Transcription

Beyond Trainingand the “Skills Gap”Research and Recommendations forRacially Equitable Communicationsin Workforce Development2019

BEYOND TRAINING AND THE “SKILLS GAP ”:Research and Recommendations for Racially Equitable Communications in Workforce DevelopmentExecutive SummaryPurposeAS PART OF A THREE-YEAR RACE FORWARD PROJECT on racial equity in workforcedevelopment, Beyond Training and the “Skills Gap” – Research and Recommendations forRacially Equitable Communications in Workforce Development provides a broad picture forthe field’s leaders and professionals of how the workers they serve – particularly workers ofcolor – are framed in the media coverage of jobs in two expanding, higher wage industries –technology and health care. The report also provides the workforce development field withpractical tips for racially equitable communications to broaden the collective responsibility foremployment and other economic outcomes in our communities.Research Question: To what extent are workers – particularly workers of color – framed inindividualist vs. systemic ways in workforce development-related coverage of technology andhealth care jobs in mainstream media?Practice Question: How can the field of workforce development better incorporate, and evencenter racial equity in communications?The technology and healthcare sectors are at a crossroads: they can ignore or insufficientlyaddress the realities of systemic racism and thereby reinforce the inequities of the status quo;or they can consciously choose to explicitly address race and become the drivers of equitableand inclusive change. The following recommendations provide a pathway for workforcedevelopment strategies in these sectors to move from being passively part of the problem toactively part of the solution – racially equitable and inclusive workforces prepared to meet thecritical needs and challenges of our ever-changing and complex society.Defining Individualist vs. Systemic FramesINDIVIDUALIST FRAMINGIndividualist framing of jobs in the growing fields of technology and healthcare, as well asin other spheres of our economy, centers the responsibility of employment outcomes—fromhiring, to retention, to career progress, to earnings, etc.—almost entirely on individualinitiative and work ethic. It includes such terms and phrases as “unskilled,” “training,” “softskills,” and “skills gap,” among other descriptions of individual deficiencies when it tell storiesof individuals. If the employer is explicitly incorporated into the story, it is typically to lamentthe impact of the skills gap and lack of available workers on the company’s growth prospects.RACE FORWARD 20192

BEYOND TRAINING AND THE “SKILLS GAP ”:Research and Recommendations for Racially Equitable Communications in Workforce DevelopmentIf the employer is included as part of the solution to employment challenges, it does notextend beyond providing charity to support more job training or otherwise improving thesoft-skill deficiencies of workers.While many workforce development agency professionals argue that the hard- and soft-skilldeficiencies of their clients are indeed real, even if that is the case, Race Forward argues thatracially equitable outcomes will not come through a singular focus on prospective employeesalone.SYSTEMIC FRAMINGSystemic framing, by contrast, uses language and stories that substantively cover the lack ofresources underlying the skills gap and the disparities we see in employment outcomes. Theseresources include education, transportation, social network access, and others that are oftenplace-based. Ideally, systemic framing addresses the role of employer discrimination andinequitable policies and practices, whether carried out intentionally or not.At its best, systemic framing discusses the root causes and compounding effects ofdisparities across systems, and suggests solutions in the broadest sense of state and societalresponsibility and shared prosperity. Systemic frames expose implicit biases and challengenotions that racism, sexism, and classism no longer erect meaningful and deeply troublingbarriers to success. Systemic frames lift up human dignity and a historically informed senseof fairness.If our goal is to have a shared responsibility and commitment to equitable employmentoutcomes, systemic framing is essential. And for the purposes of broadly contrastingthe individualist (dominant) frames from the systemic (“alternative”) frames, this studyconsidered any article touching on these themes to be “systemic,” regardless of whetheror not race or racism was explicitly mentioned. However, our analysis does make thesedistinctions within the category of systemic framing in order to explore the extent to whichthe mainstream media and workforce development agencies seem to be more comfortablediscussing the systemic barriers and solutions around factors other than race.And to be clear, we argue that to advance a vision of racial justice, systemic framing mustincorporate an explicit racial lens. While important discussions can and should be had aboutmany social, economic, and other factors, race and racism are too often left out of commondiscourse. We believe that workforce development leaders and communications teams canand should do more to use an explicit racial equity lens far more often to counteract themainstream framing of the workers they serve.Key Findings1. Individualist framing dominates [Note: larger FONT for bold]. Individualist framing– which often centers a) the “skills gap” between workers and vacant employmentRACE FORWARD 20193

