Transcription

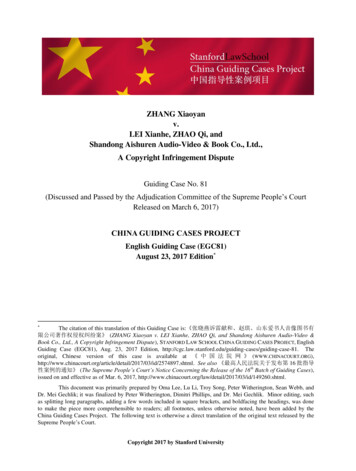

ZHANG Xiaoyanv.LEI Xianhe, ZHAO Qi, andShandong Aishuren Audio-Video & Book Co., Ltd.,A Copyright Infringement DisputeGuiding Case No. 81(Discussed and Passed by the Adjudication Committee of the Supreme People’s CourtReleased on March 6, 2017)CHINA GUIDING CASES PROJECTEnglish Guiding Case (EGC81)August 23, 2017 Edition The citation of this translation of this Guiding Case ��》 (ZHANG Xiaoyan v. LEI Xianhe, ZHAO Qi, and Shandong Aishuren Audio-Video &Book Co., Ltd., A Copyright Infringement Dispute), STANFORD LAW SCHOOL CHINA GUIDING CASES PROJECT, EnglishGuiding Case (EGC81), Aug. 23, 2017 Edition, case-81. Theoriginal, Chinese version of this case is available at 《 中 国 法 院 网 》 icle/detail/2017/03/id/2574897.shtml. See also 《最高人民法院关于发布第 16 批指导性案例的通知》 (The Supreme People’s Court’s Notice Concerning the Release of the 16 th Batch of Guiding Cases),issued on and effective as of Mar. 6, 2017, 9260.shtml.This document was primarily prepared by Oma Lee, Lu Li, Troy Song, Peter Witherington, Sean Webb, andDr. Mei Gechlik; it was finalized by Peter Witherington, Dimitri Phillips, and Dr. Mei Gechlik. Minor editing, suchas splitting long paragraphs, adding a few words included in square brackets, and boldfacing the headings, was doneto make the piece more comprehensible to readers; all footnotes, unless otherwise noted, have been added by theChina Guiding Cases Project. The following text is otherwise a direct translation of the original text released by theSupreme People’s Court.Copyright 2017 by Stanford University

22017.08.23 EditionKeywordsCivilCopyright InfringementHistorical Subject MatterFilm and Television WorksSubstantive SimilarityMain Points of the Adjudication1. For works created based on the same historical subject matter, the main lines of thesubject matter as well as the overall threads and sequences of ideas are common wealth of society,fall within the ambit of thoughts, and cannot be monopolized by individuals. Any person has theright to use such subject matter and to create works [based on it].2. A judgment as to whether a work constitutes an infringement of [copy]rights should bemade from [the following] aspects[:] whether the author of the allegedly infringing work has beenexposed to the right-holder’s work, whether there is [any] substantive similarity between theallegedly infringing work and the right-holder’s work, etc. When determining whether there is[any] substantive similarity [between two works], [a people’s court] should compare the authors’choices, selections, arrangements, designs, etc., as expressed in the works, [to determine whetherthey] are the same or similar; [the court] should not compare such aspects as thoughts, emotions,creative ideas, objects, etc.3. On the basis of the Copyright Law, which provides for the protection of works, apeople’s court should protect the expressions of an author that have originality, i.e., forms ofshowing [the author’s] thoughts or emotions. [The Copyright Law] offers no protection to creativeideas, source material, public domain information, forms of creation, [or] necessary scenes, nor toforms of expression that are unique or limited.Related Legal Rule(s)Article 2 of the Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China1Article 2 of the Implementing Regulation on the Copyright Law of the People’s Republic opyright Law of the People’s Republic of China), passed and issued onSept. 7, 1990, effective as of June 1, 1991, amended two times, most recently on Feb. 26, 2010, effective as of Apr. 1,2010, t ��施条例》 (Implementing Regulation on the Copyright Law of the People’sRepublic of China), passed by the State Council on Aug. 2, 2002, issued on Aug. 2, 2002, effective as of Sept. 15,2002, amended two times, most recently on Jan. 16, 2013, effective as of Mar. 1, 2013,http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2013-02/08/content 2330132.htm.Copyright 2017 by Stanford University

