Transcription

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov.18392000Robotics for Law Enforcement:Beyond ExplosiveOrdnanceDisposalH. G. NguyenJ. P. BottApproved for public release;distribution is unlimited.SSC San Diego0303003T'"

iii!!lIIIlIIII!I!!

III!III/% 4#TECHNICAL REPORT 1839November 2000Robotics for Law Enforcement:Beyond Explosive OrdnanceDisposalH. G. NguyenJ. R BottIIiIIIIiIII1PROPERTY OFNational CriminalJustice ReferenceService (NCJRS)Box 6000r4ocKvlie, MD 20849-6000Approved for public release;distribution is unlimited.@SPA WARSystems CenterSan D/egoSSC San DiegoSan Diego, CA 92152-5001

IiSSC SAN DIEGOSan Diego, California 92152-5001Ernest L. Valdes, CAPT, USNCommanding OfficerR. C. KolbExecutive DirectorI! ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATIONThe work described in this report was performed for the National Institute of Justice's Office ofScience and Technology by the SSC San Diego Adaptive Systems Branch (D371).Released byR. T. Laird, HeadAdaptive Systems BranchUnder authority ofC. D. Metz, HeadAdvanced SystemsDivisionDISCLAIMERWith respect to information provided in this document, neither the United States Government norany of its employees make any warranty, expressed or implied, including but not limited to the warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. Further, neither the United States Government nor any of its employees assume any legal liability for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product or process disclosed.Reference herein to any specific commercial products, processes, or services by trade name,trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement orrecommendation of the United States Government.!i III!lggSBiaa

IIIIi,IiIIIIIIIIIIIIEXECUTIVE SUMMARYMobile robotics has matured quickly in the past decade, with more and more robots enteringpractical field service. The two most active application areas for mobile robots so far have beenmilitary and law enforcement. For law enforcement, most activities to date have been in the area ofexplosive ordnance disposal (EOD), where robots are used to keep the human bomb disposal expertout of harm's way. In 1999, the National Institute of Justice (N/J) funded the Battelle MemorialInstitute to perform a survey on the desired attributes of an EOD robot. In addition, NIJ funded theSpace and Naval Warfare Systems Center, San Diego (SSC San Diego), to assess law-enforcementneeds for robots beyond EOD and identify technologies from Department of Defense (DoD) roboticsprojects that can help meet those needs.To establish law-enforcement needs for non-EOD robots, we conducted a web-based survey over aperiod of 8 weeks, hosted on our SSC San Diego Robotics web site. The survey addressed scenariosand tasks where a robot would be used if available, and the tools, features, and parameters deemedmost important to carry out those tasks. It also solicited respondents' experiences with currentlyavailable robots. The survey was publicized by electronic mail to over 200 state and local lawenforcement agencies.To identify DoD robotics technologies that could contribute to the development of lawenforcement robots, we conducted face-to-face, telephone, and e-mail interviews with personnelfrom the Unmanned Ground Vehicles/Systems Joint Project Office (UGVS/JPO) and the DefenseAdvanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). With leads from these funding and programmanagement agencies, we contacted various DoD robotics research and development activities andtheir contractors.We presented results from the two surveys. In particular, we found that the law-enforcementcommunity placed the most emphasis on having robots perform the functions of small-item delivery,passive remote communication, and remote surveillance. Features of a robot that were viewed asmost important include stair-climbing ability, a robust communication link, low cost, and longerbattery life. Most of these requirements are being addressed by the DoD activities surveyed.Solutions for other requirements can be found in the commercial sector or are being sought by thescientific community for applications outside robotics.We concluded that there would be no single robot that would meet all the demands of lawenforcement beyond EOD, and recommended the development of two classes of robots, separated bysize. Each robot should be modular, with application-specific mission packages or tool sets that canbe tailored to the needs of a specific user. We also outlined a proven, user-centric, phased, rapidprototyping approach for a successful robotics development program. Finally, we recommended thatNIJ personnel continue to maintain close liaison with DARPA and the Joint Robotics Program (JRP),and obtain input from JRP in the technology assessment, source selection, and development ofrobotics assets.iii

