Transcription

160 " [.AprilFLOCKINGBEHAVIORINBIRDSBY JOHN T. EMLEN, JR.MOVERN studies of social behavior in birds have concentratedontwo problems: 1) the mechanismsof integration of the organizedsocialunit, and 2) the effectsof the socialenvironmenton the activity,fecundity, and survival of the individual. The first of these has beenbrought to your attention by Dr. Collias in his discussionof the development of socialbehavior (Auk, 69: 127-159, 1952). The secondwilloccupy the attention of the two remaining papersin this symposium,thoseby Dr. Davis and Dr. Darling (Auk, 69: 171-191, 1952). In theinterimI wouldlike to bringup for yourconsiderationa third aspectof socialbehavior--that of flockingresponses,gregariousness,and thevarious factors which determine the size and density characteristicsof bird flocks.The actuality of flocking behavior in birds does not need to beproved. It is everywhere in evidence, indeed it is difficult to findsituations and specieswhich do not show at least a trace of it. Largeand dense bird flocks are familiarto the most casual observer.Chat-tering hordesof migrating blackbirds, swirling cloudsof swallowsin apre-roostingflight, jostling crowdsof sea-birdson a rocky islet; suchscenesprovide someof the most thrilling spectaclesto be seenin birdlife.The term flock, while commonlyassociatedwith such spectacularphenomena,will be applied in this discussionto any aggregationofhomogeneousindividuals, regardlessof size or density. The wordhomogeneousas used here is not to be interpreted in too strict amanner, but is employedin order to excludethe specialheterogeneousgroupingsof sex and age categoriesoccurringin the breedingpair andthe parent-young family group. A flock in this broad sensemightresult simply from a convergenceof independent individuals at acommon, localized sourceof attraction such as a patch of shade or afeeding station. It might, on the other hand, arise as a result of amutual attraction betweenindividuals. In many bird flocksit isprobable that both of these factors operate, the relative r5les of eachvarying with the speciesand with the circumstances.SOCIAL FoRcES IN BALANCEThe convergenceof birds in responseto external physical factorspresents,in itself, no great problemsto the student of bird behavior.Social responses,on the other hand, are highly complexand fraughtwith challengingproblems.

Vol. 69 1952J] MI,I N,FlockingBehaviorin Birds161The tendencyof birds to respondpositivelyto the presenceof othersof their kind, commonly referred to as gregariousness,is little understooddespiteits conspicuousnessand widespreadoccurrence. Variouswriters have comparedit with hunger, a craving or sensationof discomfortwhicharisesin the absenceof a physicalrequirement. Trotter(1916:30) describedgregariousnessas an impulsein individualsto bein and remain with the flock and to resist anything which tended toseparatethem from it. Craig (1918) classifiedit as an appetite,whichhe definedas "a state of agitation which continuessolong as a certainstimulus--is absent," and which is resolvedas soonas the appetedstimulusis received. Wheeler (1928:11) comparedit with the appetites of hungerand sexand notedits persistentnature and its strikingeffects on segregatedindividuals. Various psychologistshave regarded it as a condition of responsivenessto social stimuli which, ifblocked, leads to frustration activities.Illustrationsof gregariousbehaviorare not hard to find. Nearlyeveryone has watched stragglersfrom a flock of Starlings hurry tojoin their confreres,or has seenpassingCrows respondto a flock oftheir kind on the ground. Duck and goosehunters are thoroughlyfamiliar with the effect that a groupof decoyshas on their quarry.Alverdes(1927:108)notedhow the artificial isolationof a socialanimalsuchasa dogproducesnumeroussignsof discomfortwhilethe presenceof a companion,evenonebelongingto anotherspecies,will quiet these"socialcravings." Stresemann(1917) discussedthe fascinationwhicha flock of birds holdsfor a segregatedindividual.While few would deny this positive social reaction among themembersof a flock, Allee (1931) and others have pointed out thatthere is another factor operatingin the formation and regulationofaggregations, the factor of tolerance of social encroachment.Socialtolerancemay be consideredas promotingflockingbehaviorby permitting the membersof a populationto convergein responseto either environmental or internal (gregarious)factors. For ourpurposes,however,it is convenientto considertolerancein its negativeaspect as intolerance, an expressionof independenceor self-assertionacting in oppositionto forceswhich tend to bring birds togetherintoflocks. Socialintoleranceis functionallythe antithesisof gregariousness. If we follow Craig in callingthe cravingfor companionshipanappetite,this second,negativefactor is an "aversion,"a state of agitation whichcontinuessolongasa certainstimulusis presentbut whichceaseswhen that stimulusis withdrawn (Craig, 1918).This negativereactionof individualsto crowdingis of widespreadoccurrencein animal populationsof all kinds and needslittle elabora-

