Transcription

NEUROTRANSMISSIONSFALL 2017DEPARTMENT OF NEUROLOGYADMINISTRATIONBruce R. Ransom, M.D., Ph.D.Warren and Jermaine Magnuson Professorand Chair,Department of NeurologyService Chief, Neurology,UW Medical CenterSidney M. Gospe, Jr., M.D., Ph.D.Herman and Faye Sarkowsky Chair,Child NeurologyProfessor of Neurology and PediatricsDivision Head, Pediatric Neurology, SeattleChildren’s HospitalWill Longstreth, M.D.Professor of NeurologyService Chief, Neurology,Harborview Medical CenterJana Pettit, M.B.A.DirectorKass KlemzAssistant to the ChairNEUROTRANSMISSIONSEDITORIAL BOARDBruce R. Ransom, M.D., Ph.D.Nicholas P. Poolos, M.D., Ph.D.Megan SchadeDEPARTMENT OF NEUROLOGYUNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON SCHOOLOF MEDICINE1959 NE Pacific St.RR650 Box 356465Seattle, WA 98195Phone 206.543.2340Fax 206.685.8100depts.washington.edu/neurologFrom the ChairWelcome to the Fall 2017 issue ofNeurotransmissions, the UW Departmentof Neurology’s newsletter for colleagues,alumni and friends. I am proud to sharethe latest exciting developments in ourdepartment, including news on research,clinical resources, and education.was a UW Neurologytrainee who wenton to subspecialitytraining in infectiousdisease. She and herlaboratory personnelseek to understandwhy neurosyphilis—apotentially devastatingBruce R. Ransom,neurological disease—MD, PhDoften occurs inthe context of HIV infection, and why itsclinical manifestations are more severe inthat setting. Her work has garnered abundantfunding from the NIH, and she has becomean internationally recognized expert in thisdisorder.In this issue we spotlight the UW HeadacheClinic, the only academic headache centerin the WWAMI region, and a uniqueclinical asset. The Headache Clinic is led byDrs. Natalia Murinova and Jenna Kanter.They are bringing innovative practices tothe stubborn problem of refractory migraineand cluster headache, including shared visitswith allied practitioners focused on lifestylemodification to improve headache control.This holistic approach has won rave reviewsfrom their patients, and clinical volumes arebooming, especially at the Eastside SpecialtyCenter. Head to our feature on page twoto learn more about this unique resourcewithin UW Neurology.Finally, do not miss the latest installment ofPhil Swanson’s History of Neurology. In thisissue, he describes the growth of the Divisionbeginning in 1967 when Phil took over asChief at the “tender age of 34.” Neurology atthat time had five faculty members aside fromPhil, and believe it or not, no full-time facultyat Harborview. Over the next several years,a number of new faculty joined the Division,and you will recognize their names as storiedcontributors to our neurological past. You willsee them in their youthful glory ca. 1970when you turn to page four.On the research front, Professor and ViceChair for Academic Affairs ChristinaMarra, MD runs a highly successfulprogram into the surprisingly commonproblem of neurosyphilis. Dr. MarraINSIDE THIS ISSUEPAGE2Headache ClinicPAGEPAGE3Christina Marra, MD4Neurology Division in 1970a

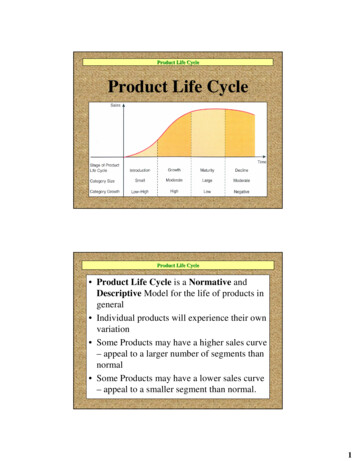

The UW Headache Clinic:innovative treatments for a vexing disorderMigraine is one of the leading causes ofdisability worldwide. It disproportionatelyaffects patients in young adulthoodand middle age, and results in billionsof dollars of lost productivity annuallyin the US alone. While many effectivetreatments are available for migraine andother headache disorders, many patientscontinue to struggle with pain anddisability due to delays in diagnosis andlack of appropriate treatment.The UW Headache Clinic is currentlythe only university-based clinicspecializing in headache disorders inthe Pacific Northwest and the entireWWAMI region. The clinic is proud tooffer multimodal headache management,and emphasizes patient education andempowerment as integral componentsof the treatment plan. In addition tomigraine, the Headache Clinic alsospecializes in less common headachedisorders such as cluster headache.Patients who are referred to the clinic areasked to