Transcription

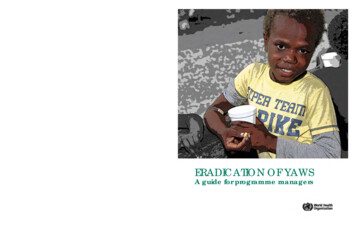

ERADICATION OF YAWSA guide for programme managersWorld H ldl Organization

A young boy from Congo with typical lesions of papilloma on the face,macules on the hand and bone swelling of the fingers. This child was curedwith a single dose of oral azithromycin. (Credit: MSF/Epicentre, Paris, France)Cover Eradication of yaws 20171213 FINAL.indd 224/01/2018 11:49:37

Eradication of yawsA guide for programme managers

Eradication of yaws: a guide for programme managersISBN 978-92-4-151269-5 World Health Organization 2018Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercialShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; igo).Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercialpurposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, thereshould be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use ofthe WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the sameor equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add thefollowing disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the WorldHealth Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. Theoriginal English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”.Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with themediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization.Suggested citation. Eradication of yaws: a guide for programme managers. Geneva: World HealthOrganization; 2018. (WHO/CDS/NTD/IDM/2018.01)Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris.Sales, rights and licensing. To purchase WHO publications, see http://apps.who.int/bookorders. Tosubmit requests for commercial use and queries on rights and licensing, see http://www.who.int/about/licensing.Third-party materials. If you wish to reuse material from this work that is attributed to a third party, such astables, figures or images, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that reuseand to obtain permission from the copyright holder. The risk of claims resulting from infringement of anythird-party-owned component in the work rests solely with the user.General disclaimers. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publicationdo not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal statusof any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers orboundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there maynot yet be full agreement.The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they areendorsed or recommended by WHO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capitalletters.All reasonable precautions have been taken by WHO to verify the information contained in thispublication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, eitherexpressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader.In no event shall WHO be liable for damages arising from its use.Printed by WHO Document Production Services, Geneva, Switzerland.WHO/CDS/NTD/IDM/2018.01

s.v1. Introduction . 11.1 Background. 11.2 Overview of the eradication strategy. 11.3 Geographical distribution. 22. The disease. 42.1 Causative organism. 42.2 Transmission. 42.3 Clinical features. 42.4 Diagnosis and differential diagnosis. 52.5 Treatment. 83. The eradication strategy. 113.1 Technical definitions. 113.2 Operational definitions. 123.3 Criteria for interruption of yaws transmission. 123.4 Implementation steps. 153.5 Provision of azithromycin and procurement of diagnostic tests. 183.6 Structures for yaws eradication at country and global levels. 184. Supervision, monitoring and surveillance. 194.1 Supervision and monitoring. 194.2 Indicators. 194.3 Follow-up activities after total community treatment campaigns . 205. The post-zero case phase . 225.1 Clinical and serological surveillance . 225.2 Verification and certification of interruption of transmission. 22References . 23Annexes . 25Annex 1. Operational definitions. 25Annex 2. Pre-treatment campaign checklist. 27Annex 3. Community information on total community treatment. 28Annex 4. Total community treatment tally sheet. 30Annex 5. Total community treatment daily summary sheet. 31Annex 6. Case investigation form. 32Annex 7. Registration of individual yaws cases form. 33Annex 8. Assessment of impact of TCT. 34i

