Transcription

The Senate Commission on Animal Protection and ExperimentationAnimal Experimentation in Research

The Senate Commission on Animal Protection and ExperimentationAnimal Experimentation in Research

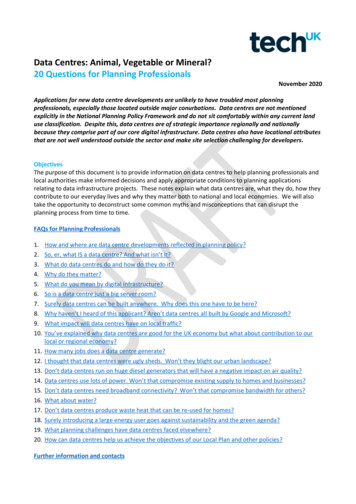

2 ContentsForeword 4Introduction 6Animal experimentation and protection of animals:Ethical considerationsDevelopment of the concept of animal protection in Germany 39Experiments with animals: Definition and figuresEthical aspects of animal experimentation and the principle of solidarity 40What is animal experimentation? 9Transferability from an ethical-legal viewpoint 45How many animals are used in research? 9The Three Rs principle 47What are animals used for in research? 11Alternatives to animal experimentation 51What animal species are used? 11Limitations to alternative methods 55Developments across Europe 13The Basel Declaration 56Animal experimentation in practice: Areas of useBasic research 17Animal experimentation in Germany:From proposal to implementationMedical research 18European regulations on animal experimentation 59Nobel Prize worthy: Outstanding scientific findings 20Animal experiments subject to authorisation 59Diagnostics 21Legal basis 60Transplantation medicine 25Approval procedures 63Cell and tissue replacement in humans 25Conducting animal experiments 64Stem cell research 27Qualified monitoring 68Genome research 28Stress during animal experiments 68Neuroscience 31Animal welfare group lawsuit 71Veterinary research 32Animal experiments in education, training and professional development 35The basic assumption of transferability 35Appendix3

4 ForewordAnimal experiments are essential to basic biological and medical research – creating a classic dilemma as the acquisition of knowledge for the good of mankind places a burden on animals. The protection of animals is high on theagenda of most European countries and sets limits on research. In 2010, following long and controversial discussions, the European Parliament adopteda EU directive on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Thisdirective provides new and more stringent regulations in many aspects, whilealso setting uniformly high standards across Europe for the approval of animalexperiments and the accommodation and care of animals used for researchpurposes.The first edition of Animal Experiments in Research was first published in 2004 bythe Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation).Both the German-language and the English version are no longer available.The amendment to the German Animal Welfare Act in 2013 to bring it in linewith the EU directive resulted in a number of changes to the approval process,placing a greater administrative burden on applicants than before. With thisrevised edition, we aim to present an overview of the current legal requirements, including practical information regarding the organisational processesfor the application and the performance of tests on animals, as well as explainthe legal and ethical principles of research using animal experimentation. Inaddition to the brochure, the DFG website offers further information – scientific papers, legal texts, application forms, etc. – which can be accessed underwww.dfg.de/tierschutz (available only in German).In our society, discussions around animal experiments are controversial andoften very emotional, not least because of the absence of factual informationabout the purpose of the experiments, the burden they place on the animals,or the results and potential benefits. Within the framework of the Basel Declaration, scientists have committed to engage in more communication withthe public and to provide people with more information. This brochure therefore also intends to inform the interested public about the scope and need foranimal testing. On the basis of specific examples and explanations of scientificmethods, we endeavour to explain the principles of experimental animal research and thereby provide a contribution to a more objective debate on thetopic.The brochure is the result of cooperation between members of the DFG SenateCommission on Animal Protection and Experimentation and the DFG HeadOffice in Bonn. At this point, I wish to thank everyone who has contributedto the completion of the project by submitting texts and engaging in criticaldiscussions.I hope that you will find it an illuminating read!Gerhard HeldmaierChairperson of the Senate Commission on Animal Protection andExperimentation of the DFG5

