Transcription

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGYVOL. 66, NO. 12, 2015ª 2015 BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY FOUNDATIONISSN 0735-1097/ 36.00PUBLISHED BY ELSEVIER VIEW TOPIC OF THE WEEKBridging AnticoagulationPrimum Non NocereStephen J. Rechenmacher, MD, James C. Fang, MDABSTRACTChronic oral anticoagulation frequently requires interruption for various reasons and durations. Whether or not to bridgewith heparin or other anticoagulants is a common clinical dilemma. The evidence to inform decision making is limited,making current guidelines equivocal and imprecise. Moreover, indications for anticoagulation interruption may beunclear. New observational studies and a recent large randomized trial have noted significant perioperative or periprocedural bleeding rates without reduction in thromboembolism when bridging is employed. Such bleeding may alsoincrease morbidity and mortality. In light of these findings, physician preferences for routine bridging anticoagulationduring chronic anticoagulation interruptions may be too aggressive. More randomized trials, such as PERIOP2 (A DoubleBlind Randomized Control Trial of Post-Operative Low Molecular Weight Heparin Bridging Therapy Versus PlaceboBridging Therapy for Patients Who Are at High Risk for Arterial Thromboembolism), will help guide periproceduralmanagement of anticoagulation for indications such as venous thromboembolism and mechanical heart valves. In themeantime, physicians should carefully consider both the need for oral anticoagulation interruption and the practice ofroutine bridging when anticoagulation interruption is indicated. (J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1392–403) 2015 by theAmerican College of Cardiology Foundation.More than 35 million prescriptions for oralAssociation, American College of Cardiology, Heartanticoagulation (OAC) are written eachRhythm Society, and American College of Chest Phy-year in the United States (1). Conditionssicians have yet to incorporate the findings of thisbeing treated with OAC include atrial fibrillation, me-trial and remain based upon observational studieschanical heart valves, venous or arterial thromboem-and expert opinion (5,6). Yet, the guidelines dobolism, and ventricular assist devices. In any givenlargely agree upon 3 important principles:year, 15% to 20% of these patients will undergoan invasive procedure or surgery that interruptstheir chronic OAC, putting them at increased riskfor thromboembolism (TE), hemorrhage, and death(2,3). Perioperative or periprocedural (hereafter combined simply as periprocedural) anticoagulation management is a common clinical dilemma, often leadingto significant adverse events. The clinical relevanceof this common dilemma and the lack of definitive1. OAC should not be interrupted for procedures withlow bleeding risk.2. Patients at highest risk for TE without excessivebleeding risk should consider bridging. Conversely,those at low risk for TE should not be bridged.3. Intermediate-riskcases(Table1)shouldbemanaged by individually considering patient- andprocedure-specific risks for bleeding and TE.evidence to guide medical decision making hasPatients at low risk for TE should not create afinally led to the conduct of pertinent clinical trials,clinical dilemma. Yet, physician surveys of peri-1 of which has been recently completed (4). How-procedural bridging preferences demonstrate thatever, current guidelines from the American Heartapproximately 30% of physicians choose to bridgeFrom the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City, Utah. Both authors havereported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.Listen to this manuscript’s audio summary by JACC Editor-in-Chief Dr. Valentin Fuster.Manuscript received July 22, 2015; accepted August 3, 2015.Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ by James Januzzi on 09/22/2015