PrefaceIn 2012, the Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO) launcheda roadmap for accelerating work to overcome neglected tropical diseases at apartners’ meeting in London, United Kingdom, with a target set for the eradication ofyaws by 2020. A publication in the Lancet that year on the efficacy of a single doseof azithromycin for the treatment of yaws was a major advance in the history of thedisease and has renewed interest in its eradication. In 2013, the Sixty-sixth World HealthAssembly adopted resolution WHA66.12 on neglected tropical diseases in support ofWHO’s roadmap. In this resolution, yaws is targeted for eradication by 2020.In response to these developments, the WHO Department of Control of NeglectedTropical Diseases organized a consultation (Morges, Switzerland, 5–7 March 2012) toprepare a strategy for yaws eradication as the basis for national eradication plans. Inlight of the new development, the International Task Force for Disease Eradication at its20th meeting (Atlanta, USA, 27 November 2012) reviewed the current global status ofyaws and endorsed the new eradication strategy.At a consultative meeting of experts (Geneva, 20–22 March 2013), two documentswere developed to guide the yaws eradication process: a guide for programmemanagers on the eradication of yaws; and procedures for verification and certificationof interruption of yaws transmission.Some 43 participants from 17 countries deliberated in depth to finalize both documents.Participants included national yaws focal points in endemic countries, experts on yaws,and regional and selected WHO country staff responsible for yaws eradication within theportfolio of the neglected tropical diseases programme. Since then, these documentshave undergone extensive review taking into consideration accumulated experiencesgained during the pilot implementation of the Morges Strategy in a number of countries.This document provides guidance for countries on how to implement activities toachieve the interruption of yaws transmission. It is intended for use by national yawseradication programmes, partners involved in the implementation of yaws eradicationactivities and WHO technical staff who provide technical support to countries in theeradication of yaws.ii

AcknowledgementsWHO acknowledges the experts and programme managers who participated in aconsultation on yaws eradication (Geneva, 2013) and provided valuable inputs to thepreparation of this document, namely:Professor Yaw Adu-Sarkodie, School of Medical Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah Universityof Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana; Dr Nsiire Patrick Agana, National YawsEradication Programme, Ghana Health Service, Box 493, Korle-Bu, Ghana; Dr DidierAgossadou, Programme national de lutte contre l’ulcère de Buruli et la lèpre, Ministèrede la Santé publique, 06 BP 2572, 06 BP 3029, Cotonou, Benin; Professor Henri Assé,Programme national de lutte contre l’ulcère de Buruli, Ministère de la Santé publique,22 BP 688, Abidjan 22, Côte d’Ivoire; Dr Ron Ballard, Center for Global Health, Centersfor Disease Control and Prevention, 1600, Clifton Road NE, Mailstop D-69, Atlanta, GA30333, USA; Dr Gilbert Ayelo, Centre de dépistage et de traitement de l’ulcère deBuruli d’Allada, 01 BP 875, Cotonou, Benin; Dr Sibauk Vivaldo Bieb, Health Department,Ministry of Health, Level 3, AOPI Centre, PO Box 807, Wagani, 131, National CapitalDistrict, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea; Dr Bernard Boua, Programme national delutte contre les maladies tropicales négligées, Ministère de la Santé publique, de laPopulation et de la Lutte contre le SIDA, BP 883, Bangui, Central African Republic; DrMatthew Coldiron, Epicentre – Médecins sans Frontières, 55, rue Crozatier, 75012 Paris,France; Professor Frank Dadzie, 284 Thornbush Lane, Lawrenceville, GA 30046, USA; DrAditya Prasad Dash, WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia, Rooms 531–537, ‘A’ WingNirman Bhavan, Maulana Azad Road, New Delhi 110011, India; Mr Javan Esfandiari,Chembio Diagnostic Systems Inc, 3661 Horseblock Road, Medford, NY 11763, USA; DrPadmasiri Eswara Aratchige (WHO Country Office, c/o WHO Regional Office for theWestern Pacific, PO Box 2932, Manila 1000, Philippines; Dr David Fegan, Unit 17, 331Gregory Terrace, Springhill, Brisbane, QLD 4000, Australia; Dr Sudhir Kumar Jain, YawsEradication Programme of India; Dr Walter Kazadi Mulombo, WHO Country Office, POBox 5896, Boroko, Papua New Guinea; Dr Yiragnima Kobara, Programme national delutte contre l’ulcère de Buruli et la lèpre, B.P. 81236, Lomé, Togo; Dr Jacob Kool, WHOCountry Liaison Office, PO Box 177, Port Vila, Vanuatu; Dr Cynthia Kwakye, GreaterAccra Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Box 184, Amasaman, Accra, Ghana;Professor Sheila A. Lukehart, Departments of Medicine/Infectious Diseases and GlobalHealth, School of Medicine, Box 359779, Harborview Medical Center, 325 Ninth Avenue,Seattle, WA 98104, USA; Professor David Mabey, Clinical Research Department, LondonSchool of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT, UK; Dr MichaelMarks, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Keppel St, London WC1E 7HT, UK;Professor em. André Meheus, University of Antwerp, Campus Drie Eiken, Universiteitsplein1, B-2610 Antwerp, Belgium; Dr Oriol Mitjà, Department of Medicine, Lihir Medical Center,PO Box 34, Lihir Island, New Ireland Province of Papua New Guinea; Dr Richard Nesbit,16 Manning Street, Queens Park, Bondi, NSW 2022, Australia; Dr Lori Newman, Controlof Sexually Transmitted and Reproductive Tract Infections, Department of ReproductiveHealth and Research, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; Dr Earnest NjihTabah, National Leprosy, Buruli Ulcer, Yaws and Leishmaniasis Control Programme,Ministry of Public Health, Yaoundé, Cameroon; Dr Damas Obvala, Programme national,Lèpre, Ulcère de Buruli, Pian, Ministère de la Santé publique, 17 rue Gampourou, Mikalou2, Brazzaville, Congo; Dr Sally-Ann Ohene, WHO Country Office, N 29 Volta Street, AirportResidential Area, Accra, Ghana; Dr Rajendra Panda, Kashikunj, Dhama Road, Dhanupali,iii