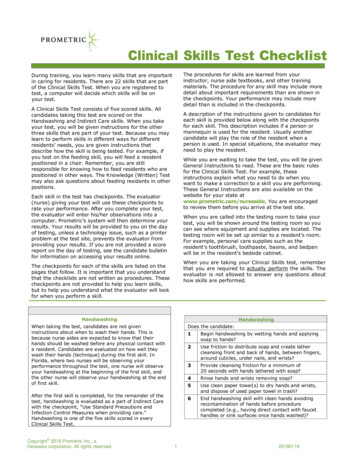

BEYOND TRAINING AND THE “SKILLS GAP ”:Research and Recommendations for Racially Equitable Communications in Workforce Developmentposition, and/or b) the need for job training – dominates the mainstream mediacoverage of jobs in technology and healthcare, with more than three-quarters(76.5%) of all the coverage in our analysis featuring individualist framing (see Figure1). Moreover, individualist framing is too often unchallenged, considering 50.2%of the coverage exclusively featured individualist framing, compared to only 7.8%containing exclusively systemic frames (See Figure 1).2. Even when present, systemic framing typically must compete with individualistframing. Overall, only about one third (34.1%) of the workforce development-relatedcoverage of technology and healthcare jobs in mainstream media contained systemicframing (see Figure 1). And while mainstream media coverage tends to includemore systemic framing when worker demographics are identified (e.g., in the 54.8%of coverage when the income level, and/or gender of workers, etc. are explicitlymentioned), individualist framing is nevertheless simultaneously ever present. Forexample, while 55.6% of the articles with raced workers (typically workers of color)contained some significant systemic framing, only two out of 36 articles (5.6%)exclusively did (see Figure 3). Almost nine out of ten articles (88.9%) with workers ofcolor included individualist framing.3. Infrequent attention to race. When worker demographics of any type are included inmainstream coverage of tech and healthcare jobs, workers of color are featured lessoften than “non-raced” workers, which includes low-income workers, women, theformerly incarcerated, etc.4. Insufficient attention to race in systemic framing. When systemic frames are present,the media devotes more attention to non-raced workers – (i.e., the race of the workersis unspecified in the text) than to raced workers.MethodologyRACE FORWARD CONDUCTED MEDIA CONTENT ANALYSIS of 200 mainstreamnewspaper and wire articles from Jan 2016 to October 2017 of 1) technology or healthcarejobs, or 2) a sample of workforce development organizations that Race Forward had been incontact with in mid- to late 2017 about centering racial equity in their work. As a result, thelevels of systemic framing reported in this study are more likely to be higher than just generalcoverage of the workforce in other industries beyond tech and healthcare, or of workforcedevelopment agencies more broadly speaking (i.e., those who were not already inclined topursue some racial equity training and/or coaching).Race Forward researchers compiled the data set both through broad terms (e.g., “workforcedevelopment and tech and diversity”) and through specific agencies (e.g., “[agency name] andjobs and health OR tech”). And we coded articles for individualist and/or systemic framing,and for the type of workers discussed: people of color, gendered (typically women workers),low-income, formerly incarcerated, etc.RACE FORWARD 20194

