Transcription

Food for thought:Mental health and nutrition briefing1P O L I CY B R I E F I N G2017

Key messageDietary interventions may besignificant to a number of the mentalhealth challenges society is facing,but we need to know more. There isa lack of investment in research andthe translation of knowledge intostraightforward guidance about foodproduction and consumption. Nutritionis more than the sum of individualchoices and behaviours. Public policyis vital to ensuring that healthy food isunderstood, available and affordable forall.What we eat and drink affects how wefeel, think and behave. With the recentAdult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey(APMS)i finding that one in six peoplehave experienced a common mentalproblem such as anxiety or depressionin the last week, the need for effectiveapproaches to understanding andimproving mental health has never beengreater.1 This briefing focuses on hownutrition can be effectively integratedinto public health strategies to protectand improve mental health andemotional wellbeing. It discusses whatwe know about the relationship betweennutrition and mental health, the risk andpositive factors within our diets andproposes an agenda for action.The role of diet in the nation’s mentalhealth has yet to be fully understood andembraced. The messages about nutritioncan appear to be changeable andcontradictory, and shifts in policy andpractice have been slow to materialise.A general lack of awareness of theevidence base, as well as scepticismabout its quality, have limited progressin embracing the role of nutrition inpeople’s mental health. However, this isbeginning to change.One of the most obvious yet underrecognised factors in the developmentof mental health is nutrition. Just like theheart, stomach and liver, the brain is anorgan that requires different amounts ofcomplex carbohydrates, essential fattyacids, amino acids, vitamins, mineralsand water to remain healthy. Anintegrated approach that equally reflectsthe interplay of biological factors, as wellas broader psychological, emotional andsocial conceptions of mental health, isvital in order to reduce the prevalenceand the distress caused by mental healthproblems: diet is a cornerstone of thisintegrated approach.It is necessary for individuals,practitioners and policy makers to makesense of the relationship between mentalhealth and diet so we can make informedchoices, not only about promoting andmaintaining good mental health but alsoincreasing awareness of the potentialfor poor nutrition to be a factor instimulating or maintaining poor mentalhealth.i. The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (2016) is a survey of mental health and wellbeing across theUK. It covers diagnosed mental health problems, substance dependence and suicidal behaviour, andtheir causes and consequences.2

Key terms:Diet: Usually refers to the kinds of food that a person habitually eats. InWestern culture ‘diet’ is also often applied to the lifestyle changes used tolose weight. Although applied to the changes most often used to resolvea problem associated with being overweight or health issues, this maybe more in line with the Latin origins of the word taken from the Greek‘diaita’, meaning a ‘way of life’.2Balanced diet: Refers to eating a wide variety of foods in the rightproportions and consuming the right amount of food and drink to achieveand maintain a healthy body weight (NHS Choices).3Nutrition: Refers to the quality of the food we eat (for example, whetherfood is processed or fresh), the kind of food we eat (for example, whetherfoods are vitamin and mineral rich; or how many calories they contain),how we chose to eat (quantity, timing, motivation for eating differenttypes of food) and how the food has been produced (for example, has itbeen treated with pesticides?).3

Nutrition and mental health: why is therelationship important?Integrated mind-body approaches tosupporting mental health have increasedin popularity in recent years, withstudies supporting the links betweenexercise,4 sleep,5 mindfulness,6 andacupuncture7 and mental health. Thereis a growing body of evidence indicatingthat nutrition may play an importantrole in the prevention, developmentand management of diagnosed mentalhealth problems including depression,anxiety, schizophrenia, Attention DeficitHyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) anddementia.non-communicable diseases such asType 2 diabetes, Coronary Heart Diseaseand some cancers. Less understoodis the contribution made by diet tomental health. This is due in part to thecomplexity of the relationship, and theneed to take into account the effectsof other factors. Research has alreadyprovided evidence that there is a strongrelationship between physical healthand mental health, such as the increasedincidence of depression in those withheart disease, establishing that there isan indirect link.8 The evidence is nowbuilding about the direct associationbetween what people eat and how theyfeel.It is common knowledge in the UK thatthere is a well-established link betweendiet and physical health, especially for4

