Transcription

Judicial BranchProcurementCourts Generally Met ProcurementRequirements, but Some Need toImprove Their Payment PracticesJanuary 2021REPORT 2020‑301

CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR621 Capitol Mall, Suite 1200 Sacramento CA 95814916.445.0255 TTY 916.445.0033For complaints of state employee misconduct,contact us through the Whistleblower Hotline:1.800.952.5665Don’t want to miss any of our reports? Subscribe to our email list atauditor.ca.govFor questions regarding the contents of this report, please contact Margarita Fernández, Chief of Public Affairs, at 916.445.0255This report is also available online at www.auditor.ca.gov Alternative format reports available upon request Permission is granted to reproduce reports

Elaine M. Howle State AuditorJanuary 14, 20212020-301The Governor of CaliforniaPresident pro Tempore of the SenateSpeaker of the AssemblyState CapitolSacramento, California 95814Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:As required by state law, my office conducted an audit of certain judicial branch entities’ compliancewith the requirements of the California Judicial Branch Contract Law (judicial contract law),Public Contract Code sections 19201 through 19210. The judicial contract law requires the JudicialCouncil of California (Judicial Council) to adopt and publish a Judicial Branch ContractingManual (judicial contracting manual) that is consistent with the Public Contract Code andestablishes the policies and procedures for procurement and contracting that all judicial branchentities, including superior courts, must follow.This report concludes that the five courts we reviewed for this audit—the superior courts inAlameda, Contra Costa, Lake, Orange, and San Bernardino counties—adhered to most of therequired and recommended procurement and contracting practices that we evaluated, butthey could improve in certain areas. Specifically, three courts did not always follow required orrecommended payment practices that help to safeguard public funds. For example, the Alamedacourt made 16,000 in questionable payments because it did not match invoices to appropriatesupporting documentation for two payments we reviewed. In addition, four courts have failedto consistently comply with state law requiring them to notify my office when they enter intohigh-value contracts, which limits my office’s ability to identify in a timely and accurate mannercontracts that may warrant review. Finally, two courts could improve their local contractingmanuals by including certain information, such as a policy on legal review of contracts, that thejudicial contracting manual recommends and the courts had no compelling reason to exclude.Respectfully submitted,ELAINE M. HOWLE, CPACalifornia State Auditor621 Capitol Mall, Suite 1200 Sacramento, CA 95814 916.445.0255 916.327.0019 fax w w w. a u d i t o r. c a . g o v

ivReport 2020-301 C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO RJanuary 2021

C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO R Report 2020-301January 2021ContentsSummary1Introduction5Three Courts Did Not Always Adhere toPayment Requirements or Recommendations9Four Courts Failed to Consistently Report High-Value Contracts15Two Courts Lack Recommended Information in Their LocalContracting Manuals19Other Area We Reviewed23AppendixScope and Methodology25Responses to the AuditSuperior Court of California, County of Alameda27California State Auditor’s Comment on the Response From theSuperior Court of California, County of Alameda29Superior Court of California, County of Contra Costa31Superior Court of California, County of Lake33California State Auditor’s Comment on the Response From theSuperior Court of California, County of LakeSuperior Court of California, County of OrangeCalifornia State Auditor’s Comments on the Response From theSuperior Court of California, County of OrangeSuperior Court of California, County of San BernardinoCalifornia State Auditor’s Comments on the Response From theSuperior Court of California, County of San Bernardino3537414345v

viReport 2020-301 C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO RJanuary 2021

