Transcription

by Amy LiuThe Admission Industrial Complex:Examining the EntrepreneurialImpact on College Access

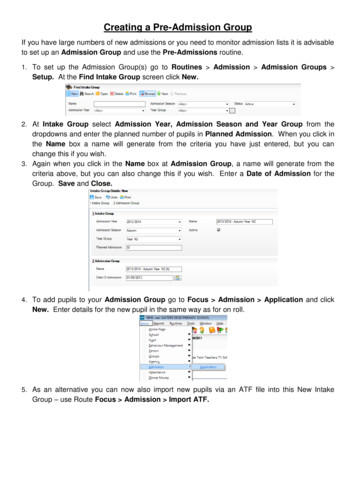

In a post-industrial society, higher education might be viewed as a “defensive necessity” (Bell 1973,p. 414). From the perspective of economic mobility, having a college degree can greatly improve thechances of moving up the income ladder (Baum and Ma 2007, Haskins 2008). Additionally, collegequality can have a significant positive effect on earnings and the pursuit of graduate education (Eide,Brewer and Ehrenberg 1998, Monks 2000; Thomas and Zhang 2005, Wolniak, et al. 2008, Zhang2005a, 2005b). As enrollment rates increase (NCES 2008), the message that one needs to pursue higher education in order to succeed in our society seems to ring louder and clearer. Nationalnews outlets ostensibly feed into this conventional wisdom with reports that admission to the nation’stop-ranking colleges and universities has grown increasingly competitive (Arenson 2008, Tyre 2008).In turn, some students have sought to leverage their own opportunities by turning to an expanding entrepreneurial admission sector. Indeed, a veritable “admission industrial complex” has sprung forth tomeet the demands of students seeking to gain an edge over their peers (Marcus 2006, Wang 2007).The entrepreneurial admission sector is comprised of commercialand sociological status attainment studies (McDonough 1997).enterprises aimed at helping students increase their odds of ad-By integrating the seemingly disparate approaches within cul-mission, as well as providing general college information to thetural and organizational frameworks, college access researchersmasses. As for-profit entities, a goal of companies in this sectorhave transformed the domain into a more robust area of inquiry.is to maximize revenue and profit. Existing research identifiesMcDonough, Ventresca and Outcalt (2000) propose an organiza-four main activities as making up the entrepreneurial realm:tional field approach to the study of college access that enables1) standardized test preparation (test prep) and tutoring, 2) privategreater understanding of how numerous factors—individuals, highcollege counseling, 3) mass media informational resources, andschools, colleges and universities, policy, and the entrepreneurial4) institutional enrollment marketing and managementsector—work in concert to structure higher education participa-(McDonough, Ventresca and Outcalt 2000). The purpose of thistion. Variables such as social class, race and ethnicity, gender,article is to build on previous scholarship by highlighting some of thehigh school context, parental and family involvement, culture, andarguments for why this sector creates the potential to perpetuatefinancial aid intersect to shape students’ decisions to pursue high-the already unequal playing field of higher education participation.er education, their understanding of the admission process, andIt then offers considerations for how three additional areas—the college choices they make (Fann 2002, Hossler, Braxton andstudent financial services, packaged and customized college tours,Coopersmith 1989, Perna, et al. 2008, Smith and Fleming 2006,and essay coaching—contribute to the inequity. It also providesSwail, Cabrera and Lee 2004, Teranishi, et al. 2004, Tierney andan account of the big business revenue of these myriad activities.Auerbach 2005, Villalpando and Solorzano 2005).In doing so, it adds to the discussion of how corporations capitalizeon the perception of “defensive necessity,” thereby escalating theFrom a field perspective, the entrepreneurial admission sec-commercial incursion on college access.tor constitutes a field in and of itself that is ripe for analysis.McDonough, et al. (2000) argue that the driving force behindThe Entrepreneurial Impact on the Field of College Accessthe growth of commoditized college knowledge is “the recipro-Previous research on college choice has encompassed three ba-cal influence of individuals and institutions, particularly throughsic approaches—social psychological studies, economic studiesthe influence of socioeconomic status” (p. 393). The field ofWWW.NACACNE T.ORGWINTER 2011 JOURNAL OF COLLEGE ADMISSION 9

Persistent scoredisparitiesbetween racial/ethnic andincome groups,as well asinequalities inaccess to andfamiliarity withstandardizedexams haveled to concernsabout therole of testsas barriers tohigher educationparticipation.entrepreneurial admission involves a complexof the company's 4.7 billion total revenue in 2008,interplay between large corporations, the media,advertising made up 25 percent and circulation andindividual actors, and social class. Given the risingsubscribers a mere 20 percent of the Washingtoncommercialization of higher education (Bok 2003,Post Company's overall revenue (Hoover's 2009d).Slaughter and Rhoades 2004), a closer examinationAlongside the national corporate providers are a slewof this sector is warranted, especially concern-of independent, locally-owned