Transcription

ADVANCINGMEN’S REPRODUC TIVEHEALTHIN THE UNITED STATESCurrent Status and Future DirectionsSummary of Scientific Sessions and DiscussionsSeptember 13, 2010Atlanta, Georgia

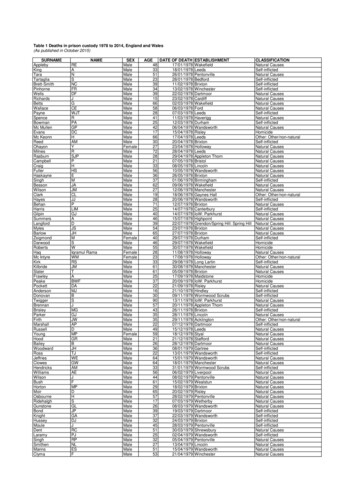

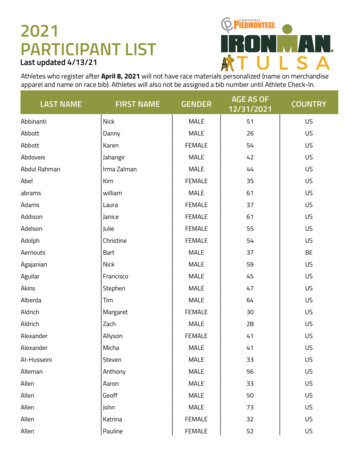

Table of ContentsIntroduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Agenda . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7Summary ReportOverview of Chronic Disease Prevention, Health Promotion and Reproductive Health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Overview of Men’s Reproductive Health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10CDC’s Past and Current Men’s Reproductive Health Activities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11CDC’s Sexual Health Activity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Comprehensive Reproductive Health Services for Men Visiting STD Clinics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14Overview of Male Contraception . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15Overview of Male Infertility . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17Fertility Preservation in the Male Patient with Cancer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18Modifiable Lifestyle Issues and Male Reproductive Health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20Mental Health Issues in Male Reproductive Health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22The Importance of Men’s Reproductive Health on Women’s Health and Fertility . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23Involving Men in Reproductive Health and Family Planning Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24Panel Perspectives on Men’s Reproductive Health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25Attachment 1 Registrants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .32Attachment 2 References Cited by Presenters and Others . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .41Advancing Men’s Reproductive HealthSummary of Scientific essions3

IntroductionThis report contains a summary of presentations and discussions from the meeting, “AdvancingMen’s Reproductive Health in the United States: Current Status and Future Directions .” Themeeting was originally planned to help CDC staff and our Federal colleagues gain insights intothe emerging areas of public health activities related to male reproductive health .What began as a “brown bag” seminar for CDC staff quickly developed into a one-day meeting of scientists,program managers, and clinicians . Through word-of-mouth, the Meeting Planning Committee received emailsand calls from professionals asking to be included as attendees . Many understood neither CDC nor other Federalagencies could offer any form of travel reimbursement or subsidy . With the assistance of CDC staff members,the meeting venue and logistics were changed to accommodate almost 100 people within less than 4 weeks .Since the meeting, many have requested a meeting summary that could be shared with other publichealth professionals . The Meeting Planning Committee requested this document be prepared for widerdistribution and use . Thanks to the cooperation of speakers and others, this document was prepared .An electronic version of the report is scheduled for release at www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth .Questions concerning the Report, the 2010 meeting, or other matters relatedto this work are welcomed . Inquiries should be addressed to:Men’s Reproductive Health ActivitiesCDC Division of Reproductive Health4770 Buford Highway, MS K-20 (LW)Atlanta, GA 30341Telephone: 770-488-5200Fax: 770-488-6450Email: drhinfo@cdc .govImportant Information:The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Chronic DiseasePrevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP), Division of Reproductive Health (DRH) supported thepreparation of these proceedings using notes and documents obtained from meeting speakers andpresenters . The views or opinions presented in this should not be construed as the official policiesof the U .S . Department of Health and Human Services and its agencies (including CDC) .Notes to Readers: Technical and scientific concepts presented by speakers required the useof terms that may be considered, by some, to be explicit . Some information presented used information available at the time of the meeting . This documentshould be considered a historic context for future discussions of male reproductive health . The findings and recommendations presented do not reflect commitment ofDHHS and its agencies to provide support for specific public health activities .4Advancing Men’s Reproductive HealthSummary of Scientific essions