C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO R Report 2020-301January 2021SUMMARYFor this fifth biennial audit of the procurement and contracting practices of Californiasuperior courts, we reviewed the superior courts in Alameda, Contra Costa, Lake,Orange, and San Bernardino counties. We determined that these five courts adheredto most of the required and recommended procurement and contracting practices thatwe reviewed; however, they could make certain improvements to better ensure theresponsible stewardship of public funds. We reviewed the selected courts’ practicesrelated to contracts, payments, and purchase card transactions for fiscal year 2019–20.This report concludes the following:Three Courts Did Not Always Adhere to Payment Requirements orRecommendationsPage 9We found that three courts did not always follow established paymentprocedures, increasing the risk of misusing public funds. The Alamedacourt made questionable payments totaling 16,000 because it didnot match invoices to appropriate supporting documentation fortwo of 18 payments we reviewed, and it routinely did not adhereto authorization limits for approving invoices. The Orange courtalso exceeded its authorization limit for one of 10 payments wereviewed, and the Lake court did not fully separate payment dutiesas recommended so that no one person is in a position to initiate orconceal errors or irregularities for six of 10 payments we reviewed. Thecourts whose purchase card transactions met our threshold for review(Contra Costa, Orange, and San Bernardino) generally used purchasecards appropriately. Many of the purchase card transactions we reviewedwere emergency purchases related to the 2019 coronavirus diseasepandemic and were exempt from competitive bidding requirements.The processes courts followed for these emergency transactions and thegoods and services they purchased were reasonable.Four Courts Failed to Consistently Report High-Value ContractsSome courts have not fully complied with state law that generallyrequires them to notify the California State Auditor’s Office (StateAuditor) within 10 business days of entering into contracts estimatedto cost more than 1 million. The Alameda court had four suchcontracts in fiscal year 2019–20 but did not notify us of any becauseit did not have sufficient policies and procedures in place for doingso. The Contra Costa, Orange, and San Bernardino courts did notifyus about some high-value contracts they had in fiscal year 2019–20but failed to notify us about others for various reasons, includingPage 151

2Report 2020-301 C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO RJanuary 2021staff error, a gap in their notification procedures, or incorrectinterpretation of the notification requirement. By not fully complyingwith the notification requirement, these courts have limited ourability to identify in a timely and accurate manner contracts that maywarrant review.Page 19Two Courts Lack Recommended Information in Their LocalContracting ManualsTwo courts do not have information in their local contractingmanuals that would help ensure that their staff members followappropriate contracting processes. The Alameda and Lake courtseach omitted from their local contracting manuals certain provisionsthat the Judicial Branch Contracting Manual (judicial contractingmanual) recommends courts include. Specifically, the Alamedacourt did not identify requirements for legal review of contracts, andboth the Alameda and Lake courts lacked a plan for administeringcontracts. Neither court had a compelling reason for not includingthe recommended information.In addition, we reviewed a selection of contracts from each of thefive courts to determine whether the courts followed requiredprocurement and contracting practices. We found no reportableissues in this area.Summary of RecommendationsAlameda, Lake, and Orange County Superior CourtsTo ensure appropriate expenditures of public funds, the courts should followrequired and recommended practices for approving invoices and separatingpayment duties.Alameda, Contra Costa, Orange, and San Bernardino County Superior CourtsTo comply with the requirements of state law, the courts should implementprocedures to notify the State Auditor within 10 business days of entering intoall contracts estimated to cost more than 1 million and not exempt from thenotification requirement.

C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO R Report 2020-301January 2021Alameda and Lake County Superior CourtsTo ensure staff members have sufficient guidance about appropriatecontracting practices, the courts should include in their localcontracting manuals information that the judicial contractingmanual recommends.Agency CommentsThe courts generally agreed with our recommendations. TheOrange and San Bernardino courts disagreed with certain aspectsof our finding that they did not fully comply with the requirementto notify our office about high-value contracts.3

4Report 2020-301 C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO RJanuary 2021