test prep and tutoringing its potential to exacerbate inequity in highercompanies. The quantity and quality of these areeducation. Three activities in particular, test prep,unknown as there are no test prep associations thatprivate college counseling, and rankings, haveorganize the industry.been at the forefront of scrutiny.Persistent score disparities between racial/ethnicTest Prep and Tutoringand income groups, as well as inequalities in accessAlthough the merits of standardized tests, their useto and familiarity with standardized exams havein the admission process and their predictive powerled to concerns about the role of tests as barriersfor postsecondary success are certainly debatableto higher education participation (Atkinson 2001,(Zwick 2004), standardized exams themselves areCarnevale and Rose 2003, NACAC 2008a, Steelebig business and therefore inextricably tied to theand Aronson 1998, Walpole, et al. 2005, Zwickentrepreneurial admission sector. The Educational2007). The issue is particularly salient given thatTesting Service (ETS), parent to the SAT and other89 percent of colleges place considerable or moder-exams, is a corporate educational player with yearlyate importance on standardized tests as a factor infinancials that include net sales of 850 millionadmission decisions (Clinedinst and Hawkins 2008).Consequently, the test prepThe Commission of a 2008 National Association forindustry is perhaps the most recognized driving force ofCollege Admission Counseling (NACAC) report ar-entrepreneurial admission. Kaplan, Princeton Reviewgues that the consequent test prep industry “wouldand Sylvan Learning are three national examples ofnot, of course, exist without two primary inputs: (1) atest coaching and tutoring corporations. According tomajority of colleges and universities require standard-Kaplan’s (2009) Web site, courses for SAT prep in theized admission tests for admission, and (2) familiesLos Angeles area range from 399 for online self-studysustain the demand for such services with disposableto 3,899 for private tutoring. However, test prep isincome and a desire to give their students ‘a leg up’only one component of these for-profit educationalin the admission process” (p. 24).(Hoover’s 2009a).1corporations’ products and services. For example,only 108 million of Princeton Review’s 139 millionThe effects of test prep in college admission can betotal revenue in 2008 came from test prep services;minor, yet significant. In a recently released NACACsupplemental education services generated thediscussion paper, Briggs (2009) notes that “coach-remaining 30 million (Hoover’s 2009c). In 2008, ofing has a positive effect on SAT performance, but theKaplan’s 2 billion revenue, only 588 million camemagnitude of the effect is small” (p. 12). Contraryfrom sales in its test prep unit. The remaining revenueto commercial claims that scores can vastly improvederived from its higher education ( 1,276 million),in the range of hundreds of points, researchers haveprofessional ( 467 million) and corporate divisionsfound that any gains from test prep activities are( 1.4 million) (Hoover’s 2009b). Notably, Kaplan iscloser to an average of 30 points, a number which isnow the supporter of its parent, the Washington Postalso the standard error of measurement for the SATCompany. Compared to Kaplan's 52 percent share(Briggs 2009). The practical significance, however,1Interestingly, ETS’ legal status is listed as private, not-for-profit (www.ets.org).10 WINTER 2011 JOURNAL OF COLLEGE ADMISSIONW W W. N A C A CN E T.ORG

of test prep effects can be much greater. In a NACAC survey thattest prep can still be important, including for racially underrep-asked about the impact of test score increases in admission deci-resented students in higher education. Using NELS data, Pernasions, Briggs finds that in some instances more than a third of(2000) finds that African-American students’ use of more thanadmission directors agreed that an increase of 10 points on theone test prep tool is a predictive variable in the probability ofmath section of the SAT or a 10-point gain on the critical read-enrolling at a four-year college or university. Such students areing portion would “significantly improve a student’s likelihood of11 percent (p .05) more likely to enroll. White students whoadmission” (p. 19). Furthermore, on the lower spectrum of SATused one test prep tool or more than one test prep tool arescores and at less selective institutions, a small increase doesfive percent (p .01) and 11 percent (p .001) more likely tothe most to improve a student’s chances of admission. Similarly,enroll, respectively. There was no significant change in prob-at higher scores on the scale and at more selective schools, aability for Latino students (p. 134). Walpole et al. (2005) findminor increase appears to have an equal or even larger impact ofthat many African-American and Latino students in their studyimproving acceptance to an institution. As Briggs states, “A 10 orare generally rather wary of standardized