Tenaya Lodgenear Yosemite. Some of us attended his fieldtrip, and along with fascinating ecology we alsolearned about climbing El Capitan and other hugerock faces in the park. His connection to the placegoes much deeper than employment. So it’s notsurprising that when we invited him to open theSymposium by welcoming us to Yosemite he wentdeeper, providing a moving personal testimony tothe work we do. We reprint his welcome here.WGarrett leading a field trip discussing the restoration history of Yosemite Valley.If you’re a casual observer of the naturalworld, you have heard or contributed tothe near fever pitched collective cry coming from the conservation communities.The trees are dying and the sky is falling,or at least becoming increasingly ladenwith CO2. There hasn’t been that muchCO2 in the atmosphere since the Pliocene,when camels walked around the BerkeleyHills and the seas were 30 meters higher.We’ve entered a new epoch. That is ageologic term for what is really a biologicevent. Admittance doesn’t come easy, butour communal love of burning decomposed dinosaurs has paved the way. It’salso partial acknowledgement that we’veBob Caseelcome to the 2016 Cal‑IPCSymposium. Allow me to brieflyperch on a soapbox and reinforce that you are doing some of theworld’s most important work—protectingbiodiversity—and also to introduce theidea that you may not want Millennials tospeak in front of large audiences (thoughage being what it is, you might be stuckwith us). So, I apologize, because as ascientist born in the 80s and growing upon a steady diet of The Onion and The FarSide, I must spend a little time wallowingas I rattle my pom-poms at you.Doug JohnsonGarrett Dickman,Yosemite National ParkEvening socializing around the campfire at Tenaya Lodge during Cal-IPC’s 2016 Symposium.4Spring 2017 DISPATCH cal-ipc.orgcreated the 6th major extinction event inearth’s history. Welcome to the Anthropocene.In reading the World Wildlife Fund’s“Living Planet” report, the world hasbeen emptied of almost 2/3 of its vertebrate animals since 1970 (to clarify, that’sindividuals, not species). The freshwatersystems have declined 81%, terrestrialsystems by 38%, marine systems havestabilized to a 36% loss. Coral reefs havedeclined by 75%, and 87% of the world’swetlands are lost.If you were alive in the 1970s yourworld was more magical than someoneborn this year will ever experience. Wenow have less than half as many antelopegalloping across the plains, less than halfas many whales migrating up and downthe coastlines, less than half the chorus offrogs. The flocks, the herds—they’ve beenthinned, hunted, eaten, turned into hats,their homes destroyed and paved over.Why should people care? Why is thisbiodiversity so important?Imagine that species are the parts of aplane, soaring through the sky that we’reall aboard. Take pieces off at random:you’ll find most are connected.Maybe you dismantle a screw on a turbine, maybe an elevator. Maybe you takeout a bag of peanuts. Eventually, you’ll(Continued on page 6)

2017 Symposium in Palm Springs, October 24–27Join us in the desert this year to catch upon the latest in invasive plant science andmanagement! Our program includes talks,posters, trainings, discussion groups andfield trips on projects addressing invasiveplants from riparian, grassland, mountain,coastal, and aquatic/wetland habitats.Attendees will share information abouteffective tools, relevant research, nonchemical management approaches as wellas the latest on herbicides. We will discussthe importance of engaging diverse communities, ways to incorporate traditionalecological knowledge into management,and the roles botanic gardens can play inaddressing invasive plants.Palm oasis in Coachella Valley, CAWe’ll be at the Riviera, the fabledhangout for Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis,2. Coachella Valley Preserve (half day)Jr., Dean Martin and the rest of the Rat—invasive plant management andPack. A recent review by SFGATE says itresearch to protect sand dune andhas a “playful, plush vibe (with) retro furoasis habitats with endangered species.niture and cheeky postmodern décor ”3. Whitewater Preserve (full day)—With three pools, six restaurants andinvasive plant management in a richbars, and warm desert air, it’s