6NOBEL PRIZES1901Emil von BehringThe function of serum therapy,particularly in cases of diphtheria1902Ronald RossScientific researchon malaria1904Ivan PavlovThe physiology of digestion IntroductionThe genetic material of animals contains similar characteristics to the genetic material of humans. Thismakes e.g. the fruit fly a suitable candidate for research into human life processes and diseases.The analysis of the hereditary information (DNA) of complex animals – suchas the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster,the mouse, rat, pig, cow or the humanbeing – is one of the most importantscientific achievements of recent years.Great progress also has been made inother areas of the life sciences, including new insights into the structure of ribosomes (the protein factories of bodycells) and into the astonishing plasticity of stem cells. These findings providenew insights into the complexity ofvital processes, improve medical careand nutrition for human beings andanimals in the long run, and therebycontribute to an increase in the qualityof life and life expectancy.Considerable progress is however notconceivable without the use of animals in research. Only with the helpof animal experiments has it beenpossible to understand human andanimal life processes. This includesthe function of sensory organs and ofthe nervous, hormonal and immunesystems, as well as that of individualgenes, which can only be decodedwithin the context of the total organism. For research of such complexprocesses in the intact living organism,animal testing will also be necessaryin future.There have always been opponentsto animal testing. Now as well as inthe past, opponents have accused re-searchers of viewing human beings assuperior to animals. Another critiquestates that results from animal experiments are not transferable to humanbeings and that animals are made tosuffer solely to satisfy scientific curiosity. From today’s perspective, someanimal experiments conducted in theearly days of animal research do infact seem cruel, although the same istrue of surgical procedures performedon humans. This is mainly due toinsufficient surgical techniques andanaesthetic options at the time. Thediscovery of anaesthesia in the 19thcentury was a godsend for humansand animals alike, and today, its usein animal testing is obligatory as wellas routine.The criticism of animal testing hasled to the formulation of rules governing the use of animals in scientificexperiments as early as the 19th century. These have been continuouslyexpanded ever since. The GermanAnimal Welfare Act is one of the moststringent acts worldwide. It ensuresthat animal tests are conducted onlywithin the confines of socially acceptable norms and are subject to government control. Every animal experiment for biomedical research purposesrequires a written application to thecompetent authority of the relevantstate and must contain a detailed justification for the experiment. An animal welfare committee, consisting ofspecialist researchers as well as representatives from animal protection organisations, advises the authority. Thedecision on the proposal is informedfirst and foremost by an evaluation ofthe indispensability of the experiment.This means that the proposal mustcontain plausible arguments providing evidence that the scientific goalcannot be attained without the use ofanimal tests or alternative methods.In order to safeguard a high bioethicalstandard within animal experimentalresearch across Europe, the EuropeanParliament in 2010 adopted Directive2010/63/EU on the protection of ani-mals used for scientific purposes. Thedirective stresses three principles thatmust be met to ensure animal welfarein scientific research. This is referredto as the Three Rs principle: Reduction and Refinement of experimentalmethods as well as the developmentof Replacement and complementarymethods of animal testing. In addition,the EU directive contains a number ofnew regulations on the approval andperformance of animal tests. In July2013, the German Animal Welfare Actwas revised and adapted to the European directive. Old regulations wereretained and supplemented with newspecifications.7

