Transcription

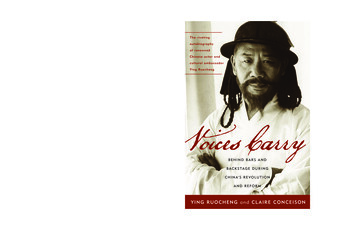

voices pb9/10/082:45 PMPage 1“This autobiography of Ying Ruocheng offers us a rare treat: a completely new vantagepoint from which to view twentieth-century China. Ying was a Manchu and a Catholic, anactor and a translator, a political prisoner and a vice minister of culture, as well as being aman of subtlety and wit. Claire Conceison has done us a real service in making thisunusual life available to the general reader.”—JONATHAN SPENCE, author of The Search for Modern ChinaYINGandCONCEISONBIOGRAPHY CHINAAsian Voices Series Editor: MARK SELDENChinese actor andFor orders and information please contact the publisherYi n g Ru o c h e n gBEHIND BARS ANDBACKSTAGE DURING CHINA’SREVOLUTION AND REFORMCLAIRE CONCEISON collaborated with YING RUOCHENGon his autobiography until his death in 2003 and has sincecompleted the project for him. She is associate professor ofdrama at Tufts University and an active translator and director.cultural ambassadorVoices CarryVoices Carry is the moving autobiography of one of China’s most prominent citizens ofthe twentieth century. Ying Ruocheng’s lively narrative takes us from his prison cell duringthe Cultural Revolution back to the princely palace of his childhood. In vivid detail, hedescribes his unconventional education during China’s revolution, which ultimately led tohis theatrical work in the era of reform, ranging from a partnership with Arthur Miller onDeath of a Salesman to roles in the films The Last Emperor and Little Buddha. The memoirof this internationally renowned actor, director, translator, and high-ranking governmentofficial during events in Tiananmen Square in 1989 provides a rare glimpse behind thescenes of contemporary Chinese culture and politics.Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.Cover photos: (front cover) Ying Ruocheng as Emperor Kublai Khan in the 1982 NBC miniseries MarcoPolo (from the collection of Ying Ruocheng). (back cover) Ying Ruocheng and Claire Conceison at Ying’shome in 2001 with a portrait of his late wife, Wu Shiliang (courtesy of Claire Conceison).BEHIND BARS ANDB AC K S TA G E D U R I N GC H I N A’ S R E VO LU T I O NCover design by Jen Huppert DesignISBN-13: 978-0-7425-5555-6ISBN-10: 0-7425-5555-0Rowman &LittlefieldA wholly owned subsidiary ofThe Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200Lanham, Maryland ographyof renowned“Ying Ruocheng . . . is, of course, a star in China. . . . [He] is not only a translator andactor but of necessity a kind of diplomat. . . . [He] has been my rock, a man of doubleconsciousness, Eastern and Western, literary and show business.”—ARTHUR MILLER, from “Salesman” in Beijing“Ying Ruocheng was an extraordinary individual, a man of integrity and creativity whosestory must be more widely known. Through this brilliant collaborative telling with ClaireConceison, we understand how he inspired so many and we learn how the arts can impactworld events.”—RALPH SAMUELSON, Asian Cultural CouncilThe rivetingAND REFORMYING RUOCHENG and CL AIRE CONCEISON