32017.08.23 EditionBasic Facts of the CasePlaintiff ZHANG Xiaoyan claimed: in December 1999, she3 began adapting [a work offiction4] to create the script The Highland Troop.5 In August 2000, [she], based on the script,organized the shooting of 20 episodes of a television series [titled] The Highland Troop(hereinafter the script and the television series thereof are referred to as the “Zhang Series”). InDecember 2000, the filming and production of the series were completed and ZHANG Xiaoyanwas the copyright owner of the series. Defendant LEI Xianhe participated in the filming andproduction of the series The Highland Troop as its honorary producer.Defendant LEI Xianhe, as first screenwriter and producer, and defendant ZHAO Qi, assecond screenwriter, filmed the television series The Last Cavalryman6 (hereinafter the televisionseries and the script thereof are referred to as the “Lei Series”). On July 1, 2009, ZHANGXiaoyan purchased DVD discs of The Last Cavalryman from defendant Shandong AishurenAudio-Video & Book Co., Ltd.7 She discovered that there were many similarities between [theLei Series] and the Zhang Series: the relationships of the main characters, the plots of the stories,and other aspects were the same or similar. [ZHANG Xiaoyan claimed that] the Lei Seriesconstituted an infringement of rights vis-à-vis the script and television series of the Zhang Series.Therefore, [she] requested that the court order the three defendants to cease the infringement ofrights, LEI Xianhe to publish a statement of apology on the Qilu Evening News8 and, LEI Xianheto pay ZHANG Xiaoyan a total of RMB 800,000 as compensation for [her] loss of remunerationfor the script [of The Highland Troop] and [her] loss of fees for publishing and adapting the script[from the below-mentioned work of fiction].9Defendant LEI Xianhe defended his10 position, claiming: the script of the Zhang Serieswas adapted from ZHANG Guanlin’s [work of] long fiction Snowy Plateau.11 The Lei Series was3Feminine pronouns are used to refer to the plaintiff because the name “张晓燕” (“ZHANG Xiaoyan”) ismore commonly found among females.4The work is《雪域高原》(“Snowy Plateau”), as mentioned below; see infra note 11.5The name “《高原骑兵连》” is translated herein as “The Highland Troop” in accordance with a websitehosting the professional profile of actor ZU FENG, at https://upclosed.com/people/zu-feng.6The name “《最后的骑兵》” is translated herein literally as “The Last Cavalryman”.7The name “山东爱书人音像图书有限公司” is translated herein literally as “Shandong Aishuren AudioVideo & Book Co., Ltd.”8The name “《齐鲁晚报》” is translated here literally as “Qilu Evening News”.9In the original judgment, the Supreme People’s Court’s ordered LEI Xianhe and ZHAO Qi to jointly andseverally pay the compensation (“雷献和、赵琪连带赔偿”). See �属侵权纠纷申请再审民事裁定书》 (LEI Xianhe, ZHAO Qi, and ZHANG Xiaoyan et al., The Civil Ruling on an Applicationfor Retrial of a Copyright Infringement Dispute) (2013)民申字第 1049 号 ((2013) Min Shen Zi No. 1049 CivilRuling), rendered by the Supreme People’s Court on Nov. 28, 2014, full text available on the Stanford Law SchoolChina Guiding Cases Project’s website, at n-shen-zi-1049-civilruling.10Masculine pronouns are used to refer to defendant LEI Xianhe (“雷献和”) because the name is morecommonly found among males.Copyright 2017 by Stanford University