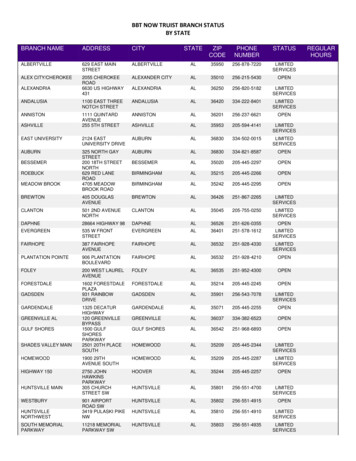

C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO R Report 2020-301January 2021IntroductionBackgroundThe California Judicial Branch Contract Law (judicial contract law) went into effectin 2011. It generally requires all judicial branch entities to comply with the provisionsof the Public Contract Code that are applicable to state agencies and departments andthat relate to the procurement of goods and services. It also requires the Judicial Councilof California (Judicial Council)—which is the policymaking body of the Californiacourt system responsible for ensuring the consistent, independent, impartial, andaccessible administration of justice in the State—to create a contracting manual for alljudicial branch entities, such as superior courts, and for these entities to adopt localcontracting manuals.The judicial contract law also imposes reporting requirements on judicial branchentities. Specifically, it requires that judicial branch entities notify the California StateAuditor’s Office (State Auditor) within 10 business days of all contracts for goods andservices they enter into that involve a total cost estimated at more than 1 millionin value, with limited exceptions such as trial court construction contracts. The lawfurther specifies that all administrative and information technology (IT) projects ofthe Judicial Council or the courts with a total cost estimated to exceed 5 millionare exempt from this reporting requirement and shall be subject to the review of theCalifornia Department of Technology. The law also requires the Judicial Council tosubmit semiannual reports to the Legislature and the State Auditor containing specifiedinformation about most of the judicial branch’s contracting activities. The JudicialCouncil prepares the semiannual reports using information that judicial branch entitiesare responsible for providing to it.In addition, and subject to legislative appropriation, the judicial contract law directsthe State Auditor to audit judicial branch entities other than the Judicial Council everytwo years to assess their implementation of the judicial contract law. This is our fifthbiennial audit report; in all, the five reports so far have covered procurement practicesat 24 of the State’s 58 superior courts since the judicial contract law went into effectin 2011. For this audit, we selected the superior courts in the counties of Alameda,Contra Costa, Lake, Orange, and San Bernardino. We audited two of our selectedentities—the superior courts in the counties of Alameda and Orange—previously, in2014 and 2012, respectively. As state law requires, we based our selection of the courtswe examined on factors including, but not limited to, each court’s size, total volume ofcontracts, previous audits or known deficiencies, and significant or unusual changesin management. Table 1 provides the relative size, workload data, and volume ofexpenditures of the five superior courts we selected for this audit.5

x6Report 2020-301 C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO RJanuary 2021Table 1The Five Courts We Reviewed Varied in Size, Workload, and Volume of ExpendituresCOUNTY SUPERIOR COURTALAMEDACONTRA COSTALAKEORANGESAN BERNARDINO 110,398,000 62,951,000 4,800,000 207,031,000 145,752,000 19,196,000 16,401,000 1,675,000 35,465,000 , total authorized positions as ofJune 30, 20197338412773Court employees, total authorizedpositions for fiscal year 2019–20749337351,5161,098Total expenditures, fiscal year 2019–20Total contract payments,fiscal year 2019–20Case filings, fiscal year 2018–19Source: The Judicial Council’s 2020 Court Statistics Report; the Judicial Council’s Semiannual Report on Contracts for the Judicial Branch for July 1 throughDecember 31, 2019, and for January 1 through June 30, 2020; and the superior courts’ budget reports for fiscal year 2019–20.Note: Data in this table are unaudited and rounded.The Judicial Branch Contracting ManualThe judicial contract law requires the provisions of the JudicialBranch Contracting Manual (judicial contracting manual) to besubstantially similar to those of the State Administrative Manualand the State Contracting Manual and to be consistent withthe Public Contract Code. The State Administrative Manual isa reference resource for statewide management policy, and theState Contracting Manual provides the policies, procedures, andguidelines to promote sound business decisions and practices insecuring necessary services for the State. The Public ContractCode contains, among other provisions, competitive biddingrequirements for public entities. Competitive bidding requirementshelp to provide all qualified bidders with a fair opportunity toenter the bidding process, and to eliminate favoritism, fraud,and corruption in the awarding of public contracts. In additionto establishing procurement requirements consistent with thelaw, the judicial contracting manual also contains recommendedprocurement practices for courts. Although those provisions arenot mandatory, the judicial contracting manual favors the use ofrecommended practices unless courts have good business reasonsfor deviating from those recommendations.Consistent with the Public Contract Code, the judicial contractingmanual generally requires judicial branch entities to securecompetitive bids or proposals for each contract, with certainexceptions, as the text box shows. For example, state law and thejudicial contracting manual exempt purchases under 10,000 fromcompetitive bidding requirements as long as a contracting entitydetermines that the price is fair and reasonable. State procurement