Voices Carry

ASIAN VOICESA Subseries of Asian/Pacific/PerspectivesSeries Editor: Mark SeldenTales of Tibet: Sky Burials, Prayer Wheels, and Wind Horsesedited and translated by Herbert Batt, foreword by Tsering ShakyaThe Subject of Gender: Daughters and Mothers in Urban Chinaby Harriet EvansPeasants, Rebels, Women, and Outcastes: The Underside of Modern Japanby Mikiso HaneComfort Woman: A Filipina’s Story of Prostitution and Slavery under the Japanese Militaryby Maria Rosa Henson, introduction by Yuki TanakaJapan’s Past, Japan’s Future: One Historian’s Odyssey–by Ienaga Saburo , translated and introduced by Richard H. MinearI’m Married to Your Company! Everyday Voices of Japanese Womenby Masako Itoh, edited by Nobuko Adachi and James StanlawQueer Japan from the Pacific War to the Internet Ageby Mark McLellandBehind the Silence: Chinese Voices on Abortionby Nie Jing-BaoRowing the Eternal Sea: The Life of a Minamata Fishermanby Oiwa Keibo, narrated by Ogata Masato, translated by Karen Colligan-TaylorThe Scars of War: Tokyo during World War II: Writings of Takeyama Michioedited and translated by Richard H. MinearGrowing Up Untouchable in India: A Dalit Autobiographyby Vasant Moon, translated by Gail Omvedt, introduction by Eleanor ZelliotExodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold Warby Tessa Morris-SuzukiChina Ink: The Changing Face of Chinese Journalismby Judy PolumbaumRed Is Not the Only Color: Contemporary Chinese Fiction on Love and Sex between Women,Collected Storiesedited by Patricia SieberSweet and Sour: Life-Worlds of Taipei Women Entrepreneursby Scott SimonDear General MacArthur: Letters from the Japanese during the American Occupation–by Sodei Rinjiro , edited by John Junkerman, translated by Shizue Matsuda,foreword by John W. DowerUnbroken Spirits: Nineteen Years in South Korea’s Gulagby Suh Sung, translated by Jean Inglis, foreword by James PalaisA Thousand Miles of Dreams: The Journeys of Two Chinese Sistersby Sasha Su-Ling WellandDancing in Shadows: Sihanouk, the Khmer Rouge, and the United Nations in Cambodiaby Benny WidyonoFor more books in this series, go to www.rowmanlittlefield.com/series

Voices CarryBehind Bars and Backstageduring China’s Revolution and ReformYing RuochengandClaire ConceisonROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC.Lanham Boulder New York Toronto Plymouth, UK

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC.Published in the United States of Americaby Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706www.rowmanlittlefield.comEstover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United KingdomCopyright 2009 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrievalsystem, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information AvailableLibrary of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataYing, Ruocheng.Voices carry : behind bars and backstage during China’s Revolution and reform /Ying Ruocheng and Claire Conceison.p. cm. — (Asian voices)Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN-13: 978-0-7425-5554-9 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN-10: 0-7425-5554-2 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN-13: 978-0-7425-5555-6 (paper : alk. paper)ISBN-10: 0-7425-5555-0 (paper : alk. paper)ISBN-13: 978-0-7425-5746-8 (electronic)ISBN-10: 0-7425-5746-4 (electronic)1. Ying, Ruocheng. 2. Actors—China—Biography. 3. Theatrical producers anddirectors—China—Biography. 4. Translators—China—Biography. 5. Motion pictureactors and actresses—Biography. 6. College teachers—United States—Biography. 7.Beijing (China)—Biography. 8. China. Wen hua bu—Officials and employees—Biography. 9. China—History—1912–1949—Biography. 10. China—History—1949–—Biography. I. Conceison, Claire, 1965– II. Title.CT1828.Y55A3 2009951.04092—dc22[B]2008023410Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of AmericanNational Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed LibraryMaterials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

In loving memory of Wu ShiliangIn loving hope to Bayan

ContentsAcknowledgmentsixIntroductionClaire ConceisonxvPart I: The Adventures of Prison LifeChapter 1My First Year Behind BarsChapter 2The Prison at Jixian327Part II: Family History and Early EducationChapter 3The Ying Legacy61Chapter 4A Princely Childhood95Part III: Professional Life in Arts and PoliticsChapter 5My Stage Career119Chapter 6Cultural Diplomacy157EpilogueClaire Conceison187Timeline193vii