162tion.[AukSm, N,FlockingBehaviorinBirds[AprilIt is particularly conspicuousin birds and is nowhere betterillustratedthanin the territorialbehaviorof bothcolonialand non-colonial species. It underlies most of the situations which lead toconflictbetweenindividualsin natureand is consideredbasic in ourmodern conceptsof the mechanismsof population regulation. Problems of social tolerance and the r81e of aggressionin the integrationand regulation of bird flocks have recently been reviewed by Collias(1944).We thus have two opposingforces,a positive force of mutual attraction and a negativeforce of mutual repulsion,interacting in the formation of bird flocks. The positive force initiates the processand actscentripetally in drawing membership; the negative force serves aregulatory r81e, limiting the size of the flock and preventing dosecrowding through its centrifugal action. Such a concept may becriticized by those who, encounteringdifficulties in elucidating emotions in subhumansubjects,object to the word "force" as applied tobird behavior. In the present ease, however, I am not referring toany stored or penned-upenergy but simply to the causeof the centripetal or eentifugalmovementsobserved,whatever that might be (seeWebster's unabridged dictionary, 2nd edition, definition No. 15).The responsesmight be regardedas essentiallytropistieand comparable to the prototaxesproposedby Wallin (1927).No matter what terminology we choose, there seems little doubtthat positiveand negativesocialresponsesoccurand interact. Craigobservedthis interaction in the behavior of his caged Ring Doves asthey settled on their roostsfor the night. Each bird, he sayssoughta perch closeto friendly companions,but ,tot too close,and the difficulties involved in satisfying both the appetite for companionshipandthe aversionfor crowdingoften kept the birds busy for more than anhour. I have observedsimilar performancesin roostingcrowsand inloafing flocks of starlings and swallows. By way of illustration, Iwould like to relate some observations which I made on Cliff Swallows,Petrochelidonpyrrhonota,during the past summer.Cliff Swallowsnear a group of nestingcoloniesat Moran, Wyoming,spent much of their time loafingon spansof telephonewires. Positivesocial forces were immediately apparent in this behavior for the distribution of the birds over the available percheson the roostswas farfrom random.Of the thousandsof linear feet of wire to be found inthe area only a few relatively small sectionswere used at any one time.One or two birds, alighting apparently at random, typically served asthe nucleus for a potential gathering. Other birds followed until anaggregation of 100 or more had accumulated, all within a space of100 to 150 feet.

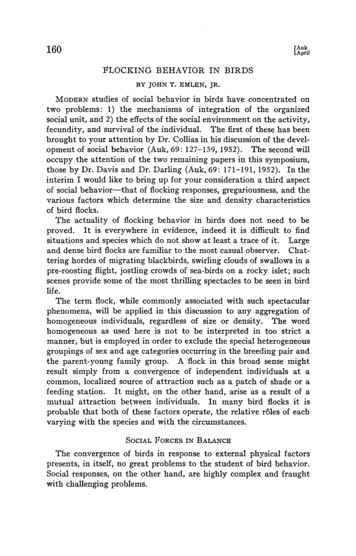

Vol.1952691JE xL N,FlockingBehaviorin Birds163Negative socialforceswere also apparent, for in spite of the overallcompactnessof the group no bird ever held a perch closerthan aboutfour inchesfrom its nearest neighbor. Birds were constantly arrivingand leaving, and an unstable situation occasionallyarose when a birdattem )ted to securea perch too closeto another, already-settledbird.32/oa 20o/ O oo øße "ß0' 0 I II IIII 8TI EIIII0II III III II,18IN INUTESFIOgR 1. Sample curve showingin.ease in numb of Cliff Swallowsp chingon the n al thkd (open ckcles), east tMrd (solid ckcl ), and west thkd (halfekcles) of a sectionof telephonewkes ne Moran, Wyoming, Au st 4, 1950.Shuffling and reshufflinginevitably followed until the proper spacinghad been reestablishedall down the line. Ten-inch gaps were filledcentrally and without trouble, a six-inchspaceon the o er hand wasusually avoided and, if chosen,was invaded only with the accompaniment of aggressivedisplays and a local reshufflingof perches. Swallows move theirfeet but littlewhen once settledand this tolerancelimit of four inchesmay be related to the maximum reach of a birdfrom a fixed perch.In an accumulating aggregation of this sort the een al portion ofthe perching area tended to fill more rapidly than did the peripheralportions,and shifts from peripheral to central positionsoeecred morefrequently than did shifts in the other direction. Thus when theperching area was optically divided by the observerinto three comparable sectionsand the number of birds in each of the sectionscountedat one minute intervals, the central section was seen to grow mostrapidly. If the processcontinued for some time, however, and thecentral section became filled to capacity, a change in the growthpiet e ensued and the een al section stabi zed or even dec,nedwhile the peripheralsectionsadvanced(Fig. 1).