, [lHIt

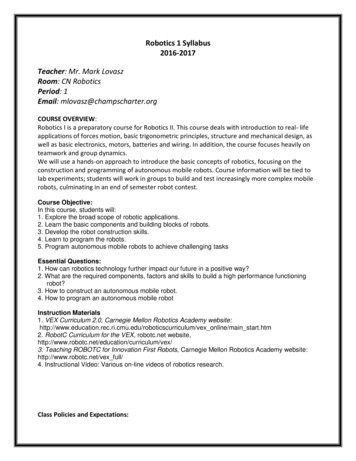

CONTENTS1. B A C K G R O U N D .2. L A W - E N F O R C E M E N T1N E E D S . 32.1 S U R V E Y P R O C E D U R E . 32.2 S U R V E Y R E S U L T S .32.2.1 S p e c i a l t i e s .42.2.2 Robotics E x p e r i e n c e .52.2.3 S c e n a r i o s .52.2.4 T a s k s .62.2.5 T o o l s .102.2.6 F e a t u r e s .112.2.7 Mobility .162.2.8 G e n e r a l F e a t u r e s .162.2.9 Past E x p e r i e n c e .202.2.10 G e n e r a l Interests .202.3 D I F F E R E N T I A T I O N BY R O B O T I C S E X P E R I E N C E . 203. D E P A R T M E N T O F D E F E N S E E F F O R T S . 233.1 J O I N T R O B O T I C S P R O G R A M ( J R P ) . 233.2 U G V / S J P O . 233.2.13.2.23.2.33.2.4M a n - P o r t a b l e Robotic S y s t e m ( M P R S ) .23S P I K E .25M A T I L D A .26O t h e r R o b o t - M o u n t e d W e a p o n s and T o o l s . 273.3 D E F E N S E A D V A N C E D R E S E A R C H P R O J E C T S A G E N C Y ( D A R P A ) . 283.3.1 T a c t i c a l M o b i l e Robotics (TMR) .283.3.2 Distributed Robotics (DR) . . . .303.3.3 Micro U n a t t e n d e d Mobility S y s t e m ( M U M S II) . 304. C O R R E L A T I O N B E T W E E N L A W - E N F O R C E M E N T5. R E C O M M E N D A T I O NN E E D S a n d D o D E F F O R T S . 31.336. R E F E R E N C E S .35APPENDICESA: S U R V E Y Q U E S T I O N N A I R E .B: T A B U L A T E D R E S U L T S , E N T I R E D A T A S E T .C: T A B U L A T E D R E S U L T S , R E S P O N D E N T S R E P O R T I N G P R I O R R O B O T I C SE X P E R I E N C E .D: T A B U L A T E D R E S U L T S , R E S P O N D E N T S R E P O R T I N G N O R O B O T I C SE X P E R I E N C E .A-1B-IC-ID-1