bound toriparian habitat protected within thebe a good spot for decompressing after aSan Gorgonio Wilderness.busy field season.REGISTRATION:PRE-SYMPOSIUM TRAININGS:Registration includes the DPR Laws &1. Invasive Plant Management 101Regs session Oct. 24 and all sessions(half day)on Oct. 25-26. Registration includes all2. Calflora Mapping Tools (half day)meals Oct. 25 and breakfast on Oct. 26.Additional costs: trainings on Oct. 24FIELD TRIPS:1. Joshua Tree National Park (full day)— are 50; field trips on Oct. 27 are 25invasive plant management in context half-day, 50 full-day; box lunch for thewith wildfire, nitrogen deposition, and Career Panel on Oct. 26 is 25 for nonstudents (students’ lunches are covered).historic landscape preservation.Cameron Barrows“WORKING ACROSS BOUNDARIES”Members: 320 early-bird 345 after Sept. 1 370 after Oct. 15Non-Members: 370 early-bird 395 after Sept. 1 420 after Oct. 15Students: 50 early bird 65 after Sept. 1 80 after Oct. 15(Students receive one-year membership.Students must be enrolled in a degreeprogram or have graduated in the last year)Symposium volunteers: 220 while they last (Requires 4 hourshelp with registration, session timekeeping and other tasks.)Bob CaseLODGING:We have negotiated the State per diemrate of 95 for our room block at theRiviera Palm Springs! Use the link on ourwebsite to make your reservation. Rateavailable through Oct. 2, so make yourreservation early.A great opportunity to network, learn, and celebrate!Visit cal-ipc.org to register, makereservations at the Riviera, and getother Symposium information.cal-ipc.org DISPATCH Spring 20175

take off a piece, or enough pieces, whereyou break something important and theplane spirals down. It’s anybody’s guesswhat’s truly important or not, consideringno one knows what makes this plane fly,let alone what most of the pieces are orhow they are connected.You already know this. We messed up.This is a crummy experiment.Instead, imagine standing in a field ofpoppies next spring. The wind rustlesthe leaves, the ground is dewy and therobins sing each to each other, the airreeks of life.You can intangibly feel the biodiversityand you can imagine this, because you’vebeen there, or been someplace similar. Youstill get to have that experience, becausesomeone fought for that land and thosespecies to be protected. What if future generations can’t enjoy such simple delicacies?Now picture yourself in a field of corn.The wind blows through the leaves, acrow squawks. I like corn, nothing wrongwith corn, but that’s about it. The crowand the corn. It lacks the intangible andis the outdoor equivalent of cubicle wallsI have known so well.For me, the importance of protectingthe pieces I didn’t think I cared about camewhen I was at Julia Pfeifer State Park at BigSur and was buzzed by a California condoren route to engorging itself on a dead sealpup. I had previously thought that all thefuss and expense for saving a buzzard wasridiculous. That is, until I was buzzed byPleistocene-era megafauna. It was worthevery penny and more.Not far from here is the Mariposa Groveof Giant Sequoias. Galen Clark and JohnMuir came upon them, wrapped their armsaround those big trees, and said “We willprotect these. This is bigger than me.” Itstill is and those trees still are. They standtoday as they did then, and as they will.That reach has extended around the world.The people of this world have figured out away to protect the most iconic natural features on this planet starting with a simplehug of a tree. America’s greatest idea hasbeen embraced world-wide.California and its many protected landsmeans so much to so many people, es6Spring 2017 DISPATCH cal-ipc.orgInvasive plant management is the sweetspot in biodiversity protection. There aremany stressors to species we don’t knowhow to fix, like climate change or nitrogendeposition. But we do know how to battleinvasive plants, we’re good at it, and we’regetting better at it all the time. Invasive plantmanagement protects biodiversity now andprovides resistance and resilience to thelandscape in the future so that managers ofthe future are not completely flat-footed.Athena Demetry of Yosemite National ParkCalifornia is the place where cuttingaccepting the Golden Weed Wrench Awardedge invasive plant