Sambalpur 768005, India; Dr Allan Pillay, Molecular Diagnostics & Typing Laboratory,United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Laboratory Reference &Research Branch, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA; Dr Chandrakant Revankar, 4305 BirchwoodCt., North Brunswick, 08902 New Jersey, USA; Dr Raoul Saizonou, WHO Country Office,Lot 27, Quartier Patte d’Oie, Cotonou, Benin; Dr Anthony Solomon, Global TrachomaMapping Project, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Keppel St, LondonWC1E 7HT, UK; Dr Ghislain Sopoh, Centre de dépistage et de traitement de l’ulcère deBuruli d’Allada, 01 BP 875, Cotonou 78, Benin; Mrs Fasihah Taleo, Neglected TropicalDiseases Program, Public Health Directorate, Health Department, P.M.B. 9009 HealthDepartment, Yatika Complex, Port Vila, Vanuatu; Dr Lasse Vestergaard, WHO CountryOffice, c/o WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, PO Box 2932, Manila 1000,Philippines; Dr Christina Widaningrum, National Leprosy and Yaws Programme, Ministryof Health, Jakarta, Indonesia; and Dr Xaixing Zhang, WHO Country Office, PO Box 22,Honiara 81, Solomon Islands.Dr Chandrakant Revankar, Public Health Medical Consultant for Neglected TropicalDiseases, and Dr Kingsley Asiedu, Medical Officer, Yaws Eradication, WHO Departmentof Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, coordinated the production of this document.This document was produced with the support of Anesvad, Spain (http://www.anesvad.org).iv

AbbreviationsDPPPCRPOCRPRTCTTPHATPPATTTWHOdual path platform (treponemal and non-treponemal) testpolymerase chain reactionpoint-of-carerapid plasma reagin testtotal community treatmentTreponema pallidum haemagglutination assayTreponema pallidum particle agglutination assaytotal targeted treatmentWorld Health Organizationvv

