Transcription

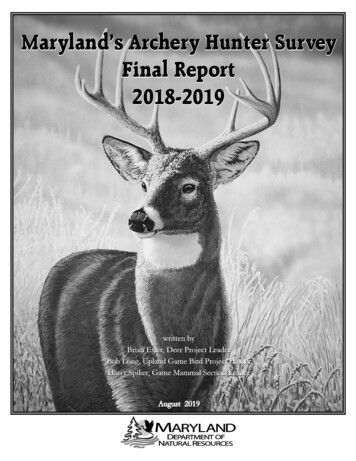

Larry Hogan, GovernorJeannie Haddaway-Riccio, SecretaryHarry SpikerGame and Mammal Section Leader301-334-4255Wildlife & Heritage Service580 Taylor Ave, E-1Annapolis, MD 21401Toll free in Maryland: 877-620-8367Out of state call: 410-260-8540TTY Users call via the MD Relay 711dnr.maryland.gov/wildlifeThe facilities of the Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion,sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin, or physical or mental disability.This document is available in alternative format upon request from a qualified individual with disability.This program receives federal assistance from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and thus prohibits discrimination onthe basis of race, color, national origin, disability, age, and sex in educational programs, pursuant to Title VI of the CivilRights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of1990, the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, and Title IX of the Educational Amendments of 1972. If you believe thatyou have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or service, please contact the Office of Fair Practices-MDDepartment of Natural Resources, Tawes Building, 580 Taylor Ave., D-4, Annapolis, MD, 21401. The telephone numberis 410-260- 8058. You may also write to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Policy and Programs, Wildlife andSport Fish Restoration Program, 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Mail Stop: WSFR-4020, Arlington, Virginia 22203.Survey and inventory results reported in thispublication were funded by theFederal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act.8/2019 DNR 03-080519-161

Dear Sportspersons,The attached report summarizes the Archery Hunter Survey data for the 2009-10 through2018-19 archery seasons. I hope that you will take a chance to read the report and participate infuture surveys. Your participation is critical as we continue to monitor Maryland’s diverse wildliferesources.I would like to personally thank each and every individual who took the time to fill out and return the Archery Hunter Survey form. Your efforts will contribute greatly to our overall knowledgeand conservation of Maryland’s wildlife resources. If you have not, or do not receive a survey, butare interested in participating, the form can be accessed online.Respectfully,Harry SpikerGame Mammal Section Leader1

IntroductionAquatic species, nocturnal species and species thatutilize inaccessible areas or habitat types that hunters donot frequent, will normally have a lower probability ofbeing observed than do other species.Archery hunters annually spend a large number of daysin the field and tend to be quite observant while onstand. These two traits enable these individuals to beideal participants in structured observational surveys likethe Archery Hunter Survey.Although vulnerability to observation varies among species, it remains consistent for individual species duringsuccessive years. For example, some species, such as beaIn an effort to gain insight into furbearer and other wild- ver, have a low probability of being observed. However,that probability remains the same from year to year. Aslife populations across Maryland, the Archery HunterSurvey was established in 2002 and has been conducted a result, you can still detect beaver population changesover a period of years.annually since. During the 2018-19 survey period, morethan 300 cooperative archery hunters from across theThe inherent value of this type of survey is to accustate returned survey forms that were used to conductrately track wildlife population trends through time on athe assessments in this report.statewide scale. It is important to note that data from anumber of successive years is necessary before you canSurvey participants were asked to complete the surveyforms and record any observations of wildlife while they begin to accurately assess these trends. With the 2018-19season marking the17th year that the survey has beenwere archery hunting. They were also asked a myriadcompleted, observation trends for certain species haveof other questions, including number of hours hunted,county hunted, if the hunt occurred on public or private developed nicely. As the body of data from this surveycontinues to increase in future years, the results will supland and if bait, cover scent, an elevated stand or lureply one of the cornerstones for the conservation andwas used.management of many of Maryland’s wildlife species.Survey participants recorded information at the countylevel. Counties were then split into their respective physiographic provinces (Figure 1). In some instances, it was Furbearersnecessary to include a county in only one physiographic By Harry Spikerprovince despite two provinces occurring in that countyAll of Maryland’s 14 species of furbearers were ob(ex. Frederick and Cecil).served by Archery Hunter Survey participants this year.Although regional observations for some species variedFor this survey, the Appalachian Plateau Province consisted of Garrett County. The Ridge and Valley Province between individual survey periods, statewide observationrates remained relatively consistent (Table 1, Figures 2included Allegany, Frederick and Washington counties.and 3).The Piedmont Province was comprised of Baltimore,Carroll, Cecil, Harford, Howard and Montgomery counRed fox continued to be the most frequently observedties. The Western Coastal Plain Province consisted offurbearer during the 2018-19 hunting season by a wideAnne Arundel, Calvert, Charles, Prince George’s andmargin. The greatest number of red fox sightings ocSt. Mary’s counties. The Eastern Coastal Plain Provincecurred in the Piedmont Province. Red fox observationsincluded Caroline, Dorchester, Kent, Queen Anne’s,did not fluctuate significantly between the 2009-10 andSomerset, Talbot, Wicomico and Worcester counties.2018-19 survey periods in any region of the state withthe exception of the Appalachian Plateau Province.The resulting data was then tabulated and reduced to(Table 1, Figures 4 and 5).a standard unit of measurement (observations per 100hours of hunting). This standard unit of measurementwas then used to analyze a number of different variables Gray fox observations remained fairly steady in all provinces during the 2018-19 survey period (Table 1, Figure 5).(e.g. elevated stand, lure, month, region, etc.). Standarderrors (SE), where provided, were calculated using ratioCoyotes are found statewide and were once again reestimates and provided a measure of variability in theported in each of the physiographic provinces duringresults.the 2018-19 survey period with the highest observationrates occurring on the Appalachian Plateau (Table 1,It should be noted that different species have varyingFigures 4, 5 and 6).susceptibility to surveillance. Therefore, variations inobservation rates between different species may not bean accurate reflection of comparative densities.2