tests and question20 point coaching effect is clearly very practically significant if ittheir fairness. Despite the doubt, some do avail themselvescrosses a cut-off threshold” (p. 21).of low-cost and free exam prep offered by schools and outreach programs (nine percent) and find ways to take the SATA college access consequence is that students from low socioeco-more than once (40 percent) in an effort to raise their scoresnomic backgrounds, who are not able to afford test preparation and(p. 336). The quality of the free services, however, is unknownmultiple test administrations, are at greater risk of being furtherand almost none of the students had access to private and com-disadvantaged in the admission process. Studies show that socio-mercial test prep services.economic status (SES) contributes to the likelihood that studentswill use test prep services and take the exam more than once.Likening test prep activities to the use of performance-Using data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study (NELS),enhancing steroids in sports, Gayles (2009) draws a compellingBuchmann, Roscigno and Condron (2006) find that family SES isanalogy between education and athletics and questions what isa positive and significant factor in predicting test prep usage, mostconsidered fair play. He argues that test prep is anathema to fairnotably for private class and tutoring activities. Vigdor and Clotfel-play in college admission and offers benefits only to those whoter (2003) find that students who retake admission exams are fromcan afford it. However, he also acknowledges that disposing ofmore affluent families, have more highly educated parents and havesuch services will not eliminate systems of advantage. From anA college access consequence is that students from low socioeconomic backgrounds, who are not able to afford test preparation and multiple test administrations,are at greater risk of being further disadvantaged in the admission process.Studies show that SES contributes to the likelihood that students will use test prepservices and take the exam more than once.higher self-reported abilities and class rank. Their study, however,entrepreneurial admission perspective, the test prep industry isis not based upon a national dataset, but rather from analysis ofbig business and unlikely to wane.undergraduate applicant data from three selective research universities in the South. Nevertheless, their findings show that studentsPrivate College Counselingwho took the SAT three times demonstrated average score increasesIn addition to efforts to raise test scores, the competitive pressures ofof 29 and 28 points for the verbal and math sections, respectively.getting into selective colleges and universities have led some studentsto seek expert assistance from private college counselors. TheseAlthough coaching effects are small and nowhere near whatprivate admission consultants offer personalized attention and spe-commercial companies advertise (Briggs 2009), the benefits ofcialized knowledge to help students strategically navigate the complexWWW.NACACNE T.ORGWINTER 2011 JOURNAL OF COLLEGE ADMISSION 11

by engagingin the purchaseof professionalcollege knowledge,they can marketthemselves ascompetitiveproducts tohigher educationinstitutions, therebytransformingthemselves intocollege applicantcommodities.and high-stakes terrain of college admission. StudentsMcDonough (1997, 2005a, 2005b) states thatare turning to these independent counselors eithercounselors play an important and influential role,because their high schools are not providing adequateboth positively and negatively, in the field of col-college counseling or because they want to pursuelege access. She also notes that there are variousevery available advantage (McDonough, Korn andstructural and practical challenges in the domain ofYamasaki 1997, McDonough 2005b). Some examplescollege counseling that counselors, teachers,of full-service counseling providers include IvyWise andstudents, parents, and schools face. In an era ofCollege Coach. These organizations pride themselvesperceived high-stakes admission, some students andon offering prospective students a comprehensive,parents have actively sought the help of private collegetotal package approach, often bolstered by their coun-counselors (McDonough, 2005b). These individualsselors’ own first-hand, insider admission experienceand families may do so because they are dissatisfiedat colleges and universities nationwide. According towith school-based college counseling or because theythe latest financial information obtained, IvyWise anddesire a “leg up” compared to their peers. StudentsCollege Coach recorded net sales of 440,000 (Dunwho seek private college counseling are found moreand Bradstreet 2009) and 2.5– 5.0 million (USlikely to exhibit the following traits: 1) active adviceBusiness Directory 2008), respectively.seekers, 2) from privileged families, 3) apply to morecolleges, 4) attend private colleges far from home,A recent article in Inside Higher Ed