management andfor Land Manager of the Year from Cal‑IPCnative species restoration is happening.Executive Director Doug Johnson.Where we have complete floristic inventopecially Californians. California has spent ries, where science guides management. Itis the people in this room, it is the peoplemore than any other state on conservaat Cal‑IPC, CalFlora, CNPS, land managtion and land protection.ersin the Park Service, the Forest Service,People come from all over earth tothe many forward-thinking ranchers andvisit. They save every last penny to drivefarmers, utilities commissions, and theto see Half Dome, the redwoods, thesuperbloom. They want to see California’s universities that make this happen. Wefabled shorelines, mountains and deserts. give other land managers across the USand world a model they can look to. ToBiodiversity is part of our identify.show that it can be done.The California Floristic Province is oneLook at the agenda. You are the onesof 35 biodiversity hotspots worldwide.whogive future generations the opporBy definition, a hotspot has an unusuallyhigh number of unique flora and has lost tunity to experience that moment whenat least 70% of the original habitat. They the temperature rises on a cool springmake up 2.3% of the earth’s surface, but morning and the poppies suddenly burstopen. The world needs to know thatprotect 50% of the earth’s plants and42% of the vertebrates. This land of pop- places and species can be protected.Yosemite is emblematic of that idea andpies, tiger salamanders, and Joshua treesis proof that we can protect these placesis distinctly recognized for its importancedue to the high plant diversity. Over 5,000 and all that’s in them for over 100 years,and we will protect them for future genspecies of plants, and 37% are endemic,erations. We are every bit in the businessgrowing nowhere else.of creating hope as much as we are theI will say with hope, the National Parkbusiness of protecting the sacred.concept and the concept of protectingThank you all for being here. Thankland works. Very little loss of biodiversityyoufor all that you do. Welcome tooccurs once these lands are protected andCal‑IPC’s2016 Symposium.managed.It is not enough to merely put your armsCongrats to our Student Winners!around a place and protect it. The bigBest Paper—Daniel Winkler, UCgest threats to biodiversity worldwide areIrvine, “Using population genomicshabitat loss, fragmentation, overharvesting,to uncover the rapid colonizationand non-native invasive species. There isof Sahara mustard (Brassicaoccasional public outcry when a new parktournefortii) in the United States.”ing lot goes in, but few see a field of nativeBest Poster—Michala Phillips, UCwildflowers slowly transition into annualRiverside, “Do invasive grassesgrasses and know what happened. Theyemploy different water use andjust know it’s less pretty. It’s a fight thatrooting strategies than a nativemany don’t see, don’t know what to lookchaparral shrub?”for, and don’t know its importance.Bob Case(Continued from page 4)

First biological control agent released against Cape-ivyCCourtesy of USDA ARSape-ivy (Delairea odorata, Asteraceae) is one of the worst invasiveweeds in California (rated “High”by Cal‑IPC and listed by the state as anoxious weed), colonizing riparian, forest, and scrub habitats along the California coast and East Bay hills. Cape-ivycan smother native oaks and other trees,displace native herbs and shrubs, andclog water flow along freshwater creeks.To protect these habitats, federal, state,and local natural resource agencies, withthe help of thousands of volunteers,have spent a lot of time and money onherbicide treatments and hand-pulling inattempts to remove Cape-ivyResearch into the potential of an effective and safe biological control agentbegan in the late 1990s, when now-retired entomologist Dr. Joe Balciunas foundseveral insects feeding on Cape-ivy in theplant’s native range in South Africa. Afteryears of host-specificity testing and environmental permitting, with support fromCal‑IPC, the USDA-Agricultural ResearchService (USDA-ARS) in 2016 began releasing a shoot tip-galling fly, Parafreutreta re‑galis (Diptera: Tephritidae) to help controlthe spread of Cape-ivy.Female flies produce galls in Cape-ivyshoot tips