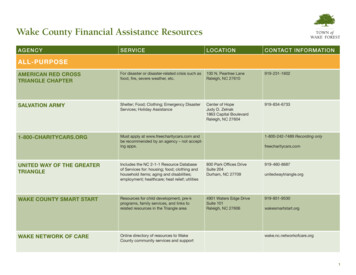

Transcription

the wake county affordable housing project Thomas Barrie, AIAisbn 978-0-9776635-6-9 published by the college of design, north carolina state university 2010NC STATE UNIVERSITYCOLLEGE OF DESIGNthe wake countyaffordable housing projectThomas Barrie, AIA

the wake countyaffordable housing projectThomas Barrie, AIAThe School of Architecture NC State University College of DesignWake County Human Services Housing and Community Revitalization DivisionAn NC State University College of Design PublicationRaleigh, North Carolina2010i

NC State University College of DesignCampus Box 7701, Raleigh, North Carolina, 27695-7701design.ncsu.edu 2010 An NC State University College of Design PublicationISBN 978-0-9776635-6-9Thomas Barrie, AIAThe Wake County Affordable Housing ProjectProject research and coordination Katherine Ball (M.Arch 2009),Brielle Cordingly (M.Arch 2011) and Lauren Westmoreland (M.Arch 2011)Design and production by Liese Zahabi (MGD 2010)Thomas Barrie reserves all rights to this material in conjunction with theCollege of Design at NC State University.Unless otherwise stated, all photographs by Thomas Barrie.The Wake County Human Services Housing and Community Revitalization Divisionfunded the Wake County Affordable Housing Project.Printed in the U.S.A.200 copies of this public document were produced at a cost of 2,400, or 12 dollars per copy.iith e wa ke coun t y a f ford a b l e h ou s i n g p ro j e c t

table of contentsIntroduction. 1Project Description and Background. 2Project Goals and Process. 2Pilot Town Workshops. 8Service Learning Projects and NC State. 9Establishing the Contexts. 11Affordable Housing is Fair Housing.12A House is Not a Home — The Symbolism of Home.14Cultural Presumptions and Consumer Preferences —The Roots of the Suburban Single-Family House.16Transit-Oriented Development and Affordable Housing.21Sustainable Design and Affordability.24Identifying the Needs.27The Need for Affordable Housing in Wake County.28Providing Solutions.31Affordable Housing Strategies and Demonstration Projects.32Making It Happen. 49National Affordable Housing Precedents and Strategies.50Conclusion.59Appendix.63Project team.64About NC State, the College of Design and the School of Architecture.65iii

