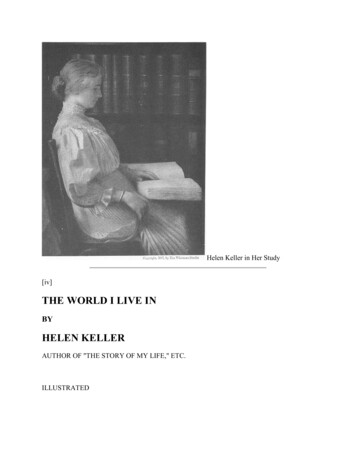

Transcription

HELEN’S DIVINE ORIGINSLowell Edmunds, Rutgers University, USAlowedmunds@gmail.comIt is generally agreed that she must havebeen a goddess before she was a mortalheroine, but the connection betweenthese two incarnations is obscure.Andrew L. Brown 1996: 675It often happens that an article follows up loose ends in anotherarticle, one's own or someone else's. This article is a case in point,returning rather shame-facedly to a too brief discussion of Helen's originsin an article published several years ago.1 I was trying to make a critiqueof the consensus expressed in the epigraph on this page, that Helen was “agoddess before she was a mortal heroine.” Such a goddess wouldconstitute a determinate origin of Helen's myth and her cults. Startingfrom a goddess origin, one would only have to explain, in order to explainthe myth, how the goddess became the mortal heroine. “But theconnection between these two incarnations is obscure.” Not only is theconnection obscure, but more than one goddess is in question and morethan one kind of goddess. Indo-European mythology offers a candidate orcandidates; Greek cult seems to offer another. One has to pick and chooseamong origins, if an origin is what one wants. Having offered critiques ofthe Indo-European and the cultic origins of Helen that scholars have1Edmunds 2002-2003.

2 Electronic Antiquity 10.2proposed, I address, in the final part of this article, the question whyscholars wanted and continue to want origins.1. Indo-European prototypes of HelenMost modern scholars see ancient andprehistoric European culture not as theexclusive product of a mythical IndoEuropean tribe, but as the result ofmulti-cultural activity along land andsea trade routes (which, coincidentally,cover much the same region as the IndoEuropean descendants, but without thehole in the Middle East).Christine Goldberg 1998: 251 n. 7Dragons are by no means confined tothe Indo-European world, needless tosay, but it is possible to employlinguistic methods to determine some ofthe characteristics of specifically IndoEuropean monsters .Joshua T. Katz 2005: 28.Cognates of Helen have been perceived in the mythologies of three otherpeoples speaking languages in the Indo-European family: the IndianSuryâ, the daughter of the Sun in the Rig Veda, the Lithuanian Saulêsdukterys, and the Latvian Saules meita, in each case “Sun’s daughter.”2As Helen has twin brothers, the Dioscuri, who are associated with horsesand are saviors, Suryâ has twin brothers, the Ashvins, who have more orless the same attributes as the Dioscuri.3 The Lithuanian and Latviandaughters also have twin brothers, the Dievo sunêliai and the Dieva dêli.The latter rescue their sister.4 In one of the Latvian folk songs which arethe source for these twins and their doings,2Suryâ is the feminine form of Surya, “Sun.” For a survey of the evidence seeFrame 1978: 139-40.3The situation is complex, however. See Güntert 1924: 260-76; Nagy 1973: 172n. 94; Frame 1978: 139-40.4Ward 1968: 64-66; Puhvel 1987: 228-29.