by laying their eggs inside thestems. Each female lays dozens of eggsCape-ivy infestation at Morro Bay State Park.on multiple shoot tips during her 2-weekadult lifespan. Eggs hatch into larvaewhich live inside and feed on the galltissue for four to six weeks as the gallexpands. Larvae chew small ‘windows’ inthe galls before pupating. One to threeweeks later, adult flies emerge. Adult fliesthen repeat the life cycle. Impact testsshowed that the fly reduced the stemlength and biomass of potted Cape-ivyby 30-60% after just one generation.Like other biocontrol agents, they do noteliminate their host plant, but they havethe potential to significantly reduce it.Host-specificity testing was conductedby the USDA-ARS Exotic and InvasiveWeeds Research Unit Quarantine Laboratory in Albany, CA, with complementarywork by the South African AgriculturalResearch Council-Plant Protection Research Institute. Host range tests covering 99 other plant species showed thatP. regalis produced galls and developedsuccessfully only on Cape-ivy. Other plantspecies tested included 42 native species and non-native crops in Asteraceae,including California Senecio and Packeraspecies. Major habitat associates fromother plant families were tested as well.In 2013, an application for a permitto release the fly was submitted to theUSDA-Animal and Plant Health InspectionService (USDA-APHIS),and was subjectedto peer review by apanel of experts fromthe U.S., Canada, andMexico. The panel recommended release ofthe fly. Subsequently, aBiological Assessmentwas prepared, whichreceived concurrencefrom the U.S. Fishand Wildlife Service,and an EnvironmentalAssessment was pre-S. Portman, USDA-ARSPatrick J. Moran and Scott L. Portman, USDA-ARSExotic and Invasive Weeds Research UnitFirst galled shoot tip observed in the field inCalifornia, November 2016, at a site in SonomaCounty.pared for NEPA (National EnvironmentalProtection Act) compliance. USDA-APHISissued a release permit in May 2016. Currently, hundreds of flies are being produced in cages outside of quarantine atthe USDA-ARS facility in Albany CA.To date, P. regalis has been releasedat seven sites, ranging from southernSonoma County to the Big Sur area inMonterey County. Cooperating landowners include the East Bay RegionalPark District and several private landowners. Releases are being followed upwith visits every few weeks to monitorgall formation, establishment of the fly,and eventually, dispersal and impact ofthe flies on Cape-ivy populations. Lastweek, the first open field-produced gallwas documented at a site in SonomaCounty. Monitoring of existing releasesites will continue throughout the wintermonths. Additional releases will bemade next spring and summer as Capeivy produces new shoot tips.New release sites for the spring andsummer of 2017 are still being sought,especially from Humboldt County to Ventura County (areas of heaviest Cape-ivyinfestation). Public or private landownersinterested in releases of P. regalis on theirproperty are encouraged to contact Dr.Patrick Moran (Patrick.Moran@ars.usda.gov) for more information.cal-ipc.org DISPATCH Spring 20177

Alliance forms to guide tamariskbiocontrol in CaliforniaNicole Norelli, Riparian Invasion Research Lab (RIVRLab), UC Santa BarbaraEditor’s Note: You have probably heard aboutthe tamarisk beetle, one of the most effectivebiocontrol agents released in recent years. (Soeffective, in fact, that it has engendered contro‑versy over potential impacts to the endangeredsouthwestern willow flycatcher by damagingtamarisk that the bird has come to depend onin the absence of native willows.) Originallyreleased in several western states, the beetle hasnow made its way into California. While debatecontinues about tamarisk impacts on wateravailability and endangered species habitat alongwestern waterways, a new alliance of partnersis working to address how we can best benefitfrom the evolving situation here in California.Isystem where successive generationsdispersed from southern Utah to LakeMead, and then, following the ColoradoRiver, they reached southern Californiain 2015. First detections were in theMohave Valley using traps baited with asynthesized aggregation pheromone. In2016, Diorhabda was established withinthe state with major defoliation