Twelve students participated in the semester-long design project. Left to right: Maria Papiez, Jeffrey Pleshek, Jessica Cochran, Erich Brunk,Thomas Barrie, AIA, Professor of Architecture, Keith Wales, Hariwan Zebari, Trey McBride, Geoffrey Diamond, Tyler Morrison and PatrickMadrigan. Not shown, Stephanie Greene and Lindsay Ottaway.acknowledgementsThis project was the result of a unique partnershipbetween the Wake County Human Services Housing and Community Revitalization Division and theSchool of Architecture at NC State University Collegeof Design. Community-based projects of this typeprovide special research and educational opportunities and depend on the sustained efforts of many.The following are those who gave their time andexpertise in ways that were essential to its success.First of all I would like to thank my students whosesustained and committed efforts throughout thesemester-long design project exceeded the requirements of the course. The Wake County HumanServices Housing and Community RevitalizationDivision provided the funding and thanks go toEmily Fischbein, AICP, Community DevelopmentSpecialist, who was instrumental in initiating theproject and guiding its process, and AnnemarieMaiorano, AICP, Housing Division Manager forarranging for the funding.The Pilot Town Workshops depended on the assistance and participation of many, but special thanksgo to the following:For the Cary Workshop: Mayor Harold Weinbrecht, Jr.,Planning Manager Phillip Smith, Senior Planner Juliet Andres, and Senior Planner Tracy Stone-Dino. Forthe Wake Forest Workshop: Mayor Vivian Jones andPlanning Director Chip Russell. And for the WendellWorkshop: Mayor J. Harold Broadwell, Town ManagerDavid Bone, and Planning Director Teresa Piner.ivth e wa ke coun t y a f ford a b l e h ou s i n g p ro j e c tOthers generously provided their time and expertiseduring the design and research phases of the project.Chris Estes, Executive Director of the North CarolinaHousing Coalition, conducted a seminar for thestudents and Carly Ruff, Policy and Outreach Coordinator, provided valuable resources for their research.Robin Abrams, Georgia Bizios, Emily Fischbein, RandyLanou, Annemarie Maiorano, Wendy Redfield, CarlyRuff, Kristen Schaffer, Paul Tesar, Sean Vance, andJim Zuiches served as design critics and providedvaluable input at critical points throughout thesemester. And sincere thanks to Graduate Architecture students Katherine Ball, Brielle Cordingly andLauren Westmoreland, who served as Research Assistants for the project, and to Graduate Graphic Designalum Liese Zahabi for the design of the publicationyou hold in your hands.The project is also an outcome of my College ofDesign Research, Extension and Engagementappointment in Affordable Housing and SustainableCommunities. A special thanks to Dr. Jim Zuiches,Vice Chancellor for the NC State Office of Research,Extension and Economic Development, forhis support.Thanks to all for our collective efforts to find answersto the housing and community-building challengeswe face, and for envisioning a sustainable future forWake County.Thomas Barrie, Professor of ArchitectureNC State University College of Design

introductioni n tr o d u c t i o n1

Project Description andBackgroundWake County is too-often characterized by placeless sprawland a lack of transportation and housing choices.The Wake County Affordable Housing Project was aresearch and design project conducted by faculty andstudents from the School of Architecture at NC StateUniversity College of Design. The project included research on housing needs in Wake County and nationalprograms and best practices in affordable housing,and the design of a range of affordable housing models. It focused on affordable housing strategies, with aparticular interest in transit-oriented development. Italso incorporated considerations of sustainable communities, which are defined as places that over timeare ecologically responsible, economically viable andsocially equitable.1 The project included a number ofdesign workshops conducted at designated Pilot Towns.Lastly it is hoped that the project outcomes will assistthe Housing and Community Revitalization Divisionof Wake County Human Services to provide affordablehousing in Wake County.Project GoalsThe overall goals of the project included the following:There is a significant amount of substandard housing inWake County, including overcrowded households and unitswithout plumbing and/or heating. Pictured: Manufacturedhouse in Holly Springs.Open country and farmland are part of what makes WakeCounty a beautiful and unique place. Unfortunately, thevery qualities that make Wake County special risk becomingplaceless sprawl. Pictured: Wendell farm for sale.2th e wa ke coun t y a f ford a b l e h ou s i n g p ro j e c t To provide the students with the enriched educational experience of a real-world project, as part oftheir education as future leaders in the profession. To provide The Wake County Human ServicesHousing and Community Revitalization Divisionwith national best practices and leading-edgestrategies and models for affordable housing inWake County, as a foundation for further researchand the professional design of future projects.

Project ProcessThe Wake County Affordable Housing Project was ayear-long research and design project that includeddirected research by research assistants and a semesterlong graduate design studio. The design studio wasconducted during the 2009 Fall Semester and includedgraduate and undergraduate students in architectureand landscape architecture. The studio began withphysical research on Wake County ex-urban towns andunincorporated areas (excluding Raleigh), includingCary, Morrisville, Apex, Holly Springs, Fuquay-Varina,Garner, Zebulon, Wendell, Wake Forest and Rolesville.For each locale, student teams provided documentationand analysis of their essential histories, physical characteristics, and housing types. There was particular attention paid to transit hubs, downtown area(s), walkableresidential neighborhoods, and housing types. Overall,the students aimed to incisively and evocatively qualifyand communicate the essential characteristics of theirstudy area.Traditional downtowns distinguish parts of Wake County.Picture: Downtown Apex.The research had a particular focus on housing types in Wake County. (Jessica Cochran and Lindsay Ottoway)i n tr o d u c t i o n3