.35.36.37.38.39.40.41.42.43.Geographic orgin of survey responses .4Specialties of respondents .4Robotics experience among respondents .5Frequency of robot use (if available) in various scenarios . 6Explosive breaching .7Shattering windows .7Opening doors .7Observation/visual surveillance .8Listening/audio surveillance .8Delivery of small items .8Passive remote communication (by speaker and microphone) . 9Delivering chemical agents .9Retrieving small objects .9Robot-mounted weapons .10Video cameras .10Other sensors and effectors .11Maximum and most useful speeds . 11Most appropriate weight .12Most appropriate size .12Maximum reach .13Operating/stand-off distance .13Mission duration .13Manipulator lift capability .14Reasonable procurement cost .14Reasonable initial training time .15Reasonable maintenance time per month . 15Reasonable annual maintenance cost. excluding in-house labor . 15Importance of being able to traverse various outdoor terrain . 16Importance of being able to traverse various indoor terrain features . 17Importance of various communication links . 17Importance of various video interfaces . 18Importance of various self-defense mechanisms . 18Importance of various advanced features . 19Importance of various standard features . 19Law-enforcement interests in various types of mobile robots . 20URBOT (MPRS) with operator control equipment . 24SPIKE robot .25MATILDA robot (left) and MATILDA with breaching mechanism (right) . 26S A R G E robot with Foster-Miller less-lethal weapon launcher . 27Mini-Flail .28Lemming robot with less-lethal weapon launcher (left) and breaching saw (right) . 29SAIC's SuBot .29Scout robot .30Tables1. Correlation between law-enforcement needs and DoD effortsvi. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .311,1IIiII!iIIiI!II!

IIImiIi,' iIIIiiIiIII1. BACKGROUNDMobile robotics has matured quickly in the past decade, with more and more robots enteringpractical field service. The two most active application areas for mobile robots so far have beenmilitary and law enforcement. For law enforcement, most robotic activities to date have been in thearea of explosive ordnance disposal (EOD), where robots are used to keep the human bomb disposalexpert out of harm's way. In 1999, the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) funded the BattelleMemorial Institute to perform a survey on the desired attributes of an EOD robot (reference 1). Inaddition, NIJ funded the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center, San Diego (SSC San Diego), toassess law-enforcement needs for robots beyond EOD and identify technologies from Department ofDefense robotics projects that can help meet those needs. This report presents the results.

IImJ!1iil ilII111iiIIIB11

2. LAW-ENFORCEMENT NEEDS2.1 SURVEY PROCEDURETo establish law-enforcement needs for non-EOD robots, we developed a questionnaire in earlyMay 2000. We then met with members of the Los Angeles Sheriff Department's SpecialEnforcement Bureau (LASD-SEB) to discuss this questionnaire. From the feedback we received, wedecided to convert this questionnaire into a web-based survey. Participants used radio buttons andcheck boxes to answer most questions, which helped the response process.We let the web-based survey run for 8 weeks, hosted on our SSC San Diego Robotics web site(reference 2). The survey was publicized by electronic mail to over 200 state and local lawenforcement agencies whose e-mail addresses were found at various law-enforcement web sites(references 3 through 6). The National Tactical Officers Association also posted a link to our surveyon their web site (reference 7).Responses were converted to text messages by a Perl-script program residing on the web serverand were forwarded to another computer for storage. When the survey was completed, a C programcombed through the stored messages, tallied up the responses to each question and generatedsummary tables. These tables were then entered into an Excel spreadsheet, which generated thecharts in this report. The individual messages were also printed out and examined to extract manuallyentered information (from the "other information" or "notes" and "comments" fields), and to gaininsight into unusual answers or unexpected groupings.The survey has five parts. Part 1 establishes the respondent's background. We were interested inknowing how a respondent's familiarity with law-enforcement robots correlates with the actualresponses. This hopefully will help us separate long-term desires and goals from more practical,short-term needs as would be reflected in the responses from those with more experience with robots.Part 2 examines scenarios where robots would be used, the tasks they would perform, and the toolsrequired to accomplish those tasks. Part 3 discusses the features and parameters considered importanton the corresponding robots, and part 4 solicits experiences with currently available robots. Part 5asks a short question to establish the law-enforcement community's interests in various types ofmobile robots.2.2 SURVEY RESULTSWe received 65 responses from our web survey. Some were direct responses from lawenforcement agencies to our e-mail solicitations, others were from law-enforcement officers whofound links to our survey at various web sites. Figure 1 shows the geographic origin of the responsessuperimposed on a U.S. population density map.I,II3