fill out a comprehensive onlinequestionnaire reviewing their preferencesfor treatment, headache history, andother aspects of their medical and socialhistory. Having this information inadvance allows the providers to tailorthe initial consultation to the individualpatient’s needs. Additional questionnairesare sent before each follow-up visit,promoting efficient clinical care and alsoallowing outcomes to be tracked overtime. New patients are typically seenby a team of a neurologist and a nursepractitioner to review their headachehistory and establish an accuratediagnosis and preliminary treatmentplan. Next, patients with a diagnosis ofmigraine attend a shared medical visit2 DEPARTMENT OF NEUROLOGYMembers of the UW Headache Clinic team, from left to right: Natalia Murinova, MD;Mui Chan-Goh, ARNP; Jenna Kanter, MD; Melissa Schorn, DNP; Debbie Nesbitt, ARNP.led by Natalia Murinova, MD, ClinicalAssociate Professor of Neurology, andMelissa Schorn, DNP, where they learnmore about the pathophysiology of migraineand the spectrum of treatments availableat the Headache Clinic. A similar sharedvisit led by Jenna Kanter, MD, ClinicalAssistant Professor of Neurology, and MuiChan-Goh, ARNP is offered for patientswith cluster headache.Lifestyle factors including sleep, exercise,and diet are crucial for successfulheadache management. Due to timeconstraints, however, these issues areoften deprioritized in the traditionalmodel of one-on-one patient care. TheHeadache Clinic under the leadershipof Dr. Murinova is pioneering the useof shared medical visits to provide morecomprehensive patient education andmotivation to address lifestyle factors:Melissa Schorn leads shared medicalvisits devoted to nutrition, while FlaviaConsens, MD, Associate Professor ofNeurology, and Mui Chan-Goh leadshared visits focused on sleep hygiene.The Headache Clinic plans to developadditional sessions devoted to other topicssuch as physical activity. Early feedbackon these visits has been overwhelminglypositive: patients value the in-deptheducation provided, as well as theopportunity to learn from the perspectivesand questions of their peers.Studies have found a high prevalenceof mental health comorbidities such asanxiety and depression in patients withmigraine, and these comorbidities arealso known to be associated with higherlevels of migraine-related disability anda higher risk of progression to chronicmigraine. Stress is the most commontrigger identified by patients with migraine.Behavioral approaches to headachemanagement are safe and effective, howeveraccess to these methods in the communityis limited, especially for patients with publicinsurance or limited financial means.Because of this unmet need, the HeadacheContinued on page 8

Two Decades of Researchon Syphilis and HIVBy Christina Marra, MD, Professor and Vice Chair of NeurologyAfter my Neurology residency at UW, Ibegan a fellowship in Infectious Diseasesat UW. One of my tasks was to attendin the STD Clinic at Harborview,which increased my interest in sexuallytransmitted diseases. I went to graduateschool before medical school, and I neverthought that I would work in the labagain. But under the mentorship of SheilaLukehart, PhD, in Infectious Diseases, Ibegan laboratory-based studies of syphilisand neurosyphilis. While many think ofsyphilis as a disease of purely historicalinterest, this is far from the truth. Forexample, between 2000 and 2016, therate of infectious syphilis in the UShas increased more than 300%; similarincreases have been seen worldwide.In the US, about half of those withsyphilis are also infected with the humanimmunodeficiency virus (HIV).Early in the HIV epidemic, reports ofincreased risk of neurosyphilis and poorerserological response to syphilis treatmentin HIV-infected compared to HIVuninfected individuals piqued my interest.Between 1996 and 2014, my research groupconducted an NIH-funded observationalstudy of syphilis and neurosyphilis. Overall,we enrolled 760 HIV-infected and 220HIV-uninfected individuals with syphiliswho underwent a structured medicalhistory and neurological