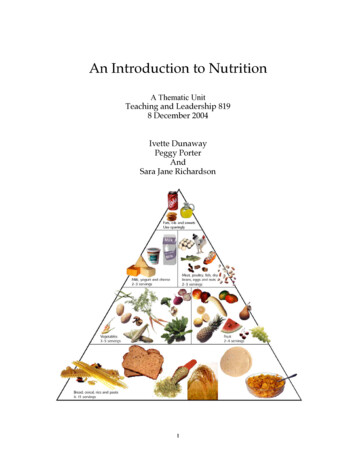

Dietary Recommendations:The UK government’s dietary recommendations are put together with theguidance and advice from the Committee on Medical Aspects of Foodand Nutrition Policy (COMA) and its successor since 2000, the ScientificAdvisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN).9Eatwell, the government’s food consumption guidelines, provide the mostup to date overview of which food groups should be consumed on a dailybasis, and in which proportions, to achieve a healthy diet.10 It outlines theproportions of the main food groups that form a healthy, balanced diet: Eat at least 5 portions of a variety of fruit and vegetables every day Base meals on potatoes, bread, rice, pasta or other starchycarbohydrates; choosing wholegrain versions where possible Have some dairy or dairy alternatives (such as soya drinks); choosinglower fat and lower sugar options Eat some beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other proteins (including 2portions of fish every week, one of which should be oily) Choose unsaturated oils and spreads and eat in small amounts Drink 6-8 cups/glasses of fluid a day. If consuming foods and drinkshigh in fat, salt or sugar have these less often and in small amounts5

Protective factors for mental healthFeeding the brain with a diet thatprovides adequate amounts of complexcarbohydrates, essential fats, aminoacids, vitamins, minerals and watercan support healthy neurotransmitteractivity. It can protect the brain fromthe effects of oxidants, which have beenshown negatively to impact mood andmental health. Evidence of nutrition’sprotective qualities can be identifiedacross the life course.11smoking, the study found that of thoseexamined, the behavioural risk factormost consistently associated with bothlow and high mental wellbeing in acrossboth sexes was the individual’s fruit andvegetable consumption.15Vitamins, minerals and acidsVitamins and minerals (calledmicronutrients) perform a number ofessential functions, including assistingessential fatty acids to be incorporatedinto the brain and helping amino acidsconvert into neurotransmitters.ii Theyplay a crucial part in protecting mentalhealth due to their role in the conversionof carbohydrates into glucose, fatty acidsinto healthy brain cells, and amino acidsinto neurotransmitters.From a young age, good nutritionalintake has been linked to academicsuccess, with a number of studiesreporting that providing children withbreakfast improves their academicperformance.12 A number of publishedstudies have shown that hungry childrenbehave worse in school, with reportsthat fighting and absence are lower andattention increases when nutritiousmeals are provided.13Deficiencies in micronutrients havebeen implicated in a number of mentalhealth problems. Unequal intakesofomega-3 and omega-6 fats in the diet,for example, are implicated in a numberof mental health problems, includingdepression, and concentration andmemory problems; and studies haveshown that increased consumption ofthese fatty acids can be helpful in thecontrol of bipolar depressive symptoms.16Reports suggest that these fatty acidshave an association with better mentalhealth even after adjustment for otherfactors (income, age, other eatingpatterns), and a reduced risk of cognitiveimpairment in middle age.17As we age, the protective effect that diethas on the brain is evidenced in researchfindings that a diet high in essential fattyacids and low in saturated fats slows theprogression of memory loss and othercognitive problems.14Fruit and vegetablesA study conducted by Stranges et al.(2014), in England, found that vegetableconsumption was associated with highlevels of mental wellbeing. Along withii. They are termed ’essential’ as they cannot be made within the body, so must be derived directly fromthe diet.6

Table 3: Table of essential vitamins and minerals, the effects of various and where tofind them18NutrientEffect of deficiencyFood sourcesVitamin B1Poor concentration andattentionWholegrainsVegetablesVitamin B3DepressionWholegrainsVegetablesVitamin B5Poor memoryStressWholegrainsVegetablesVitamin B6IrritabilityPoor memoryStressDepressionWholegrainsBananasVitamin B12ConfusionPoor memoryPsychosisMeatFishDairy productsEggsVitamin CDepressionVegetablesFresh fruitFolic acidAnxietyDepressionPsychosisGreen leafy reen heat germBrewer’s yeastLiverFishGarlicSunflower seedsBrazil nutsWholegrainsZincConfusionBlank mindDepressionLoss of appetiteLack of motivationOystersNutsSeedsFish7