1905Robert KochTransmission and treatmentof tuberculosisExperiments with animals:Definition and figuresWhat is animal experimentation?The German Animal Welfare Act defines animal experimentation as interventions and manipulations in animalsif this is associated with suffering, painand injury to the animals. This appliesto all procedures subjecting animals tostress “equivalent to, or higher than,that caused by the introduction of aneedle in accordance with good veterinary practice” (Article 3, 2010/63/EU).In reality this means that each procedure carried out on animals for scientific purposes must be recorded as ananimal experiment and approved byan authority. Approval is required forall vertebrates, cephalopods (e.g. octopuses) and decapods (e.g. lobsters).As part of the approval process by thecompetent authority, the reason forthe use of animals as well as their living and care conditions are examined.Approval for an animal test is grantedonly for the purposes expressly specified in the German Animal WelfareAct. This includes basic research, applied research for the prevention,detection and treatment of diseases,quality and efficacy testing of drugs,forensic investigations, environmental protection, promoting animal wellbeing, improvement of animal housing conditions, conservation of species,as well as education, training and professional development.The killing of animals for the sole purpose of organ extraction or the production of cells does not constitute animalexperimentation. Cells or organs areeither examined directly or used tocreate cell and tissue cultures. Such invitro cultures can supplement or partially replace experiments on live animals and make it possible to developalternatives to animal testing. Aboutone-third of all animals used for research purposes is utilised for these invitro methods.How many animals areused in research?The German Ministry of Food and Agriculture and the Federal StatisticalOffice annually record the total number of all animals used in Germany.In 2014, 2.798 million animals wereused for research purposes. Includedin this are 2.008 million animals usedin animal testing and 789,926 usedfor organ extraction. The number ofanimals needed for research purposescorresponds to 0.35% of all 795 million animals used in Germany – thissmall percentage is essential for gaining knowledge about the natural basis of life and for medical progress. At788 million, the largest proportion ofanimals were cattle, pigs, poultry andsheep; these were slaughtered to provide food for human consumption.Another 4 million animals were killed9

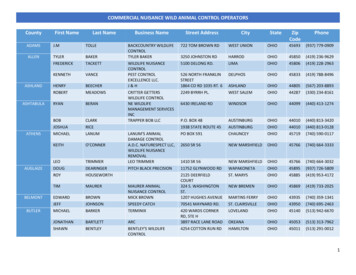

101906Camillio Golgi, Santiago Ramón y Cajal1907The structure of thenervous systemby hunting. Fishing and pest controlalso involve the killing of animals, butthese are not counted.Since 2014, animals used for scientific purposes are registered according to a new Europe-wide reportingprocedure. Newly introduced was theregistration of independently feedinglarval forms. The first count showedthat 563,000 animal larvae were usedAlphonse LaveranThe causative role ofprotozoa in diseasesin scientific research. Fish larvae canbe very small, so that direct countingis not possible and the number of larvae can only be estimated. This initialfigure is not included in the figurespublished by the German Ministry ofFood and Agriculture.There has been a slight decrease inthe overall number of animals usedfor scientific research in recent years:Chart 1:Percentage of animals used for specific research purposesBasic research: 31.1%Translational and applied research: 11.9%28.2%31.1%Conservation breeding programmes of geneticallymodified, burdened animal colonies: 2.8%Quality control, toxicology andother safety evaluations: 23.7%Environmental protection for the benefitof humans and animals: 0.2%1.8%0.3%0.2%Conservation of species: 0.3%11.9%23.7%2.8%Source: Statistics of the German Ministry of Food and Agriculture, 2014Education, training andprofessional development: 1.8%Animals killed for scientific purposes(not animal tests): 28.2%1908Ilya Mechnikow, Paul EhrlichImmunity ininfectious diseasesin 2013 by approx. 3% (2.997 million) compared to the previous year,and in 2014 by another 6.6% (2.798million).What are animals used forin research?The majority of animals in scienceare used in basic research (31.1%)and in “translational and applied research” (11.9%). The latter are projects that test basic research findingsfor medical applications. Basic research and translational and appliedresearch are closely interconnected, and their combined percentagesmake up the expenditure for medicalresearch (43%). Animal experimentation in medical research is conducted to clarify previously unknown lifeprocesses and fundamental biologicalrelationships. In turn, these findingsare used to improve diagnostics andtreatment of human illnesses anddiseases.About 28.2% of animals used in research are not exposed to experimental treatments while alive but are putdown to gain cells or tissues. Thesesamples are used to examine basicbiochemical processes on a cellularlevel and test new pharmacologicaltreatment methods. Ultimately, thispercentage must also be allocated tothe cost of medical research. Numerous animal tests are conductedwithin the framework of consumerprotection and are required by law(so-called “regulatory purposes”).About 23.7% of all test animals inGermany are used for such safetychecks, quality controls or toxicological tests in accordance with thelegislation on chemicals, medicinesand food hygiene. These tests are required for the approval of drugs andother substances with which humanscome into contact.What animal species areused?Animals used in research are mainlysmall mammals such as mice, rats,guinea pigs and rabbits; fish and birdsare used for specific investigations.Mice (1.901 million in 2014, 68%)and rats (13%) are still the mostcommonly used animals and are alsomost often killed for organ extraction.The decoding of the mouse genomea few years ago, and the relativelysimple manipulation of this genomefrom a technical point of view, makesthe mouse by far the most importantresearch species as it offers insightsinto the genetic foundations of lifeprocesses and diseases. The slightdrop in animal experiment numbers over the last two years is mainlydue to a reduction in the number ofmice and rats. The use of fish has in-11

