Transcription

KÜRŞAT CESURTurkeyOpening Many Locks with aMaster Key: Six EFL GamesPlayed with a Set of CardsBeing a lucky child, I played lots of games, as my parents wereprimary-school teachers, and playing games is a natural part ofgrowing up and learning. More recently, I took the opportunity tocreate new games while teaching a course called “Teaching English toYoung Learners” to preservice teachers of English. Among these games,there are more than 20 that can be played using only one set of cards,including those described online at TenTen 4 Kids (2018a); teachers andstudents can make these cards by using the example template in theAppendix. In this article, I describe six of these games that I have eitheradapted or created.Many games for children are played to teachor review one specific notion or function;for example, the “Directions Game” offerspractice in giving instructions (Lewis andBedson 1999, 91), and “Body Writing” helpslearners review shapes, letters, and numbers(Phillips 1993, 97). The card games in thisarticle can be used with vocabulary relatedto a variety of topics. What makes the gamessignificant is that they are all played usingonly one set of cards that can be reproducedto create four pictures for each vocabularyitem. After you have prepared the worksheet(see the Appendix) for your game cards,and by using Creative Commons–licensedimages from websites such as Flickr orGoogle Images, you can play these gameswith that set of cards.There is no “best” in English languageteaching, but often there is “better.” Here,I have included six of the most successfulcard games for teaching English. Three of the1ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM2 01 9games are rousers, which are movement games;the other three are settlers, in which studentslisten to their friends carefully and play thegames in groups at their seats (Lewis andBedson 1999, 7).CARD GAMES FOR YOUNG LEARNERSGames are essential tools for having fun,and “children have an enormous capacity forfinding and making fun” (Halliwell 1992, 6).Learning a language is not “the keymotivational factor” for them (Lewis andBedson 1999, 5).Young children typicallydo not come to the classroom to learn alanguage; rather, they want to play a game orhave fun. The card games described here notonly encourage children to learn a language,but also add variation to lessons.Why to PlayTeachers can use the card games to helpstudents practice recently learned ng-forum

(Lorenzutti 2016) or to introduce newwords. The games provided here may seemto have little focus on the language, as atmost students either say one word at a time(of an object, usually) or hear one wordspoken by the teacher. However, the gamescan be made more linguistically complexif teachers ask students to form sentences,ask questions, or write dialogues for furtherpractice using the vocabulary. Additionally,students learn from the situations describedby the teacher while he or she is explainingthe rules of the games or while they areplaying. That is to say, students may “needand want to communicate in a meaningfuland intense way in that they need to uselanguage to have a turn at playing, to pointout the rules, to challenge another player”(Korkmaz 2012, 307).When to PlayTeachers can integrate the games into theirsyllabus. If they have a flexible program,they can either supplement the core materialor replace activities they dislike (Lewis andBedson 1999). Teachers can fit the gamesinto a 45-minute period to take a break frommore-serious studies or use them to givestudents a reward for completing a particularlydifficult task. They can also be used as warm-upactivities or as follow-ups to a lesson.With Whom to Playreaders to overlook activitieswhich might be just what they need.(Lewis and Bedson 1999, 11)Instead of including language levels, I haveprovided classification of suggested age groupsfor each game in Table 1.We cannot expect that all language classestake place with ten to 16 students. Manyclassrooms are crowded. We need to haverealistic expectations of ourselves and thelearners; however, this does not mean that weshould reject the idea of playing games in ourclasses. On the contrary, “being realistic shouldmean taking realities into account in such a waythat good things can still happen” (Halliwell1992, 19). For teachers with classes of morethan 25 students, I have the following tips: “Divide a class up into smaller, moremanageable groups which can play gamesmore effectively” by splitting “players intoteams” or setting up “game stations” in theclassroom (Lewis and Bedson 1999, 12). Organize tournaments between groups.If you play the game with a limitednumber of students, the rest of thestudents do not even follow along.However, in tournaments, while twogroups are playing, the others followwith interest because the result affectsall groups, especially the groups that willplay the following game against either thewinner or the loser. In this way, everyonein the class is involved in the process.The card games described here can be playedwith young learners. Language levels of thestudents playing these games can range frompre-A1 to A2 levels of English. However, thegames can also work with other sets of wordsat more difficult levels (TenTen 4 Kids 2018b). Rotate roles in games where one group canLike Lewis and Bedson (1999), I decided thatact as facilitator before rotating to becomeclassifying the games according to languageplayers, with another group then becominglevel would not be realistic:facilitator. However, this might not workin games where the teacher is neededLanguage level does not reflect the realto decide whether an answer is correct,challenge of the games, which you willpronunciation is clear, and so on.find in the nature of the activity itselfrather than in the language component. Involve a large class in making and cuttingIn addition, since most games havegame cards, such as those in the Appendix.numerous variations with differentFor example, a game with 20 cards forlanguage input aimed at varying agefour players in a class of 40 students wouldgroups, giving a language level could leadrequire 200 cards—and that would be m2019ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM2