questionedand 5) are less influenced by financial concerns (Mc-the ethics of private admission counseling (JaschikDonough, Korn and Yamasaki 1997).2008). According to the online news report, it isnot altogether out of the ordinary for full-time highMcDonough, Korn and Yamasaki’s (1997) finding thatschool college counselors or higher educationsocioeconomic status is a prevailing indicator for theadmission personnel to offer private consultinguse of a private college counselor has serious impli-services despite their day jobs. Such practices raisecations for college access. The authors point out thatconflict of interest flags and bring to light questionsless advantaged students, particularly first-generationabout whose best interests are these employeescollege students, are further disadvantaged becauserepresenting—students and institutions or their ownthose who already have the college-going resources,financial benefit? Although multiple relationshipsinformation and cultural capital end up accumulat-are not forbidden, the Independent Educationaling more of these things. The findings in this studyConsultants Association (IECA) and the Nationalalso appear to further attest to the phenomenon ofAssociation for College Admission Counselingstudents socially constructed as college applicants,(NACAC) offer statements of principles of goodwhich has fueled the growth of the entrepreneurial ad-practice that members are required to adhere to inmission sector (McDonough 1994). That is, studentstheir roles (IECA 2006, NACAC 2008b). For example,are no longer merely seniors looking to transition toNACAC stipulates that its members will “make pro-the next stage of their education. Rather, by engagingtecting the best interests of all students a primaryin the purchase of professional college knowledge,concern in the admission process” and “will be ethi-they can market themselves as competitive productscal and respectful in their counseling, recruiting andto higher education institutions, thereby transform-enrollment practices” (2008b, p. 2). IECA has a moreing themselves into college applicant commodities.explicit provision concerning “multiple relationshipsFurthermore, colleges and universities’ power-playsand potential conflicts of interest,” which its membersfor high-ability students seem to enable the managed“are expected to avoid” (2006, p. 1). However, notpackaging of applicants (Geiger 2002). Amidst theseall private admission counselors are members of thesedevelopments, an unfortunate consequence is thatassociations and therefore they are not all bound bystudents who do not have the means to game thethe same professional codes of conduct.system fall further behind.12 WINTER 2011 JOURNAL OF COLLEGE ADMISSIONW W W. N A C A CN E T.ORG

Mass Media Informational Resourcesthese rankings provide the public with relevant college informa-An area of the entrepreneurial admission sector that is availabletion, according to Mel Elfin, former executive editor of USNWR’sto more than the privileged few is mass media informational re-“America's Best Colleges,” the goal in creating the guide was tosources. The resources may include college guidebooks, such as“sell magazines” (personal communication, Spring 2002).Peterson’s Four Year Colleges and Barron’s Profiles of AmericanColleges. These companies also offer easily searchable CD-ROMPerhaps owing to the decentralized and hierarchical nature ofand online versions of their college manuals. Peterson’s and Bar-our higher education system, colleges and universities have aron’s are two long-standing, comprehensive handbooks, but thepropensity to chase after their more prestigious peers in thefield is littered with hundreds of college guides and advice books.name of reputational excellence (Astin 1985). Subsequently,A small sample of these include IvyWise founder Katherine Cohen’smass media informational resources attempt to communicate anThe Truth About Getting In and Rock Hard Apps, as well as Collegeinstitution’s reputation to the public, usually in the form of collegeCoach founder Michael London’s and Stephen Kramer’s The Newrankings in a variety of niches (e.g., academics, campus socialRules of College Admissions. Businesses that provide test preplife, selectivity, financial value, etc.). Research studying the impactservices, such as Princeton Review and Kaplan, also offer theirof college rankings has generally focused on the annual USNWRown versions of college guides and pursue aggressive marketingrankings (Clarke 2007, Ehrenberg 2002, McDonough, et al., 1998,tactics by embedding their test prep services with an abundanceMeredith 2004). In a review of the impact of higher education rank-of advertising for college promotional materials, including offersings on student access, choice and opportunity in the US, Clarkefor financial aid (Buckleitner 2006).