examination,blood draw and lumbar puncture forcollection of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).Over 120 participants re-enrolled in ourstudy with one or more repeat episodes ofsyphilis.We identified risk factors for neurosyphilisin HIV-infected and HIV-uninfectedindividuals, and we showed that HIV-infected individuals with neurosyphilishad poorer treatment responses than theirHIV-uninfected counterparts. The syphilisbacterium (Treponema pallidum subspeciespallidum or T. pallidum) is cleared fromsites of infection by macrophages thatingest and kill it when it is coated withopsonic antibody. We showed that,compared to HIV-uninfected individualswith syphilis, HIV-infected persons withsyphilis have reduced T. pallidum opsonicantibody activity in serum. This findingmay provide a mechanism to explaindifferences in the clinical course ofsyphilis in HIV-infected individuals.In a separate group of HIV-infectedindividuals, we found that those withprevious syphilis performed morepoorly on neuropsychological tests thanindividuals who had never had syphilis.This finding is important because itsuggests that an inflammatory insult mayworsen current HIV-associated cognitiveimpairment. With Dr. Emily Ho, werecently added support to this hypothesisusing our syphilis cohort. We showed thatHIV-infected individuals with neurosyphilishave increased CSF concentrations ofCXCL10 and CCL2, two chemokines thatare associated with HIV-related cognitiveimpairment.We currently have two ongoing NIHfunded studies. One addresses the bestclinical practice for evaluation of patientswith syphilis. Specifically, we hope todetermine whether lumbar puncture, withtreatment based on CSF findings, improvesserological, cognitive and functionaloutcomes in patients with syphilis. Theother study is more laboratory-based, andinvestigates the impact of differences in theinnate and acquired immune response onrisk of neurosyphilis.In 2014, I received the Achievement Awardfrom the American Sexually TransmittedDiseases Association for our body of workon syphilis and neurosyphilis. The effortsContinued on page 8Front from left to right: Shelia Dunaway, Haley Mendoza, Christina MarraBack from left to right: Sher Story, Arielle Davis, Lauren Tantalo, Sharon Sahi3

Swanson’s History of NeurologyThe Bronze Age of UW Neurology: Part 3. 1967-1974By Phillip D. Swanson, MD, PhD,Professor of NeurologyIn 1967, I became the fourth DivisionHead of Neurology at UW whichconsisted of five other facultymembers at the time: August (Gus)Swanson, then Associate Dean forAcademic Affairs who continued someclinical activities; Henry Leffman,a clinical neurologist at the VA;Coldevin (Coley) Carlson, head ofChild Neurology, then based at theUniversity Hospital; John (Tim)Chapman, a pediatric neurologist atChildren’s Hospital who had a clinicalappointment, and John R. Green, ajunior faculty member who had finishedhis residency in 1965 and showed aninterest in epilepsy. There was nofull-time neurologist at the busiesthospital, King County Hospital (nowHarborview Medical Center). Twoadditional neurologists who would playkey roles in developing UW Neurologywere S. Mark Sumi, trained as botha neurologist and neuropathologist,and Wayne E. Crill, a neurologistand superb basic neurophysiologist.Mark Sumi had returned to Seattlein 1966 after two years studyingneuropathology at the Max PlanckInstitute in Munich, Germany. Hehad dual appointments in Pathologyand Neurology, but needed to take aWashington licensing examinationbefore he could practice clinicalneurology. Wayne Crill, a UW medicalschool graduate, had returned toSeattle after neurology residency underFred Plum at Cornell. Wayne began aresearch fellowship in the Departmentof Physiology and Biophysics chairedby Harry Patton, PhD. Wayne’s initialresearch, in collaboration with Dr.4 DEPARTMENT OF NEUROLOGYThelma Kennedy, was to investigatethe physiology of cerebellar climbingfibers. He began seeing patients in theNeurology outpatient clinic at UWMC.In 1967, the residency programwas largely financed by a ClinicalNeurology