viii ContentsFamily Tree197Notes199Bibliography235Index239About the Authors245

AcknowledgmentsIt is ironic that the kindness, wisdom, and assistance of so many was necessary to produce the life narrative of one single individual in his own words,but Ying Ruocheng’s story could not have been told the way he wanted it tobe without the contributions of the following people. I have been humbledby their enthusiasm for the project and I am deeply grateful.Above all, of course, I must thank Ying Ruocheng, a great man who became my good friend. It is an understatement to say that it was an honor,privilege, and pleasure to sit by his side and listen to his remarkable story inhis remarkable prose. Our partnership, which I discuss in the introduction,was a unique experience in my life. It is my sincere wish that the pages thatfollow represent his voice, life, and legacy the way he intended.Ying Ruocheng had many significant partnerships in his life. The greatest,of course, was with his wife Wu Shiliang, who, as you will read, was missedby her husband every day after her death in January 1987. One of Ying’s pleasures in narrating his life experiences in English was that it brought backfond memories of speaking English with her.Another great partnership in Ying’s life was with Arthur Miller—togetherthey collaborated on a Chinese production of Death of a Salesman in Beijingin 1983. Mr. Miller had kindly agreed to author the foreword to this book,but he passed away in February 2005 before writing it. I am grateful to himfor his four years of correspondence with me and his support of the project,as well as his deep affection for Ying Ruocheng. In the absence of his foreword, I have selected excerpts from his published book “Salesman” in Beijingix

x Acknowledgmentsto share in the introduction. I also wish to thank Julia Bolus and the late IngeMorath for their kindness, as well as John Jacob and Emma Winter of theInge Morath Foundation in New York.My deepest gratitude lies with the Ying family, especially Ying Ruocheng’sdaughter Xiaole (Felicia King) and son-in-law Jin Yijian (John King); his sonYing Da and daughter-in-law Liang Huan; his brothers Ying Ruocong, YingRuoshi, and Ying Ruozhi; his nephews Ying Zhuang and Ying Ning; and hissister Ying Ruoxian. They opened their homes—and their memories—to me,and trusted me with their contents (including fragile photographs and precious moments in their lives), for which I am forever grateful. YingRuocheng’s “adopted sister” Stella Shen (Han Gongchen) provided a richarchive of documents and photographs pertaining to both Ying Qianli andYing Ruocheng that were immensely valuable to the book. Chen Yanni(Jenny Ma) likewise offered materials and her friendship.Many of the hours I spent with Ying Ruocheng at his home and in thehospital were also spent with his faithful nurse, Shao Derong. She took wonderful care of him, and her laughter eased his pain on countless occasions.Several of Ying Ruocheng’s colleagues at the Beijing People’s Art Theatrecontributed to this project by sharing their reminiscences and assisting me inlocating relevant archival material. Most helpful of all was my “big brother”Yang Lixin, whose love and respect for his mentor—and protective care forme—solidified my friendship with Ying before our collaboration began andsustained me throughout every stage, even after his death. Pu Cunxin andLin Zhaohua also extended kind support, as did Meng He, Fu Yunjun, LiuZhangchun, Bai Yan, Su Dexin, Yu Wenping, Chen Qiuhuai, Ma Xin, FengLiping, Qi Jihua, Yin Wenzhen, Xia Meng, and Wu Jianhua. Gao Xingjian,Ying’s former colleague from both the theatre and the Foreign LanguagesPress, spoke to me about their experiences together during our conversationsat his home in Paris in June 2006.The staff of the Foreign Affairs Office at Beijing’s Central Academy ofDrama welcomed me back “home” every year, allowing me to maintain an affiliation with the institution while I continued the project. I am especiallygrateful to Gao Haiyun, Zhou Shaoyu, and Bian Baorui. My dear mentorShen Lin offered lively encouragement. Special acknowledgment is due HanYonggang, a stranger who befriended me and tried to help me gain entranceto the former Prince Qing’s palace on Dingfu Road (Ying Ruocheng’s childhood home, now a government office that is off limits to the public) and alsoled me through the grounds of the adjacent former site of Furen Universityand Furen Middle School. Delightful Yu Rongjun and his staff looked afterme during my brief stays in Shanghai.