121910Albrecht Kossel1912Cell chemistry andcell nucleus substancecreased over the last few years (currently 9.8%) as the zebrafish genomewas decoded and enabled insightsinto the origins of the life processesin vertebrates. Other species are usedonly to a minor extent. Their numbermay fluctuate slightly, but this has noinfluence on the overall figures.Chart 2:Animal consumption and animal species used for research purposesFood: 99.15%Animals for research purposes (0.35%)Hunting (0.50%)Mice: 68.0%Rats: 13.0%Birds: 2.0%Fish: 9.8%Rabbits: 3.8%Rats: 13%Dogs: 0.1%Mice: 68%Primates: 0.1%Livestock: 0.8%Other animals: 2.4%Source: Statistics of the German Ministry of Food and Agriculture, 2014Alexis CarrelThe development of techniquesfor suturing blood vesselsSince 1991, experiments on greatapes are no longer performed in Germany, and other primates are usedonly in small numbers. In 2014, thefigure was 2,842, which correspondsto about 0.1% of all research animals.The most commonly used monkeyspecies was the long-tail macaque(2,100). In most cases (2,335 animals), primates were used for legallyrequired scientific research, for example in drug testing. Cats playedan even smaller role in research (997animals in 2014), and they too wereused mainly for legally required purposes (519).The use of stray and feral dogs andcats is prohibited in experimentalresearch with animals. They are notsuitable for scientific research as theirorigin, state of health and geneticbackground, as well as their previous behaviour is unknown. Reliableand reproducible research results canonly be achieved under defined andstandardised conditions. This appliesto the status of test animals as wellas all other experimental parameters. Research on wild animals, however,is possible, but severely restrictedand subject to special requirements.To safeguard the protection of species as required by law, additionalapproval by the relevant natureconservation authorities is required.Wildlife research mainly investigatesthe behaviour of animals and theirinteraction with their natural habitats. The findings of such studies areprimarily used to protect species. Inmost cases, the animals are merelybeing observed and only exposed tolow levels of stress so as not to interfere with their natural behaviour.Developments across EuropeThe European Commission also records the number of test animals inorder to track the development within Europe. For 2011 – more recentfigures were not available at presstime – 11.5 million test animals werelisted overall. Germany’s share inthis figure is 2 million animals, because European statistics – in contrast to national records – only countthe actual animal experiments andnot the killing of animals for organextraction.Compared with the last count, therehas been a slight increase in the number of test animals in some countries.In most European countries, how-13