U.S. Department of Health and Human ServicesCenters for Disease Control and PreventionNational Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health PromotionDivision of Reproductive HealthADVANCINGMEN’S REPRODUC TIVEHEALTHIN THE UNITED STATESCurrent Status and Future DirectionsSeptember 13, 2010Atlanta, GeorgiaSummaryThe “Advancing Men’s Reproductive Health in the United States: Current Statusand Future Directions” meeting was convened by the U .S . Department of Healthand Human Services (HHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC), National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion(NCCDPHP), Division of Reproductive Health (DRH) . The meeting was heldon September 13, 2010, at the CDC Roybal Campus in Atlanta, Georgia .

AgendaADVANCINGMEN’S REPRODUC TIVEHEALTHIN THE UNITED STATESCurrent Status and Future DirectionsSeptember 13, 2010Atlanta, Georgia8:00WelcomePeter Briss, MD, MPH8:10Meeting Process and ObjectivesElizabeth Martin, Meeting Facilitator8:20Overview of Male Reproductive HealthDennis Fortenberry, MD, MS8:50CDC Activities Related to Male Reproductive HealthPast and Current Activities—Lee Warner, PhDNew Directions: Sexual Health—John Douglas, MD9:10HIV/STD PreventionCornelis (Kees) Rietmeijer, MD, PhD9:30Break9:45Male ContraceptionAjay Nangia, MBBS, FACS10:05Male Factor InfertilityLawrence Ross, MD10:25Fertility Preservation in the Male Patient with CancerRobert Brannigan, MD10:45Modifiable Lifestyle IssuesStanton Honig, MD11:05Mental Health IssuesWilliam Petok, PhD7

Afternoon session12:25Introduction to Afternoon SessionMaurizio Macaluso, MD, DrPH12:30Involving Men in Reproductive Health and Family Planning ServicesRoy Jacobstein, MD, MPH12:50Perspectives— A Panel DiscussionScott Williams, Men’s Health Network, Introductions and PurposePanelists:Lynn Barclay, American Social Health AssociationKen Mosesian, The American Fertility AssociationBarbara Collura, MA, RESOLVEJoyce Reinecke, JD, Fertile HopeScott Williams, Men’s Health NetworkPaul J . Turek, MD, American Society of AndrologyLawrence Ross, MD, American Urological Association and AUA FoundationDolores Lamb, PhD, American Society for Reproductive Medicine82:00Break2:20Afternoon Discussion Sessions:Gaps in Research or PracticeAdvancing Men’s Reproductive HealthGroup FeedbackMeeting Outcomes and Next Steps4:45Closing SessionAdvancing Men’s Reproductive HealthSummary of Scientific essions