42017.08.23 Editioninitially adapted from SHI Yonggang’s [work of] long fiction The Boundless Grey Sky12 by LEIXianhe but the script was rewritten and finalized by ZHAO Qi with reference to [ZHAO Qi’swork of] fiction Carrying a Gun to Travel Around the World on Horseback.13In the first half of 2000, ZHANG Xiaoyan approached LEI Xianhe, proposing to jointlyshoot a television series that reflected cavalry life. LEI Xianhe mentioned to ZHANG Xiaoyan[the fact that] The Boundless Grey Sky was being adapted and proposed to jointly shoot [thisseries], but ZHANG Xiaoyan did not agree. In August 2000, LEI Xianhe and ZHANG Xiaoyansigned a cooperation agreement, stipulating that ZHANG Xiaoyan was to be in charge of filmingand production and LEI Xianhe was to be in charge of military safeguards and was not toparticipate in artistic creation, [and] LEI Xianhe did not see ZHANG Xiaoyan’s script. The LeiSeries and Zhang Series were created for broadcasting at different times and it was not possible forthe Lei Series to influence the release of the Zhang Series for broadcasting.The court handled the case and ascertained:14 the Zhang Series, the Lei Series, Carrying aGun to Travel Around the World on Horseback, and The Boundless Grey Sky are all works onmilitary and historical subject matters [and] take the demobilization ([or] reduction) of cavalryunits during the [military] “streamlining and reorganization” of the mid-1980s15 as the main line.The [work of] short fiction Carrying a Gun to Travel Around the World on Horseback waspublished in the 1996 Issue No. 12 (Overall Issue No. 512) of People’s Liberation ArmyLiterature and Art.16 The [work of] long fiction The Boundless Grey Sky was published by thePeople’s Liberation Army Literature and Arts Publishing House 17 in April 2001. The ZhangSeries was broadcast during the mornings of May 17 through May 21, 2004, by China CentralTelevision18 Channel 8 at the rate of four episodes per day. The Lei Series was broadcast duringthe Golden Time in the evenings 19 from May 19 through May 29, 2004, by China CentralTelevision Channel 1 at the rate of two episodes per day.11The name “《雪域河源》” is translated herein literally as “Snowy Plateau”.The name “《天苍茫》” is translated herein literally as “The Boundless Grey Sky”.13The name “《骑马挎枪走天涯》” is translated herein literally as “Carrying a Gun to Travel Around theWorld on Horseback”.14The original text does not specify which court is referred to here. It is likely meant to be the first-instancecourt of this case, namely, the Intermediate People’s Court of Jinan Municipality, Shandong Province.15The original text reads “二十世纪八十年代” (“the eighties of the twentieth century”) and is translated hereinas “1980s”.16The name “《解放军文艺》” is translated here as “People’s Liberation Army Literature and Art” inaccordance with the translation used on a record concerning the journal, at http://lib.cqvip.com/qk/80005X.17The name “解放军文艺出 版社 ” is translated here as “People’s Liberation Army Literature and ArtsPublishing House” in accordance with the translation used in the record of a book, athttp://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi 10.1.1.169.7179.18The name “ 中 央 电 视 台 ” is translated herein as “China Central Television” in accordance with thetranslation used on the company’s website, at http://tv.cctv.com/cctvnews.19The term “晚上黄金时段” is translated here literally as “the Golden Time in the evenings”. In Chinesetelevision, this prime time generally refers to the time slot from 7 p.m. to 10 p.m.See, e.g.,https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prime time.12Copyright 2017 by Stanford University

52017.08.23 EditionThrough the portrayal of a company commander, an instructor, and a mystical warhorsebefore and after their cavalry company is demobilized, Carrying a Gun to Travel Around theWorld on Horseback describes the glorious history of the cavalry, the demobilization of thecavalry company, and the strong passion felt by the officers and soldiers of the cavalry company,especially the cavalry company commander, towards the cavalry and their warhorses.Carrying a Gun to Travel Around the World on Horseback depicts[, inter alia,] thefollowing: the mysterious background of the mystical horse (No. 15 Army Horse); the perfectharmony between the company commander and his army horse; the character of instructor KONGYuehua; the company commander’s composition of poetry; [the company commander’s] father’sexperience serving as a regiment commander; the significant role to be played by cavalry in futurewars; the efforts made by the company commander to save the cavalry company; the ultimatedemobilization of the cavalry company; and the tragic ending of the company commander and themystical horse.In the Lei Series, the origins of the “heavenly horse” are also mysterious. With respect tothe above-mentioned content of the plot, the Lei Series is basically similar to that of Carrying aGun to Travel Around the World on Horseback, with the exception that the father of companycommander CHANG Wentian was a cavalry division commander [rather than a regimentcommander].The book The Boundless Grey Sky tells a tale, suffused with legend and mystery, about thelast cavalry company in the Chinese army. The book depicts a legendary story about life on thegrassland and in the cavalry (e.g., the emotional [bonds] between humans and horses as well as thegenetic value of the last remaining wild horse), an old man who studies the language of horses, amysterious foreteller, and the last wild horse’s triumph at a Hong Kong racetrack.In The Boundless Grey Sky, the father of [cavalry] company commander CHENG Tian wasthe commander of a former cavalry division. [CHENG Tian’s] commanding officer was the firstcommander of Shannan Cavalry Company and is a former subordinate of CHENG Tian’s father.Since childhood, CHENG Tian has been secretly in love with his commanding officer’s daughter,LAN Jing. Instructor WANG Qingyi and LAN Jing are in love and [WANG Qingyi] works tospark a romance between CHENG Tian and LIU Keke, a geneticist. In the end, companycommander [CHENG Tian] sacrifices his life in order to rescue (a) researcher(s) trapped in aswamp.20In the Lei Series, GAO Bo takes “Da La Ma”, a former instructor’s horse that runs swiftlyand steadily and is good-tempered, and gives it to [company commander] CHANG Wentian toserve as his temporary mount. In the end, the company commander sacrifices himself whilemaking an arrest. The description of the relationship between instructor KONG Yuehua andcompany commander CHANG Wentian in the Lei Series is similar to the plot content regarding20The original text does not distinguish between singular “researcher” and plural “researchers”: �牲”.Copyright 2017 by Stanford University