Edmunds Helen’s Divine Origins 3Saule’s daughter waded in the sea,they saw only her crown.Row the boat, sons of Dievs,save Saule’s [ of Saules meita] soul!5In addition, Helen’s father is Zeus, the Ashvins’ father has the cognatename Dyaus, and the name of the Latvian twins’ father, Dievs, is anothercognate. Helen and the Dioscuri are, M.L. West concluded, a “nugget ofIndo-European mythology, preserved from a time long before theHellenes came to Greece.”6Further comparison of the Dioscuri with the Ashvins, however,has proven to be difficult. While the latter are gods of dawn, and have anepithet which can be interpreted to mean “bringing back to light andlife,”7 their so-called “rescue” of their sister is a matter of their role in thesetting and the rising of the sun. Compare the Latvian song just quoted.Vedic myth does not offer any story about the Ashvins and Suryâ thatcorresponds with the Dioscuri’s rescue of their sister when she wasabducted by Theseus and Peirithoüs. (The Dioscuri play no role in theTrojan War myth.) Indeed, the relations between the Ashvins and Suryâin the Rig Veda are extremely various.8 As for the Vedic Dyaus, he is notthe personified sky-god that Zeus is but simply the sky.9As Stephanie Jamison has remarked, “given its enigmatic style,the Rig Veda has very little direct evidence for anything.”10 But the mainreason for the absence of an abduction story in the mine from which the“nugget” came is that the marriage of Suryâ is of the svayamvara type, inwhich the maiden chooses for herself.11 The Ashvins, whatever their role,presumably cooperate. Suryâ could thus be considered in fact the antitype of Helen. (Even if Helen leaves Sparta with Paris willingly, she isnot, by this act, choosing him as a husband. She is deserting the husbandshe already has.)The most promising narrative parallel between Vedic myth andthe Greek myth of Helen was pointed out by Vittore Pisani. In 1928, he5Puhvel 1987: 228.West 1975: 8. For a good summary of the parallelisms, including the Latvianone, see Macdonell 1897: 53; Skutsch 1987: 189.7Frame 1978: 134-40.8See Macdonell 1897: 51.9Macdonell 1897: 21-22.10Jamison 2001: 303. Her emphasis. Cf. Thomson 2004.11Jamison 2001: 304-309.6

4 Electronic Antiquity 10.2published an article in which he compared Saranyu (probably anotherdawn goddess) with Helen with respect to one of the most problematicalaspects of her myth, the image that went to Troy with Paris while the realHelen stayed in Egypt.12 Saranyu disappears at the time of her weddingto Vivasvant and the gods replace her with an image (RV 10.17.1-2), i.e.,the husband here gets the image, whereas in the Greek myth the abductorgets it. Of the two stanzas in question, the second is more difficult. Itappears to mean that, before she disappears, she gives birth to andimmediately abandons the Ashvins.13 In the Vedic myth, then, thewoman replaced by an image is the mother of the twins, while in theGreek myth, she is their sister.An Indo-European prototype has been proposed for Paris, too.Deborah Boedeker, in Aphrodite’s Entry into Greek Epic, exploresepithets and narrative functions common to Aphrodite, Eos, and theVedic dawn goddess Ushas. Aphrodite’s rescue of Paris in Iliad 3, shefinds, belongs to a particular type of abduction-preservation narrativeearlier defined by Gregory Nagy: a goddess (Eos or Aphrodite in Greekmyth) falls in love with a beautiful young man, whom she abducts andupon whom she confers immortality.14 Nagy’s prime case in Greek mythwas the story of Eos and Tithonus.15 Boedeker finds that, in theabduction-preservation of Paris, too, which culminates in the union ofParis and Helen, the erotic impulse of the abducting goddess is latent.16The work of Linda Clader supported Boedeker’s finding. Concentratingon the two women in the triangle Paris-Aphrodite-Helen, and beginningfrom Helen’s epithets in Homer, Clader came to a conclusion that tendedto confirm Helen’s typological affinity with Aphrodite and the dawngoddess figure.17 About a decade after the time of the studies just12[1928]1969: 323-45. Skutsch 1987: 190 says that the connection of Helenwith Saranyu was first pointed out by J. Ehni in 1890 but does not give areference. For discussion, see Grotanelli 1986: 127-30. For Saranyu as dawngoddess, see Macdonell 1897: 125. Doniger 1999: 41-55, speaking of Saranyuas “the key to the relationship between Sita and Helen,” provides extensivediscussion of the history and variants of the Saranyu myth.13Pisani [1928]1969: 338. For instantaneous pregnancy and parturition, comparethe alien woman played by Natasha Henstridge in the American science fictionmovies “Species” (1995) and “Species 2” (1998).14Nagy 1973.15A story much on the minds of classicists because of the “new Sappho.”16Boedeker 1974: 40, 61-62.17Clader 1976: 53-62.