(2007) notes that rankings have a tendency to help increasinglystratify the American higher education system. Ehrenberg (2002)Aside from the plethora of publications, mass media information-concurs that rankings drive schools into a high stakes, “academical resources are perhaps best embodied by national institutionalexcellence” social climbing game that does not accurately reflectrankings. The most prominent of these is U.S. News & Worldtrue academic quality, creates a needlessly competitive environ-Report’s (USNWR) annual “America’s Best Colleges” issue,ment and is counterproductive to educational priority.which offers a multitude of categorical rankings. On an international scale, rankings are also available from the British TimesIn terms of student consequences, Clarke (2007) concludesHigher Education world university rankings and China’s academicthat rankings “create unequal opportunities for different groupsranking of world universities, published by Shanghai Jiao Tongof students” (p. 66). She notes that rankings have a tendency rankings have a tendency to help increasingly stratify the American highereducation system rankings drive schools into a high stakes, “academicexcellence” social climbing game that does not accurately reflect trueacademic quality, creates a needlessly competitive environment, and iscounterproductive to educational priority.University. Rankings have certainly engendered their fair share ofto advantage high-income, high-achieving students most, ascontroversy, academic disdain, debates on admission outcomes,well as disadvantage minority and low-income students most.and institutional envy (Ehrenberg 2002, Meredith 2004). TheyMcDonough, et al. (1998) argue that the façade of rankings as ahave also been mainstreamed into our consumer culture (Chang“democratization of college knowledge” crumbles under the weightand Osborn, 2005). For example, Chang and Osborn (2005)of privatization and commoditization. In the study’s witheringexamine the USNWR rankings from the perspective of a “specta-discussion section, the authors lambaste the rankings industrialcle,” arguing that the abstracted images of rankings “have comecomplex and contend, “In fact, given that rankings users are high-to acquire a powerful role in determining the material conditionsSES, high-ability students, this phenomenon is likely contributingof colleges and universities” (p. 342). While it can be argued thatto social reproduction in college access” (p. 523).WWW.NACACNE T.ORGWINTER 2011 JOURNAL OF COLLEGE ADMISSION 13

Unlike federalloans, however,private loanspossess greaterflexibility interms of fees,interest ratesand repaymentterms; are riskierand thereforegenerally havehigher interestrates; andoffer greaterservices andrewards suchas an easierapplicationprocess andbenefits for ontime payments.An Expanding Sectorsophisticated financial tools and products toThe test prep industry, private college counsel-higher education institutions (SallieMae 2009).ing and mass media resources, such as nationalFurthermore, Nelnet owns CUnet, an enrollmentrankings, have been the most frequently examinedmanagement service provider, as well as Peterson’s,areas of the entrepreneurial admission sector. Thewhich, in addition to guidebooks, also offers test prep-main critique of these services is that they tendaration and student financial services. The breadth ofto further privilege students from already advan-products that SLM Corporation and Nelnet, Inc., astaged backgrounds and to excessively amplifywell as Kaplan (a subsidiary of The Washington Postthe competitive atmosphere of college admission.Company) and Sylvan Learning (owned by EducateAs a field for analysis, there are three additionalServices, Inc.) encompass suggests that a significantsegments of the entrepreneurial admissions sec-portion of the entrepreneurial admission sector istor—student financial services, college tours anddriven by a handful of large conglomerates.essay coaching—that researchers ought to consider and study more closely in terms of their impactThe concern about the high price of higher educa-on college access.tion is a common refrain that seems to echo amongstudents, families, the media, policymakers, andStudent Financial Servicespoliticians (Johnstone 2001). As the perception ofThe student financial services sector is a multi-higher education shifted from that of a public goodbillion dollar industry that generally involves savingsto a private good in the late 20th Century (Hellerand loan products. Though financial aid may be aand Rogers 2006), so too did the responsibility oflarge component of the business, the companiespaying for it transfer from institutions to individualsinvolved in these transactions may also engage in(Hossler 2006). Over the last couple of decades,other activities. According to the National Asso-students and families have increasingly turned tociation of College and University Business Officersloans as a means of funding their higher education(NACUBO), on the one hand there are not-for-profit(Long and Riley 2007). According to the Collegelenders and state-based student loan secondaryBoard’s Trends in Student Aid reports, although themarket organizations. On the other hand there arebulk