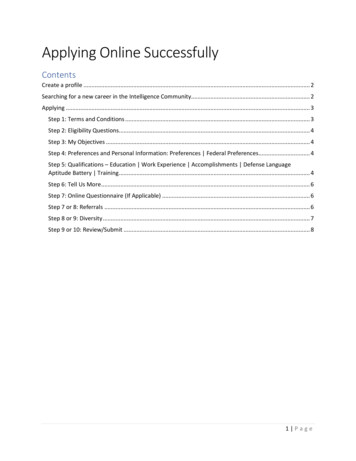

just one set of vocabulary items. Of course,you can save the cards and laminate themfor future use, but many teachers in thissituation would have trouble producingthis many cards. However, students cancreate cards either by themselves or withthe help of their parents. This has anadditional benefit because “if you can getparents involved from the start they willbe supportive of your and the children’sefforts” (Phillips, Burwood, and Dunford1999, 13). If each student prepares thegame cards of the single worksheet, therewill be four cards for each item when theclass plays the games in groups of four.SIX CARD GAMES FOR YOUNG LEARNERSTable 1 summarizes six games that can be playedwith sets of cards. It is only a rough guide,and you should “use your own knowledge ofyour children to judge whether the activityis suitable for your class” (Phillips 1993, 13).You can adapt the games and use variations todevelop different skills with different numbersof students in different age groups.At the end of each game description is a linkto a short video that shows how the game isplayed. We made the videos with prospectiveteachers of English rather than with younglearners; this was due to the difficulties ofobtaining permission of all parents to havetheir children appear in the videos.1.3PUT INTO ORDERclass, “I need two lines,” and students form twolines at the back of the classroom. Put one setof eight cards face down on a desk next to oneline of students, and another set of eight cardsface down on a desk next to the second line ofstudents. Mix up both sets of cards. At the frontof the room, arrange a row of eight cards facedown on a desk in front of one line of students,and another row of eight cards face down ona desk in front of the second line of students.You may also arrange the cards face down on awhiteboard or blackboard tray. This means 32cards are needed to play the game.The class can play the game at different levelsof difficulty. They start by memorizing threecards and finish by memorizing all of thecards. For this game to be played effectively,you can give the following instructions:I need one student from each group.The firststudent in each line will come to the board,turn over the first three cards in the row, andmemorize the pictures.Then, you will putthe cards face down again. After that, returnto your seat at the back of the class, find thecorrect three cards from the set of cards onyour group’s desk, and put them into order.The student who finishes ordering the cardsfirst and says, “Ready” will be asked to saythe words in order. If the order is correct,that person’s team will get a point.The firststudent will go to the end of the line, andI will mix up the rows of cards at the frontof the room.The game will continue withthe next student in each line, who will haveto memorize the first four pictures.Thenthe next student in each line will have tomemorize the first five pictures, and so on.I created this game after watching the popularTV program Survivor. The competitors runfrom the back to the front of the room andmemorize ordered vocabulary items; theythen run to the back of the room and arrangethe items in the order they have memorized.They earn points if the items are orderedcorrectly. I realized it could be fun to playsuch a game with young learners.For each student, check to see whether thecards are ordered correctly; if you want, youcan also check for correct pronunciation. If theorder is correct, that team gets a point. If not,the point goes to the other team. The groupwith more points at the end is the winner.In this game, you need four identical setsof eight cards. Each card depicts a differentvocabulary item (you may increase or decreasethe number of cards at your discretion). Tell theA variation of this game is having studentsmake up a story with the words that arememorized correctly. This gives studentsthe opportunity to practice using the targetENGLISH TEACHING FORUM2 01 9americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