164Observationssame narrow[AukE, N, FlockingBehaviorinBirdsof territorialbutdefinite[Alarildefense at the nests indicatetolerancelimitationsthatthatthewere seen in therestingflockson telephonewires applied. The spatial arrangementsof nests in the coloniesalso indicated that the proximity of nestopeningswas limited by the reachof a perchingswallow. Details oftheseobservationswill be publishedshortly in another paper (Emlen,in press,Condor, 1952).As I have already suggested,the size and density characteristicsofa bird flock are determined by the balance of centripetal and centrifugal forcesacting on an innate pattern of behavioral response.Without suchforceswe may assumethat the dispersalof the membersof a population over its range would be random. A positive socialforce acting alone on such a randomly distributed population wouldtend to produceclustersand might, if unchecked,lead to the completeaggregation of all individuals into one great and compact flock.Negative forces would presumablyintervene, however, to limit andregulate this processof aggregationand, in balance with the positiveforces, produce a pattern of small dispersedaggregationseach indynamicbalancewithin itself and with neighboringaggregations.Variations in the size and density characteristicsof flocks may beinterpreted as resultingfrom different balancesof these positive andnegativesocialforces. A few speciesunder certaincircumstancesmayexhibit the positive social attraction with very little of the negativeelement of intolerance. This apparently is the case in the sleepingdusters of tree swifts (Hemiprocnidae),wood swallows(Artamidae),and colies (Coliidae) (Allen, 1925:270; Pycraft, 1910:138). RoostingPassengerPigeonswere said by Kalm (1759) to pile up in heapsonthe branchesand by Audubon (1831:324) to form solid massesas largeas hogsheads. Other examplesof clusteringoccur,particularly amongspecieswhich roostin cavities,but a far more commonsituation is tofind the birds spacedand jealously defendingtheir immediate surroundingsevenin largeand denseflocks. Thus, swallowsspacethemselvesalongtelephonewiresand rarely if ever tolerate physicalcontactwith neighbors. Murres nest in densecoloniesyet vigorouslydefendtheir immediate surroundingsagainst others of their kind (Howard,1920:143). Roosting crows, despite early accounts of clustering(Godman, 1842; Wright, 1897:178), characteristically adjust and readjust their percheson the outer twigs of the roosting trees until asuitable interval of three or four inches is achieved (unpublishedpersonalobservationsmade in California and New York).Small flocks and flocks of low density may be regarded as representinga furthershiftin the balancethrougha reducedgregariousness,