Edmunds Helen’s Divine Origins 5mentioned, Ann Suter revisited Aphrodite’s rescue of Paris,concentrating now on Paris and reinforcing Boedeker’s perception of themyth of the dawn goddess as underlying the narrative of Iliad 3. Paris,Suter concluded, is “the analogue for the Dawn goddess’ consort.”18The Rig Veda offers, then, three possible cognates of Helen:Suryâ, Saranyu, and Ushas. Because all three are dawn goddesses, theIndo-European comparatist will look for solar attributes of Helen. Forexample (and probably it is the best example), she once has the epithetDios thugatêr (Od. 4.227), which is the exact cognate of Ushas’ epithet,divás duhitár.19 But the non-solar virgins Artemis and Athena have thisepithet, too, the former once (Od. 20.61), the latter several times (Il.2.548, 4.128, etc.). The Greek epithet has obviously been loosed fromany solar moorings it might once have had. Helen is even compared toArtemis.20 As already indicated, the supposed resemblance of Helen’sbrothers, the Dioscuri, to the Ashvins does not produce a strongargument for her descent from the dawn goddess, and another pair oftwins in Sanskrit literature have presented themselves as more likelycognates.21The closest parallel to the Trojan War myth in Sanskrit literatureremains the abduction of Sita, which is the central story of Valmiki’sRamayana, and the next-closest is the abduction of Draupadi in theMahabarata (3.248-83). In fact, the hermit Markandeya tells the story ofRama and Sita to one of Draupadi’s husbands, who believes that he is themost unfortunate of men, in order to console him (MBh 3.257-276.1).The parallelism between Helen and Sita extends, in later versions of thestory, even to the creation of a double of Sita, who has the sameexculpatory function as the image which went to Troy in place of the realHelen. In one of these versions, the double of Sita in her thirdreincarnation becomes Draupadi. Though the earliest sources for the18Suter 1987: 56.Schmitt 1967: 169-73; Nagy 1973: 162.20Od. 4.122. The line became the basis of the Pythagoreans’ rehabilitation ofHelen, who, they said, came from the moon (because Artemis was the moon)and returned there after the plan of Zeus was accomplished through her. SeeDetienne 1957.21The sons of the Ashvins, the twins Nakula and Sahadeva, two of the Pandavasand thus two of the husbands of Draupadi, in the Mahabarata, have been seen asparallel to Agamemnon and Menelaus: Wikander 1957: 66-96; Clader 1976: 5053. For a rethinking of Wikander, see Frame 1978: 143-52, who demonstrates aparallelism between Nakula and Sahadeva and the Vedic twins.19

6 Electronic Antiquity 10.2abduction of an image of Sita come from the fifteenth century C.E.,images of Sita serving other purposes are found already in Valmiki, andthus a capacity for doubling already belongs to this character.22By the same kind of reasoning which infers a particular IndoEuropean “nugget” from cognate names in the Rig Veda, in Greek,Latvian, and Lithuanian myth, one could infer an Indo-European“Abduction of the Beautiful Wife” from the story-pattern common to theRamayana, the abduction of Draupadi in the Mahabarata, the TrojanWar myth, and the Old Irish antecedents of the Guinevere story.Furthermore, as Jamison has shown, the parallels between a scene inHomer’s Iliad (the Teichoscopia in 3.161-244) and one in theMahabarata are so close that a prototype in Indo-European epic can beassumed.23 She discusses abduction (Rakshasa marriage) as one of eighttypes of legal union in Sanskrit law codes; shows how, in this context,the abduction of Draupadi is illegal; how her recovery is a “reabduction,” meeting the legal conditions of this kind of marriage; andhow the narrative of Iliad 3 can be understood as a Greek version of partsof this kind of “re-abduction.”24 The parallelism is so close that the “reabduction” takes place only after Draupadi ( Helen) replies toquestioning by her abductor, King Jayadratha ( Priam, instead of Paris),concerning her five Pandava brothers, her rescuers ( Menelaus and theGreeks). She has to identify each of them by name.25One of the features of the Indo-European “Abduction of theBeautiful Wife” would have been the double nature of the abductor,human and superhuman. The abductor of Sita is the demon king Ravana.He carries her away in the Pushpaka Vimana, an airborne chariot.Despite the fact that he is a demon and a master of such devices as thischariot, he can be slain, and finally Sita’s husband, Rama, slays him. Thesuperhuman side of the abductor is prominent in the Celtic prototype ofthe medieval romance about Lancelot and Guinevere, as reconstructed by22Ramayana 6.68.1-28; 7.89.4. For discussion of the illusory Sita, see Doniger1999: 12-23, 27-28.23Jamison 1994: 5-16. For the evidence for Indo-European epic, see Katz 2005.24For an extensive discussion of “marriage by capture,” see Jamison 1996: 21835. Allen 2002 argues for a pentadic structure common to the Trojan (includingepisodes in Epic Cycle) and Kurukshetra Wars (MBh), with many commonthemes, e.g. "Ambiguous female (Athena, Sikhandin) collaborates in killing,""Mutual affection between enemies (Achilles and Priam, Arjuna and Bhishma)."25Cf. summary and discussion by Katz 2005: 27-28.