1. Introduction1.1BackgroundYaws is a disfiguring non-venereal disease caused by infection with the spirochaeteTreponema pallidum subspecies pertenue which is closely related to the causativeagent of syphilis and those of the other endemic treponematoses, bejel and pinta. Thedisease is endemic in certain areas of the World Health Organization (WHO) African,South-East Asia and Western Pacific regions. Of the neglected tropical diseases identifiedfor elimination and eradication, yaws is one of two diseases targeted for eradication(1). In 1949, the Second World Health Assembly adopted resolution WHA2.36, whichaddresses yaws, bejel and pinta as major public health problems that need attention (2).About 50 million people were treated with a single dose of long-acting penicillin duringthe mass treatment campaigns conducted by WHO and the United Nations Children’sFund between 1952 and 1964, and the prevalence of yaws disease was reduced bymore than 95% from 50 million to 2.5 million (3). The lack of sustained political commitmentand resources slowed the campaign’s progress to eradicate the disease. As a result, bythe late 1970s the disease had begun to resurge, prompting the Thirty-first World HealthAssembly in 1978 to adopt resolution WHA31.58 to renew efforts towards controllingendemic treponematoses in West Africa, but implementation of the resolution wasnot sustained. Subsequently, in 1995, WHO estimated 2.5 million cases of the endemictreponematoses (mostly yaws), with an incidence of 460 000 new cases per year (4).1.2Overview of the eradication strategyA new treatment strategyA single intramuscular dose of long-acting penicillin has long been used in masstreatment campaigns in areas where yaws is endemic. In 2012, the efficacy of a singleoral dose of azithromycin (30 mg/kg body weight) in curing the disease was published(5,6). The same year, WHO held a consultation of yaws experts in Morges, Switzerlandand recommended mass treatment using single-dose oral azithromycin to eradicatethe disease by 2020. This new treatment strategy has been referred to as the MorgesStrategy (3).New treatment strategy for yaws eradication (3)WHO recommends a single dose of oral azithromycin (30 mg/kg body weight), which isto be used in the new treatment policies, during the initial campaign of total communitytreatment (TCT), followed by total targeted treatment (TTT) to achieve the completeinterruption of transmission (absence of new cases of yaws) globally by 2020.Interruption of transmission is verified by: (i) the absence of any report of an indigenous,infectious yaws case for 3 consecutive years; and (ii) the absence of new sero-reactorsfor 3 consecutive years among children in the community aged 1–5 years.Accordingly, countries where yaws is endemic should reach zero new cases by 2020followed by 3 years of clinical and serological surveillance to confirm the permanentabsence of transmission.1

Number of reported cases of yaws, 2008-2015, latest year available 10 000Previously endemic (current status unknown)1 000–9 999No previous history of yaws 1 000Not applicableInterrupted transmissionFigure 1. Distribution of yaws, worldwide, 2008–2015 (Source: reference 7)Table 1. Distribution of yaws endemic countries, by WHO regionWHO regionGroup A.1InterruptedtransmissionandcertifiedGroup A.2InterruptedtransmissionPendingverificationGroup A.3CurrentlyendemiccountriesGroup BPreviouslyendemiccountriesGroup CCountrieswith nohistory ofyawsAfrican0082811Totalnumber East Asia1a023511Western pean00005454Total111484118218Source: reference 8aIndia was certified free of yaws by WHO in May 2016 (9).bEcuador reported interruption of yaws transmission in 1998 but has not been certified (10).The Philippines confirmed cases of yaws in 2017 (11) in addition to Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands andVanuatu.c1.3Geographical distributionA review of the historical and current literature on yaws from 1950 to 2013 indicatesthose countries where the disease has been endemic (Table 1). Two principal reasonsunderpin this information:1. In the 1950s, there was no formal procedure to verify the interruption of transmission and certify countries that might have previously achieved eliminationof yaws. Hence, in many of these countries, the current status remains unknown.2