Risk factors for mental healthBroadly speaking, there are two groupsof foods that can have a negative effecton brain function. One group trick thebrain into releasing neurotransmittersthat we may be lacking, thereby creatinga temporary alteration in mood (forexample caffeine and chocolate);and one group damages the brain bypreventing the necessary conversionof other foods into nutrients the brainrequires (for example, saturated fat suchas butter, lard and palm oil).higher intake of foods with saturatedfat, refined carbohydrates andprocessed food products) are linked topoorer mental health in children andadolescents.19 Beyer and Payne (2016)found that people with a diagnosis ofbipolar disorder tend to have a poorerquality diet, which is high in sugar, fatand carbohydrates.20A study looking at the changing dietsof people living in the Artic and SubArtic regions found that levels ofdepression were rising at the same timethat traditional diets, which were highin Essential Fatty Acids, were beingabandoned and replaced by moreprocessed foods.21Consuming processed foodsand additivesA systematic review conducted byO’Neil et al. (2014) showed thatunhelpful dietary patterns (includingSugar consumption:The World Health Organization’s guidance on free sugars intakerecommends: a reduced intake of free sugars throughout the life course (strongrecommendation ). in both adults and children, reducing the intake of free sugars to lessthan 10% of total energy intake2 (strong recommendation).iii further reductions of the intake of free sugars to below 5% of totalenergy intake (conditional recommendation).iv, 22iii. Strong recommendations indicate that “the desirable effects of adherence to the recommendationoutweigh the undesirable consequences”. WHO handbook for guideline development, 2nd edition.(2014). Geneva: World Health Organization.iv. Conditional recommendations are made when there is less certainty “about the balance betweenthe benefits and harms or disadvantages of implementing a recommendation”. WHO handbook forguideline development, 2nd edition. (2014). Geneva: World Health Organization.8

The role of food in preventing mentalhealth problemsAs well as the links between diet andpositive mental health, including healthybrain development, there is emergingevidence that good quality nutritionmay play a role in contributing to theprevention of mental health problemsand in the management and recoveryfrom these when and if they do occur.coronary heart disease, some cancers,osteoporosis and dental diseases.24PovertyA multitude of psychological, social,cultural and economic factors createthe context for our choices about whatand how we eat. Poverty is a key riskfactor for both mental health and diet.25The complex and cumulative impactsof poverty and mental health problemson quality of nutrition are affected by:income, knowledge and skills, availabilityand quality of food as well as time, healthand convenience.There are a range of inequalities thatcan contribute to the developmentof mental health problems, includingthe heightened risk associated withpoor physical mental health and socioeconomic factors such as poverty. Boththese inequality factors have also beenshown to have a complex relationshipwith poor nutrition as describedbelow. The emerging science lookingat syndemics (synergistic epidemics)considers ‘co-morbid health conditionsthat are exacerbated by their socio,political, environmental and politicalmilieu’.23 This provides a conceptualframework which may help us tounderstand the ‘synergy’ between the‘epidemics’ of obesity and mental healthproblems and the actions that we needto take to shift the conditions that arecurrently allowing these to becomesignificant public health challenges.The quality of an individual’s,household’s and community’s diethas a socioeconomic gradient. Whilehigher-quality diets are associatedwith greater affluence, energy-densediets that are nutrient-poor are morefrequently consumed by persons oflower socioeconomic status and of morelimited economic means. 26Poor physical healthPoor physical health is a risk factor fordeveloping mental health problems.Changes in food production techniques,such as processing, the use of additivesand industrialised farming have allbeen directly attributed to seriousphysical health problems including9