IIIIiFigure 1. Geographic origin of survey responses.Below is a summary of survey answers presented as charts to help visualize comparativesignificance. Appendix B contains the tabulated results, excluding personal information.2.2.1SpecialtiesAlmost half of the respondents were members of the tactical community. Figure 2 shows the specialties indicated on the survey returns.IIIiIiSWATBomb disposalK-9Narcotic/GangINegotiatorTechnology evaluatorAdministratorI Other05101520Number of responsesFigure 2. Specialties of respondents.42530IIIII

2.2.2 Robotics ExperienceFigure 3 summarizes the respondents' experience with robots. Over 50% of the respondents had noexperience with robotics. No respondent reported having a non-EOD robot only.fIII II11' 1111111No experienceHave looked into obtaining a robotHave used a robot in the pastCurrently have an EOD robot, looking for another robotCurrently have a non-EOD robot, looking for another robotIICurrently have both types, looking for another robotimRobotics needs are currently met0510152025303540Number of responsesFigure 3. Robotics experience among respondents.2.2.3 ScenariosInspection of hazardous areas and dealing with barricaded suspects ranked highest on the list ofscenarios where a robot would be used if available. Serving high-risk warrants, identified during theinitial meeting with LASD-SEB, was not considered appropriate for robotics by most respondents.Figure 4 rates the four scenarios provided in the survey questionnaire. The horizontal axis compartmentalizes the percentages of the missions when a robot would be used if available, and the verticalaxis represents the number of survey responses picking those percentages.Other scenarios that were mentioned included (each by one respondent):9 Reconnaissance in tunnels and storm drains (at U.S. ports of entry)9 Searching for criminals and lost persons9 Acting as hilltop repeater9 Site security9 Public reception and information dispenser9 Remote supervision9 Act as hostile element in training9 Dealing with suicidal subjects

Ii740"I"'l-"tF30135r0Q.o "" "25-"6 20!ir,. ,:.0Ez10"t j, o 2 f / High-risk warrants/" Inspection of harzardous areasL0-20%20-4O%Barricaded s us pectsffJHostage40-60%rescue60-80%Percentage of missions8O-lOO%Figure 4. Frequency of robot use (if available) in various scenarios.2.2.4 TasksTwo questions were posed regarding the importance of various tasks a robot could be asked toperform. The first question queried the percentage of times a certain task is performed (by anymethod), and the second question determined the percentage of the times that the task is performedwhen it would be performed by a robot, if available. The role of the first question is to clarify thesecond question for the survey respondent. The importance of robots to the task is primarilydetermined by the answers to the second question. This is analogous to the importance of theaccuracy of a firearm. It does not matter if firing a weapon only takes place during a minisculepercentage of the missions, the accuracy of the shots when they are fired is still very important.Figures 5 to 13 summarize the results, with the percentage of times a task would be performed duringthe above missions listed on the horizontal axis. The vertical axis represents the number of responses.We can see from these graphs that the tasks most demanded by respondents for robotics supportare delivery of small items (wireless telephones, food, etc.) and passive remote communication(where the target person is not required to cooperate by using a telephone). These are followed byvideo/audio surveillance and retrieval of small objects.Other tasks mentioned (by one respondent each) include:o Creating a diversiono Providing zone defenses, alerting units when suspects are movingo Identification of subjects and weaponso Valve manipulationo Retrieving injured officer or hostage from hostile environment6IIiIiIIIlIiIIIi,!!

(/}O)0Q.tIE",lZu" u-/ 20-40 EIX o: ;;br,0,0%60-80%::::"ng:,robots80-100%Figure 5. Explosive breaching.IIIIIi1III,IIIi257(nJ200U) 15"6 10E- !!5ZC2040% , . ,;40.60 . j -- 60-80%Shatteringwindowshatteringwindowsby robots80-100%Figure 6. Shattering windows.rd}cO0."6.QE'-'1ZOpening doors)ening doors by robots60-80%80-100%Figure 7. Opening doors.