BEYOND TRAINING AND THE “SKILLS GAP ”:Research and Recommendations for Racially Equitable Communications in Workforce DevelopmentCommunications RecommendationsCURRENT CONCEPTUALIZATIONS AND COMMUNICATIONS related to workforcedevelopment in both the technology and healthcare sectors insufficiently address theexistence, realities, and impacts of systemic racism. Without a more complete analysis of race,these sectors not only reflect, but replicate patterns of racial inequity and exclusion. Becauseboth sectors play such pivotal roles in our society and daily lives, the accessibility, composition,and competencies of their respective workforces matter. These sectors are at a crossroads:they can ignore or insufficiently address the realities of systemic racism and thereby reinforcethe inequities of the status quo; or they can consciously choose to explicitly address raceand become the drivers of equitable and inclusive change. The following recommendationsprovide a pathway for workforce development strategies in these sectors to move from beingpassively part of the problem to actively part of the solution – racially equitable and inclusiveworkforces prepared to meet the critical needs and challenges of our ever-changing andcomplex society. Address race early and often. A race-centered conversation needs to becomenormalized and habitual. Addressing race early and often means making it part ofthe discussion at the beginning and throughout the process of functions such asprogram development and review, strategic planning, communications strategydevelopment, grant-writing, etc. Address race inclusively and intersectionally. Race is often, but not the only, salientdynamic contributing to social inequities. You can address racism explicitly, notexclusively, because other factors also matter. It’s also important to address raceintersectionally because the combination of being a person of color and also beinga woman, or also having a disability, can have compounding impacts that must beunderstood. Address race proactively and preventatively. When racism is addressed, it is oftenfrom a reactive framework—for example, once discrimination has occurred or biasand barriers are uncovered. The goal of racially equitable systems change is proactiveand preventative in order to get ahead of the curve so that racial inequities anddiscrimination are not produced in the first place. Provide training to leadership and all staff in racial equity competencies. Racialequity competency—which is related to but distinct from cultural competency—involves understanding systemic racism and racial equity and includes skills such asusing racial equity impact assessment tools, authentically engaging stakeholders indecision-making, and using strategies to remove bias and barriers. Conduct an organization-wide assessment of content using a racial equity lens.Racial bias or a lack of a racial analysis can show up in all kinds of organizationalcontent—social media posts, promotional and marketing materials, program andservice descriptions, media releases, strategic plans, policy positions, etc. It canbe helpful to review these documents to find and remove bias and to move fromindividual blame to a systemic frame. Creating and using a style guide tailored to theparticular programs and audiences of the workforce development organization canRACE FORWARD 20195

BEYOND TRAINING AND THE “SKILLS GAP ”:Research and Recommendations for Racially Equitable Communications in Workforce Development be a way to ensure more clarity and consistency in future content development andcommunications.Replace phrases and words that reinforce dominant frames on race and replacethem with racial justice frames. “Skills gap” is one example of a term that has thetendency to reinforce individual accounting of racial disparities in employment.Instead, use words and phrases that focus on systemic barriers like “employmentdiscrimination” or “policies and practices” or “lack of institutional support.” Involvingmore people of color in the conceptualization and formulation of organizationalcontent and communications, can help the products be more representative, andideally speaking in the language of lived experience.Counteract institutional implicit bias by using racial equity decision-makingtools. The use of Racial Equity Tools is becoming a common practice in large systemssuch as government agencies. These tools provide a series of steps and questionprompts that can be used for policy-making, planning, budgeting, hiring, programdevelopment, service delivery, etc.Hire more people of color in content development and communications roles.People who have experienced racism firsthand can best understand its impacts andrealities. Conversely, people who are disconnected from the realities of racism orfrom communities of color are more prone to developing well-intentioned, but oftenunconsciously biased, content. Omission—who is left out of consideration, whichissues and needs are ignored, and which systemic factors are not considered—is oftenmore of a problem than commission.Become clear on the needs and benefits of addressing and advancing racialequity in the specific and overall sectors of healthcare and technology. Forexample, in the field of public health, many government agencies have been at theleading edge of embracing a systems-view of healthcare for decades, with explicitconsiderations of the social determinants of health. This informs health strategiesthat can significantly improve the quality of people’s lives, and even save lives.Applying a similar systems analysis framework to workforce development in thehealthcare sector can also inform strategies for advancing equity and inclusion inthe sector itself. Building an inclusive and equitable technology workforce is key tobuilding an inclusive and equitable technology, which in turn plays a critical rolein building an open and democratic society dependent on the free and inclusiveexchange of information and ideas. In your communications, you should includelanguage that speaks to the vision of a skilled, diverse workforce.ConclusionWITH CONSCIOUS ANALYSIS, COMMITMENT AND ACTION, the field of workforcedevelopment can play a critical role in expanding collective understanding for the rootcauses of racially inequitable outcomes in our economy, as well as in broadening supportfor collective responsibility of racially employment outcomes. Too often, mainstream mediadepictions of jobs and workforce development in high-earning fields, such as healthcare andRACE FORWARD 20196