WelcomeMs . Martin reminded participants that 12 scientificpresentations would present information on the statusof several key areas of men’s reproductive health .Peter Briss, MD, MPHMedical DirectorCenters for Disease Control and PreventionNational Center for Chronic Disease Preventionand Health PromotionOverview of Chronic DiseasePrevention, Health Promotionand Reproductive HealthDr . Briss opened the meeting by welcoming theparticipants on behalf of CDC and its National Centers,Institutes, and Offices . He confirmed that CDC wasextremely pleased with the high level of involvement andenthusiasm among participants . Dr . Briss also stated thatCDC was honored to host a meeting highlighting issuesrelating to men’s roles in reproductive and sexual health .Maurizio Macaluso, MD, DrPHChief, Women’s Health and Fertility BranchCenters for Disease Control and PreventionNational Center for Chronic DiseasePrevention and Health PromotionDivision of Reproductive HealthDr . Briss announced that the content of the meetingwould target two of six “Winnable Battles” identifiedby Dr . Thomas Frieden, director of CDC, as publichealth priorities: HIV prevention and prevention ofunintended adolescent pregnancy . He also informedthe participants that the Adolescent meeting wasexpanded beyond the initial focus on male infertilityto a wider discussion of the current status of scienceand practice regarding men’s reproductive health .(Note: Dr. Macaluso, at the time of thispresentation, was a federal employee. See theRegistrant List for additional information.)Dr . Briss concluded his opening remarks by thankingthe participants for contributing their valuable timeto attend the meeting and provide CDC with theirexpertise . He confirmed that CDC looked forward tothe outstanding input and insights the participantswould provide over the course of the meeting toadvance the field of men’s reproductive health .Elizabeth A. MartinPresident, Elizabeth A . Martin and AssociatesMs . Martin served as the facilitator of the meeting andjoined Dr . Briss in welcoming the participants to themeeting . She explained that the Planning Committeedeveloped three objectives for the meeting: Provide a greater understanding of the scope andnature of men’s reproductive health (MRH) throughpresentations and discussions on the publichealth aspects of preventing, treating, and caring forconditions affecting reproduction and sexual health . Identify gaps in reproduction and sexual healthresearch, health care services, and public healthprograms, especially when these gaps couldsustain disparities or undue burdens on MRH . Identify future directions for effective ongoingpartnerships among public health officials, healthconsumers, scientists, academic organizations,and others concerned with the status of MRH .Advancing Men’s Reproductive HealthDr . Macaluso explained that reproductive health plays animportant role in chronic disease prevention and healthpromotion . The Greek physician, Soranus of Ephesus,first introduced the term “chronic disease” in the secondcentury AD as “those long diseases.” A more moderndefinition characterizes chronic diseases as having amultifactorial etiology, long induction time, and longduration of disease that may or may not be reversible .The conceptual framework for reproductive healthis similar to that used for chronic diseases, in that itinvolves complex interactions among genes, socialenvironment, infections, and human behavior; the lifespanfrom preconception through menopause and beyond,including trans-generational effects; and specific chronicdiseases (e .g ., infertility, HIV/AIDS, cancer, diabetes) .The concept of health promotion is extremely relevantto reproductive health . The modern definition of“health promotion” is a focus on changing lifestyleand environment to achieve optimal health . “Optimalhealth” is defined as a broad and complex entity thatincludes a balance among a number of dimensions,such as physical, emotional, social, spiritual, andintellectual health . The focus on optimal health isimportant to reproductive health issues, includinggender and social equity in health, optimal familyplanning, safe motherhood, and healthy babies .A focus on reproductive health can play a critical rolein chronic disease prevention and health promotion byproviding strong theoretical models for causation andprevention, a life stage when exposures can be effectivelymodified, impact on nonreproductive outcomes, andintegration of efforts to reduce health disparities .Summary of Scientific essions