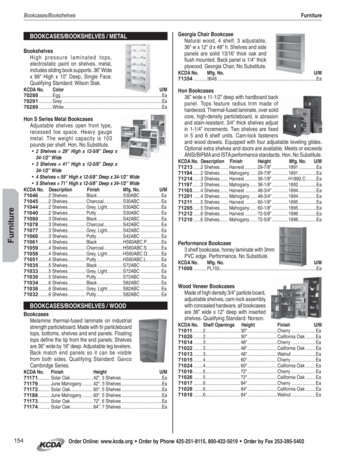

language, no matter how funny and silly thestories they make up are.My students loved this game because theywere familiar with it due to a popular TVprogram. Creative teachers of English asa foreign language (EFL) can watch gameson TV and consider how they can adaptand play them in their own classes. A videodemonstration of this game can be found athttps://youtu.be/PMU7WgJ5lFk.2 . PASS THE RIVERAfter playing the game “What’s That Card?”(Lewis and Bedson 1999, 105) with myName ofGameDescriptionSkill/LanguageAreasNumber ofPlayersAgeGroup1. Put intoOrderA game adapted from the TVprogram Survivor. Students try tomemorize the pictures on the boardand return to their seat at the back ofthe class, find the correct cards, andput them into order. If everything iscorrect, the team gets a point!Cooperation;writing orspeaking(building 0–122. Pass theRiverStudents try to guess what the cardis on the stones of an imaginaryriver. The group that guesses all thecards and reaches the treasure firstis the winner.Concentration;memorization;social 123. Stick ItYou say a word, and the studentsfind the card showing the picture ofthat word and stick it on the board.Whoever is first gets a 16*6–88–104. HappyFamiliesStudents aim to collect families(four of the same card). The winneris the player with the most laryBestplayed ingroups of 48–1010–125. Repetition Students have to repeat the wordsas many times as they can. The gamegoes on until one of them makes amistake in calling out the names ofthe vocabulary items in order. Theone who makes a mistake dropsout of the game. The last playerremaining is the winner.Concentration;memorization;social skills;vocabulary;pronunciationBestplayed ingroups of 48–1010–126. BombVocabulary;grammar;pronunciationCan beplayed inpairs or ingroups of 46–88–1010–12The game is also known as “OldMaid” or “Odd One Out.” Eachplayer removes all the pairs fromhis or her hand and pronounces thewords. The game goes on in thisway until all cards have been pairedexcept one—the Bomb, whichcannot be paired—and the playerwho has that card loses the game.Table 1. Six card games for young learners (*More students can play the game when you have atournament in the forum2019ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM4

students, I adapted it to make it morecompetitive.You need two cards for eachvocabulary item children have just learned.Divide the class into two groups and havethem line up. Draw two imaginary riverson the floor and a treasure chest at the endof each river. Put the two sets of cards facedown on the floor in a mixed order. Studentsimagine that these are the stones of the riverthat they need to step forward on in order toreach the treasure. As in the game What’s ThatCard?, you say:Come to the stones of the river. Tryto guess what the card is and turn thecard up to check whether your guess iscorrect. If it is correct, you can go onand guess the next card. If your guess iswrong, all cards will be turned down,and another student from your teamwill come to the river and startguessing the cards from the beginning.The group that guesses all the cardsand reaches the treasure first is thewinner.5To play, you need to divide the class into twogroups. Two cards for each vocabulary itemare needed. Put the two sets of cards face upon a table and say:When I give the command, one studentfrom each group will come to the table.Each of you has the same number ofcards in front of you. I will say a word—for example, pineapple, and you will tryto find the card showing the picture ofthat word. Whoever finds the correctcard and sticks it on the board first getsa point. At the end of the game, thegroup with more points is the winner.Games with simple, clear, and logicalinstructions work best with young learners.The best activity in the world can be a wasteof time if students do not understand it.If you have problems in the games as I didwhile playing Flyswatter, you can adapt thegames considering your students’ needs andinterests.Children have to follow the game carefully toturn over all the cards correctly and to reachthe treasure. They need to play the gamecollaboratively to finish it successfully. As aresult, the game can also develop students’social skills. A video demonstration of thisgame can be found at https://youtu.be/k1oK32u9bTw.The game can also be turned into a readingactivity. Give a simple text to both studentsand ask them to find cards showing picturesof words that appear in the text. Whoeverfinds the correct cards and sticks them onthe board in the correct order first will bethe winner. A video demonstration of thisgame can be found at https://youtu.be/ud3q 4lIrFA.3 . STICK IT4 . HAPPY FAMILIESThis game was adapted from a populargame called “Flyswatter,” available atvarious English as a second languagewebsites. In Flyswatter, each student holdsone flyswatter and swats the correct wordon the board when the teacher says theword. I had problems while playing thisgame in my classes, as students attemptedto slap each other, or they complained thatthe word I said was nearer to the memberof the opposing team. The adapted game,“Stick It,” has the same fun elements butremoves the problems I have noticedwith Flyswatter.I have played this game with my studentsseveral times in the way that Nixon andTomlinson (2003) and Phillips (1993)suggest, where students ask each otherif they have a certain card. However,I noticed that some children do notrespond correctly to their friends’ questions.Though they have the card in their hands,they say they do not have it, as a way to getcards themselves later on. Therefore,I adapted the game and decided to playit with the cards face up on the table.All students should see which cards theirfriends have.ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM2 01 9americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