BEYOND TRAINING AND THE “SKILLS GAP ”:Research and Recommendations for Racially Equitable Communications in Workforce Developmenttechnology, center on individual-level explanations for failure and success. That means toomany journalists utilize the terms of individualist framing – such as “skills gap” and “jobstraining” – with insufficient attention to systemic perspectives that can build support fornot just increased education resources, but transportation infrastructure, child care support,implicit bias training for workforce development trainers and employers, social capital growth,recruitment and hiring practices, retention programs, and so on.Race Forward urges leaders in the field of workforce development to in fact lead with racialequity explicitly—but not (necessarily) exclusively—in both their internal and externalcommunications and practices. To do otherwise allows past and present racial inequities inour employment and related systems to persist with the unspoken or explicit assumption thatindividual-level training and “personal responsibility” are the only factors needed for success,and that our current, broad racial inequities are the result of broadscale personal failures. Thefield of workforce development can and must speak more explicitly about racially equitablesolutions and for its commitment to racial equity for the workers it serves.RACE FORWARD 20197

BEYOND TRAINING AND THE “SKILLS GAP ”:Research and Recommendations for Racially Equitable Communications in Workforce DevelopmentTable of Contents09Introduction16A Brief Note on Methodology17Findings from Mainstream Media Analysis26Communications Recommendationsfor the Field of Workforce DevelopmentBeyond Training and the “Skills Gap” wasmade possible by the generous support of theW.K. Kellogg Foundation.Principal InvestigatorDominique Apollon, PhD (Vice President of Research)Additional ResearchersTara Conley, EdD (former Research Director)Julia Sebastian (Manager, Research and Impact Planning & Evaluation)Primary AuthorsDominique ApollonTerry Keleher (Director of Strategic Innovations)Additional WritingDennis Chin (Director of Strategic Initiatives)Copy EditorKathryn DugganRACE FORWARD 20198

BEYOND TRAINING AND THE “SKILLS GAP ”:Research and Recommendations for Racially Equitable Communications in Workforce DevelopmentIntroductionTHE FIELDS OF TECHNOLOGY AND HEALTHCARE are two of the nation’s fastestgrowing U.S. industries, where workers are typically paid higher wages and are offeredmore employment benefits than their counterparts in other large industries. The industries’growth is so fast, in fact, that much of the national media conversation on these jobs centerson the inability of employers to find enough qualified workers to fill their needs. But thecorresponding emphasis on the “skills gap” and the need for workforce development trainingof individual workers is only part of the story that needs to be told. For while the fast-growingtechnology and healthcare fields may indeed be the waves of the future in terms of highearning workforce growth, these industries are more likely to exacerbate the racial disparitiesof our past and present if more is not done to build collective responsibility and commitmentfor equitable economic outcomes. To ensure a racially equitable future, we need greaterawareness of the language we use to discuss jobs, workers, and the stories we tell.There are many institutions and sectors that can play a positive role in growing technology,healthcare, and other industries more equitably—including business, investors, and educators;as well as government, philanthropy, and labor organizations. As part of Race Forward’smulti-year W.K Kellogg Foundation-funded racial equity project [www.raceforward.org/workforceequity] in the field of workforce development, Beyond Training and the “Skills Gap”:Research and Recommendations for Racially Equitable Communications in Workforce Development wasdesigned to provide a broad picture to agency leaders, communications staff, and others inthe workforce development field of how rarely the workers they serve—particularly workersof color—are framed in systemic ways in mainstream media. That is to ask, to what extent arejobs in these industries framed in ways that broaden the scope of responsibility for the raciallyinequitable outcomes we see? In what ways can we expand the collective commitment to anequitable future?The research findings included in this report should be of interest and use to anyone seekingto advocate for a fair and racially equitable economy. This includes those who work in media,government, business, and labor advocacy or education who appreciate the need to challengethe “meritocratic” assumptions and dismissiveness—whether conscious or unconscious—thatare too often the default in our nation for matters of the economy. Accordingly, as a racialjustice advocacy organization, we provide recommendations for communicating aboutracial equity in these and other fields, and for language and stories that expand the scope ofresponsibility for economic outcomes in our society.RACE FORWARD 20199