2. Since the 1990s, formal reporting of yaws from a number of countries to WHOhas ceased so it is unclear whether these countries no longer have yaws orhave stopped reporting.Based on the available information (8), countries have been classified into three groupsfor the purposes of verification and certification (Table 2). Figure 1 shows the globaldistribution of yaws for the period 2008–2015 and Table 3 the countries reporting yawscases in 2008–2015 (7).Table 2. Classification of countries for certification of interruption of yaws transmissionGroup ACountries whose status of yaws endemicity is currently knownA.1Countries that have interrupted transmission and have been certified by WHOA.2Countries that have reported interruption of transmission in recent years but whichneed to be verified and certified by WHOA.3Countries with ongoing transmission for which activities to interrupt transmission are tobe implemented as per the Morges StrategyGroup BCountries with a previous history of yaws in the 1950s but no report since 2000 (currentstatus unknown)Group CCountries with no history of yaws but that need to be certified for the purpose ofglobal eradication.Table 3. Number of yaws reported cases, worldwide, 2008–2015CountryNumber of cases aBeninNDND45ND11NDNDND56Côte DND80213359975304632084Central 197NDNDND843DemocraticRepublic of 197102988628584208601Solomon 803GhanaTogoAsia and PacificIslandsIndonesiaPapua NewGuineaTotalND, no data availableSource: reference 73

2. The disease2.1Causative organismYaws is caused by infection with Treponema pallidum subspecies pertenue, a spiralbacterium (spirochete) closely related to the causative organism of syphilis. Relatedspirochetes are the cause of the other nonvenereal treponematoses bejel (T. pallidumsubspecies endemicum) and pinta (T. carateum).2.2TransmissionYaws is transmitted from person to person by direct skin contact with fluid from untreatedearly, infectious lesions (skin papillomas and ulcerations). Although the lesions may healspontaneously, some lesions may recur. Without treatment, the disease may resolvespontaneously or become latent and re-emerge as late yaws. Late yaws lesions of 2years or more (palmar and plantar hyperkeratotic lesions, bone lesions) are generallynot infectious.Cases of yaws are often seen in temporal clusters within neighbouring communities,as transmission occurs primarily among children at home, at school or at play (12).Poor hygienic conditions (limited access to water) and overcrowding are some of thefactors that are believed to promote transmission of the disease.About 75% of new yaws cases are seen among children aged less than 15 years (13).The incubation period is between 9 and 90 days, with an average period of 21 days(14).2.3Clinical featuresThe clinical manifestations of untreated disease present in the following stages (see alsoAnnex 1, Table A1):Primary stage: A papule (a raised lesion) forms at the organisms’ site of entry (suchas a micro abrasion) after an incubation period of 9–90 days. The papule maythen develop into a small yellowish cauliflower-like lesion (papilloma), which growsgradually and develops a punched-out centre covered with a yellow crust (ulcer andulceropapilloma). In 65–85% of cases, the primary lesions of yaws are seen on the legsand ankles (15,16). However, they may be found on the face, neck, armpits, arms,hands and buttocks.The initial lesions, which are highly infectious, may take 3–6 months to heal, leaving apitted scar with dark margins.Secondary stage: The secondary stage of yaws is characterized by more generalizedlesions, which may appear on the face, neck, armpits, arms, legs and buttocks. Theselesions may also occur on the soles of the feet, forcing the patient to walk in an oddposition; this condition has been termed “crab-yaws” (hyperkeratosis).Secondary lesions occur following spread of the causative organism to the bloodand lymph, and multiple lesions most commonly within the first 2 years following the4