It has been argued that psychosocialfactors in childhood obesity are moreimportant than functional limitations,and that children who are obese mightbe better helped by providing socialsupport, rather than to focus on thechild’s diet and exercise levels.31 Thistopic is discussed in more detail in 2011National Obesity Observatory ‘Obesityand mental health report’.32Household income and socio-economicstatus influence decisions aboutwhat people eat, with this becomingan increasingly important factor ashousehold income decreases. Peopleliving in households in receipt ofstatutory benefits consume fewerportions of fruit and vegetables thanthose in non-benefit households.27Numbers of those admitted to hospitalwith malnutrition rose to more than5,400 in 2012, at the same time as thenumber of people fed by food bankswent to 347,000 in in the same year. 28The impact of nutritional challenge onmental health status in these groupsneeds to be investigated.AlcoholAlcohol and mental health have acomplicated relationship. Mental healthproblems can not only result fromdrinking too much alcohol, they canalso contribute to people drinking toomuch. In short, alcohol has a depressanteffect and can lead to rapid deteriorationin mood. Alcohol interferes with sleeppatterns which can lead to reducedenergy levels. Alcohol depresses thecentral nervous system, and this canmake our moods fluctuate. It can be usedby some to help ‘numb’ emotions, to helppeople avoid confronting difficult issues.Alcohol is also associated with disruptivesleep patterns, dietary changes andnutritional deficiencies. The impact ofnutritional changes on mental healthresulting from alcohol intake has yet tobe fully understood however studieshave shown the importance of vitamin Bin preventing alcohol related dementia(Korsakoff’s Syndrome).Co-morbidityObesityThe relationship between obesity andmental health problems is complex.Results from a 2010 systematic reviewof longitudinal studies found twoway associations between depressionand obesity, finding that people whowere obese had a 55% increased riskof developing depression over time,whereas people experiencing depressionhad a 58% increased risk of becomingobese’.29Although obesity can be the resultof poor diet, there are a number ofdemographic variables that could affectthe direction and/or strength of theassociation with mental health includingseverity of obesity, socioeconomic statusand level of education, gender, age andethnicity.30This is discussed in more detail in ouronline A-Z on our website.10

The role of diet in relation to specificmental health problemsThere is growing evidence that dietplays an important contributory role ina number of diagnosed mental healthproblems. This section presents theevidence for the links between diet anddepression, schizophrenia, dementia andAttention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder(ADHD).Similar conclusions have been drawnfrom studies looking at the associationof depression with low levels of zinc andvitamins B1, B2 and C, as well as studieslooking at how standard treatmentshave been supplemented with micronutrients resulting in greater reduction insymptoms in people with a diagnosis ofdepression and bipolar disorder.36DepressionSchizophreniaDepression is the most common mentalhealth problem in the UK. TalkingTherapies and Self-Managementapproaches such as Mindfulness havebeen building in popularity as selfchosen alternatives or complementsto anti-depressant medication.Interventions that focus on the mind/body link such as exercise eitherprescribed or as a self-help technique33and emerging areas like acupuncture34are also gathering momentum. Diethas emerged as another therapeuticapproach seen directly in the work ofAdult Mental Health Dietitians, who workwith people who experience mentalhealth problems to improve knowledgeand awareness of nutrition.Although a complex area somestudies have illustrated that diet canbe associated with the onset anddevelopment of schizophrenia. TheDutch Famine Study and 1960s Chinesefamine, found that severe famineexposure in early pregnancy lead to atwo-fold increase in the diagnosis ofschizophrenia requiring hospitalisation inboth male and female children.37, 38Studies have found that people withschizophrenia have lower levels ofpolyunsaturated fatty acids in theirbodies than the general population,and that antioxidant enzymes arelower in the brains of people withschizophrenia. Further research is nowbeing undertaken in this area to identifyspecific mechanisms through whichdiet can work alongside other treatmentoptions to prevent or alleviated thesymptoms of schizophrenia.39A number of large studies have linkedthe intake of certain nutrients withreported prevalence of different types ofdepression. A recent study exploring thecorrelation between low intakes of fishby country and high levels of depressionamong its citizens found that those withlow intakes of folate, or folic acid, weresignificantly more likely to be diagnosedwith depression than those with higherintakes.35DementiaMany studies have shown a positiveassociation between a low intake of fats,and high intake of vitamins and mineralsin the prevention of certain forms of11