Vol.5911952 .J MLI N,FlockingBehaviorin Birds165an increasedintolerance, or a combination of both. Even dispersedsocial groupingsand territorial societiesmay be included in this concept as casesin which negativeforcesare stronglydeveloped. Thusterritorial Red-wings, Agelaius phoeniceus,for all their pugnacity,showmany evidencesof a colonialsocialbond (Robert Nero, unpubl.notes). Indeed, as Mr. Darling showsin the concludingpaper of thissymposium,socialattraction may be an essentialelementof territorialdisplay in relatively dispersedpopulationsof non-colonialspecies.The effectsof non-social,physicalfactors of the environmentsuchas a localizedcenter of attraction or a localizedsourceof repulsionmaybe superimposedon the pattern of dispersalset by the balance ofsocialforces. When suchfactorsare presentaggregationsmay developwhich violate the limits of socialintolerance and precipitate fightingwithin the flock. Fighting, for instance,is commonat winter feedingstationsamong specieswhich rarely quarrel back in the brush wherefood is more generally dispersed.Artificial confinement or other restrictions to free movement mayhave a similar effect. Fighting is frequent when birds are placedtogether in cages, and this is particularly noticeable among nonflockingspecies(Tompkins, 1933). It is alsoprevalent in very densebreeding populationsof territorial birds where crowdingcreatestheequivalentof spatial restriction(Palmer, 1941:100;Kendeigh,1941:42). The increasein aggressivenesswhich accompaniesthe springrecrudescenceof sexualactivity in flocksof California Quail (Sumner,1935:214)may perhapsreflecta temporaryviolation of socialtoleranceresulting from the inertia of the population in adjusting to internalchangesin sociality.With a fluctuating environment such as is encounteredin northernand temperatelatitudes and a fluctuating physiologysuchas is characteristic of nearly all birds, the balance of factors determiningflockingbehavior is obviouslyfar from stable.THE PHYSIOLOGY OF FLOCKINGHaving noted the existenceof centripetal forces related to socialattraction and of centrifugalforcesrelated to socialrepulsionoperatingin dynamic balancein bird flocks,it might be profitableto give briefattention to the physiologicalbasisof flocking responses.Since several forms of social behavior, such as those exhibited in thepairingrelationshipor in the parent-offspringrelationship,are demonstrably stimulatedand regulatedby specifichormones,oneis temptedto search for a hormonal basis for the definite and emotionally expressedsocial responses. No hormone for gregariousnesshas been

166 ,[AukFlockingBehaviorinBirds[Aprildemonstrated, however. The emotional aspects of social behaviorare probably related to nervoustensionsarisingas a result of frustratedattempts to follow a stereotypedneural pattern of social responsiveness.Socialintolerance,the disruptiveelementin flockingbehavior,is, bycontrast, often clearly related to the activity of specific hormones.Male sex hormoneshave been repeatedly shown to induce birds tofight with their flock associates,apparently as a part of the adjustmentfor sexual activity. Injections of a male hormone into free livingCalifornia Quail in winter producedaggressivedisplaysand, within afew days, withdrawal from the flock (Emlen and Lorenz, 1942).Castration, conversely,suppressedaggressivenessand fighting in malepigeons(Carpenter, 1932:522). Such responsesin experimentalbirdssuggest that the natural increase in sex hormone secretion by thegonadsin spring is directly related to the disintegration of winteringflocks in many species.Other hormonesmay influencegeneral aggressivenessunder specialconditions. Prolactin inducesmaternal reactions (Riddle, 1935), ciates.Thyroxin has little effect on domestichensexceptat high levelswhenit decreasesaggressiveness(Allee,Collias,and Beeman,1940). Estradiol producessimilar effectsin hens at high levels (Allee and Collias,1940).It thus appears that flocking responseshave their physiologicalbasis in stereotyped neural patterns and are influenced by hormonalfactors only as these incite disruptive responsesassociatedwith sexualor parental activity. The aggregated pattern of distribution, refleeting the unrestrictedaction of positive socialresponsesof gregariousnessmay thus be regarded as the neutral or "resting" state, andany deviation from it toward a dispersedpattern, a state of tensioneffected by the introduction of negative social elements.] NVIRONMENTAL i ACTORSThe fluctuations in sociality which are characteristicof most if notall speciesof birds correlate with two great rhythms of the environment, the seasonal and the diurnal.In both of these the factorswhich are associated with increased flocking are those that may beconsideredunfavorable. This correlation of aggregative tendencieswith unfavorable conditions has been noted and emphasized byAlverdes (1927) and various other writers concernedwith a widevariety of organisms, both vertebrate and invertebrate. Such