appearance of the primary yaws lesion. Joint pain (arthralgia) and malaise are probablythe commonest, nonspecific symptoms of secondary yaws.Latent yaws: If left untreated, the infectious lesions of primary and secondary yaws willheal spontaneously and the disease may enter a period of latency with no physicalsigns. Latent yaws can only be detected as a result of serological testing.Tertiary stage: Although spontaneous healing may occur in many cases, a minoritymay progress from latency to the tertiary stage. This destructive, non-infectious stageof the disease is characterized by gumma formation and may appear after a variableperiod of latency. This stage affects the bones, joints and soft tissues, and frequentlyleads to deformities of the skin, cartilage and bone. Such cases may develop severedisfigurement of the face and legs, resulting in disabilities that prevent children fromattending school and adults from working. Thus, the socioeconomic and humanitarianimpact of yaws justifies intensification of yaws eradication activities (17).2.4Diagnosis and differential diagnosisAll individuals with suspected yaws lesions should be examined by trained health workers.A clinical diagnosis should be established based on the patient’s history, endemicity ofyaws in the area and characteristics of the lesions. Health workers should refer to theWHO yaws recognition booklet (18).2.4.1Clinical diagnosisA clinical diagnosis is based on the following features:–– History of living in or having lived in a yaws endemic area;–– Age of an individual (more common among children aged 15 years);–– Clinical appearance of skin/bone lesions suspicious of yaws (papilloma,ulceropapilloma, ulcer, papule, macule, see Annex 1 Table A1);–– Typical distribution being most common sites: lower limbs (70%); upper limbs (11%);trunk (6.2%); head and neck (8.2%); and multiple sites (4.0%).Based on the clinical findings, the individual will be classified as:–– Suspected yaws case (pending serological confirmation); or–– Non-yaws case.If health workers have difficulty confirming (or doubt) the diagnosis, the suspected yawscase remains on a list of suspects for subsequent examination by more experiencedhealth staff (nurse or doctor). This step is critical after the initial total community treatment(TCT) campaign to ensure the reliability of any reported case. During a TCT campaign,everyone is treated.5

Figure 2. Dual path platform (non-treponemal and treponemal) point-of-care test – Interpretation ofresults (Source: reference 19)2.4.2Serological confirmation of clinically diagnosed yaws casesTesting for treponemal and non-treponemal antibodies should be done to confirma diagnosis of yaws so that reporting of cases by countries will shift from clinicallysuspected cases to laboratory-confirmed cases. Traditional laboratory methods suchas rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and Treponema pallidum haemagglutination assay(TPHA) or Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA) testing can beused, but the delay in obtaining test results may negatively impact early treatment.Treponemal point-of-care (POC) tests can be used in the field for rapid screening andto exclude non-yaws cases, but subsequent confirmation of positive cases is necessaryusing a non-treponemal test. Treponemal and non-treponemal antibodies can also besimultaneously detected using a dual POC test such as the dual path platform (DPP)syphilis screen and confirm assay (19). Both tests can be performed by trained healthworkers in the field using a finger-prick blood sample and the results read within 20minutes, thus facilitating immediate treatment. Typical results obtained when usingthe DPP indicating different patterns of reactivity and their interpretations are shownin Figure 2.The dual DPP test has been found to be sensitive and specific for confirmation of bothsyphilis and yaws (20–23) and is easy to apply under field conditions.6

A specimen containing treponemal and non-treponemal antibodies exhibits three lines(treponemal, non-treponemal and control) in a developed test (Figure 2b), indicating aconfirmed reactive sample, while a specimen containing neither treponemal nor nontreponemal antibody will exhibit only a control line (Figure 2a). Interpretations of otherpatterns of reactivity are also shown (Figure 2c and 2d). Note: Reactive results do notnecessarily mean that the lesion is active yaws, as it could be caused by other agents.By detecting both treponemal and non-treponemal antibodies, the use of this testshould greatly reduce the rates of overtreatment inherent in current (treponemalonly) rapid testing and permit a single point-of-care device to be used for yaws serosurveillance.Where available, RDT and DPP tests may be used in combination (see Figure 3).Although both treponemal and dual POC tests are easy to perform, strict adherenceto the manufacturers’ instructions is necessary to ensure accuracy. Adoption of POCtests at clinical sites requires ongoing

Buruli d'Allada, 01 BP 875, Cotonou 78, Benin; Mrs Fasihah Taleo, Neglected Tropical Diseases Program, Public Health Directorate, Health Department, P.M.B. 9009 Health Department, Yatika Complex, Port Vila, Vanuatu; Dr Lasse Vestergaard, WHO Country Office, c/o WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, PO Box 2932, Manila 1000,