Edmunds Helen’s Divine Origins 7T. P. Cross and W. A. Nitze. He lives in a supernatural realm, fromwhich the wronged husband is nevertheless ultimately able to recover hiswife. As for the abductor of Helen, he has two names. One, Alexanderbelongs to Trojan tradition, indeed to Trojan history.26 The other, lesscommon name is Paris. Suter has studied this pair of names in relation toeight other pairs of names in the Iliad and has shown that ParisAlexander “conforms to the demands of the [Iliadic] convention of‘language of gods and language of men’. Further, she has shown that"the introduction of Paris [in Book 3], the marked divine name, and thenarrative pattern of the episode which follows the introduction, conformto the pattern established by names explicitly designated as divine, andParis, when used thereafter, indicates connections of the character withthe divine.”27 Though the divine side of Paris is certainly in thebackground in the Iliad, his two names point to an ambiguity that linkshim to Ravana and to the Celtic abductor.To return to Jamison’s account of Helen’s naming of the Greekheroes in Book 3 of the Iliad, it is worth pausing to notice how the Greekepic tradition has specialized the figure of Helen and has given aparticular significance to the naming. Richard Martin has shown that thispassage, even though it is not ostensibly a lament, contains the strategiesand diction of the lament genre, and belongs to a consistentcharacterization of Helen as keening woman. He supports his finding bycomparison with lament as practiced by the women of Inner Mani inGreece. He concludes: “Helen is so closely associated with lament inGreek tradition that she becomes its metonym.”28 As lament is thefoundational speech act of all poetry of commemoration, and Trojan Warepic commemorates the heroes by preserving their kleos, so Helenfigures the particular poetic tradition in which, at the narrative level, sheis the cause of the action. This specialization of Helen amounts, then, to aself-consciousness on the part of Homeric epic concerning its narrativeraison d’être, which one could call the myth of Helen. This myth is thenotional whole to which every performance looks.29 The Hesiodictradition is consistent with the Homeric one. The Catalogue of Womenculminates in the marriage of Helen and Menelaus, which marked the26Treaty between Alaksandu of Wilusa and the Hittite king Muwattalli II (ca.1290-1272 B.C.E.): see most recently Latacz 2004: 105-110.27Suter 1991: 25. For earlier discussion of pairs of names in Homer see 13 nn.1-2.28Martin 2003: 128.29For the notional whole, see Nagy [1979]1999: xvii and 2003: 14-15.