Acknowledgments xiMy annual residences in China would not have been possible without substantial financial support. The seed money for the first phase of the projectin 2001 was provided by the Asian Cultural Council—I am grateful to RalphSamuelson for his many years of encouragement, which go above and beyondthe financial. Colleagues and administrators at Tufts University helped tofund the final phase of the project after Ying’s death through small but significant Faculty Research Awards in 2006 and 2007, a Faculty ResearchSummer Grant in 2005, and ample time to write and conduct research during two Junior Faculty Research leaves. Much of my collaboration with YingRuocheng was facilitated by a generous Pacific Rim Research Grant from theUniversity of California, Santa Barbara, administered by Tim Schmidt andthe wonderful staff at ISBER in 2003–2004. Their funding also allowed meto hire several outstanding students to assist in transcribing audio and videotape. Graduate students Jason Scott and Adrienne MacIain and undergraduate Mandi Muehlbauer helped at UCSB, and my faithful team of undergraduate superwomen at the University of Michigan consisted of Katie Gleason,Su Panetta, Justine Silver, Elizabeth Bovair, Kristina Sepe, and Yiting Liu.Beth, Kristina, and Yiting continued with the project long after their officialcommitment, with Yiting taking on the particularly challenging task oftranslating Ying Ruocheng’s prison notes scrawled in miniscule charactersthat had faded with time. Ying was delighted when I presented him with agroup photograph of “his girls.”Sidonie Smith and Peter Ho Davies at the University of Michigan offeredadvice as I entered the new territory of autobiography. David Rolston and hisfabulous family provided me with a second home in Ann Arbor—while EnaSchlorff provided the actual roof over my head—and Margaret Baker provided prayer and care. Tom Weisskopf and everyone at the Residential College made academic life a pleasure, and Coach Lloyd Carr and his entire staffat Michigan Football provided frequent smiles and hugs that helped me morethan they ever knew.At UCSB, President Henry Yang and his wife Dilling cheered me on, alongwith my dean, David Marshall, my department chair, W. Davies King, and mycherished friends in Asian studies, Ron and Susan Egan and Michael Berry.Among my wonderful current colleagues at Tufts University, I would especiallylike to thank Barbara Grossman, Laurence Senelick, Xueping Zhong, FrancieChew, and Jay Shimshack; my deans Susan Ernst, Kevin Dunn, Andrew McClellan, and Robert Sternberg; Provost Jamshed Bharucha; and PresidentLawrence Bacow. I am also indebted to the students in my graduate seminar onmodern and contemporary Chinese theatre during spring 2006 and fall 2007,who read early drafts of chapters and offered helpful comments.

xii AcknowledgmentsAt Harvard University, Sophia Huang assisted with scanning photographs, while Tony Saich kindly examined Ying’s prison notebook with me.Julian Chang kept the notebook safe for several years, and donated moretime, effort, and advice to this project than I can ever properly thank him for.Many acquaintances from near and far tolerated my creative questionsduring the course of my research, responding cheerfully with priceless insights and citations. These people include Robert Chi, Yomi Braester, JeffreyWasserstrom, John Weinstein, Carsey Yee, Siyuan Liu, Timothy Wong,Colin Mackerras, Daniel Abramson (via Robin Visser), Wang Ke-wen (viaRonald Suleski), Wen-ling Lin, Dassia Possner, Sharon Pei, Rosa Tsai, Fr.Jeremy Clarke, SJ, and Fr. Donald Glover, MM. I am grateful to all of them,and their efforts are reflected in many of the rich endnotes that enhance thereading experience of Ying Ruocheng’s narrative. Particularly generous withher time and resources was reference librarian Chao Chen at Tufts University’s Tisch Library. A special thank-you is also due Jonathan Spence andCalvin Chen, who carefully reviewed the final draft of the manuscript.During a fleeting moment as I completed my graduate work at CornellUniversity, Joseph Roach (perhaps unknowingly) helped convince me thatYing Ruocheng’s story needed to be told in the West. Pete and Amy Mangurian and Susan Sullivan offered immense support during the eight years ofthe project, along with my parents, siblings, and their families. As I enteredthe home stretch, Colleen Rua and Rebeca Plantier provided pricelessfriendship and advice—and Christopher Masters came along and suited uplate in the game, leading in unexpected ways to the successful completion ofthis book. I hope they will be among the first to read it, and I extend to themmy sincere gratitude and deep affection.There are a few people I wish to thank most of all. Motivated by her ownfriendship and collaboration with Ying Ruocheng, Felicia Londré consistently wished for this book to materialize and did everything within herpower to help make that happen. In 2001, Mark Selden accepted a long email from me with documents attached, and graciously became my editor andadvisor, sticking by me ever since. The fabulous Susan McEachern fromRowman & Littlefield joined him in 2006 and together they, assisted by Jessica Gribble, Janice Braunstein, Carrie Broadwell-Tkach, and Brooke Bascietto, saw me through the final stages of this book with patience, kindness,wisdom, and good humor. Zhang Fang jumped on board to translate the bookinto Chinese, and Liu Zhangchun helped facilitate a contract in China, making Ying’s autobiography available to those who knew him best and lovedhim most. Finally, the very busy Ying Da provided immeasurable assistance,including polishing the Chinese translation to make it sound as much as pos-