Dr . Macaluso explained that the morning presentationswould describe ongoing and completed MRHresearch and other activities both within CDC andin the field . Although these topics are relevant toMRH and were selected to stimulate discussionamong the participants, these issues would notfully cover the complex and broad field of MRH .CDC would rely on the expertise of the participantsto build a more comprehensive list of MRH topics,identify gaps in existing knowledge, proposestrategies to effectively apply science to improvethe reproductive health of men, and recommendapproaches to promote MRH at the national level .Overview of Men’s Reproductive HealthJ. Dennis Fortenberry, MD, MSProfessor of Pediatrics and Associate DirectorAdolescent Medicine SectionIndiana University School of MedicineDr . Fortenberry reported that four concepts areextremely important to MRH: (1) consider theessential distinctions between men’s and women’sreproductive health; (2) respect, but not worshipbiological essentialism; (3) broaden the parameters ofMRH; and (4) take a lifespan perspective on MRH byconsidering its intersection with women’s reproductivehealth . Factors in MRH differ over the lifespan ofboys, teens, emerging adult males 18–26 years ofage, middle-aged men, and older adult men .Gender plays an important role in clearly identifyingand characterizing “males” with respect to MRH .Data collection was recently completed for astudy with 80 bisexual men in Indianapolis . Forpurposes of the study, “bisexual behavior” wasdefined as men who had sex with at least oneman and one woman over the past 12 months .Of all men included in study, 50% had childrenand 25%–30% of this subgroup had 2 children .These men reported the difficulties in navigatingtheir dual roles as fathers and bisexual men . Gay andbisexual men are included in HIV and STD studies,but are typically excluded from MRH research .Gender has both biological and cultural properties .In terms of the biological aspects of gender, the 2006Bartlett and Vasey study analyzed gender-atypicalbehavior that was recalled among fa’afafine, men, andwomen in Samoa . Fa’afafine are biological males bornto mothers who already have at least one son . The studyindicated that fa’afafine undertook gender-atypicalrole preferences as children . As a result, these malesidentified a preference for female-typical behavior,10preferred to play with girls, and had an interest in girl’stoys, games, and makeup at the same level as females .The study further suggested that adult fa’afafine oftenengaged in same-sex relationships, but a fair numberof these men also had relationships with women andproduce children . Overall, gender has essential aspectsin the composition of humans, but is not limited togenes inherited at the time of conception . The studydemonstrated that gender may be influenced bynon-genetic factors, including those associatedwith intrauterine environment .As an example of cultural aspects of gender, malesare not “biologically required” to stand whileurinating . However, this behavior is associated withmasculinity and is extremely difficult to changefrom both cultural and societal perspectives .Circumcision also is a source of longstandingscientific, social, and cultural debate regardingits importance to both public health and men’shealth . However, further research is needed tobetter understand the reasons why circumcisionplays such a critical role in men’s health .Well-designed studies have demonstrated thatcircumcised men have a substantially lower riskof acquiring HIV if exposed . Recent researchshowed that circumcision significantly changedthe microbiology of the coronal sulcus and made itless susceptible to HIV when exposed by modifyingthe microbial communities that are present .The 2010 Price, et al . study analyzed the effects ofcircumcision on the penis microbiome in adult menin East Africa both pre- and post-circumcision . Thestudy showed significant decreases in clostridialesand Prevotellaceae and also found an associationbetween bacterial vaginosis in women andseveral genera, including Anaerecoccus, Finegoldia,Peptoniphilus, and Prevotella . The Price studyfurther indicated a potential intersection betweenmen’s and women’s reproductive health .A study conducted in Indianapolis in adolescentcircumcised and uncircumcised males 18 years of agedemonstrated a similar shift in microbial populationsusing coronal sulcus swabs and urine . For example,circumcised adolescent males had much lessStaphylococcus and Prevotella than uncircumcisedmales, while circumcision had no effect in theexchange of Lactobacillus and Gardnerella .Partnering, mating, and fathering play importantroles in MRH as well . The 2006 Van Anders andWatson study showed that men with lower