C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO R Report 2020-301January 2021rules and the judicial contracting manual alsodo not require competitive bids on contractsfor emergency purchases or contracts withgovernmental entities.Judicial Purchases That Can Be Exempt FromCompetitive Bidding Requirements Purchases under 10,000The judicial contracting manual also allows several Emergency purchasestypes of noncompetitive procurements. Two types Purchases from government entitiesthat judicial branch entities can use are sole-sourceprocurements and certain leveraged procurement Legal servicesagreements (leveraged agreements), including state Purchases through certain leveragedleveraged agreements. The judicial contractingprocurement agreementsmanual defines a sole-source procurement as one Purchases from business entities operatingin which an entity affords only one vendor thecommunity‑based rehabilitation programsopportunity to provide goods or services after theentity shows appropriate justification for doing Licensing or proficiency testing examinationsso. An entity may use a leveraged agreement to Purchases through local assistance contractspurchase goods and services from certain vendors Sole-source purchaseson the same or substantially similar contractterms as those negotiated by the State or another Purchases from certified small businessesentity without having to seek competitive bids. Purchases from disabled veteran business enterprisesThe Department of General Services administersSource: State law and the judicial contracting manual.some leveraged agreements for use by stateagencies and local governments so that they maybuy directly from suppliers through existing statecontracts and agreements. The judicial contractingmanual includes a process for using leveraged agreements, but itrecommends that judicial branch entities consider whether they canobtain better pricing or terms by negotiating directly with vendorsor soliciting competitive bids.7

8Report 2020-301 C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO RJanuary 2021

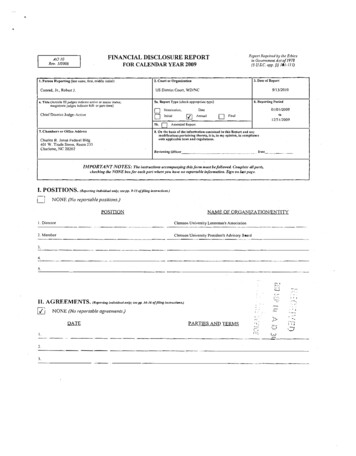

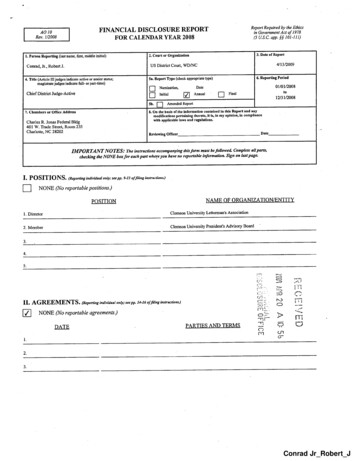

C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO R Report 2020-301January 2021Three Courts Did Not Always Adhere to PaymentRequirements or RecommendationsKey Points The Alameda, Lake, and Orange courts did not always follow required practicesor recommended safeguards when making payments. As a result, each courtincreased its risk of improper payments, and the Alameda court made 16,000 inquestionable expenditures. The courts generally used purchase cards appropriately, and emergency purchasecard transactions related to the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) also appearedto be appropriate and reasonable.The Alameda, Lake, and Orange Courts Did Not Always Follow Payment Safeguards,Increasing the Risk of Improper PaymentsFollowing proper procedures for processing payments, including reviewing the accuracyof invoices, establishing proper levels of approval authority (authorization limits), andseparating invoice approval duties from payment duties, is critical for ensuring thatcourts use public funds appropriately. However, we found that three courts—Alameda,Lake, and Orange—did not always follow these safeguards, which increases the riskof improper payments. Specifically, the Alameda court made roughly 16,000 inquestionable payments in fiscal year 2019–20 because staff bypassed proper safeguardsfor approving invoices. According to the Judicial Council’s Trial Court Financial Policiesand Procedures Manual (procedures manual), which the judicial contracting manualinstructs courts to follow when processing payments, court staff must match invoicesagainst appropriate supporting documentation, such as a contract, to ensure that thecourt is paying the vendor the correct rate for the goods or services provided. However,of the 18 payments (totaling approximately 1.5 million) we reviewed at the Alamedacourt, a division director approved two payments that exceeded contracted rates by 3,330 and 12,690, respectively.1 The two payments were for legal representationprovided by private attorneys. Although the contracts allowed for expenses in excess ofthe contracted rates (extraordinary expenses) if attorneys submitted requests and thecourt approved them, the division director approved the payments without determiningwhether requests had been submitted and approved, and we found that the court had norecord of approval for the extraordinary expenses it paid. The division director indicatedthat she did not request supporting documentation for the 3,330 overpayment becauseshe did not notice the discrepancy between the contracted rate and the invoice rate.For the 12,690 overpayment, she approved the payment on the basis of the attorney’sdeclaration that he provided additional services, not documentation showing thatthe court approved the extraordinary expenses. Because the Alameda court did not1For the five superior courts we reviewed, we began by reviewing 10 payments for each court. If we saw issues that warrantedadditional review of a court’s payment processes, we reviewed eight additional payments.9