30 rj 25cOCL2(]15"61(.QE, Z/ robots60-80%80-100%Figure 8. Observation/visual surveillance.2"-"IIIIiIIu)0c"0Q.EZListening tening by robots60-80%80-100%Figure 9. Listening/audio surveillance.IIII25 !(/]OC00.2015"5EZ1053elivery of small items, livery by robots60-60%80-100%Figure 10. Delivery of small items.IIII!!!

!,!ii2II.iIPassiveremotecomm.Passivecomm.by robots90 20% 20-40%40-60% 60 80%80-100%Figure 1 1. Passive remote communication (by speaker and microphone).: 0 i L L 0-20% 20-40% I . '. / Deliveringchemicals tnega / Deliv.chem.agentsby robots60.60% 80-100%Figure 12. Delivering chemical agents.,.1301 "'''' j20 j"6!jI.QEzt0-20% 20-40% 4o-6o% 60-80% 80-100%- 7 Retrievingsmall objects//Retrieving ooje ;ts by robotsFigure 13. Retrieving small objects.

2.2.5 ToolsFigures 14 to 16 show the perceived usefulness of various robot-mounted tools. The frequency thateach tool would be used, if available, is listed on the horizontal axis. The vertical axis represents therespondents' selections. The respondents placed emphasis on sensors and effectors, while robotmounted weapons were not viewed as important. Types of less-lethal weapons mentioned includebeanbag rounds, sage rounds, pepper spray, sting balls, nets, TASER and pulse lighting.4035300Q.2520 Ee loly ::Zlethal weaponse launcher0-20( 60-80%80-100%Figure 14. Robot-mounted weapons.25 " J " ' q " . . . . . . .C/)tO13.(/)o20 " J15 i-10EZiiIIIIIiIiIii!5 840 Infrared/low-lightvideo cameratylightvideo camera(60 0%80-100%Figure 15. Video cameras.10IIII!

0-20% 20-,40% 40-60%IRemote speakerand microphone60-80% 80-100%Figure 16. Other sensors and effectors.IIIIIOne or more respondents also indicated that law-enforcement robots could use the following tools:9Tire-deflating strips9Chemical/biological agent sensors9GPS/dead-reckoning locating9Laser range finder9Window punch for automobiles2.2.6 FeaturesThe next group of graphs summarizes the responses on the most reasonable or appropriate values forvarious features of a robot that would best meet the respondents' needs.I 0II' L 2-3 - /Maximum speed:-- - j ost use,u, spee,O-/4 4mphFigure 17. Maximum and most useful speeds.iII.t11

While most respondents chose a maximum speed of 2 to 4 miles per hour, the most useful speedwas pegged at around 2 miles per hour.IiI(n09tOCLIII201509.o.oE'-'1105ZC75-100Ibs.I 100lFigure 18. Most appropriate weight. .-- IIII i:. .40 84(/] 35t-09O30o. 25I09-6 20 E Z.Q1510(during transport)5(24-3636-48 48"iIinchesFigure 19. Most appropriate size.The composite most appropriate size for the robot is a rectangular box, 24 to 36" long, 12 to 24"wide, 24 to 36" high (stowed), and weighing 50 to 75 pounds. There is demand for robots smallerthan this, but almost no demand for robots larger than 4 feet on each side.12IiII

t0-22-44-55-6 6ft.Figure 20. Maximum reach.3 20 "615.o10z-1 .-5J""":0-5050-100100-200ft.200-500 500Figure 21. Operating/stand-off distance.1 as 0Q. 3025"020 .Q15E10Z5001122-33 "hoursFigure 22. Mission duration.13 4J

IThe question on mission duration was not optimally designed. As a result, we know that thedesired operational duration is over 4 hours, but we do not have an upper bound.Ii, , .--:. . . . . . . . .30 :t(/) 25(DEoo20ffl-i"6f10E!Z0-55-1010-2020-40Ibs. 40JFigure 23. Manipulator lift capability.The responses to this question were somewhat bimodal. There was desire for robots withmaximum lift capability at around 20 pounds and at over 40 pounds.oe-o"6::i lIII,IIIIf0% .o ,-v y, 65-100 100Ithousand dollarsFigure 24. Reasonable procurement cost.A clear majority of the responses picked a reasonable procurement cost of under 40K. Thisreflects the limited budgets faced by most local law-enforcement agencies, as singled-out separatelyby several survey participants.lIIi!14!