JACC VOL. 66, NO. 12, 2015Rechenmacher and FangSEPTEMBER 22, 2015:1392–403Bridging Anticoagulation1393patients at low risk for TE due to overestimation ofif at all possible. Unless a high bleeding-riskABBREVIATIONSthrombosis risk (7–9). There is even greater hetero-surgery is urgently needed, it is best toAND ACRONYMSgeneity of practice in those patients with intermedi-postpone the procedure until TE risk isate or unclear risks of bleeding or TE. Currentattenuated.evidence, including the recently completed BRIDGEtrial (Bridging Anticoagulation in Patients WhoRequire Temporary Interruption of Warfarin Therapyfor an Elective Invasive Procedure or Surgery) eding rates are significantly higher than thrombosis rates in this group (2,4,10–16).The goal of this review is not to detail the timing,doses, or specifics of bridging anticoagulation. Rather,we will review the data available to specific questionsthat arise in clinical practice to better individualizedecision making and reduce adverse events. We havelimited the scope of the discussion to anticoagulantmanagement. The periprocedural management of antiplatelet agents has been reviewed elsewhere (5,17).CONFIRMING OAC INDICATIONSINR international normalizedratioAVOID OAC INTERRUPTIONSLVAD left ventricular assistdevicePeriprocedural warfarin interruption remainsa routine practice for many clinicians. Recentdata suggest that 40% to 60% of OAC interruptions may be unnecessary (2,12,18). A2005surveyofdermatologicsurgeonsrevealed that 44% of them routinely interruptNOAC novel oralanticoagulantOAC oral anticoagulationTE thromboembolismVTE venousthromboembolismOAC for dermatologic surgery—a procedure with lowbleeding risk (19). Other surveys similarly reveal that90% to 100% of physicians would interrupt OAC andeven bridge patients who are undergoing lowbleeding-risk procedures regardless of TE risk (7,18).OAC should not be interrupted for patients undergoing low bleeding-risk procedures, particularlythose at high risk for TE. Uninterrupted warfarinthroughout the periprocedural period is not associ-When determining the optimal periprocedural anti-ated with elevated bleeding risk for many procedurescoagulation strategy, a critical first step is to fullyand surgeries, especially when a lower interna-appreciate the indication for chronic OAC. In sometional normalized ratio (INR) goal of 2.0 is targetedcases, OAC may no longer be required. For example, a(Tablepatient may present for a procedure who has been onwarfarin therapy can paradoxically reduce peri-warfarin for a single provoked deep vein thrombosisprocedural bleeding relative to interrupted warfarinthat occurred more than 6 months prior. In such awith heparin bridging uation, discontinuation of OAC is most appropriateMoreover, warfarin interruption and reinitiationand will simplify periprocedural anticoagulationcan be associated with an increased incidence ofmanagement.stroke. In 1 retrospective study, warfarin initiationIn some cases, OAC is indicated for acute treatmentmore than doubled the stroke risk during the firstof an existing or recent TE (i.e., in the past 3 toweek compared with nonanticoagulated, matched6 months). Although temporary discontinuation ofcontrol subjects (26,27). This paradox may be due toprimary prevention OAC may be appropriate, treat-early depletion of the vitamin K–dependent factors,ment of an active thrombus should not be interruptedproteins C and S, creating a hypercoagulable milieu.T A B L E 1 Risk Stratification for Perioperative Thromboembolism as Suggested by ACCPIndication for AnticoagulationRisk GroupMechanical Heart ValveAtrial FibrillationHigh* Mitral valve prosthesis Cage-ball or tilting disc aorticvalve prosthesis CVA/TIA 6 months prior CHADS2 score 5 or 6 CVA/TIA 3 months prior Rheumatic valvular heart disease VTE 3 months prior Severe thrombophilia†VTEModerate Bileaflet aortic valve and otherrisk factors‡ CHADS2 score 3 or 4 Low Bileaflet aortic valve withoutother risk factors CHADS2 score 2 orless without prior CVA/TIA VTE 12 months prior withoutother risk factorsVTE 3–12 months priorNonsevere thrombophilia§Recurrent VTEActive cancerData