62017.08.23 Editionthe relationship between instructor WANG Qingyi and company commander CHENG Tian in TheBoundless Grey Sky.The court entrusted, in accordance with law, the Copyright Authentication Committee ofCopyright Protection Center of China21 to carry out appraisals of the Zhang Series and the LeiSeries [and the appraisals yielded] the following conclusions: 1. the setup of the main charactersand their relationships are partially similar; 2. the main threads and sequences of ideas, i.e., thereduction ([or] demobilization) of cavalry units, have similarities; 3. [their] plots are partially thesame or similar, but, with the exception of one verbal expression that is basically the same [in eachseries], the specific expressions of the plots are basically different. The plot [point] with abasically identical verbal expression refers to the statement, made by the male lead of each work,that he is “willing to be a herdsman”. In the fourth episode of the television series of the ZhangSeries, QIN Dongji says: “The greenland is [my] home, [I] treat [my] horse as [my] partner, [Iwant to] be a herdsman.” In the 18th episode of the Lei Series, CHANG Wentian says: “[I] treatthe greenland as [my] home and [my] horse as [my] partner. Have you seen the film TheHerdsman?22 [I want to] be a free herdsman.”23Results of the AdjudicationOn July 13, 2011, the Intermediate People’s Court of Jinan Municipality, ShandongProvince, rendered the (2010) Ji Min San Chu Zi No. 84 Civil Judgment:24 [the court] rejects all ofZHANG Xiaoyan’s litigation requests. Unconvinced, ZHANG Xiaoyan appealed. On June 14,2012, the Higher People’s Court of Shandong Province rendered the (2011) Lu Min San Zhong ZiNo. 194 Civil Judgment: 25 [the court] rejects the appeal and upholds the original judgment.Unconvinced, ZHANG Xiaoyan applied to the Supreme People’s Court for a retrial. 26 On21The name � is translated here as the “Copyright AuthenticationCommittee of Copyright Protection Center of China” in accordance with the translation used in Guiding Case No. SHI Honglin v. Taizhou HuarenElectronic Information Co., Ltd., A Dispute over Computer Software Copyright Infringement), STANFORD LAWSCHOOL CHINA GUIDING CASES PROJECT, English Guiding Case (EGC49), Nov. 15, 2015Edition, case-49.22The name “《牧马人》” is translated herein as “The Herdsman” in accordance with a Wikipedia articleconcerning the movie, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The Herdsman.23In the original text, these quotations appear as “愿做牧马人” (“willing to be a herdsman”), � (“The greenland is [my] home, [I] treat [my] horse as [my] partner, [I want to] be aherdsman”), and �《牧马人》吗 ? 做个自由的牧马人” (“[I] treat thegreenland as [my] home and [my] horse as [my] partner. Have you seen the film The Herdsman? [I want to] be afree herdsman”).24The first-instance judgment has not been found and may have been excluded from publication.25The second-instance judgment has not been found and may have been excluded from publication.26The original text reads “申请再审” (“applied [.] for a retrial”). Article 199 of the Civil Procedure Law ofthe People’s Republic of China provides, inter alia, that a party who considers an effective judgment or ruling to beerroneous may apply to the court at the next higher level for a retrial. See 《中华人民共和国民事诉讼法》 (CivilCopyright 2017 by Stanford University