Training Grant from theNIH. This grant program began inthe early 1950s and was designed toencourage medical schools to developprograms for training academicneurologists by contributing supportto faculty and stipends for neurologytrainees for whom previously therehad been little hospital support.Training grants now becameavailable for neurology, neurosurgery,neuropathology, and neuroradiology.There was no national matchingprogram for neurology residencypositions, though medicine internshipswere distributed through the NationalMatching Program.Neurology research programs.Research activities at UniversityHospital (now UWMC) and theSeattle VA were primarily in the areaof neurochemistry. William Stahl,PhD, a biochemist with expertise inNeurochemistry from his post-doctoralwork in Henry McIlwain’s laboratoriesin London, followed by two years inthe NIH Laboratory of Neurochemistryunder Eberhard Trams, joined usthat year. His primary laboratory wasnewly established at the Seattle VA,and was supported by VA researchfunding. He collaborated with mylaboratory at the University Hospitalin exploration of energy-utilizingprocesses in the CNS, especially cationtransport. We also collaborated withresearchers in Neuropathology suchas Dr. E.C. (Buster) Alvord Jr, and Dr.Sumi. We were the first to show thatthe post-mortem human brain could bedivided into subcellular fractions suchas microsomes and mitochondria. Weapplied these techniques to the brains ofpatients with Huntington’s Disease andcerebro-tendinous xanthomatosis, thelatter found to be a leukoencephalopathyassociated with storage ofdihydrocholesterol (cholestanol).Donald F. Farrell joined the Division in1971. After his neurology residency atStanford, Don completed a fellowship atJohns Hopkins, developing an interest instudying lipid storage disorders such asKrabbe disease.Neurology clinical services. Eventhough we were a Division withinthe Department of Medicine, wehad autonomy on the inpatient andoutpatient services. Residents rotatedat HMC, UH, Children’s, Seattle VA,and the USPHS hospital. Rotationswere usually for three-month blocks.Outpatients were seen in clinics atthe hospital to which the resident wasassigned. There was no continuity clinic,but residents did have continuity withdischarged inpatients. Non-clinicalrotations included neuropathology for sixmonths, and electrophysiology with anemphasis on EEG. Pediatric neurologywas a three-month block rotation foradult residents, who were paired with asenior pediatric neurology fellow. Thenumber of residents was usually three orfour at each level of training.

Division of Neurology faculty in 1970. Shown are faculty from left to right, beginning withTop row: Luke Kao, Jim Coatsworth, Herb Goldston, Bill Bozarth, Mike Copass, Dick Matthews.Middle row: Bill Stahl, Bob Wilkus, Bob Gotshall, Bill Kuhn, Vicki Boyd. Bottom row: John Green,Mark Sumi, Wayne Crill, Phil Swanson, Henry Leffman, Gil FrankKing County Hospital (HarborviewMedical Center). Even though KingCounty Hospital had the busiestclinical service, there were no full-timeNeurology (or Neurosurgery) facultylocated on-site. In 1969, Dr. Sumiagreed to assume the role of Chiefof the Neurology Service. At thattime, much of the attending at HMCwas done by community neurologistssuch as William Sata, Bob Rankin,Bob Aigner, and Bob Colfelt. Thesevolunteer faculty usually made roundson Tuesdays and Thursdays. Dr. Sumiincreased attending rounds to threeor more times per week. At aboutthe same time, during the Presidencyof Lyndon B. Johnson, the RegionalMedical Program (RMP) was createdwith the goal of improving care forpeople with cancer, heart disease, andstroke. We obtained an RMP contractto improve stroke education andtreatment in the Northwest includingAlaska. Dr. Gilbert Frank, a neurologistwho had come from Iowa to join theEEG unit, changed direction to developa stroke program at HMC. He createdteaching materials and undertooktrips to southeast Alaska to consulton stroke-related issues. We obtainedoffice space for the stroke programand for the Neurology Division