from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines (5). *A true high-risk category may be difficult to objectively define in the absence of trials demonstratingbenefit of heparin bridging in such patients. †Deficiency of protein C, protein S, or antithrombin; antiphospholipid antibodies; multiple abnormalities. ‡CVA risk factors include:atrial fibrillation, prior CVA/TIA, hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure, age 75 years. §Heterozygous factor V Leiden or prothrombin gene mutation.CHADS2 ¼ congestive heart failure, hypertension, age 75 years, diabetes mellitus, and stroke; CVA ¼ cerebrovascular accident; TIA ¼ transient ischemic attack;VTE ¼ venous thromboembolism.Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ by James Januzzi on 09/22/2015

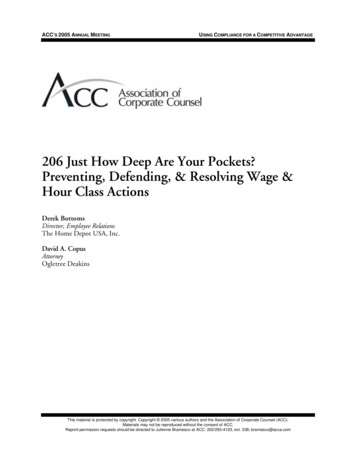

1394Rechenmacher and FangJACC VOL. 66, NO. 12, 2015Bridging AnticoagulationSEPTEMBER 22, 2015:1392–403T A B L E 2 Procedures Amenable to UninterruptedTherapeutic WarfarinEndoscopyBiopsiesEndovascular interventionsStrokes and transient ischemic attacks occurred in 2patients on uninterrupted warfarin (0.3%), with ups.Nevertheless, in many circumstances, interruptionPercutaneous coronary interventionsof chronic anticoagulation will be necessary to avoidCardiac electrophysiology studies and ablationsexcessive procedural- or surgical-related bleeding.Cardiac device implantation (pacemakers, defibrillators,loop recorders)To justify bridging anticoagulation, the risk of TECataract surgerywhile off of anticoagulation should be great enoughDermatologic surgeryto justify the bleeding risk of bridging. However, asDental extractionsoutlined in the following text, the TE risk is generallyEpidural anesthetics and likely other interventional painmanagement techniquesmodest and outweighed by the risk of bridgingassociated bleeding.Minor noncardiac surgeriesTotal knee arthroplastyArthroscopic surgeryWHAT IS THE CLOTTING AND BLEEDING RISKIN THE PERIPROCEDURAL PERIOD?Relatively major operations may also toleratePERIPROCEDURAL TE IS UNCOMMON. The actualcontinuation of OAC. For example, certain orthopedicrate of periprocedural TE for unbridged OAC in-surgeries may also prove tolerant to uninterruptedterruptions is rare, estimated at approximately 0.53%OAC therapy. Rhodes et al. (22) retrospectivelyfrom our review of over 23,000 OAC interruptions inanalyzed 77 patients undergoing total knee arthro-70 studies from 1966 to 2015 (Table 3, Figure 1A)plasty; 38 patients remained on warfarin throughout(2,4,10–16,28). From the same database, the rate of TEthe perioperative period. They found no significantfor patients who are bridged is slightly higher atdifference in the rates of blood transfusion, wound0.92%. The actual rate is likely higher in the absencecomplications, or reoperation between the 2 groups.of bridging but is biased in these observationalRandomized studies appear to confirm these observations. Two randomized prospective trials havestudies by the clinician’s impression of greater TE riskthat drives the decision to bridge.been conducted to directly compare the safety andRates of bleeding and TE vary by OAC indicationefficacy of uninterrupted warfarin versus bridging(Figure 1B). For atrial fibrillation, an individual’s dailywith heparin. In a 2007 study, 214 patients on OACrisk of stroke or transient ischemic attack can beundergoing dental extraction were randomized toapproximated by dividing the annual stroke risk byeither continue warfarin or to stop warfarin and365 days. Although one might expect more thrombosisbridge with heparin (23). Interrupted warfarin withoutin the periprocedural period by invoking Virchow’sbridging was not studied. There were no TE events intriad, observational studies have not borne thiseither group, consistent with the low rate of TE seenhypothesis out. For example, in ORBIT-AF (Outcomesin other studies. Importantly, nearly one-half of theRegistry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrialpatients were at presumably