72017.08.23 EditionNovember 28, 2014, the Supreme People’s Court, after review, rendered the (2013) Min Shen ZiNo. 1049 Civil Ruling:27 [the court] rejects ZHANG Xiaoyan’s application for a retrial.Reasons for the AdjudicationIn the effective ruling, the court opined:28 the focal point of the dispute in this case waswhether the script and television series of the Lei Series infringed upon the copyrights [associatedwith] the script and television series of the Zhang Series.A judgment as to whether a work constitutes an infringement of [copy]rights should bemade from two aspects: 29 whether the author of the allegedly infringing work has ever been“exposed” to the work of the right-holder who demands protection and whether there is [any]“substantive similarity” between the allegedly infringing work and the right-holder’s work.None of the parties in this case disputed [the fact] that LEI Xianhe had been exposed to thescript and television series of the Zhang Series. The key question of this case was whether therewas [any] “substantive similarity” between the two works.The Copyright Law of China30 protects the expressions of an author, in a work, that haveoriginality, i.e., forms of showing [the author’s] thoughts or emotions. [The protection] does notcover the thoughts or emotions themselves reflected in the work. Thoughts, as referred to here,include understandings of material existence, objective facts, human emotions, and thinkingmethods. [Thoughts] are objects that [a person] describes and shows and [they] fall within theambit of subjectivity. Creation is a process that can be perceived by others and during whichthinkers, by means of material media, show ideas by recourse to forms, convert imagery to images,and convert [something] abstract, subjective, or intangible to [something] concrete, objective, ortangible. Expressions which are formed by creation and which have originality are a type of workprotected by the Copyright Law.Expressions protected by the Copyright Law do not merely refer to the text, color, lines,and symbols of the final form [of a work]. When the content of a work is used to manifest theauthor’s thoughts and emotions, the content is also a type of expression protected by the CopyrightProcedure Law of the People’s Republic of China), passed on, issued on, and effective as of Apr. 9, 1991, amendedthree times, most recently on June 27, 2017, effective as of July 1, 2017, http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/xinwen/201706/29/content 2024892.htm.27See �属侵权纠纷申请再审民事裁定书》 (LEI Xianhe, ZHAO Qi,,and ZHANG Xiaoyan et al., The Civil Ruling on an Application for Retrial of a Copyright Infringement Dispute)(2013)民申字第 1049 号)((2013) Min Shen Zi No. 1049 Civil Ruling), supra note 9.28The original text does not specify which court opined. Given the context, this should be the SupremePeople’s Court.29In the Main Points of the Adjudication of this Guiding Case, the aspects to be used are not said to be “two”;moreover, the list of aspects there ends with “等”.30The original text reads “我国” (“my/our country”) and is translated here as “China”.Copyright 2017 by Stanford University

82017.08.23 EditionLaw. However, creative ideas, source material, or public domain information [as well as] forms ofcreation, necessary scenes, or expressions that are unique or limited are excluded from the scopeof protection of the Copyright Law. Necessary scenes refer to certain events, roles, layouts, andscenes that are inevitable and must be used when a certain theme is selected for creation. Suchindispensable ways of giving expression to a particular theme are not protected by the CopyrightLaw. The term “expressions that are unique or limited” refers to [instances] where there areunique or limited forms of expression for a certain thought. These expressions are deemedthoughts and are also not provided with copyright protection.When judging whether there is [any] substantive similarity between the Lei Series and theZhang Series, [a people’s court] should compare the expressions of thoughts and emotions in thesetwo works. [The court should compare] the authors’ choices, selections, arrangements, anddesigns,31 as expressed in the works, [to determine whether they] are the same or similar, ratherthan departing from expressions to look at other aspects, such as thoughts, emotions, creative ideas,objects, etc. [The Supreme People’s Court considered] the following aspects, in combination withZHANG Xiaoyan’s claims, to carry out its analysis and judgment.Concerning the claim made by ZHANG Xiaoyan that the main line of the subject matter inthe Lei Series and [that in] the Zhang Series are the same.Because both the Lei Series and Carrying a Gun to Travel Around the World onHorseback, by closely [following] the theme and situation about “a hero’s dead end, acavalryman’s swan song”, describe stories about “the last cavalryman” before and afterdemobilization, [the Supreme People’s Court] could determine that the main line of the subjectmatter as well as the overall thread and sequence of ideas in the Lei Series are from Carrying aGun to Travel Around the World on Horseback.The Zhang Series, the Lei Series, Carrying a Gun to Travel Around the World onHorseback, and The Boundless Grey Sky are four works that [are] on military and historicalsubject matters [and] take the demobilization ([or] reduction) of cavalry units during the [military]“streamlining and reorganization” of the mid-1980s as their main line. [This main line] iscommon wealth of society and cannot be monopolized by individuals. Therefore, the authors ofthese four works have the right to use, in their own ways, such [historical] subject matter and tocreate works [based on it]. Consequently, even if there exist some similarities between the mainline of the subject matter in the Lei Series and [that in] the Zhang Series, because the main line ofthe subject matter is not protected by the Copyright Law, and the main line of the subject matter inthe Lei Series is from Carrying a Gun to Travel Around the World on Horseback, which was theearliest [of the works] published, [the court] could not determine that the Lei Series was copiedfrom the Zhang Series.31In the Main Points of the Adjudication of this Guiding Case, this list ends with “等”: �择、安排、设计等” (“choices, selections, arrangements, designs, etc.”).Copyright 2017 by Stanford University