Bobcat numbers have historically been centered in theAppalachian Plateau and Ridge and Valley Provinces.That trend continued during the 2018-19 season withobservations of this elusive furbearer limited once againto these two provinces (Table 1, Figure 7).tailed does, 25.4 white-tailed fawns and 10.1 unknownwhite-tailed per 100 hours of archery hunting (Table 1).For 2018-19, the average hunter who participated in thesurvey spent a total of 52.9 hours archery hunting withan average hunt length of 3.6 hours.Raccoons were observed statewide with the greatestconcentration occurring in the Piedmont Province.During the 2018-19 archery season, striped skunks wereobserved in all provinces except the Piedmont Provincewhile opossums occurred in all of the provinces (Table1, Figures 7 and 8). Small, elusive and often undetected,weasels were only reported in the Ridge and ValleyProvince during the 2018-19 survey period (Table 1).The number of white-tailed deer observed by archeryhunters remains relatively stable across the state. Archery hunters in 2018-19 statistically observed the samenumber of bucks, does and fawns as they did in 201718. Yearly fluctuations in deer observations are often related to the amount of natural forage and mast availableduring the hunting season. When more natural forageand mast is available, deer do not have to move as muchseeking food and, therefore, are not observed as oftenby hunters. They also do not respond to bait like theydo when mast is limited. Likewise, warm weather, whichhas been prominent during recent hunting seasons, alsoalters deer movements and can reduce sightings andharvests.Aquatic furbearer (beaver, mink, muskrat, nutria andotter) observation rates are typically lower than manyof the terrestrial furbearer species due to the nature ofarchery hunting and the type of habitat where theseanimals spend their time. During the 2018-19 huntingseason, mink were reported in the Appalachian Plateau,Ridge and Valley, Piedmont and Eastern Coastal provinces. Muskrat were reported in the Ridge and Valleyand Eastern Coastal Provinces and beaver were observed within the Piedmont and both coastal provinces(Table 1, Figures 9 and 10).Geographic Province ResultsArchers in 2018-19 observed a high mean of 28.0 whitetailed bucks per 100 hours in the Appalachian PlateauProvince and a low mean of 13.5 bucks per 100 hoursin the Western Coastal Plain Province (Table 1). Archery hunters reported the most white-tailed does per100 hours (58.8) in the Appalachian Plateau Provinceand the fewest white-tailed does per 100 hours (26.0) inthe Western Coastal Plain Province. Fawn observationsranged from a high mean of 46.6 in the AppalachianPlateau Province to a low mean of 14.9 in the Western Coastal Plain Province. The number of unknownwhite-tails observed per 100 hours ranged from a highmean of 15.1 in the Appalachian Plateau Province to alow mean of 5.9 in the Eastern Coastal Plain Province(Table 1).Rabbits and SquirrelsBy Harry SpikerCottontail rabbits and all three harvestable species ofsquirrel (eastern fox, gray and red) were observed duringthe 2018-19 survey period (Table 1, Figure 12 and 13).Gray squirrels were by far the most commonly observedspecies and appeared in every province. The eastern foxsquirrel was observed in all provinces except the Western Coastal and red squirrels were encountered in theAppalachian Plateau and Piedmont provinces during the2018-19 season. Archery hunters observed 66 Delmarvafox squirrels, a non-game species unique to Maryland’sEastern Coastal Province (Table 8). Cottontail rabbitswere once again observed statewide during the samplingperiod (Table 1, Figures 13 and 14).Archers in the Western Coastal Plain Province spentthe most time archery hunting in 2018-19 (65.3 hours/hunter), whereas archers in the Ridge and Valley Province spent the least amount of time archery hunting(35.9 hours/hunter). Average hunt length ranged from4.1 hours/hunt in the Eastern Coastal Plain Province to3.3 hours/hunt in the Piedmont Province (Table 1).White-tailed DeerBy Brian EylerRegional deer observation data collected by archeryhunters during 2018-19 suggest that the deer populationin Maryland has been relatively stable (Fig. 15). Yearlyfluctuations within regions can be attributed to deerpopulation changes, availability of mast and individualhunter effort and skill of those completing the surveys(Fig. 16). Observation rates were statistically similar forthe regions when compared to 2017-18.Archery hunters observed 3,298 white-tailed bucks,6,847 white-tailed does, 4,051 white-tailed fawns and1,602 white-tailed of unknown sex and age (15,798 total) statewide during a reported 15,921 hours of archeryhunting during the 2018-19 season. Archers statewideobserved a mean of 20.7 white-tailed bucks, 43.0 white3