141913Charles Richet Discovery of hypersensitivityto antigensThe number of animal tests with amphibians – including the European tree frog – has more thanhalved across Europe.ever, the number of test animals hasremained fairly constant or has fallen slightly, as in France and the UK.Across Europe, mice are also the mostcommonly used species for animaltesting. Their share is 61%, followedby rats, guinea pigs, other rodents,and rabbits. The share of monkeyswas 0.05%. Great apes have notbeen used since 1999. Since 2008,there has been a drop in the number of amphibians (– 52%), monkeys(– 48%), birds (– 26.5%) and rodents(excluding mice) (– 19.9%), whereasthe recorded numbers of fish ( 29%),rabbits ( 7.5%) and other mammals( 38%) have increased.At the European level, more than60% of animals were used for basicresearch and for the research and development of medical products anddevices for human medicine, dentistry, and veterinary medicine. About19% of all animals were used for testsand checks of medical products anddevices. The number of animals usedin toxicological evaluations and othersafety tests has remained relativelyconstant over the last few years, atabout 9% – despite the introductionin 2006 of the EU’s REACH Directive(Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals),which stipulates that all chemicalsused in larger quantities within theEU require safety information oftenbased on animal studies.15

1919Jules Bordet17Fundamental discoverieson immunityAnimal experimentation in practice:Areas of useBasic researchThe aim of basic research is to gainknowledge and insights. Basic research has no immediate applicationbut provides the scientific basis forfurther research and applications. Because of the similarity between humans and animals in terms of theirmetabolic processes and function oforgans, knowledge gained in animal experiments can provide a betterunderstanding of life processes andtheir disturbances in both humansand animals. Although the transferability of results from basic researchto its application cannot be plannedand its direct short-term benefit cannot be predicted, scientific and medical breakthroughs are not conceivablewithout the knowledge gained frombasic research.Animal testing is a necessity and ofparticular importance where complexrelationships between physiologicalprocesses and diseases can only bestudied on the living organism. Thisapplies in particular to studies on thefunctioning of the nervous, cardiovascular and immune systems, as well asthe action of hormones. Very dynamicdevelopments are currently takingplace in the field of genome and stemcell research. It is hoped that newtherapeutic approaches can emergefrom stem cell research, using cell andtissue replacement to treat heart at-tacks or neurological conditions suchas Parkinson’s disease.Many results in basic research are obtained using cell cultures, because cultured cells develop relatively quicklyand homogeneously and can be directly stimulated with hormones or otherchemicals. Cell cultures are always artificial systems and provide only limited insight into life processes. Yet theyare the only way to directly manipulate and measure biochemical processes in the cell. In cancer research,for example, isolated tumour cells areused to identify the characteristics andcauses of cell degeneration. The truenature of cancer, however, becomesapparent only when its developmentis viewed in connection with othercells and tissues in the body. In orderto trace the development of a tumourin the organism and test therapeuticapproaches, animal experiments arenecessary in which tumour cells aretransferred into mice.The close relationship between cellular basic research and animal testingalso plays a central role in research oninfectious diseases. It is the only pathto understanding how bacteria and viruses infiltrate and attack the animalorganism. Insights into the interactionbetween viruses and their host cellsenable the targeted treatment of virusinfections such as influenza, herpesor smallpox, and the development of