Acknowledgments xiiisible like his father’s voice. The title of the Chinese version of this book isShuiliu yunzai.My father, Manuel Conceison, viewed every transcript and videotape overthe years, was the first to read the final manuscript, and listened to almostevery detail of my experience with Ying Ruocheng. How I wish these twomen who have had such a profound impact on me could have met.—C.C.

IntroductionClaire ConceisonOccasionally in our lives, we encounter human beings who are so unique andcompelling that we wish we could introduce them to everyone we know. Werevel in the moments we are blessed to enjoy alone with them, and at thesame time are eager to share their presence with others. I am sure there issomeone in your life that fits this description.For me, this person was Ying Ruocheng. It was not only because he was ahugely important figure in twentieth-century Chinese theatre and politicsthat I wanted others to know him—though he was. In an obituary, TonyRayns described Ying as “a highly cosmopolitan intellectual and an exceptionally gifted actor-director . . . the last of the cultural movers and shakersproduced by China in the early decades of the twentieth century.”1 As youwill read below, Ying hailed from an important family and carried on thatlegacy, making crucial contributions to Chinese society during a century ofpolitical, intellectual, and social upheaval. He also made a name for himselfon the stage and screen, and as a cultural diplomat.At the same time, he was incredibly down to earth and a master of theEnglish language, his adopted second tongue. A gifted storyteller with irresistible charm and a brilliant sense of humor, he was warm, unassuming, andslightly—delightfully—mischievous. His colleagues at the Beijing People’sArt Theatre remembered him after his death in 2003 as a life-giving force; akind-hearted magnanimous person with incomparable gifts of resourcefulnessand creativity; a level-headed gentleman who never lost his temper; aneternal optimist in the face of bitter life struggles and a debilitating terminalxv