92017.08.23 EditionConcerning the claim made by ZHANG Xiaoyan that the setups of the main characters andtheir relationships in the Lei Series and Zhang Series are the same or similarThe aforementioned four works are all on military subject matters [and] take thedemobilization ([or] reduction) of cavalry units during a certain historical period as their main line.Except for Carrying a Gun to Travel Around the World on Horseback, which is limited by thelength of short fiction and, [thus, does not include] any triangular love relationship or relationshipbetween the military and civilians, the other three works all cover such setups of the maincharacters and their relationships as the triangular love relationships, the superior-inferiorrelationships between officials and soldiers, and the relationship between the military and civilians.These ways of depicting [this subject matter involve] necessary scenes that are inevitable and[must be] used in a work about the military subject matter. Because the ways of giving expressionto [this subject matter] are limited, they are not protected by the Copyright Law.Concerning the claim made by ZHANG Xiaoyan that the verbal expressions and the plotsof the stories in the Lei Series and the Zhang Series are the same or similarLooking at verbal expressions, for example, the verbal expressions “be a free herdsman”and “be a herdsman” [used] in the Lei Series and Zhang Series, [respectively,] are basically thesame. However, these verbal expressions are a type of phrase customarily used in a specificcontext; they are not original expressions.Looking at the plots of the stories, a story plot that is used to manifest an author’s thoughtsand emotions falls within the ambit of expression. A story plot that has originality should beprotected by the Copyright Law. However, [if] only some elements of the plots of the stories arethe same or similar, [one] cannot necessarily draw the conclusion that the plots of the stories arethe same or similar. The parts of the aforementioned four works that are the same or similar aremostly a type of public domain source material or source material that lacks originality. In someof [these parts], some elements in the plots of the stories are the same, but the specific content andthe meanings expressed [by these elements] as unfolded by the plots are not the same. Thesecond-instance court determined that six points of the plots of the stories in the Lei Series andZhang Series are the same or similar. Among [these points are] those about the relationship with aformer subordinate, about assigning a temporary mount, etc., and similar plot content also appearsin The Boundless Grey Sky. Although the plot designs in other parts [of the two series] are thesame or similar, some of these merely [show] that a few elements used in the expression of theplots are the same or similar. The parts [of the two series] with the same or similar plot contentare few and insignificant.Overall, [in] the Lei Series and the Zhang Series, the specific unfoldings of the plots aredifferent, the focuses of the depictions are different, the personalities of the lead characters aredifferent, and the endings are different. The plots of the stories of the two [series] that are thesame or similar account for an extremely low proportion in the Lei Series and are of secondaryimportance in its entire story plot. They do not constitute the main parts of the Lei Series and willCopyright 2017 by Stanford University

102017.08.23 Editionnot cause the readers and viewers to have the same or similar experiences in appreciating the twoworks. [Therefore, one] cannot draw the conclusion that the two works have [any] substantivesimilarity.Article 15 of the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on Several IssuesConcerning the Application of Law in the Adjudication of Copyright Civil Disputes32 provides:[Where] works on the same subject matter are created by different authors and theexpression of [each] work is completed independently and has creativity, [a people’scourt] should determine that [each] author enjoys independent copyrights.The Lei Series and the Zhang Series are works on the same subject matter created [independently]by different authors. Accordingly, the two series have originality and [each author] enjoyedindependent copyright.(Adjudication personnel of the effective judgment: YU Xiaobai, LUO Dian, and LI 》 (Interpretation of theSupreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in the Adjudication of Copyright CivilDisputes), passed by the Adjudication Committee of the Supreme People’s Court on Oct. 12, 2002, issued on Oct. 12,2002, effective as of Oct. 15, 2002, 1/content 1462863.htm.Copyright 2017 by Stanford University

Video & Book Co., Ltd.” 8 The name “《齐鲁晚报》” is translated here literally as “Qilu Evening News”. 9 In the original judgment, the Supreme People’s Court’s ordered LEI Xianhe and ZHAO Qi to j