181920August KroghDiscovery of the capillarymotor regulating mechanism1922Archibald Hill, Otto MeyerhofMetabolism and heat generationof muscles1923Frederick Banting, John MacleodDiscovery of insulin Marmots reduce their body functions to a minimum during hibernation. A better understanding of thisprocess could be conducive to saving the lives of seriously injured people.preventive measures. A visible resultof this type of research is the progressmade in the area of vaccinations. Onlya few years ago was it discovered thatpapilloma viruses are involved inthe development of cervical cancer.Without animal experiments on mice,sheep, horses and goats, this discoverywould not have been possible. A vaccine against the viruses was successfully developed. The German virologist Harald zur Hausen was awardedthe Nobel Prize in Medicine for thiswork in 2008.Basic research projects initially aimedat gaining information about life processes in animals may translate intomedical benefits at a later stage. A casein point is the study on the hibernationof marmots and other small mammals.Initially it was assumed that hibernation is triggered by cold temperaturesand lack of food, leading to a failureof the temperature-regulating mechanism. The latest studies of groundsquirrels, dormice and marmots however show that these animals activelystifle their metabolism and regulatetheir body temperature to be nearfreezing, and that breathing and heartrate come to a near standstill. A newway of regulating metabolism wasthus discovered that enables mammalsto switch from “normal operation”to “low flame”. To understand howthis switching process works could belifesaving in the treatment of severeinjuries or in curbing the effects of aheart attack or stroke. Some clinics arealready trying to trigger this processby subjecting patients to low temperatures. Transplantation medicine too(see page 25f.) can benefit by increasing the shelf life of organs.Medical researchMedical progress is inextricably linkedwith basic research. An example ofthis is the development of treatmentmethods for diabetes mellitus. In the1920s, insulin was identified as a hormone that regulates blood sugar levels.Experiments on rabbits, dogs, pigs andcows helped to understand the effect ofinsulin on blood sugar levels and thuscontributed to the development of newtherapies. In 1923, the Canadian scientists Frederick Banting and John J. R.Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prizefor their discovery of insulin. Rabbits,dogs and other mammals have beenlargely replaced by rats and mice inphysiological research. The rapid reproduction of these species permittedspecific breeding for individual clinicalpresentations. This includes, for example, the “diabetes mouse” with raisedblood sugar levels and the “Zucker rat”that develops obesity.Immunology provides numerous examples of the utilization of findingsfrom animal experimentation fortherapeutic applications in humans.Among other topics, immunology examines resistance to pathogens andthe rejection of transplants after implantation. Pioneering advances inmedicine include the development ofthe antiserum to diphtheria (in whichexperiments with guinea pigs wereinstrumental), vaccines against yellowfever and polio (mouse and monkey),19

201924Willem EinthovenElectrocardiogram1926Johannes FibigerDiscovery of the nematodeSpiroptera carcinoma (cancer research) Emil von Behring was the first person to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1901. His serumtherapy, which was tested on animals, is the basis for vaccinations today.studies on the pathogenesis of tuberculosis (sheep and cattle), typhus(mouse, rat and monkey), malaria(dove), as well as antiretroviral agentsto combat AIDS (monkey).The discovery of the effects of vitamin C was studied in the guinea pigand led to the insight that the effect ofvitamins is the same in animals as inhumans. Hormones such as calcitoninfrom salmon are used in the medical treatment of osteoporosis. Animalexperiments have led to the development of new surgical techniques andto the refinement of operating methods. The first experiments on tissuetransplantation were performed in themouse as early as the start of the 20thcentury. These days, animal models(mainly pigs, but also dogs and sheep)are used for kidney transplantation,bone marrow transfer and heart surgery, to develop new methods for thecure or alleviation of organ diseases inhumans. Artificial replacement organs,having first been subjected to standardised technical checks, are tested fortheir biological compatibility in largeanimals such as pigs.Nobel Prize worthy: Outstanding scientific findingsSince the beginning of the 20th century, extraordinary achievements inthe area of physiology and medicinehave been awarded the Nobel Prize.The first Nobel Prize went to the physiologist Emil von Behring in 1901 forhis work on the treatment of diphtheria. At the end of the 19th century,nearly every second child died fromthe disease. In 1890, von Behring andhis Japanese colleague Kitasato foundthat injecting low doses of the diphtheria toxin triggered the formationof antibodies in rats, mice and rabbits.The animals were then protected forlife. Injecting the serum of immunisedanimals also prevented the outbreakof the disease in other animals. VonBehring thus discovered one of thebasic principles of immunology – immunity – and paved the way for thedevelopm

is not possible and the number of lar-vae can only be estimated This initial figure is not included in the figures published by the German Ministry of Food and Agriculture There has been a slight decrease in the overall number of animals used for scientific r