on thefifth floor of Harborview Hall. WhenMike Copass completed his residencyand a neuropathology fellowship in1973, he joined HMC Neurology andbecame heavily involved in developingthe Medic One program for earlyintervention in outside hospitalresuscitation protocols. The present twoneurology inpatient services are namedthe Sumi and Copass services to honorthese two pioneers.U.S. Public Health Service Hospital(USPHS). In 1966, Robert Gotshallcame to Seattle to join the InternalMedicine program at the US PublicHealth Service Hospital (now PacificMedical Center) on Beacon Hill. Bobdecided to train as a neurologist andthen he joined our faculty. He, too,developed a special interest in stroke.He participated in multicenter studieson TIA and was a strong contributor tothe residency teaching program beforemoving to the Group Health system in1982.The Seattle Veterans Hospital. Thishospital was constructed in 1951.Henry Leffman, an Army neurologiststationed at Fort Lewis near Tacomabecame the VA neurologist andremained there until his retirementin 1969. Dr. Leffman was a wonderfulteacher of residents and students,though he saw only a limited numberof the neurology inpatients and therewere no outpatient clinics there until1972. Dr. Leffman was said to have readevery article in the journal Brain. Hedid little research, but made importantcontributions to studies on periodiclateralized epileptiform discharges(PLEDs), and other clinical studies.Pediatric neurology. In the 1950s andearly 60s, the Department of Pediatricsmaintained inpatient and outpatientservices at the University Hospital.Children’s Hospital was affiliated.Dr. John T. Chapman was trained inPediatric Neurology and was employedby Children’s Hospital until he left forprivate practice in 1970. In 1964, whenAugust Swanson became Head of theDivision of Neurology, he recruitedColdevin Carlson to head PediatricNeurology. Dr. Carlson was initiallybased at the University Hospital, butwhen it became clear that there wasgreater potential for pediatric neurologyat Children’s, Dr. Carlson moved there.A pediatric neurology clinic continuedat the University Hospital, with DonFarrell and I attending.Clinical neurophysiology and epilepsy.Dr. Gian-Emilio Chatrian became theDirector of EEG. Dr. Chatrian wastrained in neurology in Italy, and cameto Seattle from the Mayo Clinic. Dr.Chatrian developed an outstandinglaboratory, and taught all neurologyresidents, who rotated usually for threemonths. In 1969, when the School ofMedicine combined UWMC and HMClaboratories into a new Departmentof Laboratory Medicine, Dr. Chatrianchose that department for his primaryacademic appointment. He trained Dr.Continued on page 85

Update from the Division of Pediatric NeurologyBy Russell Saneto, PhD, DOActing Division Head of Pediatric NeurologyThe coolness of fall reminds us of thechanging of seasons. Part of our livesrevolves around changes, and withinour group, there have been somesignificant changes. Dr. Sid Gospe hasstepped down as Division Head, as ofMarch 1, 2017. We will miss Sid greatly.He expanded child neurology fromfour to over 22 members. The childneurology residents increased from oneto three per year. We have become oneof the premier programs in the nationunder Sid’s leadership. For all that youhave done Sid, thank you. Sid will nowbecome a doting grandfather to his firstgrandson in North Carolina. Soon, hisdaughter Jessica will give the Gospes asecond round of grandchildren: Jessicais pregnant with twins.The coming of spring gives us theanticipation of new potential growth.We welcome our second class of threeresidents who have entered theirpediatrics years. This outstandinggroup of new interns are: AngadKochar, MD; Laurel Persa, MD; andBrittany Sp

, the UW Department of Neurology’s newsletter for colleagues, alumni and friends. I am proud to share the latest exciting developments in our department, including news on research, clinical resources, and education. In this issue we spotlight the UW Headache Clinic, the only academic headache center . in the WWAMI region, and a unique