xvi Introductionillness; a rare renaissance man with innovative vision who could relate topeople of any generation; a truly noble intellectual who nevertheless considered no task to be below him; and an extraordinary individual who couldnever be replaced.2Foreigners as well as Chinese found it impossible not to fall under the spellof his charisma and authenticity. Professor Felicia Londré said it best when,after a long conversation with Ying about Eastern and Western theatre, shewrote in her diary: “What a wonderful man and brilliant mind he is . . . [he]hobnobs with royalty, heads of state, and international arts celebrities, yet itwas like having a fireside chat with a best friend.”3Ying Ruocheng joined forces with some of the most impressive individuals inhis various fields. As an actor, he is best known for his roles in BernardoBertolucci’s films The Last Emperor and Little Buddha. He is also widely recognized for his performance as Willy Loman when Arthur Miller directed Death ofa Salesman in Beijing in 1983. The following year, Miller introduced him toDustin Hoffman at the Broadway performance of the play and the two actorscompared notes about playing Willy on opposite sides of the globe, and a decadelater Ying directed Salesman at the College of William and Mary. As China’svice minister of culture from 1986 to 1990, his feats included bringing CharltonHeston to Beijing in 1988 to direct Herman Wouk’s The Caine Mutiny Courtmartial. Ying was known as “one of China’s most famous actors and a brillianttranslator,” fondly remembered for his savvy interpreting for Bob Hope in 1979as well as his numerous literary renderings of classic plays from English into Chinese and vice versa. He made his mark as a director in projects like his partnership with England’s Toby Robertson on Measure for Measure in 1982, a production that “achieved a level of excellence worthy of admiration and emulationanywhere in the world.”4 Salesman, Mutiny, and Measure all reached the Chinese public because Ying translated them.Ying Ruocheng was not the only gifted member of the Ying family, thoughhe was considered exceptional even in the eyes of his talented siblings, each ofwhom excelled in some form of academics, art, or athletics. His brother Ruoshiis a renowned painter, whose twin Ruozhi is a successful engineer. Anotherbrother, Ruocong, is an accomplished architect; Ruocai excelled in women’sbasketball; and sister Ruoxian, the only sibling to settle outside of China, is aphysicist at Columbia University. Ying Ruocheng’s daughter Xiaole is an artistin Chicago, while son Ying Da has become one of China’s most prominentcelebrities as a film and television actor, television director-producer and talkshow host.I met Ying Ruocheng in 1991 when he was directing his translation ofGeorge Bernard Shaw’s Major Barbara at the Beijing People’s Art Theatre

Voices Carry xviiand I was a graduate student from Harvard University conducting field workfor my master’s thesis. I had the good fortune to spend time with him againin 1994 when he appeared as a guest star in Ying Da’s wildly popular sitcomI Love My Family (Wo ai wo jia). After visiting him at his home during his illness in 1996 and 2000, I subsequently enjoyed the unique privilege of sittingby his bedside during the summers of 2001, 2002, and 2003 as he recountedto me his rich life experiences in order to publish this autobiography in English for Western readers. Each of these conversations over the course of adecade was indeed like having a fireside chat with a best friend.An Uncommon EverymanYing Ruocheng was born into an elite family—his grandmother was a descendant of China’s last imperial family and his grandfather was a high intellectual.But he hailed from a Manchu clan that was illiterate and disenfranchised; hisgrandfather was a convert to Catholicism; and he had eight siblings, two ofwhom died in their youth from tuberculosis. His humility, morality, and charitywere the products of this Manchu Catholic upbringing. He spoke of his fellowprisoners from the Cultural Revolution—many of whom were poor peasants—with the same esteem and affection with which he spoke of great playwrightslike Cao Yu or Arthur Miller, because he felt equally fortunate to have earnedtheir respect and friendship. One of the most touching passages of Ying’s autobiography is his separation from a rural childhood playmate at his family’s summer home in Wenquan after her feet were bound. As a young boy, Ying did notfully comprehend the class difference between his family with the mansion onthe hill and the children in the small dwellings below. And as an old man dying in his hospital room, he remained nostalgic for a time and place that transcended such divisions, a world in which a prince’s palace could be the homewhere educators’ children like himself romped and played.Perhaps it is this simultaneity of greatness and simplicity—of intellectualacumen and dyed-in-the-wool common sense—that made Ying Ruochengand Arthur Miller kindred spirits when they met in 1978 and collaboratedon Death of a Salesman in 1983. In China, Miller directed his own play forthe first time, and Ying appropriately played the role of Willy Loman, thaticonic figure in American drama through which Miller reinvented thetragic hero as the common man. Miller regarded Ying as a genius because ofhis skills in translation, diplomacy, and acting, but also felt that Ying wasable to embody Willy Loman in a way no other actor had before him, because he relinquished his “superiority” over the character and “gave up hisown invulnerability . . . [thereby] acknowledg[ing] his affinities with the