high TE risk, with eitherFibrillation) (2), the periprocedural cohort observed aprosthetic valves or atrial fibrillation with valvular0.35% 30-day stroke rate. Using the average ORBIT-AFdisease. The rate of bleeding was also similar betweenCHA2DS2-VASc score of 4.1, corresponding to anpatients with uninterrupted warfarin versus thoseannual stroke risk of approximately 4.2%, the calcu-with heparin bridging (7.34% vs. 4.76%, respectively;lated 30-day stroke risk is surprisingly similar at 0.35%.p 0.05).For mechanical heart valves, the perioperative riskBRUISE CONTROL (Bridge or Continue Coumadinof TE is approximately 1% (11). Older studies (mostlyfor Device Surgery Randomized Controlled Trial),from the 1970s and 1980s) suggested a higher inci-published in 2013, randomized 681 high-risk patientsdence of perioperative TE. However, these olderundergoing pacemaker or defibrillator implantationstudies included patients with higher-risk valves,to either uninterrupted OAC or interrupted OAC withsuch as cage-ball and tilting disc valves, which wouldheparin bridging (20). Due to the high TE risk of thehave been far more common in that time period (29).study population, there was again no arm of inter-In a more contemporary study of 45 patients withrupted OAC without bridging. The investigators foundmechanical aortic and/or mitral valves who werethat heparin produced more than 4 as many clini-undergoing central nervous system surgeries be-cally significant pocket hematomas than in those ontween 2004 and 2012, there were no TE events duringuninterrupted warfarin (16% vs. 3.5%; p 0.001).an average anticoagulation gap of 7 days (14). MoreDownloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ by James Januzzi on 09/22/2015

than one-third of these patients were not bridged. Ofnote, 20% of these patients experienced a majorbleeding event.Regarding venous thromboembolism (VTE), arecent observational study of 1,257 patients foundonly 6 recurrent VTE events (0.4%) during the periprocedural period (12). Of the 236 patients at moderate to high risk of recurrent VTE, there was only 1event. Two-thirds of these patients were not bridged.No difference in recurrent VTE was detected betweenthe bridged and nonbridged groups.Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) are anincreasingly common indication for OAC. Management of periprocedural anticoagulation in LVADpatients is complex and consensus is lacking (30).Cumulative TE rates are surprisingly modest despitelikely frequent subtherapeutic INRs (extrapolatingfrom the experience in anticoagulation clinics). Boyleet al. (31) showed that, in 331 patients with HeartMate IILVADs (Thoratec, Pleasanton, California), the rate ofTE (ischemic stroke and pump thrombosis) was 1.5%over the course of a year (31). Thrombotic eventscorrelated with an INR 1.5, and hemorrhagic eventswith an INR 2.5. Meanwhile, major hemorrhageoccurred 6 more frequently than TE. Another retrospective study examined patients who, for variousreasons, never achieved a post-operative partialthromboplastin time 40 s after implantation of aHeartMate II. Although the stroke and pump thrombosis rates were high, subtherapeutic patients did noworse than fully anticoagulated patients. However,they experienced an absolute risk reduction of 11%fewer hemorrhagic events than their anticoagulatedRE-LY ¼ Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy With Dabigatran Etexilate.Values are n or % (n) unless otherwise indicated. *Denominator differs from number of cases stated (12,278) due to heterogeneity of definitions and reporting of events between studies reviewed. †Dunn et al. (16) excluded from combined totals to represent the mostcurrently relevant data.7.332.8 (255)11.8 (1,083)18.6413.3 (122)24.1 (216)2.32.381.3 (12)1.2 (110)3.2 (29)3.5 (323)0.710.390.4 (4)0.52 (65)0.94 (93)0.3 (3)1,81322,334Review1Randomized controlled trial2001–20152015Combined†BRIDGE 71.8 (58)6.6 (53)0.710.5 (17)1.5 (12)4,1061Post-hoc subgroup analysis2005–20082015RE-LY (28)7.560.940.2 (2)Unavailable2.7 (15)Unavailable0.820.00.2 (2)Unavailable2.2 (12)Unavailable0.170.000.2 (3)Unavailable0 (0)Unavailable451,812Retrospective Cohort1Retrospective cohort2004–20122015Cavalcanti et al. (14)Clark et al. (12)20152006–201211.8 (31)1.7Prospective cohortSteinberg et al. (2)20152010–201112,2800.8 (4)0.5 (9)0.573.6 (18)1.2 (20)3.7 (19)1.9 (100)Unavailable11.6 (833)2.7*0.9 (18)*3.3 (211)*UnavailableN/AUnavailableUnavailable0.85*0.6 (32)*1.0 (73)*0.6 (1)1,17612,278Meta-analysis31Systematic review1966–20012012Siegal et al. (10)Dunn et al. (16)20032001–2010340.6 (6)0.60Not BridgedNot BridgedBridgedNot BridgedBridgedStudy TypeStudy PeriodYear PublishedStudy/First Author (Ref. #)Any BleedingBridgedTotal%Major BleedingThromboembolic EventsTotal%Numberof CasesNumber ofStudiesT A B L E 3 Summary of All Studies Examining Periprocedural Complications by Anticoagulation Strategy From 1966 to 20152.19Bridging AnticoagulationN/ARechenmacher and FangSEPTEMBER 22, 2015:1392–403Total%JACC VOL. 66, NO. 12, 2015counterparts (32).BLEEDING IS MUCH MORE COMMON THAN CLOTTING.On average, the most recent studies demonstratea periprocedural bleeding-to-thrombosis ratio ofapproximately 13:1 with bridging and 5:1 withoutbridging (Figure 1), suggesting that the net effect ofbridging is unbalanced toward bleeding (2,10–15). Ina large systematic review and meta-analysis of 34observational studies of bridging anticoagulation,Siegal et al. (10) found an odds ratio of 3.6 (95% confidence interval: 1.52 to 8.50) for major bleeding withbridging versus nonbridging, and no significant difference in TE or mortality (Figure 2) (10). Because asystemic embolic event is often far more devastatingthan bleeding, an elevated bleeding-to-thrombosisratio may be acceptable. However, a 13:1 ratio forbridging anticoagulation is likely inconsistent with thestandard of primum non nocere, or “first, do no harm.”BLEEDING MAY BE A BIGGER THREAT THAN CLOTTING.Bleeding is increasingly recognized as a marker ofDownloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ by James Januzzi on 09/22/20151395

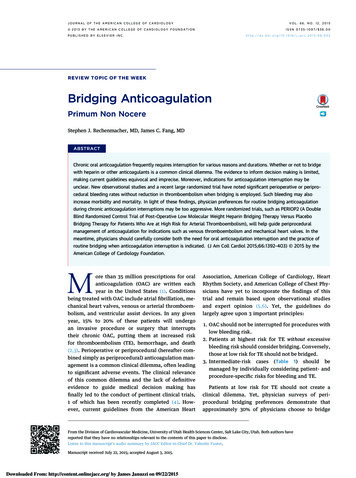

1396Rechenmacher and FangJACC VOL. 66, NO. 12, 2015Bridging AnticoagulationSEPTEMBER 22, 2015:1392–403(p 0.003). Also, compared with uninterruptedF I G U R E 1 Rates of Periprocedural Thromboembolism and Bleedingwarfarin, bridging anticoagulation correlates withincreased hospital cost ( 41.72 37.81 vs. 1,114.60 11.83%A 12% 164.90) (21).Despite the evidence that: 1) TE events are rare inThromboembolism10%the periprocedural period; 2) hemorrhage is far moreMajor Bleedingcommon than TE with bridging; and 3) there is noAny Bleedingclear antithrombotic benefit with bridging, it remainsEvent Rate8%a common and highly variable practice.6%3.52%4%CONTEMPORARY BRIDGING PRACTICES ARE2.80%2%0.52%0%HIGHLY VARIABLE1.18%0.94%TraditionalNot Bridgedcontemporaryanticoagulationclinicsreport an average time in therapeutic range of onlyBridged65% (38). In 1 study, 23% of INR values were below 2.0B(39). Therefore, the average patient on chronic4%warfarin therapy spends more than 84 days/year in aThromboembolism3.32%subtherapeutic range. Yet, cumulative annual TEMajor Bleeding3%rates are modest at approximately 1% when all pa-Event Ratetients with atrial fibrillation in such programs are2.26%considered (40). It is worth noting that the lengthof time warfarin is interrupted for a procedure is2%typically 5 days (13). Although it is not common1.13%1.14%1%practice to bridge subtherapeutic patients in theoutpatient setting, many clinicians default to bridging0.76%0.65%during these short periprocedural periods—ironically,0%a time when patients are at greater risk of bleeding.AfibVTEMechanical ValvesThe threshold for brid

Mechanical Heart Valve Atrial Fibrillation VTE High* Mitral valve prosthesis Cage-ball or tilting disc aortic valve prosthesis CVA/TIA 6 months prior CHADS 2 score 5 or 6 CVA/TIA 3 months prior Rheumatic valvular heart disease VTE 3 months prior Severe thrombophilia† Moderate Bileaflet ao