of loans are federally awarded ( 72.9 billion inthe non-traditional lenders, such as Sallie Mae and2007–08), private sector loans were a 22.3 billionNelnet (2008). These two financial giants, known atmarket in 2007–08, an increase of 792 percentthe corporate parent level as SLM Corporation andover the private loan volume in 1997–1998 ( 2.5Nelnet, Inc., are publicly traded on the New Yorkbillion). By contrast, federal loan volume increasedStock Exchange (NYSE). In December 2008, SLMa mere 85 percent over that same decade fromand Nelnet reported gross operating profits of 5.5 39.3 billion (Baum and Payea 2008, p. 6, Baum,billion and 1.1 billion respectively (MorningstarPayea and Steele 2009, p. 6). Evidently, the private2009a, 2009b). Combined, these two conglomer-loan sector is a rapid growth market.2ates also own a host of subsidiaries with stakes invirtually every domain of the entrepreneurial admis-Lenders such as Nelnet and Sallie Mae, or tradition-sion sector. For example, in addition to managingal banks such as Bank of America or Citibank, may 180 billion in education loans, SLM also managesparticipate in both the federal loan programs andmore than 17.5 billion in 529 savings plans throughthe private loan market. As a result, private loansits Upromise, Inc. subsidiary, and the companyshare some similarities with federal loans, such asoffers a range of debt management services andthe stipulation that the loan amount cannot exceedDue to the economic recession and difficulties in the credit market, the 2009 Trends in Student Aid report estimates that private loan volume may be downas much as 50 percent in 2008–2009 compared to the previous year.214 WINTER 2011 JOURNAL OF COLLEGE ADMISSIONW W W. N A C A CN E T.ORG

the cost of attendance. Unlike federal loans, however, privateCE Tours provides one-stop shopping for teachers, counselors,loans possess greater flexibility in terms of fees, interest rates andparents, and students to arrange campus visits. In the samplerepayment terms; are riskier and therefore generally have high-four-day daily itinerary for California, the 17 schools toured orer interest rates; and offer greater services and rewards such asfeatured as alternatives reflect a range of public and privatean easier application process and benefits for on-time paymentscolleges and universities.3 For the most part, the undergraduate(Wegmann, Cunningham and Merisotis 2003). Given the seem-profiles of these schools fall in the selective or more selectiveingly ever escalating costs associated with attending college, thecategories of the Carnegie Classification system. Offering aboutstudent financial services sector will remain a big entrepreneurial20 tours per year, the College Visits tours range in price fromplayer in college access. 1,335 to 2,385 depending upon the region and time of year.Most of the schools listed on its 2009 tour schedules also appearThe topic of higher education finance is complex to navigate andto be selective or more selective schools.studies have shown that concerns about costs and perceptionsabout financial aid are deterrents to higher education participationCampus tours are rituals that enable institutions to constructfor low-income and racially underrepresented students (Free-an idealized image of the campus and its community (Magoldaman 1997, Luna De La Rosa 2006, Perna 2000). McDonough2000). Students who participate in a campus tour may be ableand Calderone (2006) call for more research that incorporatesto gain insight into the norms and values about an institutiona sociocultural understanding of money, costs, affordability, andthat cannot be gleaned from its Web site or printed materials.financial aid. In addition to the student and family point of view,Whether students visit campuses as part of a company’s pack-they state it is imperative that colleges also take into account theaged tour or on their own, they are incurring additional costs associocultural perspectives of the counselors and financial aid of-part of the admission process. In their role as socially construct-ficers who work with the individuals. In this way, institutions woulded college applicants (McDonough 1994), students are buyingbe better equipped to “adequately market college affordability”added knowledge about the schools, as well as selling their in-and therefore, work more productively towards “closing the col-terest to the admission offices. In a 2005 NACAC survey, 46lege access opportunity gap” (p. 1716). Given the enormity ofpercent of colleges reported that a campus visit by a prospectivethe student financial services sector, future research should alsostudent was considered a “plus factor” in the admission processexamine how the ent

The Commission of a 2008 National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC) report ar-gues that the consequent test prep industry "would not, of course, exist without two primary inputs: (1) a majority of colleges and universities require standard - ized admission tests for admission, and (2) families