VoL 69]1952I] MLI Ig,FlockingBehaviorin Birds16r generalizationsshould be extended with caution, however, for theymay tend to hide the true relationships.Seasonal factors fluctuate at a slower tempo than diurnal factors,and their effectsmay thus becomeintegrated with the slowerforms ofresponsemechanismsin the bird's physiology, such as those whichinvolve conspicuousmorphologicalchangesof the primary, secondary,and accessorysexual structures. Diurnal factors, on the other hand,fluctuate at a tempo which precludes major morphological adjustments, and behavioral fluctuations associated with them are moresuperficial.Two factors associatedwith the seasonalcycle which commonlypromote flocking are low temperature and low precipitation. Thesecorrelations may be seen in the normal seasonalactivity cycles ofmany birds but are best illustrated, freed from the possibleeffects ofinnate rhythms, in the behavioral responsesof local populations toirregular fluctuations of weather.Although the spring recrudescenceof sexual activity with itscorollary aggressivenessis basically a physiologicalresponseto increased day-length, cold temperatures have a profound modifyinginfluence. Red-winged Blackbirds, for instance, respond to a coldspell during early stages of the nesting cycle by abandoning theiraggressivelydefended territories and returning to a winter flockingbehavior (Beer and Tibbitts, 1950:63). Many other speciesbehavesimilarly. Flocking should not be regarded as a general responsetocold, however, for in those specieswhich habitually breed in flocks,the effect of cold may be quite different. Thus Cliff Swallowsinseveral coloniesnear Moran, Wyoming, in 1950 respondedto an unseasonablecold spell early in the nesting season by temporarilyabandoning their half-built nests and shifting for two days from onetype of flocking behavior at the nesting site to another, slightly moredispersedtype on foraging grounds several miles away (Emlen,in press,Condor, 1952).Drought is another environmental factor which, occurring abnormally, may promoteflockingresponsesduring the non-flockingseason.This has been noted in Gambel Quail, Lophortyxgambelii, in aridportionsof southernCalifornia and Arizona where a failure of the usualspring rains inhibits the normal spring dispersalof the winter coveys(Leopold,1936:28). Endocrinedisturbancesresultingfrom nutritionaldeficienciesare thoughtto be responsible(MacGregorand Inlay, 1951).It thus appearsthat the behavioral responsesof birds to unseasonable coldor droughtconstituteessentiallya return to the non-breedingpattern of the species. This impliesa suppressionof sexualactivity

168EMI,EN,FlockingBehaviorinBirds[Auk[Apriland suggestsa reductioneither of hormoneoutput or of responsivenessto persisting levels of hormone in the blood. Regardlessof themechanisms, however, we may conclude that unfavorable weatherpromotesflockingbehavior by suppressingthe disruptive element ofsocial intolerance. There is no evidence that it directly modifiesgregariousnessitself.Light intensity is the principal environmentalvariable of the diurnalcycle,and it is quite evident throughobservationsof roostingbehaviorthat darknessis associatedwith increasedflocking in a great manyspecies. One has only to recall the great roostingassemblagesof suchdiverse birds as herons, gulls, vultures, ,and robinsto capture a realizationof thisresponseto the light cycle.Such sudden fluctuations in sociality are probably not associatedwith hormonal changessuch as those involved in the seasonalcycle;at least no suchrelationshipshave beendemonstrated. Perhapstheycan best be explained by relating them to the schedule of generalactivity imposedon the birds by alternating periodsof light and dark.Night is a period of enforcedinactivity for most birds, while the hoursof daylight provide the only time during which foraging and otheressential activities of self-maintenance can be performed. Selfmaintenancecalls for independentaction which, while not necessarilyinvolving socialintolerance,entails a certain amount of freedom frominterference. Thus, the membersof a coveyof quail disperseslightlyfrom their compactroostingaggregationduring the morningforagingperiod, may reunite to loaf during the noon hours, and then fan outagain for a secondfeeding period before finally congregatingfor thenight. The spectacularflights of blackbirdsto and from their hugeroostingassemblagesreflect the samealternation of periodsof activityand rest in a pattern and on a scale compatible with their specialfeedinghabits and greater mobility. The limited acreageof a blackbird roosting-site could not conceivably support, even briefly, thehundredsof thousandsof birds which congregateon it nightly.Thus, after foragingin a relatively dispersedpattern, and in a relatively independentmanner during the day, the membersof a population are temporarily releasedfrom the demands of self-maintenanceand are permitted to respondfreely to their basicgregariousappetites.RESUi AND CONCLUSIONSymposia such as the present one provide perhaps a legitimateexcusefor a little speculation. I hope that I have not abused thisprivilegeand steppedtoo far beyondthe firm shoreof establishedfacts.