30 09u 25tOiiil 2oO, .:-., Er . : o. DZ1-2 hrs2-8 hrs 2-3 days 3-5 days 5 daysFigure 25. Reasonable initial training time.o 20"615 fZ,I /, i ilJ 0-1" "i.1-24-8 8hoursFigure 26. Reasonable maintenance time per month.o15, [-' "6Zooooo.,oo1K-2Kdollars 2KFigure 27. Reasonable annual maintenance cost, excluding in-house labor.15

I2.2.7 MobilityIFigure 28 summarizes the perceived importance of the robot being able to traverse certain outdoorterrain. On the horizontal axis, 4 is most important, 0 is least important. The number of responses isgiven on the vertical axis for each terrain. From this figure, we can see a heavy emphasis on beingable to traverse over curbs, bumpy dirt, and high grass, followed by mud, snow, and rubble. Sandreceived the least emphasis.lilt9mIIIi -2o. . . . . . .Rubble i- ":.!'-,"'-15sb r uCO- l9Mud & s n o""' 'IB u m p y dirt0123HighLowFigure 28. ImportanceamBof being able to traversevariousoutdoor terrain.Figure 29 provides similar responses to various indoor terrain features. We see a unique emphasison the ability to traverse stairs, followed by the capability of travelling over loose rugs andnewspapers, and not getting entangled in telephone wires and cables. Though not as strong as thepreviously mentioned categories, the ability to go under crawlspaces was also considered important.One survey participant also added the capability to operate in an airplane or bus aisle.2.2.8 GeneralFeaturesFigure 30 shows the perceived importance of various remote control and communication links. Aradio frequency (RF) link was considered most important, followed by a dual-RF/optical-fiber link,with optical fiber alone last.Figure 31 confirms the importance of having a large viewing screen at the command post and atactical handheld viewfinder that the robot operator can use either in full sunlight or inconspicuouslyin darkness.Figure 32 shows the perceived importance of some self-defense mechanisms. An armored bodyand hidden deactivation switch were judged more critical than keep-away defensive mechanisms(tear gas, electric shocks, etc.), although all three were considered important.16IIIIIIlII

Iii!I,!I,zt 3t:roo0t/iStairsRugs/newspapeWires/cCra 1oi LoW,I!IIIi!Figure 29. Importance of being able to traverse various indoor terrain features.4540cO353025"6 20E15Z105sDual linkptical fiberink4LowHighFigure 30. Importance of various communication links.I!I!17

1iI!401(9(/)t'0Q.(/)35-:3025"5 2015E 105z0e Large view screenandhetd viewfinder3Low4i!!HighFigure 31. Importance of various video interfaces.30i.I!25r0Q.Ct}2015Ez1C Hidden switch efensivemechanismslored body(3LowHighFigure 32. importance of various self-defense mechanisms.Figure 33 covers more advanced features. Self-righting topped the list, followed by backpackability and semi-autonomy. The ability to operate several robots concurrently did not receivemany votes, although the few that voted for it mentioned possible use in scenarios involving largebuildings, with one robot acting as a strategically placed sensor and another performing specifictasks.The more obviously desirable features (weatherproof, ruggedness, modularity, and use of standardpower sources) were endorsed by most responden

available robots. The survey was publicized by electronic mail to over 200 state and local law enforcement agencies. To identify DoD robotics technologies that could contribute to the development of law- enforcement robots, we conducted face-to-face, telephone, and e-mail interviews with personnel