BEYOND TRAINING AND THE “SKILLS GAP ”:Research and Recommendations for Racially Equitable Communications in Workforce DevelopmentRace Forward seeks to normalize explicit discussions about systemic racism and thecorresponding institutional and structural solutions. While the challenges experienced bylow-income workers, women in the workplace, and people of color are often overlapping,they aren’t the same. And some workers or prospective workers—for example, low-incomewomen of color—may simultaneously experience the compounding challenges of all three.When social justice advocates and other economic stakeholders aren’t explicit about race andsystemic racism, our default, sometimes unspoken understanding of the underrepresentationof Black and Brown workers in these industries—in hiring, retention, promotions, andleadership—is that these negative outcomes are the workers’ own individual fault.In 2016 and 2017, our researchers analyzed over 200 items from mainstream media coverage ofjobs in the health and technology sectors, as well as coverage of many workforce developmentagencies that service them. The purpose of this research was to identify how and to whatextent the news coverage reinforces or challenges the dominant frames (e.g., personalresponsibility, individualism, and unquestioned meritocracy) that situate a “skills gap” asthe central or sole challenge and the “training” of individual workers as the central or solesolution.From the perspective of racial justice advocacy, individualist framing is problematic, amongother reasons, because it largely if not entirely absolves institutions and systems from theirshare of responsibility for racial and ethnic employment outcomes. Individualist framingtaps into a mythology of the self-made person and the “American dream” that if a personworks hard enough, they will succeed in life socioeconomically. It can also convey the oftenunspoken but arguably more important corollaries that a) if one has not succeeded, it is due toindividual mistakes and/or lack of effort; b) if one has succeeded, it was largely or entirely dueto initiative and hard-work; and access to more resources, opportunities, fair treatment, andother privileges play little to no role in this inequality.We also tracked the extent to which systemic framing was incorporated into the mainstreammedia coverage. For example, we tracked whether or not the coverage of jobs and workforcedevelopment agencies in the technology and healthcare industries included any mentionor deeper discussion about the underlying causes of the disparate outcomes that exist inthese fields. For example, systemic framing can help paint a portrait of a more collectiveresponsibility for outcomes. This perspective incorporates the key roles that are, or that couldbe, played, for example, by employers, educational institutions, government agencies, andrelated collaborations and partnerships.Distinguishing Systemic Framingfrom Individualist FramingIndividualist framing of jobs in the growing fields of technology and healthcare, as well asin other spheres of our economy, centers the responsibility of employment outcomes—fromhiring, to retention, to career progress, to earnings, etc.—almost entirely on individualRACE FORWARD 201910

BEYOND TRAINING AND THE “SKILLS GAP ”:Research and Recommendations for Racially Equitable Communications in Workforce Developmentinitiative and work ethic. This is also referred to as “dominant” framing in this report becausethe language and explicit or implicit stories of this frame are the most commonly expressedand shared in our inequitable society.Dominant individualist framing of jobs in the fields of healthcare and tech includes suchterms and phrases as “unskilled,” “training,” and “skills gap,” among other descriptionsof individual deficiencies when it tell stories of individuals. If the employer is explicitlyincorporated into the story, it is typically to lament the impact of the skills gap and lack ofavailable workers on the company’s growth prospects. If the employer is included as partof the solution to employment challenges, it does not extend beyond providing charity tosupport more job training or otherwise improving the soft-skill deficiencies of workers.While many workforce development agency professionals argue that the hard- and soft-skilldeficiencies of their clients are indeed real, even if that is the case, Race Forward argues thatracially equitable outcomes will not come through a singular focus on prospective employeesalone.With half a million technology jobs currently open and nearly twomillion similar new jobs expected to be created in the next decade, anew JPMorgan Chase & Co. report released today reveals that therapidly growing and quickly evolving tech training field faces uniqueobstacles for developing the skilled and diverse workforce required tomeet a growing need in our economy.“New JPMorgan Chase Report Reveals Uncertainty Over How Well Tech TrainingPrograms Are Meeting Employers’ Needs,” Business Wire. (8 March 2016.)Systemic framing, by contrast, uses language and stories that substantively cover the lackof resources underlying the skills gap and the disparities we see in employment outcomes.These resources include education, transportation, social network access, and others that areoften place-based. Ideally, systemic framing addresses the role of employer discrimination andinequitable practices, whether carried out intentionally or not.At its best, systemic framing discusses the root causes and compounding effects ofdisparities across systems, and suggests solutions in the broadest sense of state and societalresponsibility and shared prosperity. Systemic frames expose implicit biases and challengenotions that racism, sexism, classism no longer erect meaningful and deeply troublingbarriers to success. Systemic frames lift up human dignity and a historically informed senseof fairness.If our goal is to have a shared responsibility and commitment to equitable employmentoutcomes, systemic framing is essential.RACE FORWARD 201911