8 Electronic Antiquity 10.2beginning of the end of the age of heroes. Concluding the catalogue ofher suitors, Hesiod immediately reports Zeus’ plan to obliterate the raceof men and the heroes in particular (fr. 204.96-101 M-W). The TrojanWar, to be caused by Helen, is his means to this end (cf. Cypria fr. 1Bernabé).30 Martin's interpretation of the naming complements theinterpretation of Helen's weaving, also in Book 3 (125-28), as a figure ofpoetic composition.31To conclude on Sanskrit epic, viewed in a broader context, itseems to point to an Indo-European prototype different from the onediscerned in the Rig Veda. In the former, a woman is abducted from herhusband. He goes to the land of the abductor, kills him, and recovers hiswife. In the latter, the woman is a dawn goddess and is associated withtwins. The main (the only?) story about her concerns a mortal lover. Itmight, however, be wondered if these two prototypes are in fact two anddistinct or if they can somehow be connected. Wendy Doniger hasproposed a point of connection. Having discussed the similarity of Helento Sita, especially with respect to the double of Sita in Tulsi (15thcentury C.E.) and in other later sources, she goes on to propose thatSaranyu (“or the subject of another, now lost story on which Saranyuherself was modeled”32) might have served as a model for both Sita andHelen. She argues for this model with reference to features which linkSaranyu, Sita and Helen—a connection with the sun; a relation to twins;a double.As for a solar Helen, much doubt is necessary, as I havesuggested, and, as for Sita, her name means “Furrow.” Doniger herselfconcedes that the case for a solar Sita is weak. With twins, one is onfirmer ground. Both Saranyu and Sita bears twins, Sita, however, afterthe time of her rescue. Helen is the sister of twins. One would not wantto deny that the Dioscuri are an Indo-European reflex in the myth ofHelen, though enthusiasts for this particular reflex have again and againbeen led by the Dioscuri’s explicit rescue of their sister to read “rescues”back into the quite different relations between the other twins and their30Cf. West 1985: 43, 50, 114-15, 119-21.For a bibliography of this interpretation see Pantelia 2002: 25 n. 21. Helen,when she first appears in the Il., is weaving a large purple cloth into which sheworks many scenes of the trials which Trojans and Achaeans suffered on heraccount. Kennedy 1986 shows the ways in which Helen cannot serve as thefigure of the bard, with particular reference to the Teichoscopia and the gaps inher knowledge which emerge in that scene.32Doniger 1999: 60.31

Edmunds Helen’s Divine Origins 9sister. The episode in Helen’s life in which the Dioscuri play a role, i.e.,her abduction by Theseus, is a distinct kind of story, typologicallydifferent from the abduction by Paris.33 These two abduction stories areindependent, as is the story about the egg from which Helen was born.Homer draws a line between the two abduction stories when he says ofthe Dioscuri, “Already the life-bearing earth possessed them inLacedaemon, in their own native land” (Il. 3.243-44). The Dioscuribelong to neither the temporal nor the geographical framework of theIliad.A double is also something which Saranyu, Sita and Helen havein common, provided that the late sources for Sita’s are relevant. As forSaranyu’s double, in the Rig Veda, it is an image which is left to consoleher husband. The shadow of Sita, however, is for the purpose of deludingRavana and preserving her chastity. Doniger adduces a story about adouble or doubles of Saranyu (here Samjna) from the Harivamsha(perhaps 600 C.E.), but this story is typologically quite different from theabduction stories in which the doubles of Sita and Helen play a role.Doniger’s relentless (and hardly unproductive) concentration on thedouble causes her to construct a comparative circle admitting evidencethat could not be admitted into mine, which is driven by the conjunctionof the abduction and rescue motifs. For the double of Saranyu, I amafraid that the somewhat obscure evidence of the Rig Veda, presentedabove, is all that is available. It does not look like a parallel to the doublein the abduction stories.One is left with twins as the only feature securely linkingSaranyu, Sita and Helen, and, as noted, the narrative function of thetwins differs considerably from one source to another. If one setstypological narrative consistency as the standard (as distinguished fromthe principle that Lewis Richard Farnell called noscitur a sociis), then thevarious twins turn out to be rather weak links.34 Although I am, with thisconclusion, opposing Doniger, I am doing so in her spirit, in that I amoffering, on the basis of a differently motivated comparative circle,“another, now lost story,”35 i.e., the Indo-European abduction story,33Edmunds 2002-2003: 20.Farnell 1921: 199-200. He defines this principle as: "the significance of aperson may be revealed by the significance of his associates." My doubts aboutthe comparative value of the Vedic and other twins are hardly original with mebut are already well articulated in Farnell's chapter on the Dioscuri (175-228).35Doniger 1999: 60.34