xviii Introductioncharacter and in the bargain transcend[ing] himself.” Miller called Ying “areal pro, yet a man full of intelligent feeling who is ready to try anything”and observed that he “has a kind of absolute control that brings Olivier tomind—he simply does what is called for, easily, directly, effortlessly.” Millermarveled at Ying’s facility in translation as well as stage acting, saying, “I amspoiled by Ying’s instantaneous and colloquial renderings. . . . [W]ith himbeside me I forget altogether that I am not understanding the Chinese; heis but a breath behind the speaker, with not a single hesitation.”This admiration was mutual, as exhibited in chapter 6 when YingRuocheng speaks at length about his partnership with Miller. It was Ying’swish that Miller would write the foreword for his autobiography, but Millerdied before the words he graciously agreed to pen actually materialized.Thanks to his detailed journal documenting their collaboration—publishedas a book titled “Salesman” in Beijing—Miller’s high esteem and personalfondness for Ying are nevertheless recorded for posterity. The day the playwould open in Beijing (May 7, 1983), Miller visited Ying and his wife WuShiliang at their home, and reflected afterward:I have never had this kind of relationship with an actor—primarily, I think, because Ying is also a scholar and approaches concepts passionately; thus he candraw feeling from ideas as well as from sheer psychological experience. . . . YingRuocheng has been my rock, a man of double consciousness, Eastern andWestern, literary and show business.5In Beijing Diary, Charlton Heston’s book detailing his 1988 experience, herecalled that “Ying Ruocheng put the full weight of his personal authorityand his creative capacity into our undertaking. Without him, Caine wouldnever have sailed.”6 As vice minister of culture (under Minister of CultureWang Meng), Ying instituted sweeping reforms in the arts at considerablerisk. A few months after Caine premiered, prodemocracy demonstrationsbegan in nearby Tiananmen Square, triggered by the death of Hu Yaobang,the man who had hand-picked Ying for his government post.7 It was a darkperiod for Ying—his beloved wife had died two years earlier and the pressureof serving as a high-ranking official in the midst of such political trauma wastaking its toll. It was not unlike trials his own father had endured before him,and Ying remained ever-mindful of this family legacy.The Ying CenturyYing Ruocheng’s father, Ying Qianli, was born in 1900, at the dawn of a century that his father, Ying Lianzhi, had helped to shape. Born in 1866, Ying

Voices Carry xixLianzhi had risen from a clan of illiterate Manchu warriors to become aprominent Catholic intellectual. Among his contributions were the founding of both a liberal newspaper in Tianjin during the twilight years of theQing Dynasty and a Catholic university in Beijing in the midst of turmoil,when the Qing had given way to unequal treaties with Western powers, ruleby warlords, and uneasy alliances and civil war between Nationalists andCommunists. Amid this political upheaval, artists and intellectuals were calling for a “new culture,” including the use of vernacular language to reach ordinary citizens for whom classical Chinese was inaccessible, and the exploration of pressing social issues of the day through literature and art.Intellectuals influenced by the May Fourth Movement imported Westernstyle spoken drama to China (via Japan, where it was already being absorbed)and Ying Ruocheng would eventually devote his life to developing moderntheatre in China and using it to promote international dialogue and understanding.8If during Ying Lianzhi’s lifetime China’s future was uncertain, during hisson’s lifetime it was uneasy. Ying Qianli aligned himself with the NationalistParty (KMT) and worked underground against the Japanese; he was imprisoned twice during Japan’s occupation of China from 1937 to 1945; and hewas whisked off to Taiwan when Chiang Kai-shek retreated there in the wakeof the Communist victory in 1949. Ying Ruocheng, a freshman in college,would never see his father again. Yi

Voices Carry Rowman & Littlefield BEHIND BARS AND BACKSTAGE DURING CHINA'S REVOLUTION AND REFORM ISBN-13: 978--7425-5555-6 ISBN-10: -7425-5555- Cover design by Jen Huppert Design BEHIND BARS AND BACKSTAGE DURING CHINA'S REVOLUTION AND REFORM voices_pb 9/10/08 2:45 PM Page 1.