BEYOND TRAINING AND THE “SKILLS GAP ”:Research and Recommendations for Racially Equitable Communications in Workforce DevelopmentSystemic Framing—Race Explicit or Not?Race Forward challenges systemic racism, and consistently advocates for explicit (thoughnot necessarily exclusive) discussions of racial equity, inclusion and justice, as the reader willlater note in the recommendations section that concludes this report. But in the interest ofconceptual clarity, it is important to note that a label of “systemic” framing in this study, doesnot necessarily mean an article included explicit discussions of workers of color, race, orracism.1Systemic framing sometimes emphasizes different types of independent or overlappingthemes, including race, class/income, gender, and additional identities and orientations.Each of these systemic frames featured language or content that moved beyond theindividual worker or workers’ responsibility for employment outcomes. Those might bethe systemic barriers and challenges faced by workers struggling with poverty, or thegender discrimination faced by women, or the employment barriers faced by the formerlyincarcerated or otherwise “disadvantaged” workers.For the purposes of broadly contrasting the individualist (dominant) frames from the systemic(“alternative”) frames, this study considered any article touching on these themes to be“systemic,” regardless of whether or not race or racism was explicitly mentioned. However,our analysis does make these distinctions within the category of systemic framing in order toexplore the extent to which the mainstream media and workforce development agencies seemto be more comfortable discussing the systemic barriers and solutions around factors otherthan race.And to be clear, we argue that to advance a vision of racial justice, systemic framing mustincorporate an explicitly racial lens. While important discussions can and should be had aboutmany social, economic, and other factors, race and racism are too often left out of commondiscourse. We believe that workforce development leaders and communications teams canand should do more to use an explicit racial equity lens far more often to counteract themainstream framing of the workers they serve.1Previous Race Forward research documented in the 2014 report Moving the Race ConversationForward – Part I: How the Media Covers Racism, and Other Barriers to Productive RacialDiscourse defined “systemically aware” media content as that which “mentions or highlightspolicies and/or practices that lead to racial disparities; describes the root causes of disparitiesincluding the history and compounding effects of institutions; and/or describes or challengesthe aforementioned.” In order to draw a greater contrast between individualist framing and otherframes, “systemically” framed content is not as narrowly defined in this study. Race Forward’sgoals remain the same today, as we continue to advocate for explicit, though not exclusive, racialframing and discussion of systems and systemic racism and solutions in our society.RACE FORWARD 201912

BEYOND TRAINING AND THE “SKILLS GAP ”:Research and Recommendations for Racially Equitable Communications in Workforce DevelopmentExamples of Different Types of Systemic Framing:Statements and concepts that we consider key to theparticular type of systemic framing identified.SYSTEMIC FRAMING BASED ON CLASS AND INCOME2017 may be our region’s most ambitious year yet in our collective work toimprove our community and people’s lives. . . .The Child Poverty Collab

initiative and work ethic. It includes such terms and phrases as “unskilled,” “training,” “soft skills,” and “skills gap,” among other descriptions of individual deficiencies when it tell stories of individuals. If the employer is explicit