oftamarisk in the Needles region and surrounding Lake Havasu, as well as alongthe Mojave River near Barstow. Anotherpopulation exists further north on theOwens River, presumably establishedfrom original research releases there in2001. In addition, a related species, theMediterranean tamarisk beetle, Dio‑rhabda elongata, was later released andTom Dudleyn 1998, the northern tamarisk beetle(Diorhabda carinulata) from centralAsia was approved for release tocontrol tamarisk or saltcedar (Tamarixramosissima, T. chinensis and hybrids) inseveral western states following a decadeof testing overseas and in U.S. quarantinefacilities to ensure host specificity andefficacy. Since its introduction, the beetlehas proven successful in suppressing theinvasive target plant north of about 38 Nwhile further south the daylength cuethat induces beetles to enter diapause(insect-style hibernation) comes too earlyfor successful over-wintering.Rapid evolution in this developmental trait, however, allowed beetles tostay active later in the season and thusfacilitated their expansion southward, asdocumented by Dan Bean at the Colorado Department of Agriculture. This wasparticularly apparent in the Virgin RiverTamarisk defoliation along the Colorado River near Needles, CA.8Spring 2017 DISPATCH cal-ipc.org

Tom DudleyBruce Kenyon (Quail Unlimited) and Alliance partner Mike Pitcairn (California Department of Food &Agriculture) in front of beetle defoliation at Camp Cady at the Mojave River.It is relevant to note that thereremains an active lawsuit filed by theCenter for Biological Diversity to haltthe tamarisk biocontrol program overperceived risks to nesting endangeredTom Dudleyis weakly established in the northernCentral Valley where it primarily feedson a tamarisk species (T. parviflora) alsofrom the Mediterranean region.Now that the beetle has enteredsouthern California, the California Alliance for Tamarisk Biocontrol (CATB)has been established to provide guidance to the biocontrol program in thisstate. CATB was formed with supportfrom Cal-EPA Department of PesticideRegulation as a means to reduce herbicide use by promoting natural controlmethods, and is comprised of experts inthe fields of biocontrol, invasive speciesmanagement, endangered species protection, and ecosystem restoration. TheAlliance mission is to connect with interested stakeholders in watersheds acrossthe state to identify candidate sites forbiocontrol implementation, assist in newbeetle releases, and to develop a standardized monitoring protocol for monitoring beetle establishment and ecosystem responses. Partners are developingguidelines for determining whether andhow to apply restoration methods topromote recovery of native vegetation,and also developing outreach materials to inform the public through variousmedia of the benefits and real, albeitminor, risks of tamarisk biocontrol. TheAlliance will also be monitoring movement of the beetles using sentinel trapsto detect their arrival in new areas.The feeding action of Diorhabda larvaeand adults results in host plant defoliation and dieback as stored metabolitesare incrementally depleted followed bysubstantial plant mortality after 3-4 yearsin some areas. Loss of foliage reduceswater losses to transpiration, and innorthern Nevada, leads to groundwater savings of roughly 2,500 acre-feetannually. In the warmer conditions ofsouthern California, even greater waterconservation may be achieved. Birdsand other wildlife have been observedfeeding on the beetles themselves, andthere is early evidence that reduction incompetition from tamarisk is allowingreturn of native riparian plants, presumably to be followed by fauna that favorthe native vegetation.Sticky trap with male-derived aggregationpheromone for Diorhabda. These sentinel trapsare broadly distributed to detect colonizationas the beetles move into new regions. Thepheromone, which is produced at our UCSB lab,is also used to retain beetle populations at thesite where they are re

Spring 2017 DISPATCH. cal-ipc.org. 1442-A Walnut Street, #462 Berkeley, CA 94709 ph (510) 843-3902 fax (510) 217-3500. cal-ipc.org info@cal-ipc.org. Protecting California’s environment and . economy from invasive plants. STAFF. Doug Johnson, Executive Director Agustín Luna, Director of Fin