dementia. One study looking at thetotal fat intake of 11 countries founda correlation between higher levels offat consumption and higher levels ofdementia in the over 65s age group.40A long-term population based studyfound that high levels of vitamin C and Ewere linked to a lower risk of dementia,particularly among smokers, with similarfindings in other studies focused ondifferent population groups.41with the highest rates of those screeningpositive for ADHD recorded in thoseaged 16–24 (14.6%).43Clinical research has reported thebenefits of essential fatty acids andminerals such as iron. Deficiencies iniron, magnesium and zinc have beenfound in children with symptoms ofADHD, and studies have consistentlyshown significant improvements withsupplementation when comparedwith placebo, either alongsidenormal medication or as stand-alonetreatments.44, 45, 46Attention Deficit HyperactivityDisorder (ADHD)ADHD occurs in approximately 1 in 10(9.7%) of adults in the UK.42 Rates ofADHD appear to decrease with age,Eating disordersAn individual’s relationship with food can develop into a negativecoping mechanism to handle emotional distress. Rather than behavioursmanifesting because of the food itself, the relationship is based more uponthe notion of controlling one’s weight in response to a range of possibletriggers, for example, neurochemical changes, genetics, lack of confidenceor self-esteem, perfectionist personality trait, problems such as bullying,or difficulties with school work.Food can play a big part in an individual’s eating disorder, but the realitiesof eating disorders are often much more broad and complex as thepre-occupation with food is only the outward sign of a desperate innerturmoil.47This is discussed in more detail in our online A-Z on our website.12

DiscussionThere are emerging but in some cases clearlinks between diet, access to good qualitynutrition and mental health status. Just asthe association between diet and physicalhealth took some time to understand andembrace, there has been a similar patternfor nutrition and mental health. Clinicalstudies point to the importance of diet asone part of the jigsaw in the preventionof poor mental health and mental healthproblems and the promotion of positivemental health and brain development.However, there remain gaps in theevidence base that need to be addressedif the relationship between nutritionand mental health are to be effectivelyreflected in policy.many mental health problems and sometreatments. For example, strategies thatfocus on enhancing an individual’s selfworth and development of self-efficacy canhelp overweight patients to improve boththeir emotional wellbeing and sustain weightloss.Nutrition has moved up the agenda forpolicy makers, although attention has beenfocussed mainly on addressing obesity,as has been seen in England, Wales andScotland. This said, the Framework forPreventing and Addressing Overweightand Obesity49 in Northern Irelandencouragingly recognises nutrition, obesityand mental health as interlinking, presentingrecommendations that accurately reflectthe evidence base. The emerging frameworkof syndemics (synergistic epidemics) mayoffer a starting point to understanding thecomplex relationship between contextualfactors operating across society and thegrowing public health challenges andpersonal distress caused by increasing ratesof obesity and mental health problems.There are two main issues with thecurrent evidence base. First, that itremains challenging to establish a causal(that is a direct) relationship ratherthan simply a correlation; and second,there is a lack of studies examining thecontribution of combined nutritionalsupplements with individual nutrientsusually examined in isolation. Further, dueto the methodological variation in studies,comparison of results is challenging. Thefocus on single nutrients means that theeffects of whole-of-diet interventions arenot well evidenced.There is an urgent need for policy-makers,practitioners, industry, people whoexperience mental health problems and thewider public to recognise and act on therole that nutrition plays in mental health. Toachieve parity between mental and physicalhealth, it is vital that the public are informedabout the type of diet that will promotetheir mental health in the same way food ispromoted for physical health reasons. Ofequal importance will be understandingthe mediating role that mental health playsin our lifestyle choices, including our diet.However wider impact can be achievedby national and local policy, well beyondindividual actions.Although good nutritional intake alonemay not significantly reduce the overallprevalence rates of mental healthproblems, diet plays a contributingrole and is a modifiable risk factor thatcan be targeted by low cost, low riskinterventions.48 Good diet has the addedbenefit of counteracting the adversephysical health effects associated with13

Policy recommendations1. Promote community level schemes toprovide access to affordable nutritiousfood, particularly in communitiesat higher risk of developing mentalhealth problems.6. The Department for Environment,Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA)needs to ensure that agriculturalpolicy reflects the evidence base onhealthy and mentally healthy foodproduction. Specifically, supportshould be increased for the growthand availability of affordable organicproduce, fruit and vegetables, othermicro-nutrient rich food and foralternative sources for omega-3 fats,given the global shortages of oily fish.2. Improve nutritional literacy(embedded as part of a nationalmental health literacy programme)by ensuring evidence basedprogrammes/initiatives are publiclyavailable. There should be a particularfocus on education in schools withpractical food skills, including cookingand growing, reintroduced as a partof the national curriculum for allstudents.7. National NHS bodies need to ensuremental health multidisciplinary teamshave routine access to dieticians toprevent people with mental healthproblems developing physical healthconditions and to support them tomanage the impact of medications onphysical health.3. Extend schemes such as HealthyStart50 across the country toensure all children, throughouttheir development, have access toappropriate levels of micronutrients.8. National Health Education andPublic Health bodies need to includenutrition within professional trainingcurricula for health, social care andeducational professionals to helpthem identify where poor nutritionmay be a factor in mental ill health,and to help people understand how toimprove their mental health throughmaking dietary changes, providingguidance on eating well at low cost.4. GPs should be encouraged andsupported to test people fornutritional deficiencies if they suspectthat their mental health problemscould be linked to poor diet, and toprescribe supplements if there is adeficiency.5. Introduce regulation to supportthe promotion of healthy food tochildren, and to protect them from themarketing of unhealthy foods.9. Prioritise and invest in a mentalhealth and nutrition research agendathrough public health research bodiesand programmes, to improve thequality of and access to evidence onwhat works.14