4th e wa ke coun t y a f ford a b l e h ou s i n g p ro j e c t

The field research focused on downtown areas, existing andfuture public transportation, walkable residential neighborhoods, and housing. (Analysis of Apex by Trey McBride andHarawan Zebari)i n tr o d u c t i o n5

Cary’s downtown is centered on the intersection ofAcademy and Chatham streets.Following these initial surveys and analyses, three PilotTowns were designated for focused study. The towns —Cary, Wake Forest and Wendell — were chosen becauseof their unique qualities, the diversity each brought tothe study as a whole, and their willingness to participate. For each Pilot Town, student teams engaged infurther research on the physical characteristics of thebuilt environment, housing, existing or proposed transportation links and other issues germane to the project.Concurrently, the studio’s research assistant compileddemographic information on Wake County and bestpractices regarding the legislating, funding, and theprovision of affordable housing nation-wide, with aparticular focus on leading edge counties — all ofwhich was shared in review and de-briefing sessions.Furthermore, student teams produced precedentresearch on affordable housing best practices, including mixed-use and mixed income examples (see pages50–54 ).The small-town character of Wake Forest is accentuated byits traditional downtown.Residents of Wendell are justifiably proud of its historicdowntown.6th e wa ke coun t y a f ford a b l e h ou s i n g p ro j e c tThe Wake County Affordable Housing Project addressed affordable housingcontexts, issues and needs countywide, but with a particular focus on threedesigned Pilot Towns: Cary, Wake Forest and Wendell.

Following the research and analysis phase, studentsidentified potential sites, based on the following criteria: Proximity to existing or proposed public transportation link(s). Walkable to centers of businesses and services. Available land of sufficient size and configurationto accommodate multiple housing units and, ifappropriate, mixed-uses. The potential for new development to createmore cohesion and identity within the existingurban fabric. Correspondence with sites identified for futuredevelopment in current city studies or plans. Orientation and environmental conditions to facilitate sustainable development and architecture.Proximity to existing or proposed major transportationlink(s) within walking distance of businesses and serviceswere central to site selection. (Analysis of Wake Forest byJessica Cochran)Based, in part, on responses to the research on localand national contexts, the students next developedpreliminary site and building strategies for theirchosen sites. These were brought, along with theresearch, to the Pilot Town Workshops. Additionally,throughout the semester, interim reviews of studentdesign proposals were conducted during which stafffrom Wake County Human Services, local housing providers and advocates, and faculty provided input basedon their areas of expertise.Throughout the semester, interim reviews of student designproposals were conducted, during which staff from WakeCounty Human Services, local housing providers and advocates, and faculty provided input based on their areas ofexpertise. Pictured: Graduate student Maria Papiez receivesinput from (from left to right) Randy Lanou, Georgia Biziosand Emily Fischbein.i n tr o d u c t i o n7

The Cary Workshop was conducted at the historic Page Walker House andincluded presentations, input, discussion, and a walking tour of the downtown area.Pilot Town WorkshopsMayor Vivian Jones leads the tour of Wake Forest.Mayor Harold Broadwell speaks at the Wendell Workshop.8th e wa ke coun t y a f ford a b l e h ou s i n g p ro j e c tThe Pilot Town workshops were opportunities to present initial research findings and preliminary designproposals, and receive input from municipal leaders,housing providers and residents — all as a means toidentify predominant issues. Students and faculty benefitted from the perspectives of those who know theircommunities best, and the subsequent design development aimed to incorporate as much of the informationand advice as possible. Overall, students and facultyaimed to substantially incorporate local character andurban conditions while utilizing research on established strategies or emerging national trends in affordable housing.