which has the added negative effect of encouraging deerto increase their nocturnal movements and minimizetheir movements during legal hunting hours.Measures of standard error presented in the data tablesprovide additional insight into statewide and regionalobservation differences. Small differences in standarderror indicate most hunters in the region are observingsimilar numbers of deer. Larger differences in standarderror suggest that some hunters are observing manymore deer per hour than other hunters in the region.Differences can be attributed to public land vs. privateland hunting, varying degrees of management for deerand hunter effort.Elevated Stand UseElevated stands (trees, ladders, tripods, etc.) continue tooffer an advantage in many instances for observing deer.Archers in 2018-19 observed 21.9 bucks per 100 hoursfrom elevated stands, compared to 14.5 bucks per 100hours when ground hunting (Table 3). Archers observed43.9 does per 100 hours from elevated stands vs. 37.9per 100 hours from the ground (not significantly different). Elevated stands, in most cases, enable huntersto see further distances and remain undetected longercompared to hunting on the ground.Lures, Cover Scents and BaitLike previous years, archery hunters observed similarnumbers of bucks in 2018-19, regardless of whetheror not they were using lures to attract deer (Table 2).Archers observed 18.9 bucks per 100 hours when usinglures, compared to 21.2 bucks per 100 hours when notusing lures. Statistically, there was no difference in theseobservation rates. Similarly, archers observed 34.6 doesper 100 hours when using lures, compared to 45.0 doesper 100 hours when not using lures (statistically no difference).Deer hunters are strongly encouraged to wear a full bodysafety harness while in a stand and to use a fall restraintsystem while climbing, entering and exiting the stand. Additional information on tree stand safety is available athttp://dnr.maryland.gov/huntersguide/bb ts.asp.Monthly ResultsThe use of cover scent in 2018-19 also did not appearto change how many bucks or does archers observedstatistically. Archers observed 19.1 bucks per 100 hourswhen using cover scent, compared

Archery hunters annually spend a large number of days in the field and tend to be quite observant while on-stand. These two traits enable these individuals to be ideal participants in structured observational surveys like the Archery Hunter Survey. In an effort to gain insight into furbearer and other wild-life populations across Maryland, the Archery Hunter Survey was established in 2002 and .