Vol.1952 59'IIEm, , FlockingBehaviorin Birds160My objective has been to develop a theoretical basisfor interpretingflocking behavior and the various factors, both internal and external,which affect it. For. this I have proposedthat the form and densitycharacteristicsof bird flocksare determinedby the interplay of positive and negative forcesassociatedwith gregariousnesson the one handand intolerance and independenceon the other. Gregariousnesshasits basis in stereotyped neural patterns, and there is no evidence atpresent that it is affected directly by hormonal or environmentalinfluences. Social intolerance and independence,on the other hand,are highly variable, and in their variations regulate and determine thedispersalor flocking pattern of the population. Flocking reachesitshighest development when gregariousnessis given free rein, unrestricted by conflictingdemandsof reproductionand self-maintenance.Llg RAgUI CITEDA ,W.C.l 31. Animal ag egations, a study in general sociology. (Univ.Chicago Press, Chicago), pp. ix 431.A ,W. C., A N. Co AS.1 40. The influence of estradiol on the socialorganizationof flocksof hens. ndo inology, 27:g7- 4.A ,W. C., N. . Co AS, A E. B S.l .The effect of th oxin onthe socialord in flocksof hens. ndo inolo ,27:g27-g35.A s,G.M.1 25. Birds d their attributes. (Marshall ones Co., Boston),pp. xiii 338.A s,F. 1927. Social life in the animal world. (Transl. by K. C. Creasy).(Hareo t, Brace, New York), pp. ix 216.AuduboN, J. J. 1831. Ornithological bio aphy.(Dobson & Porter, Philaddphia), pp. xxiv 512.B ,J., a D. TmmYYs. 1950. Nesting beha or of the Red-wing Blaekbkd.Flicker, 22:61-77.Ca NY ,C.R.1932. Relation of the male a an gonad to responsespertinentto reproductive phenomena. Physiol. Bull., 29:509-527.COLLIaS, N.1944. Ag essive b a oramong v tebrateanimals. Ph iol.Zool., 17:83-123.C aIO, W.1918. Appetites and av sions as constituents of instincts. Biol.Bull., 34:91-107.E N,J. T., a F. W. Lo Nz.1942. Paking responsesof free-living Valley uail to sex-hormonepellet implants. Auk, 59:369-378.Oo a ,J. D. 1842. Ampican nat al history, Vol. II. (H. rey & I. Lea,Phila.), pp. 337.Howa ,H. E. 1920. T ritory in bkd life. (John M ay,London), pp. ii 308. L ,P. 1759. Bes ifning pl de vilda Dufvor, som somliga ir i sl otrolig stormyckenhet komma til de s6 a Engelska nybyggen i No a Am ica. Kongl.Vetenskaps-Akad. Handl. f6r ar 1759, 20:275-295 (transl. Oronb g , Auk,28: 53, 1911).K io ,S.C.1941. T itori and mating behavior of the honse en.IlLBiol. Monog., 18: 1-120.

170 LEN,FlockingBehaviorinBirds[Auk[AprilLEOPOLD,A. 1936. Game management. (Scribner's,New York), pp. xxi d- 481.MACG OR, W., ANDM. INLAY. 1951. Observationson failure of Gambel Quailto breed. Calif. Fish and Game, 37: 218-219.PAL ER, R.S.1941. A behavior study of the common tern.Proc. Bost. Soc.Nat. Hist., 42: 1-119.PYcl I T, W.P.1910. A history of birds. (Methuen & Co., London), pp. xxxi458.RmD E, O.1935. Aspects and implications of the hormonal control of the maternalinstinct. Proc. Amer. Philos. Soc., 75(6): 521-525.ST sE A ,E.1917. ber gemischteVogelschwiirme.Verh. der Ornith.Ges.in Bayern, 13(2): 127-151.Su E ,E. L., J .1935. A life history study of the California Quail with recom-mendations for its conservation and management.Calif. Fish and Game, 21:167-256.TO PKINS, G.1933. Individuality and territoriality as displayedin winter bythree passefine species. Condor, 35.' 98-106.T OTTE , W .1916. Instincts of the herd in peaceand war. (T. Fisher, Unwin.Ltd., London), pp. 213.WALLIN, I.E.1927. Symbionticismand the origin of species. (Williams andWilkins, Baltimore), pp. xi 171.Wm ELER,W.M.1928. The socialinsects,their origin and evolution. (HarcourtBrace, New York), pp. xviii 378.W Io ,J.S.1897. Notes on crow roosts of western Indiana and eastern Illinois.Proc. Ind. Acad. Sci., 1897: 178-180.Departmentof Zoology, Universityof Wisconsin,Madison, Wisconsin,November 28, 1951.

brought to your attention by Dr. Collias in his discussion of the devel- opment of social behavior (Auk, 69: 127-159, 1952). The second will occupy the attention of the two remaining papers in this symposium, those by Dr. Davis and Dr. Darling (Auk, 69: 171-191, 1952). In the interim I would like to bring up for your consideration a third aspect