Service Learning Projects and North CarolinaState UniversityNorth Carolina State University is NorthCarolina’s largest comprehensive university.Founded in 1887 as a land-grant institutionunder the Morrill Act of 1862, NC State has athree-part mission: instruction, research, andextension. The latter describes the uniquemodel of land-grant universities that werefounded following the Civil War. Congressdeeded land to establish new universities thatwould not only educate students but wouldserve their citizenry. This unique Americanmodel has the goal of accessible educationpaired with an extensive outreach andservice mission.Like other land grants, NC State began byserving the agricultural needs of the mostlyagrarian state through its schools of agriculture and veterinary medicine. Today all 100counties continue to be served through theCounty Extension program. As the state’sdemographics and industrial profile havechanged, however, so have the servicesprovided by NC State. Its broader servicemission now includes economic development,re-tooling industry, technology transfer, urbanaffairs, community services, housing and urban design. Where in the past a farmer mightcontact a County Extension Officer to seekanswers to a problem, now it is municipal andbusiness leaders who come for the expertisethat only a Research I institution can provide.faculty, issues such as environmental health,universal design, landscape urbanism,community art programs and the designof home environments are addressed.The Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities Initiative founded by Thomas Barriefocuses on research, community-baseddemonstration and service-learning projects,and the development and dissemination ofa knowledge base in its subject area.Its mission is primarily educational — to provide educational resources for government,non-profit and community leaders, studentsand the general public, and innovative andapplicable solutions to the housing and urbanchallenges that North Carolina communitiesface. Traditional research and applied researchthrough funded projects and service-learningstudios are potent means to produce substantive, applicable and measurable outcomes.The education of qualified practitioners andfuture leaders in the profession remainscentral to our mission, and therefore theintegration of professional education andresearch is essential.Increasingly NC State is serving more andmore cities, small towns and communities inareas of housing and urban design — most ofwhich is performed in the College of Design’sOffice of Research, Extension and Engagement.Through a diverse group of initiatives andi n tr o d u c t i o n9

10th e wa ke coun t y a f ford a b l e h ou s i n g p ro j e c t

establishing the contexts11

Affordable Housingis Fair HousingIt is a well-known fact that, for too-many Americans, the availability of safe, decent housing is outof reach, a national condition that has only worsened during the recent economic downturn. Oftenit is the most vulnerable of our fellow citizenswho are disproportionally affected — low-wageworkers and families with children. The term “fairhousing” has its origins in Title VII of the CivilRights Act of 1968, which prohibited discrimination in housing according to inclusive criteria.Today, though many states have adopted fairhousing regulations (including North Carolina), itrefers more generally to the social equity issuesgermane to accessible and affordable housing.Affordable housing is generally defined as homesfor individuals and families who cannot affordmarket rate in their communities and, specifically, as housing that costs less than 30 percentWell-planned and designed housing can aid in creating the character and sense of identity upon which the value of our communitiesare inextricably paired. (David Baker Partners, Architects, Armstrong Place, San Francisco)12th e wa ke coun t y a f ford a b l e h ou s i n g p ro j e c tof a household’s gross income. Affordable housing is often referred to as “work force housing” or“essential worker housing,” reflecting the fact thatlow-wage workers include those upon whom wedepend for basic community services — nurses,day-care providers, teachers, firemen and policemen. Others who need our help are also in themost precarious situations regarding housing:those with chronic illnesses or homelessness.Any measure of a culture depends on how well itsupports the full spectrum of its members. In thiscontext, the provision of affordable housing is anethical issue. It is simply the right thing to do.However, making sure that our community’shousing needs are addressed (and eventually met)not only supports our fellow citizens, but strengthens local economies and communities. For example, affordable housing is often misunderstood asproviding minimum shelter or taking the form oflarge projects, which often provokes worries aboutits effect on property values. However, current