testosterone levels were more likely to be partneredthan those with higher testosterone levels .Difference. The book focuses on the beginning ofan idea and its growth to a social epidemic .The 2008 Cannon, et al . study demonstrated theimportant role of fathers in the father-mother-childtriad . An emerging body of literature is showing thatfathers play a role in the outcomes of reproduction,particularly by influencing their children well beyondthe sperm donor relationship . The components ofeffective fathering include psychological functioning,relationship conflict, and parenting style . The 2009Schacht, et al . study demonstrated a slight associationbetween fathering behaviors and child adjustment,such as problem drinking and depressive symptoms .In addition to CDC hosting its first MRH meeting, other“tipping points” leading up to this effort include the2003 meeting by the U .S . Agency for InternationalDevelopment on MRH and gender equity; the longhistory of the HHS Office of Population Affairs, Officeof Family Planning, in increasing male involvementin family planning by offering services to menthrough Title X clinics; and recent conferences byother groups to advance the evidence base of MRHactivities and formulate strategies to better educatemen about infertility . Two additional influencesinclude the 1965 book by Norman Ryder and CharlesWestoff, Reproduction in the United States, a hallmarkof available data at the time on men’s and women’sreproductive health; Robert Hatcher’s ContraceptiveTechnology, today a world-renowned resource oncontraception now entering its 20th edition .Understanding of masturbation is important tounderstanding men’s sexual health . A numberof studies have been conducted on the role ofmasturbation in men’s sexual and reproductive health .This research includes the 2008 Dimitropoulou, etal . study on the role of masturbation in prostatecancer risk in men 50 years of age; the 2009 Ammanstudy on the role of masturbation in semen quality;and the 2008 Santilla, et al . study on the negativeassociation between masturbation and relationshipsatisfaction . However, these studies are not particularlyrigorous and additional research is needed .Masturbation is considered to be the definingcharacteristic of male sexual behavior rather thanpenile-vaginal intercourse, oral sex, or other partneredsexual behaviors . The 2010 Herbenick, et al . studyanalyzed masturbation over the past month among2,879 men and 2,842 women . The study showedthat masturbation was substantially more commonin recent sexual behavior among men than womenover the lifespan of 14–15 to 70 years of age .Overall, men’s reproductive health must encompassand focus on the entire body beyond the penis .CDC’s Past and Current Men’sReproductive Health ActivitiesLee Warner, PhD, MPHAssociate Director for ScienceCenters for Disease Control and PreventionNational Center for Chronic Disease Preventionand Health PromotionDivision of Reproductive HealthDr . Warner highlighted CDC’s past and current MRHactivities . The field of male reproductive health wasdescribed as currently being at a “tipping point,”a term borrowed from Malcolm Gladwell’s book,The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a BigAdvancing Men’s Reproductive HealthA 1994 statement by the World Health Organization(WHO) serves as the best available definition of MRHbecause this language is not gender-specific . WHOdefined health as—A state of complete physical, mental,and social well-being and not merely the absence ofdisease or infirmity . Reproductive health addresses thereproductive processes, functions, and systems at all stagesof life. Reproductive health, therefore, implies that peopleare able to have a responsible, satisfying, and safe sexlife and that they have the capability to reproduce andthe freedom to decide if, when, and how often to do so.It is hoped that adoption of the WHO’s 1994 statementas the definition of MRH will be embraced by thediverse group of participants attending the MRHmeeting, including federal agencies, academia,professional societies, industry, and private practitionerswho share a common goal and investment inMRH . This includes urologists, reproductive healthspecialists, endocrinologists, STD and family planningpractitioners, and obstetricians/gynecologists .CDC has made a number of notable accomplishmentssince its establishment in 1946 as the Public HealthService Malaria Program to its present role as theCenters for Disease Control and Prevention . In itscurrent organizational structure, CDC’s three majoroffices are the Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, andLaboratory Services; the Office of NoncommunicableDiseases, Injury, and Environmental Health; and theOffice of Infectious Diseases . National Centers inthese three offices are responsible for conductingactivities relative to CDC’s public health mission .While CDC does not have a either a formal or fundedMRH program, several National Centers and Institutesconduct activities in this area . The National Center forSummary of Scientific essions

Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion(NCCDPHP), Division of Reproductive Health (DRH)analyzes reproductive health surveys that have collecteddata on vasectomies, infertility, in vitro fertilizationcycles in the United States, and sexual and reproductivehealth of persons 10–24 years of age . Other NCCDPHPdivisions have conducted research on the relationshipbetween smoking and male infertility; rates ofprostate and testicular cancer; and healthy behaviors,adverse risk behaviors and the use of preventivescreening in adolescents, adults, and communities .The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) hasadministered the National Survey of Family Growthsince 1973 and began including men of reproductiveage in the survey in 2002 . NCHS also administersother surveys including the National Health andNutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) andthe National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) .The National Institute for Occupational Safetyand Health (NIOSH) has conducted occupationalstudies to determine the impact of chemical andphysical exposures on male and female reproductivehealth . One of NIOSH’s most prominent studiesfocused on the association between bicycle seattype and the rate of sexual dysfunction amongpublic safety workers who regularly rode bicycles .Results from this study led to recommendationsencouraging the use of “no-nose” bicycle saddles .The National Center for Environmental Health (NCEH)and the Agency for Toxic Substance and DiseaseRegistry (ATSDR) have conducted studies on the impactof environmental exposures on male and femalereproductive health . This research has included therelationship between diethylstilbestrol and testiculardeformities in male offspring, male reproductivehealth risks to Vietnam veterans from Agent Orange,and risks to Gulf War veterans from other exposures .The National Center on Birth Defects andDevelopmental Disabilities (NCBDDD) has conductedstudies on sexual issues and reproductive healthneeds among persons with disabilities, such as theuse of contraception and decision making, sexualdysfunction, and the relationship between variousexposures and birth defects . NCBDDD’s 1984 studydocumented the risk of Vietnam veterans fatheringinfants with birth defects . Another NCBDDD studywith 1994–2004 data found an association betweenpaternal age and risk for major congenital anomalies .The National Center for Injury Prevention andControl (NHIPIC) has conducted a number ofstudies to document that men are survivors ofcrime and violence in addition to women . TheNational Center for Immunization and Respiratory12Diseases has developed and released guidanceon vaccine-preventable diseases (i .e ., hepatitis B,human papillomavirus or HPV, and mumps) thataffect men of reproductive age . The National Centerfor Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases isresponsible for examining all new and emerginghealth threats including those that may affect MRH .The National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TBPrevention (NCHHSTP) has a long history of conductingprimary and secondary prevention initiatives from bothbehavioral and biomedical perspectives . These activitiesinclude creating the National STD Treatment Guidelines,producing the HIV/STD Partner Services Guidelines, andtaking a lead role in developing the National HIV/ AIDSStrategy . MRH data collected by all of these NationalPrevention Centers and Institutes are available tothe public on the CDC Web site (www .cdc .gov) .CDC’s Sexual Health ActivityJohn M. Douglas, Jr., MDChief Medical OfficerCenters for Disease Control and PreventionNational Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD,and TB PreventionDr . Douglas described CDC’s new public healthapproach to advancing sexual health in the UnitedStates . The 2001 Surgeon General’s Call to Action toPromote Sexual Health and Responsible Sexual Behaviorfocused on the need to promote sexual health andresponsible sexual behavior across the lifespan andstimulate respectful, thoughtful, and mature discussionsabout sexuality in communities and homes .The Surgeon General’s Call to Action further noted thatsexual health is an essential component of overallindividual health, has a major impact on the overallhealth of communities, and should be includedin a national dialogue at all levels as a criticalfactor in improving population health .CDC believes it is a priority to strengthen the focus onsexual health endorsed by the 2001 Surgeon General’sCall to Action because of recent trends in the UnitedStates . STDs, HIV, and other sexual health problems,along with their associated costs, have a highpopulation burden . Of 19 million STD infections thatoccur each year, 50% are among young persons15–24 years of age . Data show that 1 in 4 women14–19 years of age is infected with at least one STD .Estimates show that 1 .1 million Americans are livingwith HIV at this time and 55,000 new infectionsoccur each year . Of all pregnancies in the UnitedStates, 50% are unintended . HIV and other STDs

are associated with major health disparities, with rates8 to 20 times higher among African Americans thanwhites and 40 to 50 times higher among men whohave sex with men than other men . STDs, includingHIV, are estimated to cost 15 .9 billion per year .Teen pregnancy rates in the United States began toincrease in 2006 after a 15-year decline . In addition,data from the United Nations Demographic Yearbookindicate that in 2006, the U .S . teen pregnancy rate of41 .9/1,000 females was substantially higher in thanany other developed country . At the other end ofthe lifespan, AARP released its third national surveyof Sex, Romance, and Relationships in midlife andamong older adults in April 2010 . The survey showed astrong interest in sexual health among older adults .To advance sexual health in the United States, CDCconvened a Sexual Health Consultation on April 28–29,2010 . The purpose of the meeting was for participantsto articulate the rationale, vision, and priority actionsfor a public health approach to advance sexualhealth in the United States . CDC staff and externalconsultants worked together as a Sexual HealthSteering Committee to develop a sexual health greenpaper, “A Public Health Approach for Advancing SexualHealth in the United States: Rationale and Options forImplementation.” The green paper is intended as aliving document to stimulate discussion and will serveas the basis for the publication of a formal CDC White(policy) Paper in the future . (Editor’s note: A summaryof this document was released in August 2011 and isnow available online at www .cdc .gov/sexualhealth) .CDC identified three major advantages of a sexualhealt

Men’s Reproductive Health in the United States: Current Status and Future Directions.” The meeting was originally planned to help CDC staf and our Federal colleagues gain insights into the emerging areas of public health activit