Additional Mental HealthFoundation resourcesFeeding Minds: The impact of food on mental download/feeding-mindsA-Z PagesDiet and mental t-and-mental-healthAlcohol and mental ohol-and-mental-healthAnorexia orexia-nervosaAttention deficit hyperactivity disorder ention-deficit-hyperactivitydisorder-adhdBipolar ipolar-disorderBulimia alth.org.uk/a-to-z/d/depressionMealtimes and mental entalhealth.org.uk/a-to-z/s/schizophrenia15

References11. Can antioxidant foods forstall aging? UnitedStates Department of Agriculture Food andNutrition Research Briefs, April 1999. http:www.ars.usda.gov1. Stansfeld, S., Clark, C., Bebbington, P., King,M., Jenkins, R., & Hinchliffe, S. (2016). Chapter2: Common mental disorders. In S. McManus, P.Bebbington, R. Jenkins, & T. Brugha (Eds.), Mentalhealth and wellbeing in England: Adult PsychiatricMorbidity Survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital.12. Meyers AF, Sampson AE, Weitzman M,Rogers BL, Kayne H: School Breakfast Programand school performance. Am J Dis Child 1989;143(10):1234-92. English Oxford Living Dictionaries. (2017).Diet. Retrieved from: 3. Murphy JM, Pagano ME, Nachmani J, SperlingP, Kane S, Kleinman RE: The relationship ofschool breakfast to psychosocial and academicfunctioning: cross-sectional and longitudinalobservations in an inner-city school sample. ArchPediatr Adolesc Med 1998; 152(9):899-9073. NHS Choices. (2017). Eating a balanced diet.Retrieved from: ating.aspx4. Richardson AJ, Montgomery P: The OxfordDurham study: a randomized, controlled trialof dietary supplementation with fatty acidsin children with developmental coordinationdisorder. Pediatrics 2005; 115(5):1360-614. Gómez-Pinilla, F. (2008). Brain foods: theeffects of nutrients on brain function. Nat RevNeurosci. 2008 Jul; 9(7): 568–578.5. Harvard Medical School. (2009) Sleepand Mental Health. Harvard: Harvard HealthPublications. Retrieved from: http://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter article/Sleep-andmental-health15. Stranges, S., Samaraweera, P.C., Taggart, F.,Kandala, N.B., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2014). Majorhealth-related behaviours and mental well-beingin the general population: The Health Survey forEngland. BMJ Open, 4(9), e0058786. Kerr, C. et al. (2013). Mindfulness starts withthe body: somatosensory attention and topdown modulation of cortical alpha rhythms inmindfulness meditation. Frontiers in HumanNeuroscience, 7.16. Beyer, J., & Payne, M.E. (2016). Nutrition andBipolar Depression. Psychiatric Clinics of NorthAmerica, 39(1), 75–86.17. Kalmijn S, van Boxtel MP, Ocke M, VerschurenWM, Kromhout D, Launer LJ: Dietary intakeof fatty acids and fi sh in relation to cognitiveperformance at middle age. Neurology 2004;62(2):275-807. Burgess JR, Stevens L, Zhang W, Peck L: Longchain polyunsaturated fatty acids in children withattention-defi cit hyperactivity disorder. Am JClin Nutr 2000; 71(1 Suppl):327S-30S18. Holford P: Optimum Nutrition for the Mind.London: Piatkus. 20038. Naylor, C et al. (2012). L

The World Health Organization’s guidance on free sugars intake recommends: a reduced intake of free sugars throughout the life course (strong recommendation ). in both adults and children, reducing the intake of free sugars to less tha