research indicates that community-based affordable housing does not adversely affect propertyvalues. In fact, proactive housing programs canaddress issues such as sub-standard housing thatcan have substantial impacts on property values.Moreover, well-planned and designed housing canaid in creating the character and sense of identityupon which the value of our communities areinextricably paired. Providing housing where it isoften needed the most, close to commercial centers and transportation, is an effective antidote tothe ubiquitous sprawl that too-often characterizesour ex-urban municipalities. A range of affordablehousing types allows family members to trade upwithout moving out, and for the elderly to age inplace. Also, it is well known that “non-traditional”families comprise 75 percent of national demographics — households of unmarried individuals or couples without children, of whom manyprefer smaller units. It is this population that oftengravitates towards civic and commercial centersand who are an essential component regardingthe health of local economies. In the end it makeseconomic sense — decent, accessible, and affordable housing costs less in the long run and addsmuch to our communities.A House is Not a Home —The Symbolism of Homeworld, a cocoon where we can feel nurtured andlet down our guard.”2 The term “home” is oftenused to describe where we were born or raised,our “home town,” indicating its profound and enduring ontological significance. To speak of one’s“homeland” is to describe a unique place to whichwe are inextricably bound. As in J.H. Payne’s TheMaid of Milan (1832), “Be it ever so humble, there isno place like home.”While we typically refer to dwelling units as“housing,” what we all desire is a “home.” Homeis the center of our lives, the place that we maydepart from, but to which we always return. Asthe hub of our personal world; its safety andstability are essential to our sense of well-being. Ifour homes become precarious, whether throughthreats of foreclosure or eviction, unsafe neighborhoods or deteriorating conditions, our lives aresimilarly viewed or experienced as unstable andthreatened.As in the Burt Bacharach and Diane Warwick song,“A house is not a home, when there is no one thereto hold you tight,” we may rent or buy a house orhousing unit, but it is through our occupation andpersonalization that the house becomes our home.It is a place that we appropriate and where we express ourselves. As Dolores Hayden states, “A homefulfills many needs: a place of self expression, avessel of memories, a refuge from the outsideThe feeling of “being at home,” describes a condition of ease and comfort, and so it is not unusualthat we often tell our guests to make themselves“at home.” Dorothy, who in the Wizard of Oz soplaintively cried, “There’s no place like home!”echoed Homer who wrote in The Odyssey, “There’snothing better in this world” than a “happy peaceful home.” Odysseus is homeless for many yearsfollowing the Trojan Wars, unable through a rangeof circumstances to find his way home, poeticallydescribing the disorientation and terror of being“homeless.” Robert Frost in his evocative poem“The Death of the Hired Hand” writes that “homeis the place where, when you have to go there,e s ta b l i s h i n g t h e c o n tex t s13

they have to take you in.” How many times in ourlives when, feeling buffeted by events or challenges,have thought or cried, “I just want to go home!”Home is our refuge from the vicissitudes of theworld and thus its enduring symbolism as a placeof stability and safety. These perspectives and contexts are essential to the integration of all of theissues germane to housing in general and affordablehousing specifically.The feeling of “being at home,”describes a condition of easeand comfort. (Home images byJessica Cochran)Cultural Presumptions andConsumer Preferences —The Roots of the SuburbanSingle-Family HouseA significant challenge to advocating for andproviding housing that serves a broad spectrumof income levels and needs in our communities isthe cultural presumptions regarding the best formof housing. Over time North American culturecame to prejudice the single-family house at theexpense of other, more affordable models. Thosewho own single-family houses tend to hold the14th e wa ke coun t y a f ford a b l e h ou s i n g p ro j e c tview that any other model will adversely affectthe character and value of their community —and those who don’t tend to aspire to own one.And, even though multifamily housing is common in suburbia, it is often both physically (by itslocation in peripheral areas) and culturally “invisible.” It is essential to recognize the cultural foundations of these prevalent attitudes — as a means touncover the power they hold in both national andlocal debates regarding affordable housing. In particular, opposition to affordable housing, so-calledNIMBYism (Not In My Back Yard) often dependson unexamined attitudes that are predominantlycultural and emotional.