The game requires four each of eight cards,or 32 cards in total. Shuffle the cards and dealfour cards face up to four students who standat a table. Each student tries to collect cardsfrom other players by asking, “Have you got?” or “Do you have ?” Ifthe answer is “Yes,” the other players have togive up the card that was asked for. Each timestudents give cards to the questioner, they willget new cards from the backup pile; everystudent should have four cards before a newquestion is asked. If the answer is “No,” it isthe next player’s turn to ask. If players havea matching pair, they can put these cards faceup in front of their game-playing cards. Theaim is to collect families (a set of four of thesame card). Once a player has a set of four,he or she places it face down on the table andgets a point. The game is over when there areno game-playing cards left. The winner is theplayer with the most sets.This game is useful in that all formsof a sentence (simple, imperative, andinterrogative) can be practiced. A videodemonstration of this game can be found athttps://youtu.be/RRhlsyvjJRI.5 . REPETITIONThis game is similar to the one thatShaptoshvili (2002, 35) called the “MemoryGame.” There is also a game with the samename in which children try to find pairsof matching cards. That game is also called“Pick Up Twos” (Phillips 1993, 111) and“Pelmanism” (Lewis and Bedson 1999, 120).I have named this game “Repetition,” as astudent has to repeat as many target wordsas he or she can. In this game, you need todeal an equal number of cards to fourstudents and say:The first student will start the game byputting a card on the table and sayingwhat is on the card—for example,“Pineapple.” The second student willput down a card on top of the first cardand call out the names of both cards,starting from the first one—for example,“Pineapple and watermelon.” The thirdstudent will put another card on top ofthe two cards, then call out the first twocards and the new one—for example,“Pineapple, watermelon, and coconut.”The game goes on until one of you makesa mistake in calling out the names of thecards in order. The one who makes amistake must drop out of the game. Thelast player remaining is the winner.A video demonstration of this game can befound at https://youtu.be/zGP 80B6CZY.6 . BOMBThere are many card games played by adults,but few of them have been adapted to teachEnglish to young learners. This game is similarto the popular card game “Old Maid” or “OddOne Out.” My students named it “Bomb.” Toplay the game, you need four cards for eachvocabulary item, but you must take out onecard from the deck; that card is the Bomb.Shuffle the cards and deal them, one at a timeto each player, until all the cards have beenhanded out. Then say:Players take turns removing all the pairsfrom their hands, pronouncing the word,and putting those pairs on the table. Ifyou have three-of-a-kind, you can removeonly two of those three cards. One of youthen will offer your hand to the player onyour left, who will draw one card from it.This player will discard any pair that mayhave been formed by the drawn card. Thatplayer then will offer his or her own handto the player on the left. The game goeson in this way until all cards have beenpaired except one—the Bomb—whichcannot be paired. The player who has thatcard loses the game.If you play the game with pictures of actionverbs, you can practice grammar as well.While students are putting down the pairs,instruct them to form a statement—“Heis playing the piano”—or a question—“What instrument is he playing?” A videodemonstration of this game can be found te.gov/english-teaching-forum2019ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM6