10Report 2020-301 C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO RJanuary 2021match the amounts vendors charged to appropriate supportingdocumentation in these two cases, it made payments thatlacked justification.The Alameda court also allowed staff to disregard theirauthorization limits when approving invoices. Specifically, theAlameda court’s accounts payable manual identifies dollar limitsup to which it authorizes court employees in certain positions toapprove invoices for payment. Adhering to such authorizationlimits reduces the court’s risk of making inappropriatepayments, but the Alameda court frequently did not do so. Forthe 18 payments we reviewed, nine court employees approved13 invoices that exceeded their authorization limits by amountsranging from 1,300 to more than 317,000. According to thecourt’s accounts payable manual, an executive, such as the court’sexecutive officer, must approve any payments over 10,000.However, 12 of the 18 payments we reviewed were for invoiceamounts greater than 10,000, and none of the 12 invoices receivedexecutive approval. Rather, managers and directors who had lowerauthorization limits generally approved the invoices. In one case, anonsupervisory staff member with no authority to approve invoicesdid so for an invoice for more than 317,000 from a vendor thatcollects debts owed to the court, without additional review fromhigher-level staff. The court’s executive officer and the court’sfinance and facilities director explained that they intended the courtto adhere to authorization limits when approving the contracts orother underlying agreements associated with these payments, notwhen approving invoices. However, the court’s accounts payablemanual clearly instructs staff to act within the scope of theirauthority when processing invoices, and both the executive officerand finance and facilities director agreed that they should do so.Nine court employees approved 13 invoicesthat exceeded their authorization limitsby amounts ranging from 1,300 to morethan 317,000.The Lake court increased its risk of making improper paymentsby not always fully separating payment duties. According tothe procedures manual, courts must assign work in a mannerthat ensures that no one person is in a position to initiate orconceal errors or irregularities, and the judicial contractingmanual recommends that different employees be responsible forapproving invoices and preparing payments. However, for six of

C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO R Report 2020-301January 2021the 10 payments we reviewed at the Lake court (accounting forapproximately 32,000 of the total 133,000 in expenditures wereviewed), the court’s executive officer approved invoices and alsoposted payments in the court’s accounting system. The executiveofficer stated that this was because the court has limited staffand explained that a staff member other than herself initiallyentered payment information into the accounting system. Becausetwo individuals were thus involved in payment duties, courtstaff members deemed this approach to separating those dutiesadequate. Yet, the executive officer still performed two paymentduties, and a process that does not fully separate payment dutiesis inherently higher in risk than one that does. The court indicatedthat its risk is mitigated because a Judicial Council staff memberprovides quarterly review of the court’s accounts. Nonetheless, itwould be a good practice for the court to take mitigating actions ofits own, and the court sometimes did so. For example, in two otherinstances we reviewed, the executive officer approved invoicesand posted payments, but the court also documented secondaryapproval of the invoices by other staff members. We believe thecourt should consistently incorporate an additional safeguard suchas this when it cannot fully separate payment duties.It would be a good practice for theLake court to take mitigating actions ofits own when it cannot fully separatepayment duties.At the Orange court, we reviewed 10 payments totaling just over 533,000 and identified one instance in which a staff memberapproved an invoice of more than 160,000 for legal serviceswithout seeking executive approval. The court’s accounts payableprocedures manual directs accounts payable staff members toobtain approvals for invoices from managers, using a system thatrequires an additional level of approval by an executive for anypayments exceeding 50,000. However, a supervisor at the Orangecourt informed us that staff who specialize in reviewing courtdocuments, including validating legal invoices (specialists), handlethe approvals for certain invoices, such as those for paymentsto lawyers who provide legal representation for low-incomedefendants, and they do so outside of the system that requires asecond level of approval for invoices totaling more than 50,000.The reason that the court does not process legal invoices throughthe normal system is because of concerns about confidentiality,according to the court’s chief financial and administrative officer.11