It is important to recognize the privileged positionthe single-family house has assumed in Americanculture. For individuals and families, the purchaseof a single-family house is often the most significant investment they will make in their lifetimes.It comprises most of their equity, serves as themeans to secure other loans, and is viewed as alife insurance policy or retirement account. Formunicipalities, property taxes comprise a significant portion of their tax base, (revenues that payfor public safety, schools and other essentialservices). For this reason speculative developersoften receive incentives from municipalitiesbecause of the capacity of new subdivisions toincrease the tax base. And, logically, the moreexpensive the houses, the more tax they generate,a further incentive to attract higher price point developments. Lastly, in a national context, supportof the single-family house comprises the largestpublic housing program in the country throughthe federal income tax deduction for mortgageinterest.3 (There is no comparable deduction forrent.) Indeed, homeownership is often presentedas an ideal, implicitly relegating renters to the status of second-class citizens. In these contexts, thedominance of the single family house is clear, andit is understandable why affordable housing ingeneral, and subsidized rental housing specifically,can appear to be so threatening and opposition toit often so visceral.It is obvious that there are other ways to own one’sdomicile beyond the single-family house, and thatrenting can give one the flexibility home ownership doesn’t. According to Paul Krugman, “thereare some real disadvantages to homeownership,”and he points out the following risks and limitations: in today’s market homes can precipitouslylose value; homeownership limits our ability tomove (to new jobs etc.); and single-family housesin the suburbs accrue significant transportationcosts.4 Why then, the almost myopic preference forthe single-family house? And, why the ubiquitoushome styles and imagery of most of our subdivisions? To answer these questions, we need to turnto 18th century England and the rise of the world’sfirst true middle class and the establishment of thefirst suburbs.Even though suburbs dominated by single-familyhouses may be the ultimate American culturalartifact, its genesis was in the industrial Englishcities of London and Manchester.5 Until the 18thcentury, ex-urban areas surrounding major citieswere seen as inferior, and to call someone a ‘suburbanite” was to insult them.6 The aristocracytraditionally lived in cities, but maintained countryestates or hunting lodges for their entertainment.However, with the rise of a new mercantile middleclass, attitudes about the city and its ex-urbanareas changed. For the first time in British society there was a class of wealthy people who hadachieved positions of power through their ownentrepreneurship and hard work. No longer wasthe ability to buy property and build one’s ownhouse limited to the “landed gentry,” but increasingly was open to the emerging middle class.During a time when John Locke’s theories regarding the virtues of the politically free individual— able to own land and live where he pleased— enjoyed renewed popularity, the new middleclass exercised their ability to build homes thatresponded to their needs and reflected their newstatus. The notion of the self-made man resulteda building type to serve it — the suburban singlefamily house.7Arguably the first suburbs were built by the newmiddle class outside of London, where 18th centurynotions regarding healthy, pastoral living, theprimacy of the family,8 and the house as symbolizing one’s social and economic status coalesced.What may have begun as weekend villas soontransitioned into primary residences to satisfye s ta b l i s h i n g t h e c o n tex t s15

new social and religious ideals. Women were nowpositioned as leading the domestic and spiritualaspects of the family, in a setting no longer compromised by the corrupting influences of thecity. The men, making use of improved roads andcarriages, commuted to the city, returning to theirideal “compact bourgeois villas”9 when their workwas done.The new suburban house of 18th century Englandnot only satisfied the changed social and familyneeds of the new middle class, but through itssetting and style appropriated images of powerof the county estates of the aristocracy. In otherwords, the houses they built symbolized thepolitical and monetary gains that this new classhad achieved. Early subdivisions even adoptedaristocratic names, such as Victoria Park in Manchester.10 And, essential to the validation of theirnew social status was separation from the “lowerclasses.” This was a gradual but significant change,as previously maintaining one’s social positiondepended only on title or peerage (as the classesfreely intermingled in cities such as London andManchester). Now it demanded the physical separation only the new suburbs could provide. Thus,an early model develops of residential enclaves,set in ex-urban settings where land was cheap,connected to work and commerce by new transportation technologies, all of which served to sati

Wake County, including overcrowded households and units without plumbing and/or heating. Pictured: Manufactured house in Holly Springs. Open country and farmland are part of what makes Wake County a beautiful and unique place. Unfortunately, the very qualities that make Wake County special risk becoming placeless sprawl.