10 Electronic Antiquity 10.2which I believe is the prototype for the stories of Helen and Sita.Whether or not also of Saranyu, I am unsure.It remains to explain the relation of the folktale, “The Abductionof the Beautiful Wife,” discussed in my earlier article on Helen, to theIndo-European prototype for the myth of Helen.36 I spoke of the folktaleas defining the conditions of possibility of the Greek myth, and Iassumed contact between folktale and myth within a specifically Greek(though indeterminable) history. But if I posit an “Abduction of theBeautiful Wife” already in Indo-European myth and indeed in IndoEuropean epic, where does the folktale come in? I would say that thefolktale must define the conditions of possibility for the Indo-Europeanprototype, too, in addition to whatever influence it exercised later withina specifically Greek reception. Whether it was also an Indo-Europeanfolktale or came into the Indo-European domain through borrowing isimpossible to say.The historical precedence of folktale to Indo-European prototypetakes further back in time a process of integration that is well attested forGreek hero myths or legends, many of which display more or less thesame plots as international folktales. In his explanation of thisphenomenon, William Hansen begins by asking:Do the Greek hero legends derive from old, internationalfolktales? Or have the old hero legends turned into thefolktales of today, as the theory of devolution has it?He answers:Close comparison of ancient and modern variants of thesame story leads me regularly to the conclusion that when aGreek legend and an international folktale share a similarplot, the legend derives from the folktale rather than theother way around, for it is almost invariably easier tounderstand how an individual Greek legend might havedeveloped as a special adaptation of a more general storythan to understand how the folktale might have developed36Edmunds 2002-2003.

Edmunds Helen’s Divine Origins 11from the particularized and highly adapted story that alegend is.37This same reasoning I would apply to the historical relation of“Abduction of the Beautiful Wife” to the Indo-European story-patterncommon to the Ramayana, etc. The Indo-European "Helen" occupies thesame position as the Indo-European dragon in the epigraph from JoshuaKatz, and, as in the epigraph from Christine Goldberg, one tends to thinkof her not as an Indo-European creation, certainly not in W.R. Halliday'ssense, but as a multi-cultural product.38As for the early date which my account presupposes for thisinternational story, there is of course no direct evidence, and one finalcomparison may help, this time with the better-documented ancient NearEast. The folklorist Heda Jason states: “As for literate cultures, themaximal depth reached is four and a half millennia of writtendocumentation in the ancient Near East. This documentation does notshow any change in the qualities of the genres, down to details of taletypes. Already the earliest specimens preserved show exactly the sameliterary qualities of form and content as modern oral tradition.”392. Greek cults of HelenOf the various cults of Helen in ancient Greece, one in or nearSparta and one on Rhodes have had the most importance for the mythritual interpretation of the origin of her myth, i.e., the interpretationaccording to which a ritual generated the myth.40 In these cults, Helen is37Hansen 2002: 15-16. Cf. West 1985: 30: “Much of the legendary matter whichthe poet [of the Hesiodic Catalogue of Women] incorporated must have come tohim in epic guise; some of it was pure folk-tale, but we can see from theOdyssey that such material was readily drawn into the ambit of epic poetry,indeed may have existed in no other poetic form.”38Halliday 1933: 13, for example: "If the fairy stories of the world areconsidered, it can hardly be questioned that the Indo-European märchen fall intoa single group. In general character they are recognizably different from thetales of the Lower Culture in other parts of the world. Indeed, it is noticeablehow rapidly Indo-European stories become distorted where they have beendiffused outside the main area to which they belong. This may be observed, forexample, in the variants which have been thrown off southwards along the lineof Arabic influence in Africa, e.g. in Zanzibar or among the Ba Ronga."392000: 35. Cf. Burkert 1992: 120-24 on the animal fable.40In arguing against this interpretation I am not presupposing that myth-ritualinterpretations are always wrong. Cf. the balanced account of Bremmer 1994:

12 Electronic Antiquity 10.2associated with trees, and thus she comes to be interpreted as a fertilitygoddess who somehow turns into a figure in myth (cf. the epigraph fromAndrew L. Brown with which this article began). On Rhodes, there wasan apparently related sanctuary of Helen Dendritis, “Helen of theTree.”41 At Sparta, Helen had a sanctuary (hieron) at Platanistas, “Planetree Grove.”42 This place lay in Pitanê, the most famous quarter ofSparta, where Pausanias saw twenty temples, eleven hero shrines, fivegraves, and five statues, amongst other things.43 Helen was, then, hardlythe only object of cult in this quarter, though, when she is discussed apartfrom the rest of the landscape, her unique prominence tends to beassumed.a. Platanistas and RhodesTheocritus is the source for a plane-tree and its ritual,44 in honorof Helen, plausibly assumed to have taken place in the sanctuary atPlane-tree Grove (Id. 18.43-48). He conjures up the epithalamion sungby young women of Sparta at the marriage of Helen and Menelaus. Thelines suggesting the cult, otherwise unknown, run:We first a crown of low-growing lotus45having woven will place it on a shady plane-tree.First from a silver oil-flask soft oildrawing we will let it drip beneath the shady plane-tree.Letters will be carved in the bark, so that someone passing bymay read in Doric: “Reverence me. I am Helen’s tree.”61-64. (He does not discuss Helen.) The myth-ritual approach is often associatedwith the "Cambridge ritualists," on whom see Versnel 1989.41Paus. 3.19.9-10. For a survey of this and other evidence for the cults of Helen,see Wide 1893: 340-46.42Paus. 3.15.3. For the geography, see Calame 1997: 193-94. He cites an editionof Pausanias by Musti and Torelli which I have not seen. (I cite Calame 1997because it “is the equivalent of a second edition" [vi] of Calame 1977.) On thesupposed representation of Helen as a tree, standing between the Dioscuri, on acoin from Gythion, see Chapouthier [1935]1984: 90 and 149. Despite hisassertion, it is far from certain that the object between the Dioscuri is a tree.43I take these numbers from Stibbe 1989: 81. Stibbe 1989: 80-83 is a survey ofPitanê.44By "ritual," I mean a repeated, codified action in the worship of a hero or agod. On the difficulties of the term see Bremmer 1994: 38-39.45This word was applied to several different plants. It is not certain which oneTheocritus had in mind.

Edmunds Helen’s Divine Origins 13The young women are instituting the cult, which would have includedthe footrace they describe at the beginning of the Idyll (22), at themoment of Helen’s marriage.46 In the lines immediately following thosejust quoted, they return to the epithalamion which frames the poem.Their self-description matches, in general, the evocations in Aristophanesand Euripides of young women dancing at Sparta.47 Helen leads thechorus (Lys. 1314-15) or dances in the festival of Hyacinthus (Hel. 146570).48 But the songs in question cover a range of Spartan deities, and thedramatists were not thinking of the plane-tree cult.Historians of religion and scholars focusing on Helen take Idyll18 as documentary evidence of a historical cult. In the past two decades,however, literary scholars have stressed the playfulness and irony of thisIdyll.49 In lines 52-53, the young women, praying to Zeus for undyingwealth that will pass from fathers to sons, call attention to Helen's failure,known to all readers of the Idyll, to produce male offspring.50 It seems tobe impossible to proceed to a documentary level of this poem withoutnegotiating the self-consciousness mannerism of Theocritus, an exampleof which appears in the lines concerning the cult. The obviousinterpretation of the adverb translated "in Doric" (Doric because theyoung women speak and write Doric) is, as A.S.F. Gow said, absurd. "Theadverb is superfluous to the context and really represents a comment46On the footrace as part of the ritual see Calame ibid. Brillante 2003 argues thatlines 9-21 and 49-58 constitute the epithalamion and refer to the Platanistas cult,while lines 22-48 are a separate section, which refers to the Therapnê cult.47Aristoph. Lys. 1296-1321 (exodos); Eur. Hel. 1465-78 (first antistrophe ofthird stasimon). For discussion of these passages in relation to Theocr. Id. 18,see Calame 1997: 192-93; Brillante 2002: 48-49. In Alc. fr. 1 Page reference tothe cult at Platanistas has long been detected. See the bibliog

Paris and Helen, the erotic impulse of the abducting goddess is latent.16 The work of Linda Clader supported Boedeker's finding. Concentrating on the two women in the triangle Paris-Aphrodite-Helen, and beginning from Helen's epithets in Homer, Clader came to a conclusion that tended to confirm Helen's typological affinity with Aphrodite and the dawn goddess figure.17 About a decade .