12Report 2020-301 C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO RJanuary 2021Although the 160,000 payment we reviewed was appropriateper the terms of the court’s contract, the court bypassed a keysafeguard and increased the risk of improper payments for thisinvoice and others that specialists handled. The chief financial andadministrative officer agreed that the court should incorporateadditional approvals for these types of invoices when they are forpayments above a certain dollar limit, and he said he would havestaff members look into finding a balance between confidentialityand appropriate safeguards.The Courts Generally Conducted Purchase CardTransactions AppropriatelyThe courts whose purchase card transactions we reviewed generallyused their purchase cards appropriately. The state‑administeredprocurement card program, CAL‑Card, is available to all superiorcourts, although they are also allowed to use other purchasecards. The Alameda, Contra Costa, Orange, and San Bernardinocourts used CAL-Cards and other purchase cards, primarily fortravel‑related expenses; the Lake court did not use a purchase card.Proper safeguards over purchase cards help ensure that courtsuse public funds appropriately. When courts make payments thatexceed approved transaction limits on purchase cards or do notfollow judicial contracting manual policies, they may put publicfunds at risk. Because courts provide purchase cards so individualscan make purchases directly from vendors, the cards are subject toabuse if the courts do not strictly oversee their use.We reviewed purchase card transactions at three courts—Contra Costa, Orange, and San Bernardino—because their totalvalue of purchase card payments during fiscal year 2019–20 metour threshold for reviewing individual transactions. The total valueof the Alameda court’s purchase card payments did not meet ourthreshold for reviewing individual transactions. The purchases wereviewed generally complied with applicable requirements. Wereviewed six transactions at each of the three courts, focusing onpurchases that exceeded the 1,500 transaction limit establishedin the judicial contracting manual. The judicial contractingmanual allows courts to deviate from that limit but recommendsthat they document alternative procedures, such as settingdifferent transaction limits, in their local contracting manuals.The Contra Costa and San Bernardino courts adopted the judicialcontracting manual’s limit of 1,500, although they had proceduresallowing approval of higher purchase limits in certain cases. TheOrange court’s local contracting manual set higher transactionlimits ranging from 5,000 to 25,000 for certain staff members,which the court’s chief financial and administrative officerdeemed reasonable given the court’s size and its business needs.

C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO R Report 2020-301January 2021All transactions we reviewed appeared to be reasonable and hadappropriate supporting documentation, such as purchase requestapprovals and receipts for goods.The purchases we reviewed generallycomplied with applicable requirements.Emergency Purchase Card Transactions Related to COVID-19 andExempt From Competitive Processes Appeared to Be ReasonableIn March 2020, the Governor proclaimed a state of emergencyin California to address the global COVID-19 outbreak. Becausethe state of emergency began during our audit period of fiscalyear 2019–20, many of the purchase card transactions we reviewedwere for goods such as hand sanitizer or protective equipment.Most of these purchases were under 10,000 in value, which is thethreshold at which state law and the judicial contracting manual’scompetitive bidding requirements typically apply. Regardless of thevalue of a good or service, state law and the judicial contractingmanual also exempt contracting entities from competitive biddingrequirements when they make emergency purchases that arenecessary for the immediate protection of life, health, property,or essential public services. The urgency of the courts’ COVID-19related purchases, the possibility of increased prices for highdemand goods, and the potential deviation from certain standardpurchasing requirements together introduced additional risk for themisuse of public funds.Despite the increased risk, the COVID-19 related purchases wereviewed appeared to be appropriate. We identified 12 purchasesrelated to COVID-19 among the 18 purchase card transactions wereviewed for the Contra Costa, Orange, and San Bernardino courts.These 12 purchases totaled approximately 65,000. The courtsmade the purchases from March through June 2020 to obtaingoods including hand sanitizing supplies, face masks, and electronicequipment for a virtual courtroom. In each case we reviewed, thecourts had documentation showing the approval of the purchaserequest and the receipt of a good for which the court had areasonable need due to the public health emergency.13

14Report 2020-301 C ALIFO R N IA S TAT E AUD I TO RJanuary 2021RecommendationsAlameda County Superior CourtTo ensure that it expends public funds appropriately, the courtshould immediately require staff to match

CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR Report 020-301 1 January 2021 SUMMARY For this fifth biennial audit of the procurement and contracting practices of California superior courts, we reviewed the superior