Some of these card games are easy tounderstand and have clear and simpleinstructions.Your students can understandwhat to do after you give the instructionsfor the game, especially if you make useof demonstration, mime and gestures, andexamples. However, some games, such as“Happy Families” and “Put into Order,”have difficult rules to explain. According toSowell (2017, 10), “instruction-giving has adirect effect on learning; a lesson or activitybecomes chaotic and fails when students donot understand what they are supposed to do.”In my experience, once students learn howto play the games, you will not need to givethe same instructions again, as they will knowwhat to do when you just tell them the nameof the game. Sowell addresses the importantissue of using the mother tongue to giveinstructions:There might be instances when the use ofthe L1 for instruction-giving is justifiedfor the sake of efficiency and clarity,but there is a danger of overuse and thepossibility that students and teachers willbecome accustomed to the comfort ofinstructions in the L1. (Sowell 2017, 11)While it is useful to clarify the rules ofthe games using students’ mother tongue,especially for young learners at the beginninglevel, it can be counterproductive when thestudents get used to it and expect it.CONCLUSIONThe games presented here are a small sampleof the many games that can be played with aset of cards.You can even let your studentscreate their own games; according toHalliwell (1992, 6), “no matter how well weexplain an activity, there is often someonein the class who produces a version of theirown! Sometimes it is better than the teacher’soriginal idea.”Here, I have presented games with easy-toprepare materials, hoping that other Englishlanguage teachers will try them in their ownclasses. Do not hesitate to adapt or change7ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM2 01 9them. Moreover, try to integrate the gamesthat your students enjoy most into yoursyllabus, for “if an activity is enjoyable, it willbe memorable; the language involved will‘stick’, and the children will have a sense ofachievement which will develop motivationfor further learning” (Phillips 1993, 6). Whatlanguage teachers see as enjoyable may notbe true for young learners; therefore, thelearners’ needs and interests should be thefirst thing to consider. Finally, I hope you cancreate your own card games and contribute tothe list provided in this article.REFERENCESHalliwell, S. 1992. Teaching English in the primaryclassroom. Harlow, UK: Longman.Korkmaz, Ş. 2012. Games. In Teaching English to younglearners: An activity-based guide for prospective teachers,ed. E. Gürsoy and A. Arıkan, 305–326. Ankara,Turkey: Eğiten Kitap.Lewis, G., and G. Bedson. 1999. Games for children.Oxford: Oxford University Press.Lorenzutti, N. 2016. Vocabulary games: More than justwordplay. English Teaching Forum 54 (4): 2–13.Nixon, C., and M. Tomlinson. 2003. Primaryvocabulary box: Word games and activities for youngerlearners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Phillips, D., S. Burwood, and H. Dunford. 1999. Projectswith young learners. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Phillips, S. 1993. Young learners. Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press.Shaptoshvili, S. 2002. Vocabulary practice games.English Teaching Forum 40 (2): 34–37.Sowell, J. 2017. Good instruction-giving in the secondlanguage classroom. English Teaching Forum 55 (3):10–19.TenTen 4 Kids. “Card Games for TeachingEnglish to Young Learners.” YouTube videos.June 3, 2018a. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list PL2MMHmzRhac6njiQAAwH4w9WLXjTfZuHj———. “Put Into Order Game for Young Adults.”YouTube video, 09:00. June 5, 2018b. https://youtu.be/UUUBVFM9910Kürşat Cesur is Dr. Lecturer at the English LanguageTeaching Department of Canakkale Onsekiz MartUniversity, where he started working as an instructorof English in 2004 and has been offering the course“Teaching English to Young Learners” to preserviceteachers of English since rum

APPENDIXSample Cards for Teaching Vocabulary to Young -forum2019ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM8

Turkey Opening Many Locks with a Master Key: Six EFL Games Played with a Set of Cards B eing a lucky child, I played lots of games, as my parents were primary-school teachers, and playing games is a natural part of growing up and learning. More recently, I took the opportunity to crea